Distal Gastrectomy with Roux-En-Y Reconstruction

Miguel A. Mercado

History

In 1881, the same year he performed the first successful gastrectomy, Theodor Billroth performed the first gastroenterostomy. The continuity of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract was achieved by means of a gastroduodenostomy, later known as a Billroth I procedure. Four years later, the Viennese surgeon modified his technique and began using a latero-lateral anastomosis with the jejunum, later known as a Billroth II procedure.

The medical community soon began to report cases of postoperative bilious vomiting as the Billroth II became a more popular procedure. Hence, in 1897 a Swiss surgeon from Lausanne, César Roux, first described a gastrojejunostomy performed from a sectioned and defunctionalized jejunal loop with intestinal continuity established by means of a distal termino-lateral jejuno-jejunal anastomosis, the Roux-en-Y.

More than a century after its original description, the Roux-en-Y has evolved into an easier, safer, and quicker procedure and has become the preferred approach to reestablish continuity of the GI tract after distal gastrectomy (DG) in many centers.

Duodenal participation in the reestablishment of the GI tract is a theoretical advantage of the Billroth I procedure. A more physiological response to the passage of the bolus as well as a better absorption of calcium and iron are achieved with this operation. Nevertheless, several studies have shown that both short- and long-term results are similar when compared with other techniques. A delay in gastric emptying that is normally observed after bolus enters the duodenum, the so-called duodenal brake, is theoretically absent due to neural disruption as it would be for all other techniques mentioned.

As pyloric function is lost after resection, biliopancreatic reflux may cause severe symptoms due to direct irritation of the mucosa as well as increase the risk of cancer of the gastric remnant.

The anastomosis of the gastric remnant to a defunctionalized jejunal limb in a Roux-en-Y reduces biliopancreatic reflux and abolishes the afferent loop syndrome.

The main indication for DG in the previous century was peptic ulcer disease (prepyloric, pyloric, and postpyloric). Complete removal of the ulcer as well as most acid-producing parietal cells was accomplished with surgery. Today, with potent proton pump inhibitors as first-line therapy, surgery is reserved for complicated ulcers (penetrated and/or perforated, peptic stenosis, or bleeding refractory to both medical and endoscopic therapy).

The amount of stomach resected is an important issue when it comes to choosing the type of reconstruction. When antrectomy is performed a Billroth I can usually be accomplished without tension. Even when an ample Kocher maneuver has been done, when part of the corpus is removed it may be difficult to perform a Billroth I without tension in the gastroduodenal anastomosis. Recurrence of disease may also be a determinant factor when choosing the type of reconstruction especially when the duodenal stump is affected by disease or if a free margin is not obtained, in which case a Billroth I would not be optimal.

When the procedure of choice is a subtotal gastrectomy, the preferred reconstruction in most cases is a gastrojejunal anastomosis.

DG may also be indicated in early distal gastric cancer but is not recommended as standard treatment in locally advanced gastric cancer. In the latter, a formal gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy is the procedure of choice. Some cases with localized tumors can be treated with a subtotal gastric resection.

Other types of tumors can be adequately treated with a DG. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) originating from Cajal cells are a good example of such tumors. Leiomyomas and other rare benign tumors may also be treated with limited resections.

DG with latero-lateral gastrojejunostomy is also an intrinsic part of the classic Whipple procedure. The pylorus-preserving variant (PPPD) can also be done anastomosing the remnant of the first portion of the duodenum to the jejunal limb, distal to the pancreatic and bilioenteric anastomosis. Despite controversy, PPPD probably has a lower incidence of postoperative delayed gastric emptying and prevents biliopancreatic reflux to the stomach. Roux-en-Y reconstruction can safely be performed after pancreatoduodenectomy and is preferred by some groups. Detractors of the Roux often mention the additional entero-enteric anastomosis as a disadvantage.

Several recent trials aimed at determining the best reconstruction after DG, mostly comparing Roux-en-Y to one or both classic Billroth procedures, have been published.

In one recent series of 60 patients examined by Chan DC et al., Roux-en-Y reconstruction, classical Billroth II, and Billroth II plus distal entero-enterostomy (Braun) were compared. There was significant reduction of enterogastric reflux as well as lower incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in the Roux-en-Y group.

Csendes et al. reported a prospective, randomized study with long-term follow-up comparing Billroth II and Roux-en-Y reconstructions for the treatment of duodenal ulcers. With a follow-up of 12 to 21 years, they showed that Roux-en-Y is significantly better than traditional Billroth II reconstruction.

Another study was published by Kojima et al. except that DG was performed laparoscopically. Besides proving that laparoscopy is a feasible approach to such operations, the data also favored the Roux-en-Y.

Nunobe et al. analyzed the quality of life in the postoperative period in a large series of patients with early gastric cancer treated by subtotal gastrectomy. Subgroups of patients reconstructed by a Billroth I anastomosis and a Roux-en-Y were compared. There were fewer cases with dumping syndrome and endoscopically proven gastritis yet a higher incidence of cholelithiasis in the Roux-en-Y group. They therefore concluded that a Roux-en-Y was superior to Billroth I reconstruction.

A recently published review by Hoya et al. mentions possible disadvantages of Roux-en-Y reconstruction, including development of stomal ulcers, increased likelihood of cholelithiasis, difficulty during endoscopic approach to the ampulla and bile duct, and the so-called Roux stasis syndrome due to inadequate peristalsis of the jejunal limb. Detractors of the Roux-en-Y report delayed gastric emptying in the early postoperative period, the so-called Roux stasis syndrome, in 20% to 30% of patients although most patients respond with conservative measures. Modifications in the surgical technique have been advocated by some to reduce this complication.

Both the extent of gastrectomy and the addition of vagotomy (truncal or selective) affect the presence of stomal ulceration. Vagotomy is advisable when antrectomy is performed in order to prevent such ulcers. When the critical mass of parietal cells is greatly diminished, as in subtotal or total gastrectomy, the possibility of ulceration is low and there is no need for vagotomy.

In the vast majority of cases, all necessary information to plan surgery is gathered preoperatively with an upper GI endoscopy and a triphasic computed tomography (CT) scan.

Dehydration and electrolytic imbalances are common and must be corrected prior to surgery. Most patients should have an empty stomach with a 12-hour fast prior to surgery, yet patients with gastric outlet obstruction or gastroparesis may need considerably longer. Either ultrasound the day prior to surgery or gastric lavage through a nasogastric tube may be needed to confirm an empty stomach.

Prophylactic antibiotics are mandatory because of the high frequency of bacterial overgrowth in the retaining stomach and associated surgical site infections including complicated infections such as clostridial myositis.

Although an upper midline incision is preferred by most, other upper abdominal incisions may also be appropriate.

A routine inspection of the abdominal cavity is done and the procedure chosen depends on the location and extent of disease at laparotomy. Care must be taken to preserve all oncologic principles when the indication of surgery is early gastric cancer.

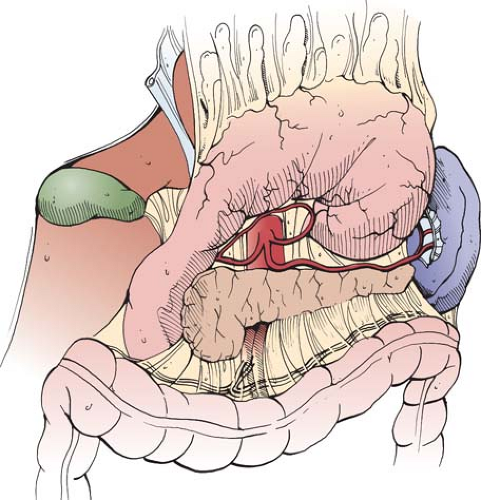

The greater omentum is included in the specimen when surgery is due to cancer, and it should be dissected close to its insertion in the transverse colon with electrocautery, a diathermy system (LigaSure®), or an ultrasonic scalpel (Fig. 1). Otherwise the greater omentum is divided from the middle of the gastrocolic ligament toward the left just distal to the gastroepiploic vessels. The left gastroepiploic vein is the upper limit when an antrectomy is to be performed. Attention is then directed to the lesser omentum, which is divided from the emergence of the hepatic artery to the right toward the level of the left gastric artery; since it is practically avascular it can be divided with electrocautery.

The transition between the corpus and antrum may be indirectly identified near the caudal branch of the left gastric artery and vein, where the nerve of Latarjet is identified. The vasculature is carefully removed where transection is planned in order to expose the bare area of the small curvature as well as the greater curvature.

Fig. 1. View of the posterior aspect of the stomach with greater omentum attached to the specimen as is performed when surgery is due to cancer. (Notice arterial circulation of the lesser curvature.) |

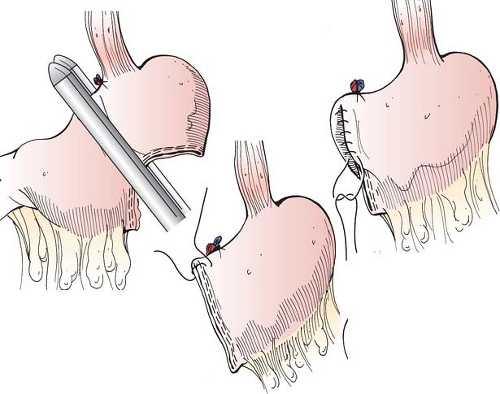

Fig. 2. Transection of the stomach with a linear stapling device and reinforced with Lembert stitches with 3-0 silk. |

Stapler devices can be used to transect the stomach at the desired level although clamps and running suture can also be used in the absence of such technology (Fig. 2). Care should be taken to pull out the nasogastric tube when present to avoid including it in the staple line. After transection of the stomach, the distal part is pulled out of the incision and with the utilization of ultrasonic scalpel or a diathermy device the dissection is continued toward the first portion of the duodenum (Fig. 3). Larger vessels including the right gastroepiploic vessels on the greater curvature, the right gastric artery, and the caudal branch of the left gastric artery on the lesser curvature should be ligated when encountered. The gastroduodenal artery (GDA) should be preserved. The pylorus is then identified and the first portion of the duodenum is skeletonized to the level were the

pancreas adheres; small branches of the GDA may need ligature at this point. Transection of the first portion of the duodenum with a linear stapler device should be performed 2 cm distal to the pylorus. A retracted and fibrous duodenum may add considerable difficulty to this transection. In especially difficult cases where dehiscence and fistulization are likely, a duodenostomy (Foley or Pezzer catheter) can be created through the duodenal stump. Difficult duodenal stumps can also be protected with a side duodenostomy tube at the junction of the second and third portion of the duodenum or a retrograde tube placed at the ligament of Treitz.

pancreas adheres; small branches of the GDA may need ligature at this point. Transection of the first portion of the duodenum with a linear stapler device should be performed 2 cm distal to the pylorus. A retracted and fibrous duodenum may add considerable difficulty to this transection. In especially difficult cases where dehiscence and fistulization are likely, a duodenostomy (Foley or Pezzer catheter) can be created through the duodenal stump. Difficult duodenal stumps can also be protected with a side duodenostomy tube at the junction of the second and third portion of the duodenum or a retrograde tube placed at the ligament of Treitz.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree