Ear, Nose, and Throat Disorders

INTRODUCTION

Ear, nose, and throat disorders rarely prove fatal (except for those resulting from neoplasms, epiglottitis, and neck trauma), but they may cause serious social, cosmetic, and communication problems. Untreated hearing loss or deafness can drastically impair ability to interact with society. Ear disorders also can cause impaired equilibrium. Nasal disorders can cause changes in facial features and interfere with breathing and tasting. Diseases arising in the throat may threaten airway patency and interfere with speech. In addition, these disorders can cause considerable discomfort and pain for the patient and require thorough assessment and prompt treatment.

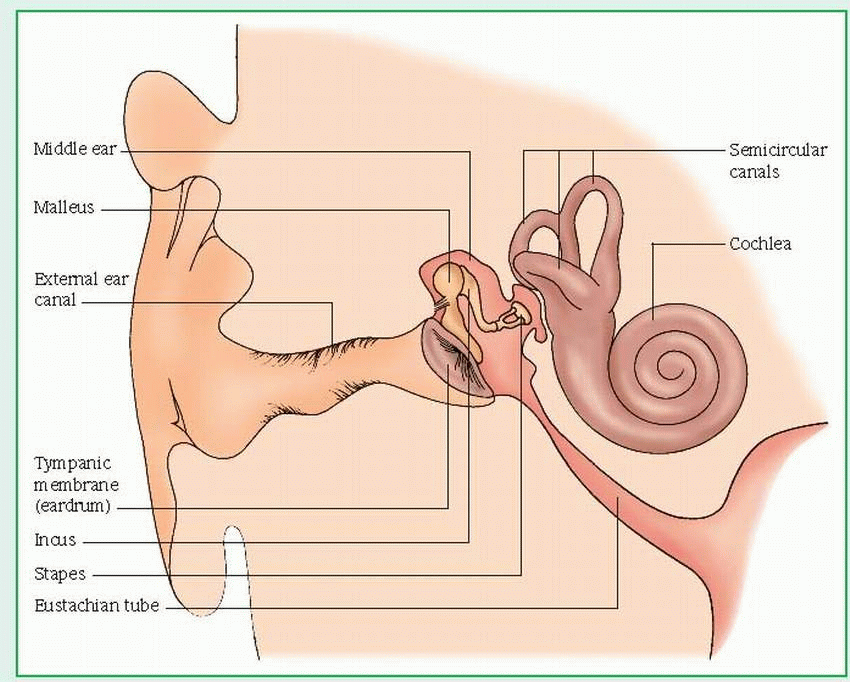

THE EAR

Hearing begins when sound waves reach the tympanic membrane, which then vibrates the ossicles, incus, malleus, and stapes in the middle ear cavity. The stapes transmits these vibrations to the perilymphatic fluid in the inner ear by vibrating against the oval window. The vibrations then pass across the cochlea’s fluid receptor cells in the basilar membrane, stimulating movement of the hair cells of the organ of Corti. The axons of the cochlear nerve terminate around the bases of those hair cells. Sound waves, which initiate impulses, travel over the auditory nerve (made up of the cochlear nerve and the vestibular nerve) to the temporal lobe of the brain.

The inner ear structures also maintain the body’s equilibrium and balance through the fluid in the semicircular canals. This fluid is set in motion by body movement and stimulates nerve cells that line the canals. These cells, in turn, transmit impulses to the cerebellum of the brain by way of the vestibular branch of the eighth cranial nerve (the acoustic nerve).

Although the ear can respond to sounds that vibrate at frequencies from 20 to 20,000 hertz (Hz), the range of normal speech is from 250 to 4,000 Hz, with 70% falling between 500 and 2,000 Hz. The ratio between sound intensities, the decibel (dB) is the unit for expressing the relative intensity (loudness) of sounds. A faint whisper registers 10 to 15 dB; average conversation, 50 to 60 dB; a shout, 85 to 90 dB. Hearing damage may follow exposure to sounds louder than 90 dB.

ASSESSMENT

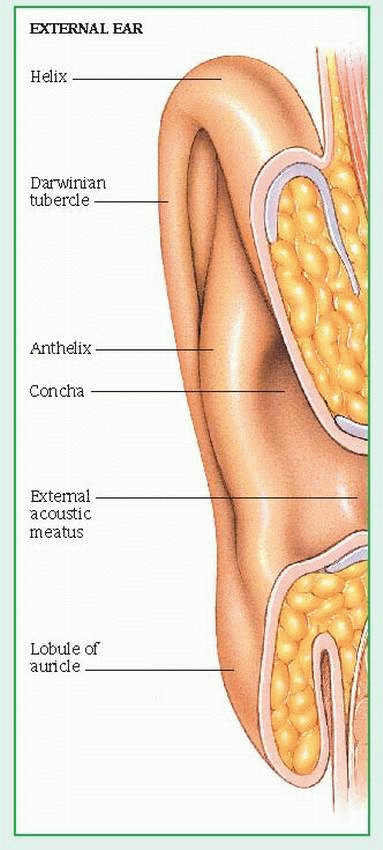

After obtaining a thorough patient history of ear disease, inspect the auricle and surrounding tissue for deformities, lumps, and skin lesions. (See Structures of the external ear.) Ask the patient if he has ear pain. If you see inflammation, check for tenderness by moving the auricle and pressing on the tragus and the mastoid process. Check the ear canal for excessive cerumen, discharge, or foreign bodies.

Ask the patient if he has had episodes of vertigo or blurred vision. To test for vertigo, have the patient stand on one foot and close his eyes, or have him walk a straight line with his eyes closed. Ask him if he always falls to the same side and if the room seems to be spinning.

AUDIOMETRIC TESTING

Audiometric testing evaluates hearing and determines the type and extent of hearing loss. The simplest but least reliable method for judging hearing acuity consists of covering one of the patient’s ears, standing 18″ to 24″ (46 to 61 cm) from the uncovered ear, and whispering a short phrase or series of numbers. (Block the patient’s vision to prevent lip reading.) Then ask the patient to repeat the phrase or series of numbers. To test hearing at both high and low frequencies, repeat the test in a normal speaking voice. (As an alternative, you can hold a ticking watch to the patient’s ear.)

If you identify a hearing loss, further testing is necessary to determine if the loss is conductive or sensorineural. A conductive loss can result from faulty bone conduction (inability of the eighth cranial nerve to respond to sound waves traveling through the skull) or faulty air conduction (impaired transmission of sound through ear structures to the auditory nerve and, ultimately, the temporal lobe of the brain).

Sensorineural hearing loss results from damage to the cochlear or vestibulocochlear nerve, which can result from aging and prolonged exposure to high-frequency or loud noises.

The following tests assess bone and air conduction:

Impedance audiometry detects middle ear pathology, precisely determining the degree of tympanic membrane and middle ear mobility. One end of the impedance audiometer, a probe with three small tubes, is inserted into the external canal; the other end is attached to an oscillator. One tube delivers a low tone of variable intensity, the second contains a microphone, and the third, an air pump. A mobile tympanic membrane reflects minimal sound waves and produces a low-voltage curve on the graph. A tympanic membrane with decreased mobility reflects maximal sound waves and produces a high-voltage curve.

Pure tone audiometry uses an audiometer to produce a series of pure tones of calibrated decibels (dB) of loudness at different frequencies (125 to 8,000 Hz). These test tones are conveyed to the patient’s ears through headphones or a bone conduction (sound) vibrator. Speech threshold represents the loudness at which a person with normal hearing can perceive the tone. Both air conduction and bone conduction are measured for each ear, and the results are plotted on a graph. If hearing is normal, the line is plotted at 0 dB. In adults, normal hearing may range from 0 to 25 dB.

In the Rinne test, the base of a lightly vibrating tuning fork is placed on the mastoid process (bone conduction). Then the fork is moved to the front of the meatus, where the patient should continue to hear the vibrations (air conduction). The patient must determine which sounds are heard longer. In a positive Rinne test, sounds heard through air conduction are heard relatively longer than those heard through bone conduction. This may suggest sensorineural hearing loss. In a negative Rinne test, sounds heard through bone conduction are heard longer than those heard through air conduction, which may suggest a conductive loss.

Speech audiometry uses the same technique as pure tone audiometry, but with speech, instead of pure tones, transmitted through the headset. (A person with normal hearing can hear and repeat 88% to 100% of transmitted words.)

Tympanometry, using the impedance audiometer, measures tympanic membrane compliance with air pressure variations in the external canal and determines the degree of negative pressure in the middle ear.

In Weber’s test (used for testing unilateral hearing loss), the handle of a lightly vibrating tuning fork is placed on the midline of the forehead. Normally, the patient should hear sounds equally in both ears. With conductive hearing loss, sound lateralizes (localizes) to the ear with the poorest hearing. With sensorineural loss, sound lateralizes to the better functioning ear.

THE NOSE

As air travels between the septum and the turbinates, it touches sensory hairs (cilia) in the mucosal surface, which then add, retain, or remove moisture and particles in the air to ensure delivery of humid, bacteria-free air to the pharynx and lungs. In addition, when air touches the mucosal cilia, the resultant stimulation of the first cranial nerve sends nerve impulses to the olfactory area of the frontal cortex, providing the sense of smell.

ASSESSMENT

Check the external nose for redness, edema, masses, or poor alignment. Marked septal cartilage depression may indicate saddle deformity due to septal destruction from trauma or congenital syphilis; extreme lateral deviation may result from injury. Red nostrils may indicate frequent nose blowing caused by allergies or infectious rhinitis. Dilated, engorged blood vessels may suggest alcoholism or constant exposure to the elements. A bulbous, discolored nose may be a sign of rosacea.

With a nasal speculum and adequate lighting, check nasal mucosa for pallor and edema or redness and inflammation, dried mucous plugs, furuncles, and polyps. Also, look for abnormal appearance of the capillaries, boggy turbinates, and a deviated or perforated septum. Check for nasal discharge (assess color, consistency, and odor) and blood. Profuse, thin, watery discharge may indicate allergy or cold; excessive, thin, purulent discharge may indicate cold or chronic sinus infection.

Check for sinus inflammation by applying pressure to the nostrils, orbital rims, and cheeks. Pain after pressure applied above the upper orbital rims indicates frontal sinus irritation; pain after pressure applied to the cheeks, maxillary sinus irritation.

THE THROAT

Parts of the throat include the pharynx, epiglottis, and larynx. The pharynx is the passageway for food to the esophagus and air to the larynx. The epiglottis (the lid of the larynx) diverts material away from the glottis during swallowing. The larynx produces sounds by vibrating expired air through the vocal cords. Changes in vocal cord length and air pressure affect pitch and voice intensity. The larynx also stimulates the vital cough reflex when a foreign body touches its sensitive mucosa.

ASSESSMENT

Using a bright light and a tongue blade, inspect the patient’s mouth and throat. Look for inflammation or white patches, and any irregularities on the tongue or throat. Make sure the patient’s airway isn’t compromised and also assess vital signs. Watch for and immediately report signs of respiratory distress (dyspnea, tachycardia, tachypnea, inspiratory stridor, restlessness, and nasal flaring) and changes in voice or in skin color, such as circumoral or nail bed cyanosis. Assess symmetry of the tongue as well as function of the soft palate. The main diagnostic test used in throat assessment is a culture to identify the infective organism.

EXTERNAL EAR

Otitis externa

Otitis externa, inflammation of the skin of the external ear canal and auricle, may be acute or chronic. Also known as external otitis and swimmer’s ear, it’s most common in the summer. With treatment, acute otitis externa usually subsides within 7 days—although it may become chronic—and tends to recur.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Otitis externa usually results from bacteria, such as Pseudomonas, Proteus vulgaris, Staphylococcus aureus, and streptococci and, sometimes, from fungi, such as Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans (fungal otitis externa is most common in tropical regions). Occasionally, chronic otitis externa results from dermatologic conditions, such as seborrhea or psoriasis. Allergic reactions stemming from nickel or chromium earrings, chemicals in hair spray, cosmetics, hearing aids, and medications (such as sulfonamide and neomycin, which is commonly used to treat otitis externa) can also cause otitis externa.

Predisposing factors include:

swimming in contaminated water (Cerumen creates a culture medium for the waterborne organism.)

cleaning the ear canal with a cotton swab, bobby pin, finger, or other foreign object (This irritates the ear canal and, possibly, introduces the infecting microorganism.)

exposure to dust or hair-care products (such as hair spray or other irritants), which causes the patient to scratch his ear, excoriating the auricle and canal

regular use of earphones, earplugs, or earmuffs, which trap moisture in the ear canal, creating a culture medium for infection (especially if earplugs don’t fit properly)

chronic drainage from a perforated tympanic membrane

perfumes or self-administered eardrops

COMPLICATIONS

Complete closure of the ear canal

Significant hearing loss

Otitis media

Cellulitis

Abscesses

Stenosis

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

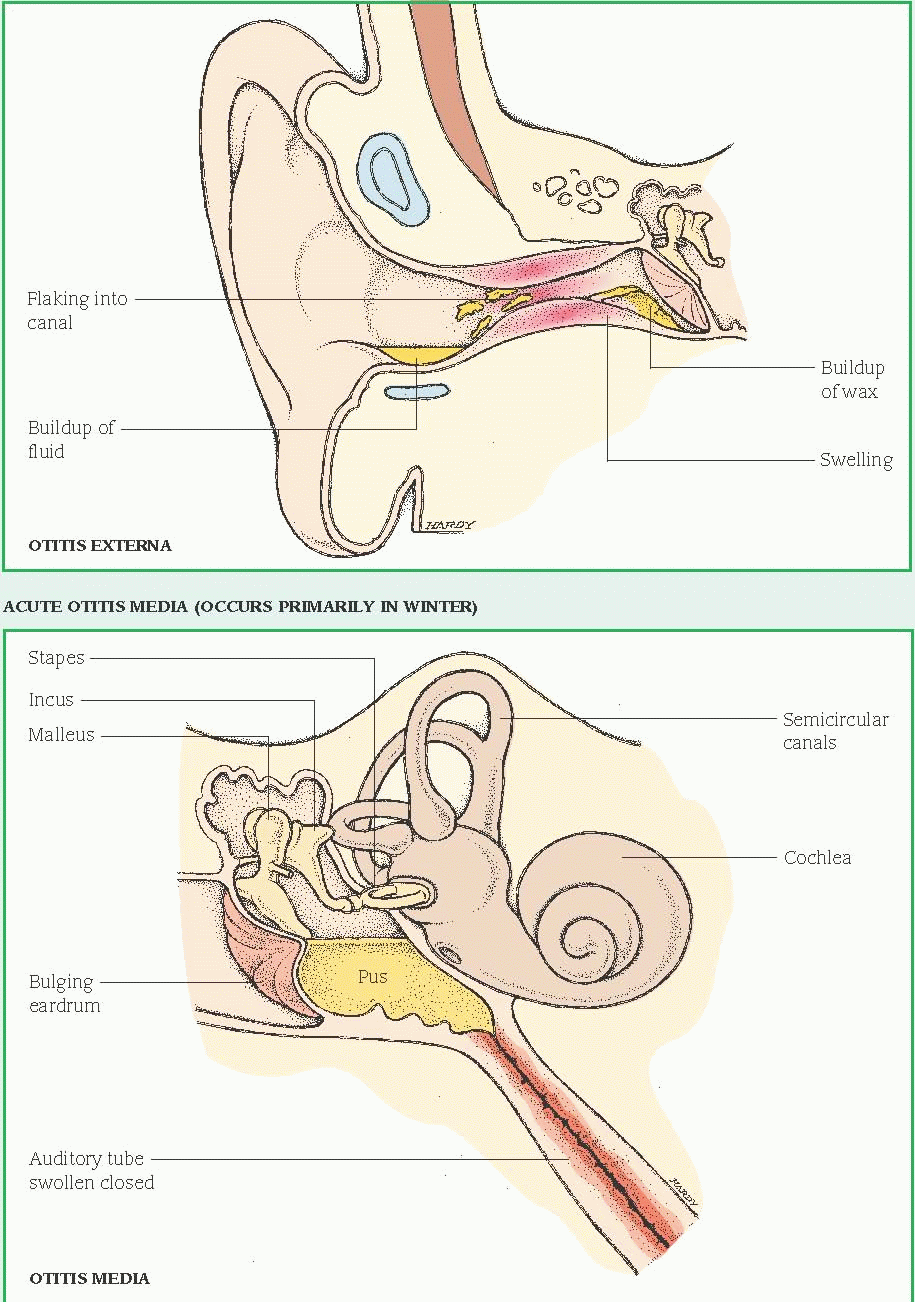

Acute otitis externa characteristically produces moderate to severe pain that’s exacerbated by manipulating the auricle or tragus, clenching the teeth, opening the mouth, or chewing. Its other clinical effects may include fever, foulsmelling discharge, crusting in the external ear, regional cellulitis, partial hearing loss, and itching. It’s usually difficult to view the tympanic

membrane because of pain in the external canal. Hearing acuity is normal unless complete occlusion has occurred.

membrane because of pain in the external canal. Hearing acuity is normal unless complete occlusion has occurred.

Fungal otitis externa may be asymptomatic, although A. niger produces a black or gray, blotting, paperlike growth in the ear canal. In chronic otitis externa, pruritus replaces pain, and scratching may lead to scaling and skin thickening. Aural discharge may also occur.

DIAGNOSIS

Physical examination confirms otitis externa. In acute otitis externa, otoscopy reveals a swollen external ear canal (sometimes to the point of complete closure), periauricular lymphadenopathy (tender nodes anterior to the tragus, posterior to the ear, or in the upper neck) and, occasionally, regional cellulitis.

In fungal otitis externa, removal of the growth reveals thick red epithelium. Microscopic examination or culture and sensitivity tests can identify the causative organism and determine antibiotic treatment. Pain on palpation of the tragus or auricle distinguishes acute otitis externa from acute otitis media. (See Differentiating acute otitis externa from acute otitis media, page 632.)

In chronic otitis externa, physical examination reveals thick red epithelium in the ear canal. Severe chronic otitis externa may reflect underlying diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, or nephritis. Microscopic examination or culture and sensitivity tests can identify the causative organism and help in the determination of antibiotic treatment.

TREATMENT

To relieve the pain of acute otitis externa, treatment includes heat therapy to the periauricular region (heat lamp; hot, damp compresses; or a heating pad), aspirin or acetaminophen, and codeine. Instillation of antibiotic eardrops (with or without hydrocortisone) follows cleaning of the ear and removal of debris. However, a corticosteroid helps reduce the inflammatory response. If fever persists or regional cellulitis or tender postauricular adenopathy develops, a systemic antibiotic is necessary.

If the ear canal is too edematous for the instillation of eardrops, an ear wick may be used for the first few days.

Topical treatment is generally required for otitis externa, as systemic antibiotics alone aren’t sufficient. Analgesics, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, may be required temporarily.

As with other forms of this disorder, fungal otitis externa necessitates careful cleaning of the ear. Application of a keratolytic or 2% salicylic acid in cream containing nystatin may help treat otitis externa resulting from candidal organisms. Instillation of slightly acidic eardrops creates an unfavorable environment in the ear canal for most fungi as well as Pseudomonas. No specific treatment exists for otitis externa caused by A. niger, except repeated cleaning of the ear canal with baby oil.

In chronic otitis externa, primary treatment consists of cleaning the ear and removing debris. Supplemental therapy includes instillation of antibiotic eardrops or application of antibiotic ointment or cream (neomycin, bacitracin, or polymyxin B, possibly combined with hydrocortisone). Another ointment contains phenol, salicylic acid, precipitated sulfur, and petroleum jelly and produces exfoliative and antipruritic effects.

For mild chronic otitis externa, treatment may include instillation of antibiotic eardrops once or twice weekly and wearing of specially fitted earplugs while the patient is showering, shampooing, or swimming.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

If the patient has acute otitis externa:

The patient shouldn’t participate in any swimming activity.

Have the patient return to the clinic in 1 week for evaluation of the tympanic membrane to make sure it’s intact.

Monitor vital signs, particularly temperature. Watch for and record the type and amount of aural drainage.

Remove debris and gently clean the ear canal with mild Burow’s solution (aluminum acetate). Place a wisp of cotton soaked with solution into the ear, and apply a saturated compress directly to the auricle. Afterward, dry the ear gently but thoroughly. (In severe otitis externa, such cleaning may be delayed until after initial treatment with antibiotic eardrops.)

To instill eardrops in an adult, grasp the helix and pull upward and backward to straighten the canal.

To instill eardrops in a child, pull the earlobe downward and backward. To ensure that the drops reach the epithelium, insert a wisp of cotton moistened with eardrops.

Tell the patient to notify the physician if he develops an allergic reaction to the antibiotic drops or ointment, which may be indicated by increased swelling and discomfort of the area and worsening of other symptoms.

If the patient has chronic otitis externa, clean the ear thoroughly. Use wet soaks intermittently

on oozing or infected skin. If the patient has a chronic fungal infection, clean the ear canal well, then apply an exfoliative ointment.

on oozing or infected skin. If the patient has a chronic fungal infection, clean the ear canal well, then apply an exfoliative ointment.

Any patient who has experienced otitis externa should be taught to prevent a recurrence by avoiding irritants, such as hair-care products and earrings, and by avoiding cleaning the ears with cotton-tipped applicators or other objects. Encourage him to keep water out of his ears when showering or shampooing by using lamb’s wool earplugs, coated with petroleum jelly. Also, parents of young children should be told that modeling clay makes a tight seal to prevent water from getting into the external ear canal.

In addition, when the patient goes swimming he should keep his head above water or wear earplugs. After swimming, he should instill one or two drops of a mixture that is onehalf 70% alcohol and one-half white vinegar to toughen the skin of the external ear canal.

Urge prompt treatment for otitis media to prevent perforation of the tympanic membrane. (See Preventing otitis externa.)

If the patient is an elderly person or has diabetes, evaluate him for malignant otitis externa.

Children who have an intact tympanic membrane but are predisposed to otitis externa from swimming should instill two to three drops of a 1:1 solution of white vinegar and 70% ethyl alcohol into their ears before and after swimming.

Benign tumors of the ear canal

Benign tumors may develop anywhere in the ear canal. Common types include keloids, osteomas, and sebaceous cysts; their causes vary. (See Causes and characteristics of benign ear tumors, page 634.) These tumors seldom become malignant; with proper treatment, the prognosis is excellent.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

A benign ear tumor is usually asymptomatic, unless it becomes infected, in which case pain, fever, or inflammation may result. (Pain is usually a sign of a malignant tumor.) If the tumor grows large enough to obstruct the ear canal by itself or through accumulated cerumen and debris, it may cause hearing loss and the sensation of pressure.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical features and patient history suggest a benign tumor of the ear canal; otoscopy confirms it. To rule out cancer, a biopsy may be necessary.

TREATMENT

Generally, a benign tumor requires surgical excision if it obstructs the ear canal, is cosmetically undesirable, or becomes malignant.

Treatment for keloids may include surgery followed by repeated injections of long-acting steroids into the suture line. Excision must be complete, but even this may not prevent recurrence.

Surgical excision of an osteoma consists of elevating the skin from the surface of the bony growth and shaving the osteoma with a mechanical burr or drill.

Before surgery, a sebaceous cyst requires preliminary treatment with antibiotics, to reduce inflammation. To prevent recurrence, excision must be complete, including the sac or capsule of the cyst.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Because treatment for benign ear tumors generally doesn’t require hospitalization, focus care on emotional support and on providing appropriate patient education so that the patient follows his therapeutic plan properly when he’s at home.

Thoroughly explain diagnostic procedures and treatment to the patient and his family. Reassure them and answer any questions they may have.

After surgery, instruct the patient in good aural hygiene. Until his ear is completely healed, advise him not to insert anything into his ear or allow water to get into it. Suggest that he cover his ears with a cap when showering.

Teach the patient how to recognize signs of infection, such as pain, fever, localized redness, and swelling. If he detects any of these signs, instruct him to report them immediately.

Tumor | Causes and incidence | Characteristics |

Keloid | ▪ Surgery or trauma such as ear piercing ▪ Most common in blacks | ▪ Hypertrophy and fibrosis of scar tissue ▪ Commonly recurs |

Osteoma | ▪ Idiopathic growth ▪ Predisposing factor: swimming in cold water ▪ Three times more common in males than in females ▪ Seldom occurs before adolescence | ▪ Bony outgrowth from wall of external auditory meatus ▪ Usually bilateral and multiple (exostoses) ▪ May be circumscribed or diffuse, nondisplaceable, nontender |

Sebaceous cyst | ▪ Obstruction of a sebaceous gland | ▪ Painless, circumscribed, round mass of variable size filled with oily, fatty, glandular secretions ▪ May occur on external ear and outer third of external auditory canal |

MIDDLE EAR

Otitis media

Otitis media, inflammation of the middle ear, may be suppurative or secretory, acute, persistent, unresponsive, or chronic. With prompt treatment, the prognosis for acute otitis media is excellent; however, prolonged accumulation of fluid within the middle ear cavity causes chronic otitis media and, possibly, perforation of the tympanic membrane. (See Site of otitis media, page 635.)

Chronic suppurative otitis media may lead to scarring, adhesions, and severe structural or functional ear damage. Chronic secretory otitis media, with its persistent inflammation and pressure, may cause conductive hearing loss.

Recurrent otitis media is defined as three nearacute otitis media episodes within 6 months or four episodes of acute otitis media within 1 year.

Otitis media with complications involves damage to middle ear structures (such as adhesions, retraction, pockets, cholesteatoma, and intratemporal and intracranial complications).

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Otitis media results from disruption of eustachian tube patency. In the suppurative form, respiratory tract infection, allergic reaction, nasotracheal intubation, or positional changes allow nasopharyngeal flora to reflux through the eustachian tube and colonize the middle ear. Suppurative otitis media usually results from bacterial infection with pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae (the most common cause in children younger than age 6), Moraxella catarrhalis, beta-hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci (most common cause in children age 6 or older), or gram-negative bacteria. Predisposing factors include the normally wider, shorter, more horizontal eustachian tubes and increased lymphoid tissue in children, as well as anatomic anomalies. Chronic suppurative otitis media results from inadequate treatment for acute otitis episodes or from infection by resistant strains of bacteria or, rarely, tuberculosis.

Secretory otitis media results from obstruction of the eustachian tube. This causes a buildup of negative pressure in the middle ear that promotes transudation of sterile serous fluid from blood vessels in the membrane of the middle ear. Such effusion may be secondary to eustachian tube dysfunction from viral infection or allergy. It may also follow barotrauma (pressure injury caused by the inability to equalize pressures between the environment and the middle ear), as occurs during rapid aircraft descent in a person with an upper respiratory tract infection or during rapid underwater ascent in scuba diving (barotitis media).

Chronic secretory otitis media follows persistent eustachian tube dysfunction from mechanical obstruction (adenoidal tissue overgrowth or tumors), edema (allergic rhinitis or chronic sinus infection), or inadequate treatment for acute suppurative otitis media.

Acute otitis media is common in children; its incidence rises during the winter months,

paralleling the seasonal rise in nonbacterial respiratory tract infections. Chronic secretory otitis media most commonly occurs in children with tympanostomy tubes or those with a perforated tympanic membrane.

paralleling the seasonal rise in nonbacterial respiratory tract infections. Chronic secretory otitis media most commonly occurs in children with tympanostomy tubes or those with a perforated tympanic membrane.

COMPLICATIONS

Spontaneous rupture of the tympanic membrane

Persistent perforation

Chronic otitis media

Mastoiditis

Abscesses

Vertigo

Permanent hearing loss

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Clinical features of acute suppurative otitis media include severe, deep, throbbing pain (from pressure behind the tympanic membrane); signs of upper respiratory tract infection (sneezing or coughing); mild to very high fever; hearing loss (usually mild and conductive); tinnitus; dizziness; nausea; and vomiting. Other possible effects include bulging of the tympanic membrane, with concomitant erythema, and purulent drainage in the ear canal from tympanic membrane rupture. However, many patients are asymptomatic.

Acute secretory otitis media produces a severe conductive hearing loss—which varies from 15 to 35 dB, depending on the thickness and amount of fluid in the middle ear cavity— and, possibly, a sensation of fullness in the ear and popping, crackling, or clicking sounds on swallowing or with jaw movement. Accumulation of fluid may also cause the patient to hear an echo when he speaks and to experience a vague feeling of top-heaviness.

The cumulative effects of chronic otitis media include thickening and scarring of the tympanic membrane, decreased or absent tympanic membrane mobility, cholesteatoma (a cystlike mass in the middle ear) and, in chronic suppurative otitis media, a painless, purulent discharge. The extent of associated conductive

hearing loss varies with the size and type of tympanic membrane perforation and ossicular destruction.

hearing loss varies with the size and type of tympanic membrane perforation and ossicular destruction.

If the tympanic membrane has ruptured, the patient may state that the pain has suddenly stopped. Complications may include abscesses (brain, subperiosteal, and epidural), sigmoid sinus or jugular vein thrombosis, septicemia, meningitis, suppurative labyrinthitis, facial paralysis, and otitis externa.

The following factors increase a child’s risk of developing otitis media:

acute otitis media in the first year after birth (recurrent otitis media)

day care

family history of middle ear disease

formula feeding

male gender

sibling history of otitis media

smoking in the household

Acute otitis media may not produce any symptoms in the first few months of life; irritability may be the only indication of earache.

DIAGNOSIS

In acute suppurative otitis media, otoscopy reveals obscured or distorted bony landmarks of the tympanic membrane. Pneumatoscopy can show decreased tympanic membrane mobility, but this procedure is painful with an obviously bulging, erythematous tympanic membrane. The pain pattern is diagnostically significant: For example, in acute suppurative otitis media, pulling the auricle doesn’t exacerbate the pain. A culture of the ear drainage identifies the causative organism.

In acute secretory otitis media, otoscopic examination reveals tympanic membrane retraction, which causes the bony landmarks to appear more prominent.

Examination also detects clear or amber fluid behind the tympanic membrane. If hemorrhage into the middle ear has occurred, as in barotrauma, the tympanic membrane appears blue-black.

In chronic otitis media, patient history discloses recurrent or unresolved otitis media. Otoscopy shows thickening, sometimes scarring, and decreased mobility of the tympanic membrane; pneumatoscopy shows decreased or absent tympanic membrane movement. A history of recent air travel or scuba diving suggests barotitis media.

Tympanocentesis for microbiologic diagnosis is recommended for treatment failures and may be followed by myringotomy. Tympanometry, acoustic reflex measurement, or acoustic reflexometry may be needed to document the presence of fluid in the middle ear. White blood cell count is higher in bacterial otitis media than in sterile otitis media. Mastoid X-rays or computed tomography scan of the head or mastoids may show the spreading of the infection beyond the middle ear.

TREATMENT

In acute suppurative otitis media, antibiotic therapy includes amoxicillin. In areas with a high incidence of beta-lactamaseproducing H. influenzae and in patients who aren’t responding to ampicillin or amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium may be used. For those who are allergic to penicillin derivatives, therapy may include cefaclor or trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. Severe, painful bulging of the tympanic membrane usually necessitates myringotomy. Broad-spectrum antibiotics can help prevent acute suppurative otitis media in high-risk patients. A single dose of ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg is effective against major pathogens but is expensive and is reserved for very sick infants. In the patient with recurring otitis media, antibiotics must be used with discretion to prevent development of resistant strains of bacteria.

In acute secretory otitis media, inflation of the eustachian tube using Valsalva’s maneuver several times a day may be the only treatment required. Otherwise, nasopharyngeal decongestant therapy may be helpful. It should continue for at least 2 weeks and, sometimes, indefinitely, with periodic evaluation. If decongestant therapy fails, myringotomy and aspiration of middle ear fluid are necessary, followed by insertion of a polyethylene tube into the tympanic membrane, for immediate and prolonged equalization of pressure. The tube falls out spontaneously after 9 to 12 months. Concomitant treatment for the underlying cause (such as elimination of allergens, or adenoidectomy for hypertrophied adenoids) may also be helpful in correcting this disorder.

Treatment for chronic otitis media includes broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium or cefuroxime, for exacerbations of acute otitis media; elimination of eustachian tube obstruction; treatment for otitis externa; myringoplasty and tympanoplasty to reconstruct middle ear structures when thickening and scarring are present and, possibly, mastoidectomy. Cholesteatoma requires excision.

For a patient recovering from otitis media at home, teach these guidelines to help prevent a recurrence.

Instruct the patient how to recognize upper respiratory infections, and encourage early treatment. Encourage the patient to get a pneumococcal vaccine to prevent infections that can cause respiratory and aural infections.

Tell parents to wash children’s toys and promote frequent hand washing. For infants, tell parents to avoid the use of pacifiers and encourage breast-feeding for at least the first 6 months of the child’s life. It has been shown that breast milk contains antibodies that protect the infant from ear infections. If the child is bottle-fed, instruct the parents not to feed the infant in a supine position and not to put him to bed with a bottle. Explain that doing so could cause reflux of nasopharyngeal flora. Also, teach the parent to keep the child away from secondhand smoke.

To promote eustachian tube patency, instruct the patient to perform Valsalva’s maneuver several times a day, especially during airplane travel. Also, explain adverse reactions to the prescribed medications, emphasizing those that require immediate medical attention.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Explain all diagnostic tests and procedures. After myringotomy, maintain drainage flow. Don’t place cotton or plugs deeply into the ear canal; however, sterile cotton may be placed loosely in the external ear to absorb drainage. To prevent infection, change the cotton whenever it gets damp, and wash hands before and after giving ear care. Watch for and report headache, fever, severe pain, or disorientation.

After tympanoplasty, reinforce dressings, and observe for excessive bleeding from the ear canal. Administer analgesics as needed. Warn the patient against blowing his nose or getting the ear wet when bathing.

Encourage the patient to complete the prescribed course of antibiotic treatment. If nasopharyngeal decongestants are ordered, teach correct instillation.

Suggest application of heat to the ear to relieve pain. (See Preventing otitis media.)

Advise the patient with acute secretory otitis media to watch for and immediately report pain and fever—signs of secondary infection.

Identify and treat allergies.

Mastoiditis

Mastoiditis is a bacterial infection and inflammation of the air cells of the mastoid antrum. Although the prognosis is good with early treatment, possible complications include meningitis, facial paralysis, brain abscess, and suppurative labyrinthitis.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Bacteria that cause mastoiditis include pneumococci, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, beta-hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and gram-negative organisms. Mastoiditis is usually a complication of chronic otitis media; less frequently, it develops after acute otitis media. An accumulation of pus under pressure in the middle ear cavity results in necrosis of adjacent tissue and extension of the infection into the mastoid cells. Chronic systemic diseases or immunosuppression may also lead to mastoiditis. Anaerobic organisms play a role in chronic mastoiditis.

Acute otitis media increases a child’s risk of developing mastoiditis. If mastoiditis does occur in infants younger than age 1, the swelling occurs superior to the ear and pushes the auricle downward instead of outward. I.V. antibiotic treatment choice includes ampicillin or cefuroxime. Before antibiotics, mastoiditis was one of the leading causes of death in children; now, it’s uncommon and less dangerous.

COMPLICATIONS

Destruction of the mastoid bone

Facial paralysis

Meningitis

Partial or complete hearing loss

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Primary clinical features include a dull ache and tenderness in the area of the mastoid process, low-grade fever, headache, and a thick, purulent discharge that gradually becomes more profuse, possibly leading to otitis externa.

Postauricular erythema and edema may push the auricle out from the head; pressure within the edematous mastoid antrum may produce swelling and obstruction of the external ear canal, causing conductive hearing loss.

DIAGNOSIS

X-rays or computed tomography scan of the mastoid area reveal hazy mastoid air cells; the bony walls between the cells appear decalcified. Audiometric testing may reveal a conductive hearing loss. Physical examination shows a dull, thickened, and edematous tympanic membrane, if the membrane isn’t concealed by obstruction. During examination, the external ear canal is cleaned; persistent oozing into the canal indicates perforation of the tympanic membrane.

TREATMENT

Treatment for mastoiditis consists of intense parenteral antibiotic therapy. Reasonable initial antibiotic choices include ceftriaxone with nafcillin or clindamycin. If bone damage is minimal, myringotomy or tympanocentesis drains purulent fluid and provides a specimen of discharge for culture and sensitivity testing. Recurrent or persistent infection or signs of intracranial complications necessitate simple mastoidectomy. This procedure involves removal of the diseased bone and cleaning of the affected area, after which a drain is inserted.

A chronically inflamed mastoid requires radical mastoidectomy (excision of the posterior wall of the ear canal, remnants of the tympanic membrane, and the malleus and incus, although these bones are usually destroyed by infection before surgery). The stapes and facial nerve remain intact. Radical mastoidectomy, which is seldom necessary because of antibiotic therapy, doesn’t drastically affect the patient’s hearing because significant hearing loss precedes surgery. With either surgical procedure, the patient continues oral antibiotic therapy for several weeks after surgery and facility discharge. The prognosis is good if treatment is started early.

Indications for immediate surgical intervention include meningitis, brain abscess, cavernous sinus thrombosis, acute suppurative labyrinthitis, and facial palsy.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

After simple mastoidectomy, give pain medication as needed. Check wound drainage and reinforce dressings (the surgeon usually changes the dressing daily and removes the drain in 72 hours). Check the patient’s hearing, and watch for signs of complications, especially infection (either localized or extending to the brain); facial nerve paralysis, with unilateral facial drooping; bleeding; and vertigo, especially when the patient stands.

After radical mastoidectomy, the wound is packed with petroleum gauze or gauze treated with an antibiotic ointment. Give pain medication before the packing is removed, on the fourth or fifth postoperative day.

Because of stimulation to the inner ear during surgery, the patient may feel dizzy and nauseated for several days afterward. Keep the side rails up, and assist the patient with ambulation. Also, give antiemetics as needed.

Before discharge, teach the patient and his family how to change and care for the dressing. Urge compliance with the prescribed antibiotic treatment, and promote regular follow-up care.

If the patient is an elderly person or diabetic, evaluate him for malignant otitis externa.

Encourage the patient to seek early treatment for ear infections.

Otosclerosis

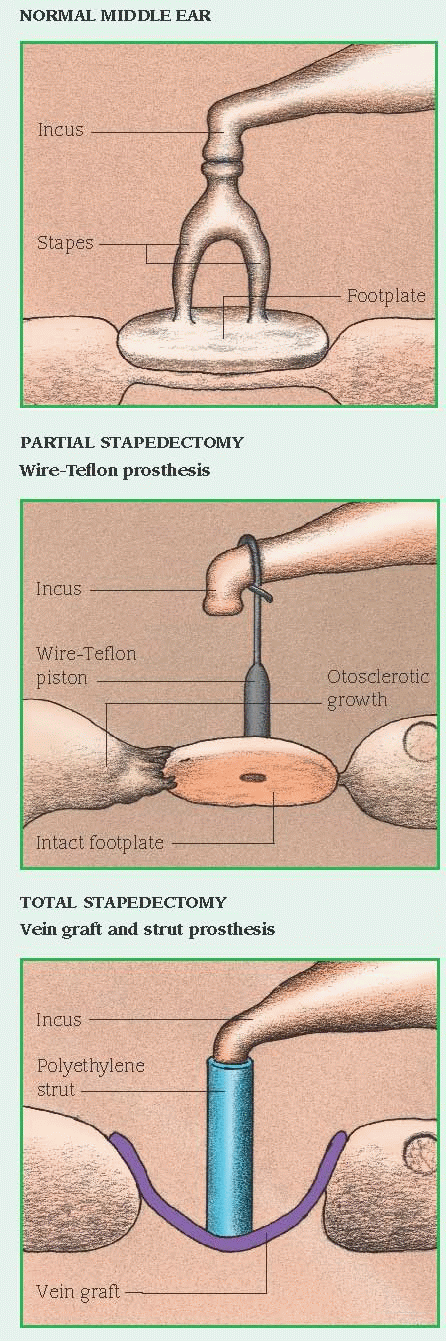

The most common cause of chronic, progressive conductive hearing loss, otosclerosis is the slow formation of spongy bone in the otic capsule, particularly at the oval window. With surgery, the prognosis is good.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Otosclerosis appears to result from a genetic factor transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait; many patients report family histories of hearing loss (excluding presbycusis). Pregnancy may trigger onset of this condition.

Otosclerosis occurs in at least 10% of the U.S. population. It’s three times more prevalent in females than in males, usually affecting people between ages 15 and 30. Whites are most susceptible.

COMPLICATIONS

Bilateral conductive hearing loss

Taste disturbance

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Spongy bone in the otic capsule immobilizes the footplate of the normally mobile stapes, disrupting the conduction of vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the cochlea. This causes progressive unilateral hearing loss, which may advance to bilateral deafness. Other symptoms include tinnitus and paracusis of Willis (hearing

conversation better in a noisy environment than in a quiet one).

conversation better in a noisy environment than in a quiet one).

DIAGNOSIS

Early diagnosis is based on a Rinne test that shows bone conduction lasting longer than air conduction (normally, the reverse is true). As otosclerosis progresses, bone conduction also deteriorates. Audiometric testing reveals hearing loss ranging from 60 dB in early stages to total loss. Weber’s test detects sound lateralizing to the more affected ear. Physical examination reveals a normal tympanic membrane. Head computed tomography scan and X-ray help distinguish otosclerosis from other causes of hearing loss.

TREATMENT

Treatment consists of stapedectomy (removal of the stapes) and insertion of a prosthesis to restore partial or total hearing. This procedure is performed on only one ear at a time, beginning with the ear that has suffered greater damage. Alternative surgery includes stapedotomy (creation of a small hole in the stapes’ footplate), through which a wire and piston are inserted. (See Types of stapedectomy.) Recent procedural innovations involve laser surgery. Postoperatively, treatment includes antibiotics to prevent infection. If surgery isn’t possible, a hearing aid (air conduction aid with molded ear insert receiver) enables the patient to hear conversation in normal surroundings, although this therapy isn’t as effective as stapedectomy.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

During the first 24 hours after surgery, keep the patient supine, with the affected ear facing upward (to maintain the position of the graft). Enforce bed rest with bathroom privileges for 48 hours. Because the patient may be dizzy, keep the side rails up, and assist him with ambulation. Assess for pain and vertigo, which may be relieved with repositioning or prescribed medication.

Watch for and report postoperative facial drooping, which may indicate swelling of or around the facial nerve.

Tell the patient that his hearing won’t return until edema subsides and packing is removed.

Before discharge, instruct the patient to avoid loud noises and sudden pressure changes (such as those that occur while diving or flying) until healing is complete (usually 6 months). Advise the patient not to blow his nose for at least 1 week to prevent contaminated air and bacteria from entering the eustachian tube.

Stress the importance of protecting the ears against cold; avoiding any activities that provoke dizziness, such as straining, bending, or heavy lifting and, if possible, avoiding contact with anyone who has an upper respiratory tract infection. Teach the patient and his family how to change the external ear dressing (eye or gauze pad) and care for the incision. Emphasize the need to complete the prescribed antibiotic regimen and to return for scheduled follow-up care.

Infectious myringitis

Acute infectious myringitis is characterized by inflammation, hemorrhage, and effusion of fluid into the tissue at the end of the external ear canal and the tympanic membrane. This selflimiting disorder (resolving spontaneously within 3 days to 2 weeks) commonly follows acute otitis media or upper respiratory tract infection.

Chronic granular myringitis, a rare inflammation of the squamous layer of the tympanic membrane, causes gradual hearing loss. Without specific treatment, this condition can lead to stenosis of the ear canal, as granulation extends from the tympanic membrane to the external ear.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Acute infectious myringitis usually follows viral infection but may also result from infection with bacteria (pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, beta-hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci) or any other organism that can cause acute otitis media. Myringitis is a rare sequela of atypical pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The cause of chronic granular myringitis is unknown.

Acute infectious myringitis frequently occurs epidemically in children.

COMPLICATIONS

Gradual hearing loss

Stenosis of the ear canal

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Acute infectious myringitis begins with severe ear pain, commonly accompanied by tenderness over the mastoid process. Small, reddened, inflamed blebs form in the canal, on the tympanic membrane and, with bacterial invasion, in the middle ear. Fever and hearing loss are rare unless fluid accumulates in the middle ear or a large bleb totally obstructs the external auditory meatus. Spontaneous rupture of these blebs may cause bloody discharge. Chronic granular myringitis produces pruritus, purulent discharge, and gradual hearing loss.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of acute infectious myringitis is based on physical examination showing characteristic blebs and a typical patient history. Culture and sensitivity testing of exudate identifies secondary infection. In chronic granular myringitis, physical examination may reveal granulation extending from the tympanic membrane to the external ear.