Drainage Procedures: Pyloromyotomy, Pyloroplasty, Gastrojejunostomy

George A. Sarosi Jr.

DEFINITION

Drainage procedures, or more properly gastric drainage procedures, are a variety of surgical approaches used to either render incompetent or bypass the pylorus. Drainage procedures are often performed in conjunction with procedures that interrupt vagal innervation of the pylorus, and the purpose is to facilitate gastric drainage. Originally performed in conjunction with a truncal vagotomy for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease, drainage procedures are also performed to facilitate gastric emptying when the stomach is used as an esophageal replacement and occasionally to address poor gastric emptying in patients who have undergone fundoplication or paraesophageal hernia repair. Gastrojejunostomy is also frequently used to treat duodenal or gastric outlet obstruction.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In patients who have undergone prior gastroesophageal (GE) junction surgery, the differential diagnosis for abdominal bloating includes visceral hypersensitivity (irritable bowel syndrome [IBS]), gastroparesis, postsurgical delayed gastric emptying secondary to vagal injury, paraesophageal herniation of the fundoplication or portions of the stomach, and overeating or excess consumption of inappropriate foods such as carbonated beverages.

In patients who have undergone esophageal replacement with a gastric conduit, the differential diagnosis of dysphagia, early satiety, or regurgitation of undigested foods includes anastomotic structure, an inadequate-sized hiatal opening, torsion of the conduit, paraesophageal hernia, and competent pylorus.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Depending on the indication for a drainage procedure, certain historical elements and physical findings should be sought.

For patients with peptic ulcer disease, the duration of symptoms and any prior treatment of peptic ulcer disease should be sought. In addition, knowledge of the patients’ Helicobacter pylori status and prior H. pylori treatment is important. Finally, a history of use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or aspirin products should be sought.

In patients with a prior history of peptic ulcer disease who are undergoing surgical treatment of a bleeding ulcer, a history of prior ulcer disease should alert the surgeon to the possibility of encountering a scarred and possibly fibrotic duodenum.

Patients known to be H. pylori positive who have not had treatment for their H. pylori may not require an acid-reducing procedure at the time of surgical bleeding control. Simple ligation of the bleeding site may be sufficient.

Patients with a significant history of NSAID or aspirin product use are at a significant risk of recurrent ulcers and must be counseled to avoid all these products in the future.

For patients undergoing drainage procedures after esophageal replacement with a gastric conduit, patients should be questioned carefully about their symptoms. Patients with poor gastric drainage will describe early satiety, bloating, regurgitation, or emesis of undigested food. Patients with anastomotic strictures typically will describe dysphagia.

For patients undergoing or who have undergone a fundoplication, a history of postprandial abdominal pain, bloating, or early satiety should be sought, as this can be a symptom of poor gastric emptying, which can be confirmed with a gastric emptying study.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

In patients undergoing emergency operations for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, all patients should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) prior to operation with an attempt at endoscopic hemostasis. The operating surgeon should make every effort to be present during the endoscopy, as accurate anatomic information regarding the location of the ulcer will facilitate the operation.

In patients suspected of having poor emptying of their gastric conduit after esophageal replacement, gastric emptying studies are of limited use due to the altered anatomy and the lack of reference values for emptying. The author has used EGD and botulinum toxin injection as a diagnostic test for patients with poor emptying of the conduit.1 Those who have an improvement in symptoms have been offered surgical drainage procedures.

In patients with prior fundoplication or paraesophageal hernia repair suspected of having delayed gastric emptying, nuclear medicine gastric emptying studies are helpful in identifying patients who could benefit from a drainage procedure. Hamrick et al.,2 in a large series of revisional paraesophageal hernia patients, used a T1/2 emptying time of 90 minutes as an indication for the addition of a gastric drainage procedure with good results. Alternatively, EGD and botulinum toxin injection of the pylorus can also be used as a diagnostic study.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Patients undergoing drainage procedures will have poor gastric emptying and will be at risk for aspiration during induction of anesthesia. For elective procedures, patients should be placed on a clear liquid diet 24 hours prior to surgery and made NPO the night before the procedure. Patients undergoing emergency surgery for peptic ulcer bleeding will have

a stomach full of blood and are at significant risk of aspiration. Whenever feasible, rapid sequence induction should be used. Antibiotic prophylaxis with 1 to 2 g of cefazolin is the standard approach; clindamycin plus a fluoroquinolone or aminoglycoside is the appropriate choice for those patients with allergies to cefazolin. When performing an emergency operation for bleeding, the surgeon should ensure that blood is crossmatched and available. For laparoscopic procedures, having the ability to perform intraoperative EGD can facilitate the identification of the pylorus and bleeding source in difficult cases.

Positioning

For open drainage procedures, the patient is positioned in the supine position with both arms extended. Space is left on the patient’s left side to attach a Buchwalter or Omni retractor to the bed rail. During the surgical procedure, the patient will often be placed in reverse Trendelenburg to facilitate exposure of the upper abdominal organs. In a laparoscopic approach, the same position is used, but a footboard and safety strap should also be added to prevent the patient from sliding when steep reverse Trendelenburg position is used.

TECHNIQUES

OPEN PYLOROPLASTY

Skin Incision and Retractor Positioning

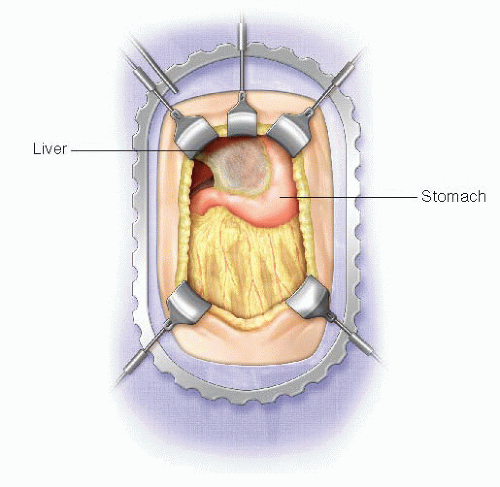

An upper midline incision is used for all open drainage procedures. This should begin at the level of the umbilicus and extend to just below the xiphoid process. Body wall retractor blades are placed on either side of the upper half of the incision to facilitate exposure. If necessary, a malleable or Harrington retractor blade can be placed on the left lobe of the liver to expose the pylorus (FIG 1).

Kocher Maneuver

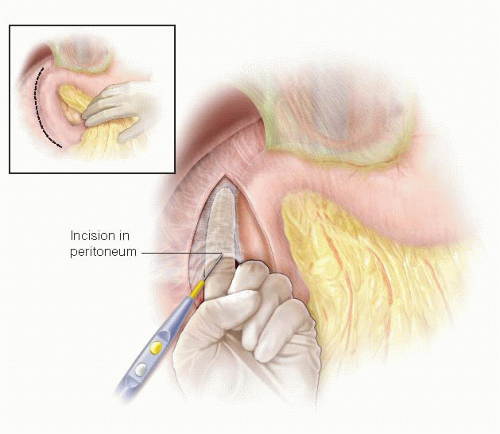

A Kocher maneuver is performed to facilitate exposure of the duodenum and pylorus and to eliminate tension on the suture line. A forceps is used to grasp the peritoneum lateral to the duodenum, which is then incised with scissors or the electrosurgical device. The surgeon then can insert an index finger behind the duodenum and head of the pancreas and sweep the finger to the right, elevating the lateral duodenal ligament and avascular retroperitoneal tissues, which can then be divided with the electrosurgical device (FIG 2). The plane of dissection should remain close to the duodenal wall to avoid injury to the gonadal vein on the anterior surface of the inferior vena cava. The duodenum and head of the pancreas should be mobilized from the junction of the duodenal bulb and second portion of the duodenum to just before the lateral aspect of the superior mesenteric vein. If the procedure is being performed for a bleeding duodenal ulcer, the Kocher maneuver step can be deferred until after control of the bleeding vessel has been achieved.

Pyloric Incision

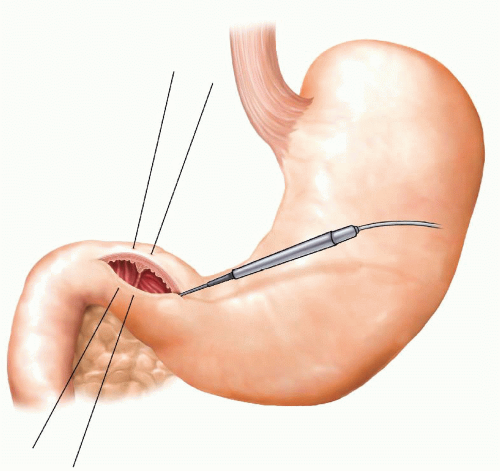

The pylorus is identified either visually or by palpation of the muscular ring with a finger inserted from the gastric side. Beginning roughly 2 cm proximal to the pylorus on the gastric antrum, incise the gastric wall, enter the lumen, and extend the incision distally parallel to the long axis of the bowel across the pylorus onto the duodenum to distance of roughly 5 cm using the electrosurgical device (FIG 3). This incision will provide reasonable exposure of the duodenal bulb. If the operation is being performed for ulcer bleeding, the incision can be extended further along the duodenum to expose the bleeding site. The pyloroplasty incision can be facilitated by placing a seromuscular stay stitch on the superior and inferior edge of the pylorus.

Bleeding Control

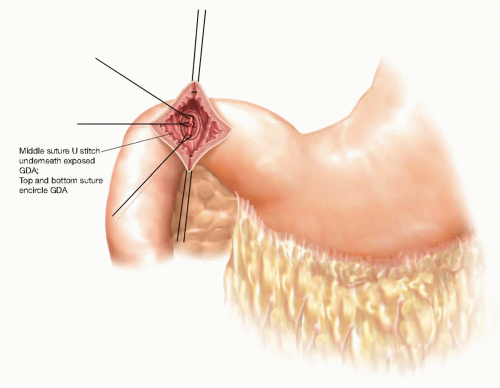

If the operation is being performed for a bleeding duodenal ulcer, the ulcer is identified on the posterior aspect of the duodenal bulb. Temporary hemostasis is achieved by digital pressure, and then definitive hemostasis is achieved by placing three 2-0 silk suture ligatures. The first suture is placed at the cranial margin of the ulcer, encircling the proximal gastroduodenal artery (GDA). The second suture is placed at the caudal edge of the duodenal ulcer encircling the distal GDA. The final suture is a U suture placed underneath the ulcer crater to control the posterior entry of the transverse pancreatic artery into the back wall of the GDA (FIG 4).

Closure of Pyloroplasty—Heineke-Mikulicz

The most common closure of the pyloroplasty is the Heineke-Mikulicz approach, closing the longitudinal pyloroplasty with a single layer of sutures in a transverse fashion. This closure is appropriate when the duodenum is not distorted or scarred and the pyloroplasty incision is shorter than 6 to 7 cm. The closure is performed by applying superior and inferior traction on the stay sutures, converting the longitudinal gastroduodenal incision into a transverse incision. The incision is then closed with interrupted 3-0 silk sutures or 3-0 polyglycolic acid sutures with either a full-thickness simple stitch or a Gambee stitch. The closure is best performed by starting at the top corner of the incision and alternating from the top to the bottom proceeding toward the middle. The sutures may be tied as they are placed until the last three sutures, which should be left untied until all of the sutures are placed to ensure that the mucosal layer is included in all of the bites (FIG 5). A vascularized pedicle of omentum is then placed over the closure and the stay sutures tied over the omental pedicle to hold it in place in the fashion of a Graham patch.

Closure of Pyloroplasty—Finney

If the duodenum is significantly inflamed or scarred from chronic peptic ulceration or if a longer duodenotomy is required to obtain hemostasis on a bleeding source beyond the duodenal bulb, a Finney closure of the pylorus is appropriate to prevent tension on the closure and gastric outlet obstruction. The Finney closure is in essence a side-to-side gastroduodenostomy with the pylorus at the cranial apex of the anastomosis. The duodenum will need to be completely mobilized to allow

this closure to be tension free. Remove the inferior stay suture and apply cranial tension on the superior stay suture to convert the longitudinal incision into an inverted U shape. The Finney closure is a standard two-layered anastomosis. A back row of interrupted 3-0 silk seromuscular (Lembert) sutures is placed between the inferior edge of the duodenum and the gastric wall (FIG 6A). These sutures should be placed 5 to 10 mm from the cut edge of the mucosa. It is often necessary to extend the incision on the gastric side of the pylorus to ensure that the lengths of the two arms of the incision are equal. When extending the pyloroplasty in this fashion, it is advisable to cheat toward the greater curvature of the stomach. Next, begin the inner layer of the closure using a 3-0 polyglycolic acid running suture beginning at the divided pylorus muscle, suturing the inferior edge of the duodenum to the inferior edge of the stomach (FIG 6B). Run this suture around the inferior edge of the closure onto the anterior edge of the gastroduodenal anastomosis. Next, begin a second running 3-0 polyglycolic acid at the superior edge of the cut pylorus, suturing the superior edge of the duodenum to the stomach and running toward the other suture (FIG 7A). Many surgeons prefer to use a Connell suture on the anterior wall to achieve better mucosal inversion. Tie the two sutures and then complete the pyloroplasty closure with an anterior layer of interrupted 3-0 silk seromuscular sutures (FIG 7B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree