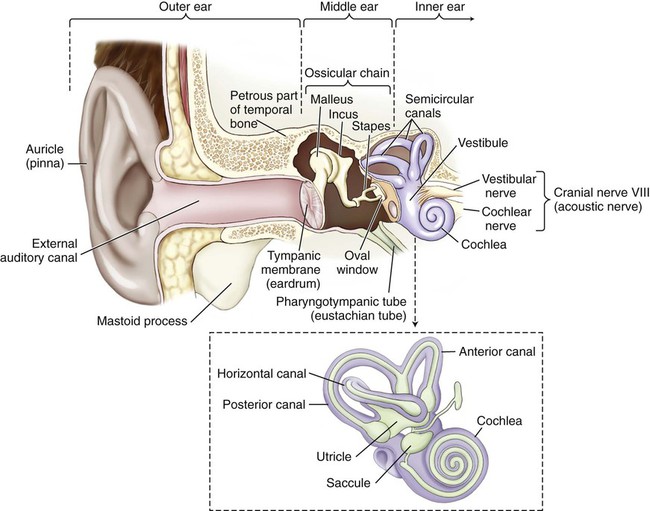

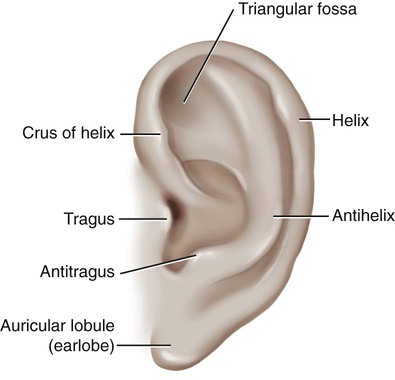

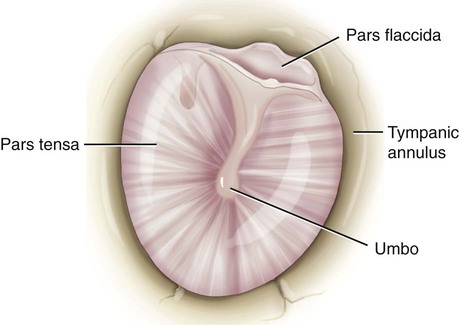

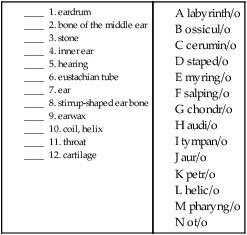

The ear is regionally divided into the outer, middle, and inner ear (Fig. 14-1). Sound travels through air, bone, and fluid across these divisions. Sound waves are initially gathered by the flesh-covered elastic cartilage of the outer ear called the pinna, or auricle (Fig. 14-2). The auricular cartilage is folded into several distinct structures with separate names. The helix is the upper outer rim of the auricle, whereas the antihelix is the inner curve that is parallel to the helix. The antihelix has two “legs,” or crura (sing. crus), that divide to form a shallow depression between them, referred to as the triangular fossa. The tragus is the fleshy tag of tissue with a tuft of hair on its underside that covers the opening of the external auditory canal. The antitragus is the small raised prominence that is opposite to the tragus. It is important to remember that elastic cartilage is covered by a layer of connective tissue called perichondrium. When this is separated from the cartilage by trauma, deformities of the pinna may occur. The lobule, usually referred to as the earlobe, is the only noncartilaginous part of the external ear. This fleshy protuberance is composed of adipose tissue. The tympanic membrane (TM), or eardrum, marks the end of the external ear and the beginning of the middle ear (Fig. 14-3). This concave membrane of the eardrum is attached to an almost complete ring of bone called the tympanic annulus. The membrane is composed of a thick, taut part (the pars tensa) and a thin, flexible part (the pars flaccida). The center of the membrane is pulled inward, forming a shallow depression termed the umbo. Because the membrane is extremely delicate and vulnerable to perforation and infection, the additional terms naming structures of the eardrum are necessary to specify where the injury occurs. Once sound is conducted to the oval window, it is transmitted to a structure called the labyrinth, or the inner ear. A membranous labyrinth is enclosed within a bony labyrinth. Between the two, and surrounding the inner labyrinth, is a fluid called perilymph. Within the membranous labyrinth is a fluid called endolymph. Hair cells within the inner ear fluids act as nerve endings that function as sensory receptors for hearing and equilibrium. Tiny calcium carbonate crystals called otoliths are attached to these hair cells and act as receptors to aid in balance. The outer, bony labyrinth is composed of three parts: the vestibule, the semicircular canals, and the cochlea. The vestibule and semicircular canals provide information about the body’s sense of equilibrium, whereas the cochlea is an organ of hearing. Within the vestibule, two structures called the utricle and the saccule function to determine the body’s static (nonmoving) equilibrium (Fig. 14-1, inset). A specialized patch of epithelium, called the macula, found in both the utricle and the saccule, provides information about the position of the head and a sense of acceleration and deceleration. The semicircular canals detect dynamic equilibrium or a sense of sudden rotation through the function of a structure called the crista ampullaris. Combining Forms for Anatomy and Physiology of the Ear Terms Related to Congenital Disorders of the Ear (QØØ-Q99) Terms Related to Diseases of the External Ear (H6Ø-H62)

Ear and Mastoid Process

Recognize and use terms related to the anatomy and physiology of the ear.

Recognize and use terms related to the anatomy and physiology of the ear.

Recognize and use terms related to the pathology of the ear.

Recognize and use terms related to the pathology of the ear.

Anatomy and Physiology

Outer (External) Ear

Inner Ear

Meaning

Combining Form

antrum

antr/o

auricle, pinna

auricul/o

cartilage

chondr/o, cartilag/o

cerumen, earwax

cerumin/o

cochlea

cochle/o

ear

ot/o

eardrum

tympan/o, myring/o

eustachian tube

salping/o

hearing

acous/o, audi/o, aur/o

helix, coil

helic/o

labyrinth, inner ear

labyrinth/o

mastoid process

mastoid/o

ossicle, small bone

ossicul/o

petrous bone

petros/o

spot, macula

macul/o

stapes

staped/o

stone

petr/o, lith/o

vestibule

vestibul/o

Pathology

Term

Word Origin

Definition

macrotia

macro- large

ot/o ear

-ia condition

A condition of abnormally large auricles.

microtia

micro- small, tiny

ot/o ear

-ia condition

A condition of abnormally small auricles.

Term

Word Origin

Definition

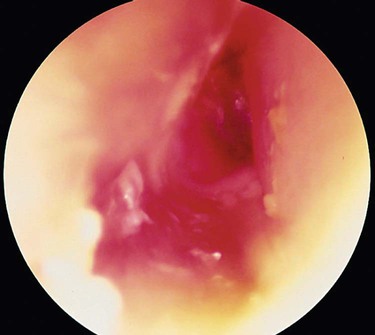

cholesteatoma, external ear

chol/e bile

steat/o fat

-oma mass, tumor

Cystic mass composed of epithelial cells and cholesterol. Can occur also in middle ear (Fig. 14-4).

exostosis of external ear

ex- out

oste/o bone

-osis abnormal condition

Bony growth usually due to chronic irritation.

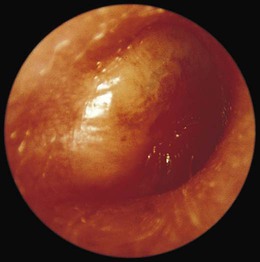

otitis externa

ot/o ear

-itis inflammation

extern/o outer

-a noun ending

Inflammation of the pinna/auricle (Fig. 14-5).

perichondritis, auricular

peri- around, surrounding

chondr/o cartilage

-itis inflammation

Inflammation of the perichondrium of the external ear. May result in a deformity referred to as “cauliflower ear.”

stenosis of external ear canal, acquired

stenosis abnormal condition of narrowing

A narrowing of the auditory canal that develops after birth. ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine