Chapter Twenty

Drug Information and Contemporary Community Pharmacy Practice

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

• Discuss limitations of the current approaches pharmacists use to deliver drug information to their patients.

• Compare and contrast patient education and consumer health information (CHI) as drug information sources for patients.

• Define Web 2.0 and social networking and describe how patients use these tools as a drug information source.

• Discuss mobile health information technology and its impact on how consumers are obtaining information.

• Describe the model for drug information services delivered by community pharmacists.

• Design three strategies using electronic media to assist patients in receiving and applying high-quality drug information.

• List seven characteristics of a high-quality health literate Internet site.

• Define information therapy in the context of a pharmacist delivered drug information service.

![]()

Key Concepts

Introduction

Pharmacists’ roles and responsibilities continue to evolve in response to changing pharmacy practice acts and a dynamic health care environment. One constant is the pharmacist’s key function as a provider of quality, evidence-based drug information. However, pharmacists are not the only source of drug information. The Internet has made information from sources other than health professionals more readily available and Web sites devoted to health information are accessible to anyone on the Web. The move toward patient-centered care and consumerism increases the desire for patients to be in control of their health care and be an active part of the decision-making process. ![]() The trend for patients to obtain their health information from sources disconnected from health care professionals is not going away and it has shifted relationships between patients and their traditional touchstones in health care, namely physicians, nurses, and pharmacists.1 Recent surveys suggest 60% to 80% of American consumers use the Internet to search for some type of health or wellness information.2 The pharmacist’s role as drug information expert may also be changing in the eyes of the patient. In 2010, 29% of patients reported not using health care professionals, including pharmacists, as a source to locate or access health information.2

The trend for patients to obtain their health information from sources disconnected from health care professionals is not going away and it has shifted relationships between patients and their traditional touchstones in health care, namely physicians, nurses, and pharmacists.1 Recent surveys suggest 60% to 80% of American consumers use the Internet to search for some type of health or wellness information.2 The pharmacist’s role as drug information expert may also be changing in the eyes of the patient. In 2010, 29% of patients reported not using health care professionals, including pharmacists, as a source to locate or access health information.2

Pharmacy practice is moving away from its emphasis on the hands-on drug distribution model toward an emphasis on system management and patient care services.3,4 It is important for pharmacists to enhance patient care services because of significant expenditures seen with unresolved drug-related problems. Nonadherence to medication therapy was estimated to cost $300 billion annually in direct and indirect costs in 2011 by the National Council on Patient Information and Education.5 A key strategy to improve adherence is to improve patients’ understanding of their disease and its management and include their needs in the treatment planning. Both strategies require individualized care that is not available from the World Wide Web and other information sources. Pharmacists can remain a valuable drug information source for patients because they are one of the most accessible health care practitioners. Pharmacists can help patients customize information they find on the Internet and from other such sources. The danger right now for pharmacists is that if they do not step up and add drug information services beyond what a patient can find on their own, as well as develop patient demand for these services, they will become less relevant. Project Destiny, an initiative between the National Association of Chain Drug Stores (NACDS), American Pharmacists Association (APhA), and the National Community Pharmacists Association (NCPA) introduced in 2008, encourages pharmacists to “embrace community pharmacy health care beyond dispensing” and identifies a number of significant unmet needs for improved medication therapy management, including health product information and derivative services. Pharmacists are well positioned to address these needs as they are medication experts and trusted professionals. In this model, patients will view pharmacists as a key medication advisor. For example, patients see results from clinical research on the news or through the Internet. They may not understand how these results relate directly to them and may reconsider continuing their medication. Pharmacists, with their understanding of both the literature and the patient’s medical history, can help the patient understand whether these new findings are relevant to their individual situation.

According to a 2012 survey, 94% of patients select a specific pharmacy based on location and convenience. When price is not a factor, accuracy and trust provided by the pharmacists were cited as a reason for going to a pharmacy only 9% and 4% of the time, respectively. These results further support the need to develop consumer demand for patient care services.6 The purpose of this chapter is to shed light on how increased patient demand for autonomy and responsibility over their own health care and use of information sources beyond health professionals impacts community pharmacy. Additionally, new models for community pharmacists delivering drug information will be addressed.

Pharmacists as Drug Information Providers in the Community Setting

Pharmacists are required by Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA’90) to deliver patient counseling when they dispense a Medicaid prescription.7 Individual states can and sometimes do mandate that counseling be extended to all patients, irrespective of their insurance. Some pharmacists are very diligent in providing important information to their patients when they pick up a prescription, while others only give information if specifically asked. Patients may be asked by pharmacy staff to electronically sign to decline counseling without being asked whether they want it or not. Some patients do not even know what they are signing. ![]() Answering drug information questions is a routine part of a pharmacist’s day, but it is too often a passive process that hinges upon the patient’s initiative to ask the important questions regarding their health. A variety of reasons make patients reluctant to use their pharmacist as a primary health information resource. Although the most accessible health care professional to patients, pharmacists often may appear too busy and unavailable within the sometimes hectic pharmacy. Technicians or cashiers may be the only staff who speaks directly to the patient. Simply asking whether or not a patient has questions is the wrong way to initiate counseling. Patients may not be sure what they need to know in the first place, or feel embarrassed or ashamed to admit their lack of knowledge. In some cases, patients are unaware they should be asking questions. Some simply do not understand the importance of pharmacotherapy to their long-term health and well-being and are not vested in learning about the appropriate medication use.

Answering drug information questions is a routine part of a pharmacist’s day, but it is too often a passive process that hinges upon the patient’s initiative to ask the important questions regarding their health. A variety of reasons make patients reluctant to use their pharmacist as a primary health information resource. Although the most accessible health care professional to patients, pharmacists often may appear too busy and unavailable within the sometimes hectic pharmacy. Technicians or cashiers may be the only staff who speaks directly to the patient. Simply asking whether or not a patient has questions is the wrong way to initiate counseling. Patients may not be sure what they need to know in the first place, or feel embarrassed or ashamed to admit their lack of knowledge. In some cases, patients are unaware they should be asking questions. Some simply do not understand the importance of pharmacotherapy to their long-term health and well-being and are not vested in learning about the appropriate medication use.

Patient leaflets are just one example why patients may not seek out their pharmacist as a primary health information resource. Instead of direct patient communication, patient leaflets are commonly stapled to the prescription as a substitute for actual patient education. In fact, a survey of community pharmacies found that while 89% of patients received leaflets from their pharmacy, only 5% were given verbal explanation along with it and only 8% of the time did the pharmacist emphasize the important content found within the leaflet.8 Sixty-six percent of patients were given the document without any further information at all, making it hard for them to establish key points to be taken away from the leaflet. Additionally, many of these leaflets do not adhere to the qualities of good health literacy, making them hard for patients to use as a source of health information. Additional information on the importance of good health literacy will be discussed later in the chapter.

Some pharmacies have developed Web sites to direct patients to quality drug information and offer an additional path for patients to ask questions. Many large chain pharmacies and mail-order pharmacies have begun to post answers to the most frequently asked drug information questions for their consumers on their Web sites and some allow for even more interaction online by giving patients the opportunity to ask their questions to a pharmacist. In addition, these Web sites also provide general information regarding medications in the form of patient leaflets. It is important to note that while these pharmacies are headed in the right direction in terms of giving patients more readily available access to quality health information online; these Web sites still have many limitations. Patients enrolled in disease state management and medication therapy management (MTM) programs require the pharmacist to be engaged in focused and directed patient education as part of a comprehensive treatment plan; something that cannot be done by passive answering of questions or interfacing with a Web site alone.

Current Patient Sources of Drug Information

The practice of drug information continues to evolve along with the profession. Drug information can be as simple as obtaining information from references, or an interactive experience between a specific patient and the pharmacist.9 Drug information can be as active as counseling a patient on all of his or her medications and disease states or as passive as a pharmacy technician dispensing a medication leaflet with a prescription. Regardless of how drug information is delivered, patients are in need of a more connected experience when receiving drug information, not only from health care professionals, but also from peers.

PATIENT EDUCATION VERSUS CONSUMER HEALTH INFORMATION

Patient education and consumer health information (CHI) are two distinct ways patients get information about medications, although the two may merge when pharmacists truly engage their patients. ![]() Patient education delivers written or verbal drug information through a planned activity initiated by a health care provider. The goal is to change patient behavior, improve adherence, and ultimately improve health.10 Pharmacist-driven patient education formats include brief counseling when a patient picks up their medication, more comprehensive education as a part of medication therapy management, point-of-care testing (e.g., blood glucose or cholesterol testing), and health screenings. Patient education can be delivered face-to-face or through a variety of technologies, including the telephone, e-mail, and Webcams. The key is that pharmacists interact with individual patients to customize the information to their specific situation.

Patient education delivers written or verbal drug information through a planned activity initiated by a health care provider. The goal is to change patient behavior, improve adherence, and ultimately improve health.10 Pharmacist-driven patient education formats include brief counseling when a patient picks up their medication, more comprehensive education as a part of medication therapy management, point-of-care testing (e.g., blood glucose or cholesterol testing), and health screenings. Patient education can be delivered face-to-face or through a variety of technologies, including the telephone, e-mail, and Webcams. The key is that pharmacists interact with individual patients to customize the information to their specific situation.

![]() CHI is actively sought by the patient in response to their need for more information about their health. Importantly, CHI is not individualized for a specific patient. Unlike patient education, which is initiated by the pharmacist, CHI is completely patient driven and has evolved out of the patient’s need to be their own advocate. CHI has long been available to patients, but the Internet accelerated both the access to and the volume of information; the choices are endless for patients seeking their own information. In 2011, searching for health information online became the third most common activity among Internet users.11

CHI is actively sought by the patient in response to their need for more information about their health. Importantly, CHI is not individualized for a specific patient. Unlike patient education, which is initiated by the pharmacist, CHI is completely patient driven and has evolved out of the patient’s need to be their own advocate. CHI has long been available to patients, but the Internet accelerated both the access to and the volume of information; the choices are endless for patients seeking their own information. In 2011, searching for health information online became the third most common activity among Internet users.11

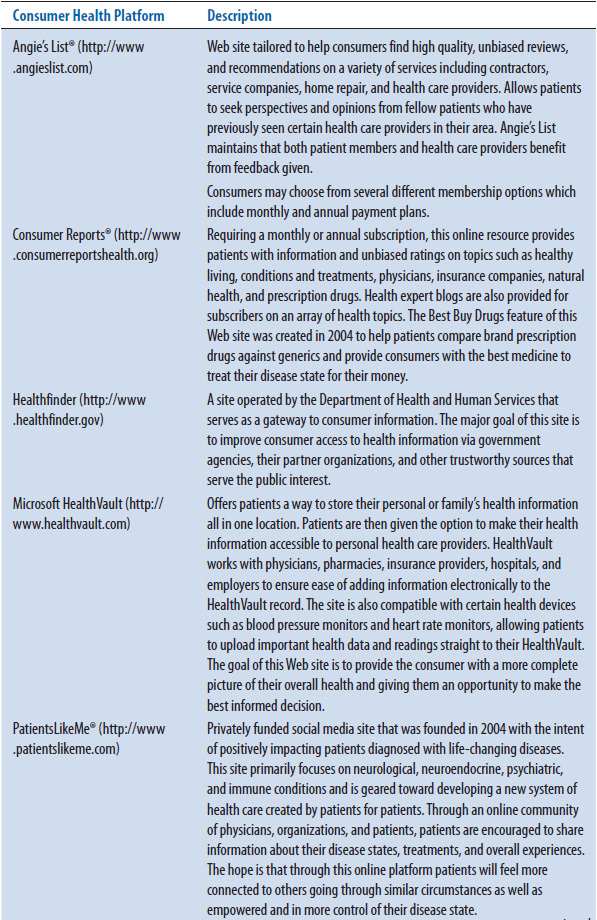

For either patient education or CHI to be of any value to the patient, it is crucial that evidence presented to the patient be of high quality and strength. Controlling quality during a patient education encounter is easier because the health care professional filters information distributed to patients. In contrast, the quality and reliability of consumer health information is variable.12 CHI may be of excellent quality and beneficial to the patient, or it may be of high quality but dangerous because it lacks relevance to their situation, be incomplete, or simply be wrong. Table 20–1 lists examples of popular consumer health information sites.

TABLE 20–1. EXAMPLES OF POPULAR CONSUMER HEALTH INFORMATION AND SOCIAL MEDIA SITES13–19

SOCIAL MEDIA—A NEW FORM OF CONSUMER HEALTH INFORMATION

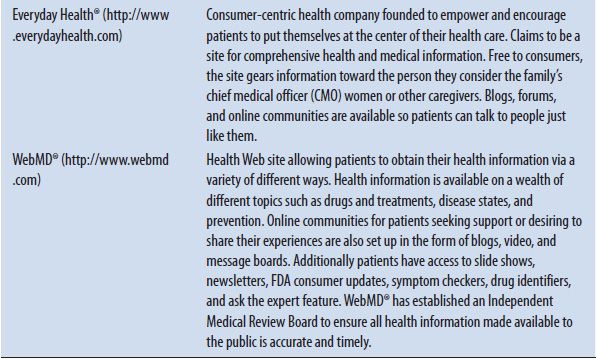

Patients have long used friends, family, coworkers, and support groups as sources of medical information. The Internet adds to these traditional sources through social media, as described in Table 20–2.1 ![]() Social media sites allow patients to create content and share information about their health on the Internet. Web 2.0 is an important concept in understanding the power of the social media. Web 2.0 is not new software but a different strategy to use the Web. The Web goes beyond being a search engine and a source of information to include a platform to create, share, and collaborate in developing new knowledge. Social networking is the phenomenon of online communities in which people share interests and/or activities with one another and is an outgrowth of Web 2.0. With respect to CHI, patients no longer just read about their health information online, but can have an active role controlling content, creating new information, and sharing their experiences with others. For example, PatientsLikeMe® (http://www.patientslikeme.com/) is a privately funded company founded in 2004 with the purpose of creating a community of patients with neurological, neuroendocrine, psychiatric, and immune conditions. Site content is posted by actual patients and includes what treatments they have tried, what works and what does not work for them, and what side effects they experience. Discussions often include the quality of the care delivered by their providers.

Social media sites allow patients to create content and share information about their health on the Internet. Web 2.0 is an important concept in understanding the power of the social media. Web 2.0 is not new software but a different strategy to use the Web. The Web goes beyond being a search engine and a source of information to include a platform to create, share, and collaborate in developing new knowledge. Social networking is the phenomenon of online communities in which people share interests and/or activities with one another and is an outgrowth of Web 2.0. With respect to CHI, patients no longer just read about their health information online, but can have an active role controlling content, creating new information, and sharing their experiences with others. For example, PatientsLikeMe® (http://www.patientslikeme.com/) is a privately funded company founded in 2004 with the purpose of creating a community of patients with neurological, neuroendocrine, psychiatric, and immune conditions. Site content is posted by actual patients and includes what treatments they have tried, what works and what does not work for them, and what side effects they experience. Discussions often include the quality of the care delivered by their providers.

TABLE 20–2. SOCIAL MEDIA DEFINITIONS AND PLATFORMS USED TO OBTAIN HEALTH INFORMATION1

![]() Wisdom of crowds is a belief that when patients share information about their common conditions through social networking, their collective wisdom is more beneficial than the expert opinion of just one individual. Patients do not completely resist the advice of health professionals, but are just not as willing to rely on a single expert opinion for their information.1 Health information received via social media is greatly valued by many consumers, especially the “net generation” as described by Don Tapscott in Grown Up Digital.20 This “net generation” made up of consumers born in the early 1980s or after, have grown up online and prefer to engage and collaborate via technology. Extremely used to the digital world, they often trust a search engine on the Internet to provide answers or an online peer review over an expert. Opinions, stories, successes and failures, treatment options, and adverse effects are just some of what this “net generation” of patients share in the social media. This feeling of camaraderie and support obtained via networks is something patients feel they cannot attain from most health care professionals. Some patients may even have reservations when it comes to trusting their health care professional. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer conducted in 2012, people are inclined more than ever to trust social media (consists of social networking sites, content-sharing sites, and blogs) as a source for information.21 In fact, one in five adult Internet users state they have gone online to connect with other people who have health conditions similar to themselves.22 The concern is that posts made by patients are a reflection of their unique experience and may be incorrect or inappropriate for another individual. It is imperative patients keep in mind the wealth of information retrieved from peers should be used only to supplement the wealth of information provided by practitioners and that the Internet does not replace health care professionals.22

Wisdom of crowds is a belief that when patients share information about their common conditions through social networking, their collective wisdom is more beneficial than the expert opinion of just one individual. Patients do not completely resist the advice of health professionals, but are just not as willing to rely on a single expert opinion for their information.1 Health information received via social media is greatly valued by many consumers, especially the “net generation” as described by Don Tapscott in Grown Up Digital.20 This “net generation” made up of consumers born in the early 1980s or after, have grown up online and prefer to engage and collaborate via technology. Extremely used to the digital world, they often trust a search engine on the Internet to provide answers or an online peer review over an expert. Opinions, stories, successes and failures, treatment options, and adverse effects are just some of what this “net generation” of patients share in the social media. This feeling of camaraderie and support obtained via networks is something patients feel they cannot attain from most health care professionals. Some patients may even have reservations when it comes to trusting their health care professional. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer conducted in 2012, people are inclined more than ever to trust social media (consists of social networking sites, content-sharing sites, and blogs) as a source for information.21 In fact, one in five adult Internet users state they have gone online to connect with other people who have health conditions similar to themselves.22 The concern is that posts made by patients are a reflection of their unique experience and may be incorrect or inappropriate for another individual. It is imperative patients keep in mind the wealth of information retrieved from peers should be used only to supplement the wealth of information provided by practitioners and that the Internet does not replace health care professionals.22

Most social media outlets that give consumers the ability to post opinions, recommendations, and health information state that they are not a substitute for advice of a qualified health professional. While the provision of these disclaimers can be a sign of a quality site, unfortunately, they are not always posted in the most visible place for many consumers on these Web sites, nor do consumers often heed these disclaimers’ warning.

Case Study 20–1

You are the only pharmacist on duty at a local community pharmacy. You are short staffed, the phone is ringing, and you have 50+ prescriptions yet to verify. You are doing your best to make the wait as short as possible. In the midst of all this, one of your regular patients comes up to the counter and announces that she will no longer be taking her antidepressant. She describes how lately she has been feeling strange and feels fairly certain it is due to the antidepressant. She then explains to you how she has recently gone online to find more information about the specific medication she is taking. “You wouldn’t believe all the good information that is out there,” she says, “I was able to talk to other patients and they were so helpful!” She then goes on to talk about the many patient testimonials she read telling her to discontinue her medication.

The patient seems adamant that she is going to stop taking her antidepressant. As a pharmacist, this concerns you. The pharmacy technician calls you to resume verifying prescriptions because the pharmacy is quickly getting out of control.

• Do you take the time to counsel this patient or do you get back to filling prescriptions before patients start complaining about the wait time?

• If you decide to counsel this patient, how would you educate her on the appropriate use of online resources to find health information?

• After counseling your patient, she still is determined to stop her antidepressant. What is the most important advice you can give her at this point?

![]()

MOBILE HEALTH—THE DAWN OF THE SMARTPHONE AND OTHER MOBILE DEVICES

Cell phones have made obtaining health information via mobile software applications that much easier. In 2012, a total of 85% of U.S. adults carry a cell phone,23 31% of which have accessed health information with their cell phones, a statistic that has increased 14% from 2010. Of the 85% of cell phone users, 53% of these are a smartphone user, which means retrieving health information is as simple as the touch of a fingertip. One in five smartphone owners report downloading at least one health application software (apps) to their phone, with exercise, weight, and diet applications being among the most popular. According to ABI research, by 2016 the market for mobile health apps is predicted to quadruple to $400 million with worldwide sales of smartphones anticipated to hit 1.5 billion units.24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree