Documentation

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• INTRODUCTION

Pharmacist documentation of patient encounters is an essential element of providing pharmaceutical care. There are several ways to document patient care activities in the patient medical record. Prior to 1970, free-flowing narrative was the predominant method of documentation. Its primary disadvantage was that it did not provide a mechanism for which multiple providers, who were involved in the care of a single patient, to effectively communicate with each other. The notes were organized differently by each provider and one had to read the entire note to get important information, and yet many times narrative notes would not contain critical information.

The second approach is the structured approach. In 1968, Lawrence Weed, the director of the family practice residency program at Western Reserve University, became frustrated with the difficulty and variety of ways residents approached the diagnosis and treatment of patients, many of whom had multiple health problems. Initially, he devised a logical, rational, problem-based method of thinking about a patient, which he called SOAP. S stands for Subjective or patient history. O stands for Objective, which includes diagnostic tests and physical examination. A stands for Assessment or diagnosis, and P stands for Plan, which includes treatment, education, and other logistical elements of the care plan. It provided a structure to the diagnostic process. As he implemented this logical approach with his residents, it grew into the problem-oriented medical record (POMR), using the SOAP format to document patient encounters by the patient’s health problems. The advantage of the POMR and SOAP approach is that they improve the quality of patient care through better communication between members of the health care team. In addition, use of the SOAP format guides the provider in a logical stepwise fashion to collect data, evaluate the patient’s problem, and develop a treatment plan. It also allows providers to more effectively follow patients’ progress and evaluate the efficacy of any interventions. In contrast to the narrative style, finding and reviewing patient notes with POMR are very rapid due to the organization of the note. Finally, in addition to improving quality and efficiency it serves a valuable purpose from a medicolegal standpoint. Organized, concise SOAP notes reduce the chances of misinterpretation and have been shown to have a positive impact on malpractice outcomes. Some variations of the POMR and SOAP are the predominant methods of documentation today, even in electronic health records, many of which have a SOAP template that drives writing a visit note. While this chapter teaches the process according to Weed’s original process, the reader should be aware that there are many variations in use today. DAP is data, assessment, and plan. HOAP is history, observation, assessment, and plan. SOAPIER adds intervention, evaluation, and revision. The exact format differs by institution and facility. Academic medical centers tend to use a more elaborate and comprehensive version due to its use in teaching health care providers, while private practitioners tend to use more concise notes.

• PROBLEM-ORIENTED MEDICAL RECORD SYSTEM

The POMR has two main components: the problem list and individual visit notes done using the SOAP format. The problem list serves as a dynamic table of contents with numbered problems and contains all of the patient’s significant active and inactive (past) health problems.

When reviewing a medical record to create a problem list, review each visit and record each new diagnosis for which the patient has been seen, along with the date of initial diagnosis. The next step is to distinguish between permanent problems that need to be put on the problem list and temporary problems that should not be placed on the problem list. Examples of permanent problems include chronic or recurring diseases such as diabetes or hypertension, past surgeries, adverse drug reactions, and vaccination status. The permanent problems are those that may impact current assessments. For example, a history of several C-sections 50 years ago (that caused scar tissue formation) may have an important influence when looking for causes in an 80-year-old woman presenting today with signs and symptoms consistent with intestinal obstruction.

Temporary problems are minor or self-limiting diseases, e.g., single episodes of acute otitis media, upper respiratory tract infection, sprained ankle, which will not have any impact on long-term health status. Temporary problems are not placed on the problem list. The problem list is a dynamic index to the medical record and changes as new information is added or evolves. For example, a single case of otitis media is a temporary problem. Six cases of AOM over 6 months become a permanent problem because now recurrent AOM may lead to serous otitis media, fluid buildup, and hearing loss or chronic suppurative otitis media due to the presence of a large central perforation. In those cases, we are going to consider many interventions to prevent hearing loss and slowed development of language skills such as prophylactic antibiotics, PE tubes, and tympanoplasty. This is now a permanent problem and it is a lifelong concern.

Once you have determined all the permanent problems, arrange them by date of initial diagnosis, oldest to newest, with the oldest permanent problem becoming problem number one. The remaining permanent problems are numbered in chronological order with the most recent diagnosis having the largest number. Some organizations will start with problem 00 and label it health maintenance, and use that to identify well-child visits, vaccinations, athletic physical examinations, and periodic preventive examinations as indicated by national standards, such as colonoscopies.

Finally, permanent problems must be separated into active and inactive. Active problems are those that the patient is currently being seen for or those that may have potential importance in the future. For example, if problem #1 was sulfa allergy, which represents the patient developing erythema multiforme to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 20 years ago, that is an active problem because providers will want to avoid using that antibiotic again and possibly other sulfa drugs such as thiazide diuretics or sulfonylureas. Resolved problems such as surgeries or completion of 9 months of isoniazid prophylaxis for a positive tuberculin skin test are not current worries. However, in the case involving multiple C-sections, that information may aid in a more rapid diagnosis of intestinal obstruction. Similarly in the patient who has completed INH prophylaxis, closer monitoring for reactivation of tuberculosis in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy or initiating use of immune suppressants such as ustekinumab would be warranted. Some institutions put the active and inactive problems in numerical sequence in separate columns, while others will make up two separate lists. The two-column approach can be seen in case 3.1 and is used in the exercises at the end of this chapter.

• SOAP NOTES

Labeling SOAP Notes

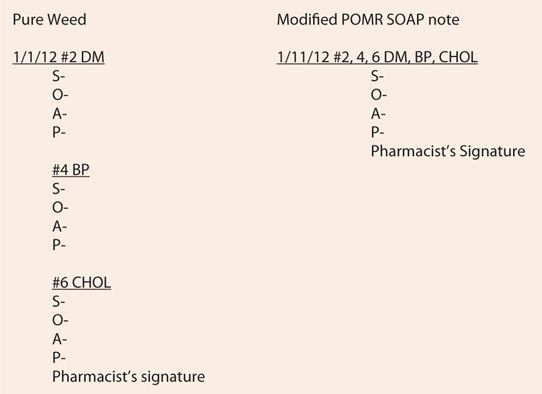

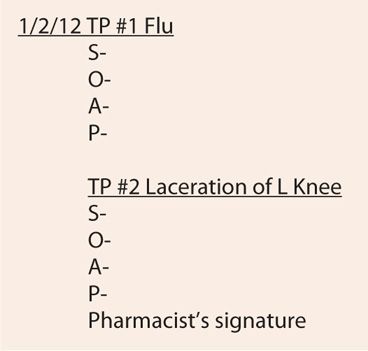

SOAP notes are always titled when documenting. This is to enable rapid perusal of the paper or electronic health record (EHR). Newer EHRs allow for search by diagnosis and problem number. For permanent problems, the title should include the problem number(s) and an abbreviation of the diagnosis. In a pure Weed system, each problem would have its own SOAP note, but over time physicians began to combine related disorders. So rather than having a SOAP note each for type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, many institutions allow physicians to combine related disorders. Temporary problems are titled as TP with the chief complaint serving as the title. If there are two chief complaints they are numbered consecutively. See Figures 3.1 and 3.2 for examples.

FIGURE 3.1 Titling entries for permanent problems.

FIGURE 3.2 Titling entries for temporary problems.

Signing the SOAP

Because encounter notes are medicolegal and quality assurance documents, they require the pharmacist’s signature. In a manual health record, the pharmacist will sign only once at the bottom of the note(s) for that day and include their degree so other providers can readily identify who saw the patient. Some states may also require pharmacist’s license numbers. In EHRs, entry into the record may automatically record the name, degree, and other requirements, others use a variety of checkboxes and codes, and others still require you to type in the appropriate information or will insert an electronic signature upon command. Regardless of the record format, all medical record entries require a provider’s signature.

SOAP

Subjective data S stands for subjective information, which is information obtained during their interview. It also includes information given to you verbally by family, friends, or other health care providers and staff. Subjective information is the patient’s and others’ perceptions of the illness. When answers to closed-ended questions rule out (r/o) complications due to chronic diseases, such as diabetes, all negative answers can be lumped under the term “denies,” e.g., “patient denies, visual disturbances, chest pain, shortness of breath (SOB), hypoglycemic symptoms, numbness and tingling in extremities, vaginal discharge, or dysuria.” Any positive responses are further investigated using LOQQSAM and added to the note. “She states she has periodic headaches that are mild, of short duration and are, relieved by acetaminophen and are not associated with low blood glucose or neurological symptoms.”

Objective Data O stands for objective data, which include laboratory or diagnostic test results, findings on physical examination, vital signs, and what you observe, e.g., labored breathing, splinting, or coughing, in addition to whatever is documented previously or found in the medical record by either yourself or other providers, including subjective information from previous visits, the problem list, etc.

Assessment A stands for assessment. Assessment includes the suspected diagnosis, level of control of chronic diseases, or provisional diagnosis while waiting for final confirmation of the diagnosis. For example, the 80-year-old lady with multiple C-sections might have her assessment read “Severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting r/o intestinal obstruction.” Later once the diagnosis is confirmed, it would change to intestinal obstruction. The degree of certainty in the diagnosis will be reflected in the problem list. In the case of a patient seen for a routine follow-up visit for diabetes, the entry might be “Type 2 diabetes nearly at target A1C, without complications.”

Plan P stands for plan, which includes a variety of topics. Referrals, follow-up appointments (“Return to clinic in 3 months.”), and further diagnostic tests are all included in the plan. In addition, the plan includes patient education performed and the treatment plan, which includes both drug and nondrug therapies. Students frequently ask where the pharmaceutical care plans go. The elements of pharmaceutical care plans, include most of the above things, and therefore, incorporating other elements of the care plan under P is appropriate.

• SUMMARY

Pharmacist documentation of clinical patient encounters is a required professional function. Structured documentation systems such as the POMR, along with its problem list and SOAP notes, are the most widely used of these structured approaches. Pharmacists should be able to develop a problem list by medical record review and to use SOAP notes to document each encounter.

DEVELOPING A PROBLEM LIST

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree