EXAMINATION TIP Using an Otoscope Correctly

When the patient reports an earache, use an otoscope to inspect ear structures closely. Follow these techniques to obtain the best view and ensure patient safety.

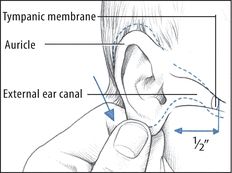

CHILD YOUNGER THAN AGE 3

To inspect an infant’s or a young child’s ear, grasp the lower part of the auricle and pull it down and back to straighten the upward S curve of the external canal. Then gently insert the speculum into the canal no more than ½” (1.2 cm).

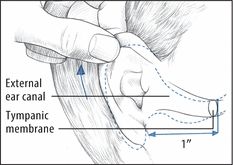

ADULT

To inspect an adult’s ear, grasp the upper part of the auricle and pull it up and back to straighten the external canal. Then insert the speculum about 1” (2.5 cm). Also, use this technique for children ages 3 and older.

- Cerumen impaction. Impacted cerumen (earwax) may cause a sensation of vague pain, blockage, or fullness in the ear. Additional features include partial hearing loss, itching and, possibly, dizziness.

- Herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). Herpes zoster oticus causes burning or stabbing ear pain, commonly associated with ear vesicles. The patient also complains of hearing loss and vertigo. Associated signs and symptoms include transitory, ipsilateral, facial paralysis; partial loss of taste; tongue vesicles; and nausea and vomiting.

- Keratosis obturans. Mild ear pain is common with keratosis obturans, along with otorrhea and tinnitus. Inspection reveals a white glistening plug obstructing the external meatus.

- Mastoiditis (acute). Mastoiditis causes a dull ache and redness behind the ear accompanied by a fever that may suddenly increase. The eardrum appears dull and edematous and may perforate, and soft tissue near the eardrum may sag. A purulent discharge is seen in the external canal.

- Ménière’s disease. Ménière’s disease is an inner ear disorder that can produce a sensation of fullness in the affected ear. Its classic effects, however, include severe vertigo, tinnitus, and sensorineural hearing loss. The patient may also experience nausea and vomiting, diaphoresis, and nystagmus.

- Otitis externa. Earache characterizes acute and malignant otitis externa. Acute otitis externa begins with mild to moderate or intense ear pain that occurs with tragus manipulation. The pain may be accompanied by a low-grade fever, sticky yellow or purulent ear discharge, partial hearing loss, and a feeling of blockage. Later, ear pain intensifies, causing the entire side of the head to ache and throb. Fever may reach 104°F (40°C). Examination reveals swelling of the tragus, external meatus, and external canal; eardrum erythema; and lymphadenopathy. The patient also complains of dizziness and malaise.

Malignant otitis externa abruptly causes ear pain that’s aggravated by moving the auricle or tragus. The pain is accompanied by intense itching, purulent ear discharge, a fever, parotid gland swelling, and trismus. Examination reveals a swollen external canal with exposed cartilage and temporal bone. Cranial nerve palsy may occur.

- Otitis media (acute). Otitis media is middle ear inflammation that may be serous or suppurative. Acute serous otitis media may cause a feeling of fullness in the ear, hearing loss, and a vague sensation of top-heaviness. The eardrum may be slightly retracted, amber, and marked by air bubbles and a meniscus, or it may be blue-black from hemorrhage.

Severe, deep, throbbing ear pain; hearing loss; and a fever that may reach 102°F (38.9°C) characterize acute suppurative otitis media. The pain increases steadily over several hours or days and may be aggravated by pressure on the mastoid antrum. Perforation of the eardrum is possible. Before rupture, the eardrum appears bulging and fiery red. Rupture causes purulent drainage and relieves the pain.

Chronic otitis media usually isn’t painful except during exacerbations. Persistent pain and discharge from the ear suggest osteomyelitis of the skull base or cancer.

Special Considerations

Administer an analgesic, and apply heat to relieve discomfort. Instill eardrops if necessary.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient or caregiver to instill eardrops correctly. Explain the importance of taking prescribed antibiotics correctly. Explain ways to avoid vertigo and ear trauma.

Pediatric Pointers

Common causes of earache in children are acute otitis media and the insertion of foreign bodies that become lodged or infected. Be alert for discharge from the opposite or both eyes and, in a young child, crying or ear tugging — nonverbal clues to earache.

To examine the child’s ears, place him in a supine position with his arms extended and held securely by his parent. Then hold the otoscope with the handle pointing toward the top of the child’s head, and brace it against him using one or two fingers. Because an ear examination may upset the child with an earache, save it for the end of your physical examination.

REFERENCES

Brehm, J. M., Celedón, J. C., Soto-Quiros, M. E., Avila, L., Hunninghake, G. M., Forno E., … Litonjua, A. A. (2009). Serum vitamin D levels and markers of severity of childhood asthma in Costa Rica. American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine, 179, 765–771.

Peters, B. S., dos Santos, L. C., Fisberg, M., Wood, R. J., & Martini, L. A. (2009). Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in Brazilian adolescents. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 54, 15–21.

Van Belle, T. L., Gysemans, C., & Mathieu, C. (2011). Vitamin D in autoimmune, infectious and allergic diseases: A vital player? Best Practice Research in Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 25, 617–632.

Edema, Generalized

A common sign in severely ill patients, generalized edema is the excessive accumulation of interstitial fluid throughout the body. Its severity varies widely; slight edema may be difficult to detect, especially if the patient is obese, whereas massive edema is immediately apparent.

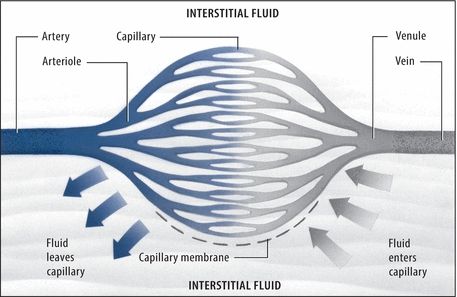

Understanding Fluid Balance

Normally, fluid moves freely between the interstitial and intravascular spaces to maintain homeostasis. Four basic pressures control fluid shifts across the capillary membrane that separates these spaces:

- Capillary hydrostatic pressure (the internal fluid pressure on the capillary membrane)

- Interstitial fluid pressure (the external fluid pressure on the capillary membrane)

- Osmotic pressure (the fluid-attracting pressure from protein concentration within the capillary)

- Interstitial osmotic pressure (the fluid-attracting pressure from protein concentration outside the capillary)

Here’s how these pressures maintain homeostasis. Normally, capillary hydrostatic pressure is greater than plasma osmotic pressure at the capillary’s arterial end, forcing fluid out of the capillary. At the capillary’s venous end, the reverse is true: The plasma osmotic pressure is greater than the capillary hydrostatic pressure, drawing fluid into the capillary. Normally, the lymphatic system transports excess interstitial fluid back to the intravascular space.

Edema results when this balance is upset by increased capillary permeability, lymphatic obstruction, persistently increased capillary hydrostatic pressure, decreased plasma osmotic or interstitial fluid pressure, or dilation of precapillary sphincters.

Generalized edema is typically chronic and progressive. It may result from cardiac, renal, endocrine, lymphatic, or hepatic disorders as well as from severe burns, malnutrition, the effects of certain drugs and treatments, and after having a mastectomy.

Common factors responsible for edema are hypoalbuminemia and excess sodium ingestion or retention, both of which influence plasma osmotic pressure. (See Understanding Fluid Balance.) Cyclic edema associated with increased aldosterone secretion may occur in premenopausal women.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Quickly determine the location and severity of edema, including the degree of pitting. (See Edema: Pitting or Nonpitting?) If the patient has severe edema, promptly take his vital signs, and check for jugular vein distention and cyanotic lips. Auscultate the lungs and heart. Be alert for signs of cardiac failure or pulmonary congestion, such as crackles, muffled heart sounds, or a ventricular gallop. Unless the patient is hypotensive, place him in Fowler’s position to promote lung expansion. Prepare to administer oxygen and an I.V. diuretic. Have emergency resuscitation equipment nearby.

EXAMINATION TIP Edema: Pitting or Nonpitting?

EXAMINATION TIP Edema: Pitting or Nonpitting?

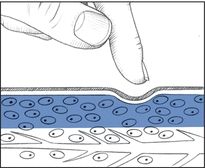

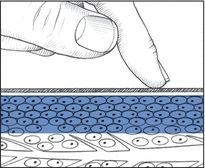

To differentiate pitting from nonpitting edema, press your finger against a swollen area for 5 seconds and then quickly remove it.

With pitting edema, pressure forces fluid into the underlying tissues, causing an indentation that slowly fills. To determine the severity of pitting edema, estimate the indentation’s depth in centimeters: 1+ (1 cm), 2+ (2 cm), 3+ (3 cm), or 4+ (4 cm).

With nonpitting edema, pressure leaves no indentation because fluid has coagulated in the tissues. Typically, the skin feels unusually tight and firm.

Pitting Edema (4+)

Nonpitting Edema

History and Physical Examination

When the patient’s condition permits, obtain a complete medical history. First, note when the edema began. Does it move throughout the course of the day — for example, from the upper extremities to the lower, periorbitally, or within the sacral area? Is the edema worse in the morning or at the end of the day? Is it affected by position changes? Is it accompanied by shortness of breath or pain in the arms or legs? Find out how much weight the patient has gained. Has his urine output changed in quantity or quality?

Next, ask about previous burns or cardiac, renal, hepatic, endocrine, or GI disorders. Have the patient describe his diet so you can determine whether he suffers from protein malnutrition. Explore his drug history, and note recent I.V. therapy.

Begin the physical examination by comparing the patient’s arms and legs for symmetrical edema. Also, note ecchymoses and cyanosis. Assess the back, sacrum, and hips of the bedridden patient for dependent edema. Palpate peripheral pulses, noting whether hands and feet feel cold. Finally, perform a complete cardiac and respiratory assessment.

Medical Causes

- Angioneurotic edema or angioedema. Recurrent attacks of acute, painless, nonpitting edema involving the skin and mucous membranes — especially those of the respiratory tract, face, neck, lips, larynx, hands, feet, genitalia, or viscera — may be the result of a food or drug allergy or emotional stress, or they may be hereditary. Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea accompany visceral edema; dyspnea and stridor accompany life-threatening laryngeal edema.

- Burns. Edema and associated tissue damage vary with the severity of the burn. Severe generalized edema (4+) may occur within 2 days of a major burn; localized edema may occur with a less severe burn.

- Cirrhosis. Patients may display generalized edema of the body with a “puffy” appearance during the advanced stages of cirrhosis. As the disease progresses, healthy liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue that ultimately leads to inadequate liver function. In addition, patients may also have edema in lower areas of the body, displayed in the legs and abdomen (ascites). Other symptoms include difficulty concentrating, sleeping problems, poor memory, jaundice, and dark-colored urine.

- Heart failure. Severe, generalized pitting edema — occasionally anasarca — may follow leg edema late in this disorder. The edema may improve with exercise or elevation of the limbs and is typically worse at the end of the day. Among other classic late findings are hemoptysis, cyanosis, marked hepatomegaly, clubbing, crackles, and a ventricular gallop. Typically, the patient has tachypnea, palpitations, hypotension, weight gain despite anorexia, nausea, a slowed mental response, diaphoresis, and pallor. Dyspnea, orthopnea, tachycardia, and fatigue typify left-sided heart failure; jugular vein distention, enlarged liver, and peripheral edema typify right-sided heart failure.

- Malnutrition. Anasarca in malnutrition may mask dramatic muscle wasting. Malnutrition also typically causes muscle weakness; lethargy; anorexia; diarrhea; apathy; dry, wrinkled skin; and signs of anemia, such as dizziness and pallor.

- Myxedema. With myxedema, which is a severe form of hypothyroidism, generalized nonpitting edema is accompanied by dry, flaky, inelastic, waxy, pale skin; a puffy face; and an upper eyelid droop. Observation also reveals masklike facies, hair loss or coarsening, and psychomotor slowing. Associated findings include hoarseness, weight gain, fatigue, cold intolerance, bradycardia, hypoventilation, constipation, abdominal distention, menorrhagia, impotence, and infertility.

- Nephrotic syndrome. Although nephrotic syndrome is characterized by generalized pitting edema, it’s initially localized around the eyes. With severe cases, anasarca develops, increasing body weight by up to 50%. Other common signs and symptoms are ascites, anorexia, fatigue, malaise, depression, and pallor.

- Pericardial effusion. With pericardial effusion, generalized pitting edema may be most prominent in the arms and legs. It may be accompanied by chest pain, dyspnea, orthopnea, a nonproductive cough, a pericardial friction rub, jugular vein distention, dysphagia, and a fever.

- Pericarditis (chronic constructive). Resembling right-sided heart failure, pericarditis usually begins with pitting edema of the arms and legs that may progress to generalized edema. Other signs and symptoms include ascites, Kussmaul’s sign, dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, abdominal distention, and hepatomegaly.

- Renal failure. With acute renal failure, generalized pitting edema occurs as a late sign. With chronic renal failure, edema is less likely to become generalized; its severity depends on the degree of fluid overload. Both forms of renal failure cause oliguria, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, hypertension, dyspnea, crackles, dizziness, and pallor.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Any drug that causes sodium retention may aggravate or cause generalized edema. Examples include antihypertensives, corticosteroids, androgenic and anabolic steroids, estrogens, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as phenylbutazone, ibuprofen, and naproxen.

- Treatments. I.V. saline solution infusions and internal feedings may cause sodium and fluid overload, resulting in generalized edema, especially in patients with cardiac or renal disease.

Special Considerations

Position the patient with his limbs above heart level to promote drainage. Periodically reposition him to avoid pressure ulcers. If the patient develops dyspnea, lower his limbs, elevate the head of the bed, and administer oxygen. Massage reddened areas, especially where dependent edema has formed (for example, the back, sacrum, hips, or buttocks). Prevent skin breakdown in these areas by placing a pressure mattress, lamb’s wool pad, or flotation ring on the patient’s bed. Restrict fluids and sodium, and administer a diuretic or I.V. albumin.

Monitor the patient’s intake and output and daily weight. Also, monitor serum electrolyte levels — especially sodium and albumin. Prepare the patient for blood and urine tests, X-rays, echocardiography, or an electrocardiogram.

Patient Counseling

Explain the signs and symptoms of edema the patient should report. Discuss foods and fluids the patient should avoid.

Pediatric Pointers

Renal failure in children commonly causes generalized edema. Monitor fluid balance closely. Remember that a fever or diaphoresis can lead to fluid loss, so promote fluid intake.

Kwashiorkor — protein deficiency malnutrition — is more common in children than in adults and causes anasarca.

Geriatric Pointers

Elderly patients are more likely to develop edema for several reasons, including decreased cardiac and renal function and, in some cases, poor nutritional status. Use caution when giving older patients I.V. fluids or medications that can raise sodium levels and thereby increase fluid retention.

REFERENCES

Barrera, F., & George, J. (2013). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: More than just ectopic fat accumulation. Drug Discovery Today, 10(1–2), e47–e54.

Musso, G., Gambino, R., & Cassader, M. (2010). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease from pathogenesis to management: An update. Obesity Review, 11(6), 430–445.

Edema of the Arm

The result of excess interstitial fluid in the arm, arm edema may be unilateral or bilateral and may develop gradually or abruptly. It may be aggravated by immobility and alleviated by arm elevation and exercise.

Arm edema signals a localized fluid imbalance between the vascular and interstitial spaces. (See Understanding Fluid Balance, page 278.) It commonly results from trauma, venous disorders, toxins, or certain treatments.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Remove rings, bracelets, and watches from the patient’s affected arm. These items may act as a tourniquet. Make sure that the patient’s sleeves don’t inhibit fluid drainage or blood flow.

History and Physical Examination

One of the first questions to ask when taking the patient’s history is, “How long has your arm been swollen?” Then find out if the patient also has arm pain, numbness, or tingling. Does exercise or arm elevation decrease the edema? Ask about recent arm injury, such as burns or insect stings. Also, note recent I.V. therapy, surgery, or radiation therapy for breast cancer.

Determine the edema’s severity by comparing the size and symmetry of both arms. Use a tape measure to determine the exact girth, and mark the location where the measurement was obtained in order to make comparative measurements later. Make sure to note whether the edema is unilateral or bilateral, and test for pitting. (See Edema: Pitting or Nonpitting? page 279.) Next, examine and compare the color and temperature of both arms. Look for erythema and ecchymoses and for wounds that suggest injury. Palpate and compare radial and brachial pulses. Finally, look for arm tenderness and decreased sensation or mobility. If you detect signs of neurovascular compromise, elevate the arm.

Medical Causes

- Angioneurotic edema. Angioneurotic edema is a common reaction that’s characterized by the sudden onset of painless, nonpruritic edema affecting the hands, feet, eyelids, lips, face, neck, genitalia, or viscera. Although swelling usually doesn’t itch, it may burn and tingle. If edema spreads to the larynx, signs of respiratory distress may occur.

- Arm trauma. Shortly after a crush injury, severe edema may affect the entire arm. Ecchymoses or superficial bleeding, pain or numbness, and paralysis may occur.

- Burns. Two days or less after injury, arm burns may cause mild to severe edema, pain, and tissue damage.

- Envenomation. Envenomation by snakes, aquatic animals, or insects initially may cause edema around the bite or sting that quickly spreads to the entire arm. Pain, erythema, and pruritus at the site are common; paresthesia occurs occasionally. Later, the patient may develop generalized signs and symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, weakness, muscle cramps, a fever, chills, hypotension, a headache and, in severe cases, dyspnea, seizures, and paralysis.

- Superior vena cava syndrome. Bilateral arm edema usually progresses slowly and is accompanied by facial and neck edema. Dilated veins mark these edematous areas. The patient also complains of a headache, vertigo, and vision disturbances.

- Thrombophlebitis. Thrombophlebitis, which can result from peripherally inserted central catheters and arm Port-A-Caths, may cause arm edema, pain, and warmth. Deep vein thrombophlebitis can also produce cyanosis, a fever, chills, and malaise; superficial thrombophlebitis also causes redness, tenderness, and induration along the vein.

Other Causes

- Treatments. Localized arm edema may result from infiltration of I.V. fluid into the interstitial tissue. A radical or modified radical mastectomy that disrupts lymphatic drainage may cause edema of the entire arm, as can axillary lymph node dissection. Also, radiation therapy for breast cancer may produce arm edema immediately after treatment or months later.

Special Considerations

Treatment of the patient with arm edema varies according to the underlying cause. General care measures include elevation of the arm, frequent repositioning, and appropriate use of bandages and dressings to promote drainage and circulation. Make sure to provide patients with meticulous skin care to prevent breakdown and formation of pressure ulcers. Also, administer an analgesic and anticoagulant as needed.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient in postoperative arm care. Teach arm exercises that will help prevent lymphedema.

Pediatric Pointers

Arm edema rarely occurs in children, except as part of generalized edema, but it may result from arm trauma, such as burns and crush injuries.

REFERENCES

Ballots, J. C., Tamaoki, M. J., Atallah, A. N., Albertoni, W. M., dos Santos, J. B., & Faloppa, F. (2010). Treatment of reducible unstable fractures of the distal radius in adults: A randomised controlled trial of De Palma percutaneous pinning versus bridging external fixation. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 11, 137.

Schneppendahl, J., Windolf, J., & Kaufmann, R. A. (2012). Distal radius fractures: Current concepts. Journal of Hand Surgery Am, 37, 1718–1725.

Edema of the Face

Facial edema refers to either localized swelling — around the eyes, for example — or more generalized facial swelling that may extend to the neck and upper arms. Occasionally painful, this sign may develop gradually or abruptly. Sometimes it precedes the onset of peripheral or generalized edema. Mild edema may be difficult to detect; the patient or someone who’s familiar with his appearance may report it before it’s noticed during assessment.

Facial edema results from disruption of the hydrostatic and osmotic pressures that govern fluid movement between the arteries, veins, and lymphatics. (See Understanding Fluid Balance, page 278.) It may result from venous, inflammatory, and certain systemic disorders; trauma; allergy; malnutrition; or the effects of certain drugs, tests, and treatments.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has facial edema associated with burns or if he reports recent exposure to an allergen, quickly evaluate his respiratory status. Edema may also affect his upper airway, causing life-threatening obstruction. If you detect audible wheezing, inspiratory stridor, or other signs of respiratory distress, administer epinephrine. For the patient in severe distress — with absent breath sounds and cyanosis — tracheal intubation, cricothyroidotomy, or tracheotomy may be required. Always administer oxygen.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in severe distress, take his health history. Ask if facial edema developed suddenly or gradually. Is it more prominent in early morning, or does it worsen throughout the day? Has the patient gained weight? If so, how much and over what length of time? Has he noticed a change in his urine color or output? In his appetite? Take a drug history and ask about recent facial trauma.

Begin the physical examination by characterizing the edema. Is it localized to one part of the face, or does it affect the entire face or other parts of the body? Determine if the edema is pitting or nonpitting, and grade its severity. (See Edema: Pitting or Nonpitting? page 279.) Next, take the patient’s vital signs, and assess his neurologic status. Examine the oral cavity to evaluate dental hygiene and look for signs of infection. Visualize the oropharynx, and look for soft tissue swelling.

Medical Causes

- Allergic reaction. Facial edema may characterize local allergic reactions and anaphylaxis. With life-threatening anaphylaxis, angioneurotic facial edema may occur with urticaria and flushing. (See Recognizing Angioneurotic Edema.) Airway edema causes hoarseness, stridor, and bronchospasm with dyspnea and tachypnea. Signs of shock, such as hypotension and cool, clammy skin, may also occur. A localized reaction produces facial edema, erythema, and urticaria.

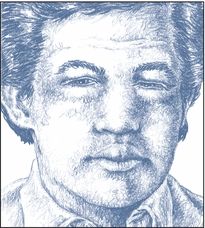

Recognizing Angioneurotic Edema

Most dramatic in the lips, eyelids, and tongue, angioneurotic edema commonly results from an allergic reaction. It’s characterized by the rapid onset of painless, nonpitting, subcutaneous swelling that usually resolves in 1 to 2 days. This type of edema may also involve the hands, feet, genitalia, and viscera; laryngeal edema may cause life-threatening airway obstruction.

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis. Cavernous sinus thrombosis, a rare but serious disorder, may begin with unilateral edema that quickly progresses to bilateral edema of the forehead, base of the nose, and eyelids. It may also produce chills, a fever, a headache, nausea, lethargy, exophthalmos, and eye pain.

- Chalazion. A chalazion causes localized swelling and tenderness of the affected eyelid, accompanied by a small red lump on the conjunctival surface.

- Conjunctivitis. Conjunctivitis causes eyelid edema, excessive tearing, and itchy, burning eyes. Inspection reveals a thick purulent discharge, crusty eyelids, and conjunctival injection. Corneal involvement causes photophobia and pain.

- Dacryoadenitis. Severe periorbital swelling characterizes dacryoadenitis, which may also cause conjunctival injection, purulent discharge, and temporal pain.

- Dacryocystitis. Lacrimal sac inflammation causes prominent eyelid edema and constant tearing. With acute cases, pain and tenderness near the tear sac accompany purulent discharge.

- Facial burns. Burns may cause extensive edema that impairs respiration. Additional findings include singed nasal hairs, red mucosa, sooty sputum, and signs of respiratory distress, such as inspiratory stridor.

- Facial trauma. The extent of edema varies with the type of injury. For example, a contusion may cause localized edema, whereas a nasal or maxillary fracture causes more generalized edema. Associated features also depend on the type of injury.

- Herpes zoster ophthalmicus (shingles). With shingles, edematous and red eyelids are usually accompanied by excessive tearing and a serous discharge. Severe unilateral facial pain may occur several days before vesicles erupt.

- Myxedema. Myxedema eventually causes generalized facial edema; waxy, dry skin; hair loss or coarsening; and other signs of hypothyroidism.

- Nephrotic syndrome. Commonly the first sign of nephrotic syndrome, periorbital edema precedes dependent and abdominal edema. Associated findings include weight gain, nausea, anorexia, lethargy, fatigue, and pallor.

- Orbital cellulitis. The sudden onset of periorbital edema marks orbital cellulitis. It may be accompanied by a unilateral purulent discharge, hyperemia, exophthalmos, conjunctival injection, impaired extraocular movements, a fever, and extreme orbital pain.

- Preeclampsia. Edema of the face, hands, and ankles is an early sign of preeclampsia. Other characteristics include excessive weight gain, a severe headache, blurred vision, hypertension, and midepigastric pain.

- Rhinitis (allergic). With rhinitis, red and edematous eyelids are accompanied by paroxysmal sneezing, itchy nose and eyes, and profuse, watery rhinorrhea. The patient may also develop nasal congestion, excessive tearing, a headache, sinus pain and, sometimes, malaise and a fever.

- Sinusitis. Frontal sinusitis causes edema of the forehead and eyelids. Maxillary sinusitis produces edema in the maxillary area as well as malaise, gingival swelling, and trismus. Both types are also accompanied by facial pain, a fever, nasal congestion, purulent nasal discharge, and red, swollen nasal mucosa.

- Superior vena cava syndrome. Superior vena cava syndrome gradually produces facial and neck edema accompanied by thoracic or jugular vein distention. It also causes central nervous system symptoms, such as a headache, vision disturbances, and vertigo.

- Trachoma. With trachoma, edema affects the eyelid and conjunctiva and is accompanied by eye pain, excessive tearing, photophobia, and eye discharge. Examination reveals an inflamed preauricular node and visible conjunctival follicles.

- Trichinosis. Trichinosis is a relatively rare infectious disorder that causes the sudden onset of eyelid edema with a fever (102°F to 104°F [38.9°C to 40°C]), conjunctivitis, muscle pain, itching and burning skin, sweating, skin lesions, and delirium.

Other Causes

- Diagnostic tests. An allergic reaction to contrast media used in radiologic tests may produce facial edema.

- Drugs. Long-term use of glucocorticoids may produce facial edema. Any drug that causes an allergic reaction (for example, aspirin, antipyretics, penicillin, and sulfa preparations) may have the same effect.

- Surgery and transfusion. Cranial, nasal, or jaw surgery may cause facial edema, as may a blood transfusion that causes an allergic reaction.

HERB ALERT

HERB ALERT

Ingestion of the fruit pulp of Ginkgo biloba can cause severe erythema and edema and the rapid formation of vesicles. Feverfew and Chrysanthemum parthenium can cause swelling of the lips, irritation of the tongue, and mouth ulcers. Licorice may cause facial edema and water retention or bloating, especially if used before menses.

Special Considerations

Administer an analgesic for pain, and apply cream to reduce itching. Unless contraindicated, apply cold compresses to the patient’s eyes to decrease edema. Elevate the head of the bed to help drain the accumulated fluid. Urine and blood tests are commonly ordered to help diagnose the cause of facial edema.

Patient Teaching

Explain the risks of delayed allergy symptoms and which signs and symptoms to report. Discuss ways to avoid allergens and insect bites or stings. Emphasize the importance of having an anaphylaxis kit and medical identification bracelet.

Pediatric Pointers

Normally, periorbital tissue pressure is lower in children than in adults. As a result, children are more likely to develop periorbital edema. In fact, periorbital edema is more common than peripheral edema in children with such disorders as heart failure and acute glomerulonephritis. Pertussis may also cause periorbital edema.

REFERENCES

El-Domyati, M., El-Ammawi, T. S., Medhat, W., Moawad, O., Brennan, D., Mahoney, M. G., & Uitto, J. (2011). Radiofrequency facial rejuvenation: Evidence-based effect. Journal of American Academy of Dermatology, 64(3), 524–535.

Knaggs, H. (2009). A new source of aging? Cosmetology Dermatology, 8(2), 77–82.

Edema of the Leg

Leg edema is a common sign that results when excess interstitial fluid accumulates in one or both legs. It may affect just the foot and ankle or extend to the thigh, and may be slight or dramatic, pitting or nonpitting.

Leg edema may result from venous disorders, trauma, and certain bone and cardiac disorders that disturb normal fluid balance. (See Understanding Fluid Balance, page 278.) It may result from nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, acute and chronic thrombophlebitis, chronic venous insufficiency (most common), cellulitis, lymphedema, and drugs. However, several nonpathologic mechanisms may also cause leg edema. For example, prolonged sitting, standing, or immobility may cause bilateral orthostatic edema. This pitting edema usually affects the foot and disappears with rest and leg elevation. Increased venous pressure late in pregnancy may cause ankle edema. Constricting garters or pantyhose may mechanically cause lower extremity edema.

History and Physical Examination

To evaluate the patient, first ask how long he has had the edema. Did it develop suddenly or gradually? Does it decrease if he elevates his legs? Is it painful when touched or when he walks? Is it worse in the morning, or does it get progressively worse during the day? Ask about a recent leg injury or recent surgery or illness that may have immobilized the patient. Does he have a history of cardiovascular disease? Finally, obtain a drug history.

Begin the physical examination by examining each leg for pitting edema. (See Edema: Pitting or Nonpitting? page 279.) Because leg edema may compromise arterial blood flow, palpate or use a Doppler to auscultate peripheral pulses to detect an insufficiency. Observe leg color and look for unusual vein patterns. Then palpate for warmth, tenderness, and cords, and gently squeeze the calf muscle against the tibia to check for deep pain. If leg edema is unilateral, dorsiflex the foot to look for Homans’ sign, which is indicated by calf pain. Finally, note skin thickening or ulceration in edematous areas.

Medical Causes

- Burns. Two days or less after injury, leg burns may cause mild to severe edema, pain, and tissue damage.

- Cellulitis. Pitting edema and orange peel skin are caused by a streptococcal or staphylococcal infection that most commonly occurs in the lower extremities. Cellulitis is also associated with erythema, warmth, and tenderness in the infected area.

- Envenomation. Mild to severe localized edema may develop suddenly at the site of a bite or sting, along with erythema, pain, urticaria, pruritus, and a burning sensation.

- Heart failure. Bilateral leg edema is an early sign of right-sided heart failure. Other signs and symptoms include weight gain despite anorexia, nausea, chest tightness, hypotension, pallor, tachypnea, exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, palpitations, a ventricular gallop, and inspiratory crackles. Pitting ankle edema, hepatomegaly, hemoptysis, and cyanosis signal more advanced heart failure.

- Leg trauma. Mild to severe localized edema may form around the trauma site.

- Osteomyelitis. When osteomyelitis — a bone infection — affects the lower leg, it usually produces localized, mild to moderate edema, which may spread to the adjacent joint. Edema typically follows a fever, localized tenderness, and pain that increases with leg movement.

- Thrombophlebitis. Deep and superficial vein thrombosis may cause unilateral mild to moderate edema. Deep vein thrombophlebitis may be asymptomatic or may cause mild to severe pain, warmth, and cyanosis in the affected leg, as well as a fever, chills, and malaise. Superficial thrombophlebitis typically causes pain, warmth, redness, tenderness, and induration along the affected vein.

- Venous insufficiency (chronic). Moderate to severe, unilateral or bilateral leg edema occurs in patients with venous insufficiency. Initially, the edema is soft and pitting; later, it becomes hard as tissues thicken. Other signs include darkened skin and painless, easily infected stasis ulcers around the ankle. Venous insufficiency generally occurs in females.

Other Causes

- Diagnostic tests. Venography is a rare cause of leg edema.

- Coronary artery bypass surgery. Unilateral venous insufficiency may follow saphenous vein retrieval.

Special Considerations

Provide an analgesic and antibiotic as needed. Have the patient avoid prolonged sitting or standing, elevate his legs as necessary, and instruct him not to cross his legs. A compression boot (Unna’s boot) may be used to help reduce edema. Monitor the patient’s intake and output, and check his weight and leg circumference daily to detect any change in the edema. Prepare him for diagnostic tests, such as blood and urine studies and X-rays. Determine the need for dietary modifications such as water and sodium restrictions. Monitor the affected extremity for skin breakdown.

Patient Counseling

Teach the proper application of antiembolism stockings or bandages. Instruct the patient in appropriate leg exercises. Explain the foods or fluids the patient should avoid.

Pediatric Pointers

Uncommon in children, leg edema may result from osteomyelitis, leg trauma, or, rarely, heart failure. Nephrotic syndrome results in bilateral leg edema, polyuria, and eyelid swelling.

REFERENCES

Bennell, K. L., & Hinman, R. S. (2012). A review of the clinical evidence for exercise in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Journal of Science in Medicine and Sport, 14, 4–9.

American Diabetes Association. (2012). Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care, 35, S64–S71.

Enuresis

Enuresis usually refers to nighttime urinary incontinence in girls age 5 and older and boys age 6 and older. Approximately 5 to 7 million children wet the bed. This sign rarely continues into adulthood, but may occur in some adults with sleep apnea. It’s most common in boys and may be classified as primary or secondary. Primary enuresis describes a child who has never achieved bladder control; secondary enuresis describes a child who achieved bladder control for at least 3 months but has lost it.

Among factors that may contribute to enuresis are delayed development of detrusor muscle control, unusually deep or sound sleep, organic disorders (such as a urinary tract infection [UTI] or obstruction), and psychological stress. Psychological stress, probably the most important factor, commonly results from the birth of a sibling, the death of a parent or loved one, divorce, or premature, rigorous toilet training. The child may be too embarrassed or ashamed to discuss his bed-wetting, which intensifies psychological stress and makes enuresis more likely — thus creating a vicious circle.

History and Physical Examination

When taking a history, include the parents as well as the child. First, determine the number of nights each week or month that the child wets the bed. Is there a family history of enuresis? Ask about the child’s daily fluid intake. Is there a history of daytime frequency, urgency, or incontinence? Does he drink much after supper? What are his typical sleep and voiding patterns? Ask if he has any bowel problems, such as constipation or encopresis. Find out if the child has ever had control of his bladder. If so, try to pinpoint what may have precipitated enuresis, such as an organic disorder or psychological stress. Does the bed-wetting occur at home and away from home? Ask the parents how they’ve tried to manage the problem, and have them describe the child’s toilet training. Observe the child’s and parents’ attitudes toward bed-wetting. Finally, ask the child if it hurts when he urinates.

Next, perform a physical examination to detect signs of neurologic or urinary tract disorders. Observe the child’s gait to check for motor dysfunction, and test sensory function in the legs. Inspect the urethral meatus for erythema, and obtain a urine specimen. A rectal examination to evaluate sphincter control may be required.

Medical Causes

- Detrusor muscle hyperactivity. Involuntary detrusor muscle contractions may cause primary or secondary enuresis associated with urinary urgency, frequency, and incontinence. Signs and symptoms of a UTI are also common.

- Diabetes. Enuresis may be one of the earliest signs of diabetes (type 1) in a child who normally doesn’t wet the bed. Other classic signs of diabetes that may present include increased thirst, increased hunger, urinating large amounts per void, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and unexplained weight loss.

- Urinary tract obstruction. Although daytime incontinence is more common, urinary tract obstruction may produce primary or secondary enuresis. It may also cause flank and lower back pain; upper abdominal distention; urinary frequency, urgency, hesitancy, and dribbling; dysuria; a diminished urine stream; hematuria; and variable urine output.

- UTI. In children, most UTIs produce secondary enuresis. Associated features include urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, straining to urinate, and hematuria. Lower back pain, fatigue, and suprapubic discomfort may also occur.

Special Considerations

If the child has detrusor muscle hyperactivity, bladder training may help control enuresis. An alarm device may be useful for children ages 8 and older. This moisture-sensitive device fits in his mattress and triggers an alarm when made wet, waking the child. This device conditions him to avoid bed-wetting and should be used only in cases in which enuresis is having adverse psychological effects on the child. Limit the child’s fluid intake 2 to 3 hours before bedtime. Pharmacologic treatment with desmopressin or an anticholinergic may be helpful.

Patient Counseling

Provide emotional support to the child and his family. Encourage the parents to accept and support the child. Explain any underlying causes of the enuresis and its treatment, and teach the parents how to manage enuresis at home.

REFERENCES

Kwak, K. W., Lee, Y. S., Park, K. H., & Baek, M. (2010). Efficacy of desmopressin and enuresis alarm as first and second line treatment for primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: Prospective randomized crossover study. Journal of Urology, 184(6), 2521–2526.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2011). Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: A guide to best practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Epistaxis

A common sign, epistaxis (nosebleed) can be spontaneous or induced from the front or back of the nose. Most nosebleeds occur in the anterior-inferior nasal septum (Kiesselbach’s plexus), but they may also occur at the point where the inferior turbinates meet the nasopharynx. Usually unilateral, they seem bilateral when blood runs from the bleeding side behind the nasal septum and out the opposite side. Epistaxis ranges from mild oozing to severe — possibly life-threatening — blood loss.

A rich supply of fragile blood vessels makes the nose particularly vulnerable to bleeding. Air moving through the nose can dry and irritate the mucous membranes, forming crusts that bleed when they’re removed; dry mucous membranes are also more susceptible to infection, which can produce epistaxis as well. Trauma is another common cause of epistaxis. Additional causes include septal deviations; hematologic, coagulation, renal, and GI disorders; and certain drugs and treatments.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has severe epistaxis, quickly take his vital signs. Be alert for tachypnea, hypotension, and other signs of hypovolemic shock. Insert a large-gauge I.V. line for rapid fluid and blood replacement, and attempt to control bleeding by pinching the nares closed. (However, if you suspect a nasal fracture, don’t pinch the nares. Instead, place gauze under the patient’s nose to absorb the blood.)

Have a hypovolemic patient lie down and turn his head to the side to prevent blood from draining down the back of his throat, which could cause aspiration or vomiting of swallowed blood. If the patient isn’t hypovolemic, have him sit upright and tilt his head forward. Constantly check airway patency. If the patient’s condition is unstable, begin cardiac monitoring and give supplemental oxygen by mask.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree