Disorders of Sexual Development

Disorders of Genital Differentiation (Disorders Generally Associated with a Normal Chromosome Constitution and Normal Gonad) 18

Disorders of Sex Determination (Disorders Associated with Abnormal Sex Chromosomes and Abnormal Gonadal Formation) 30

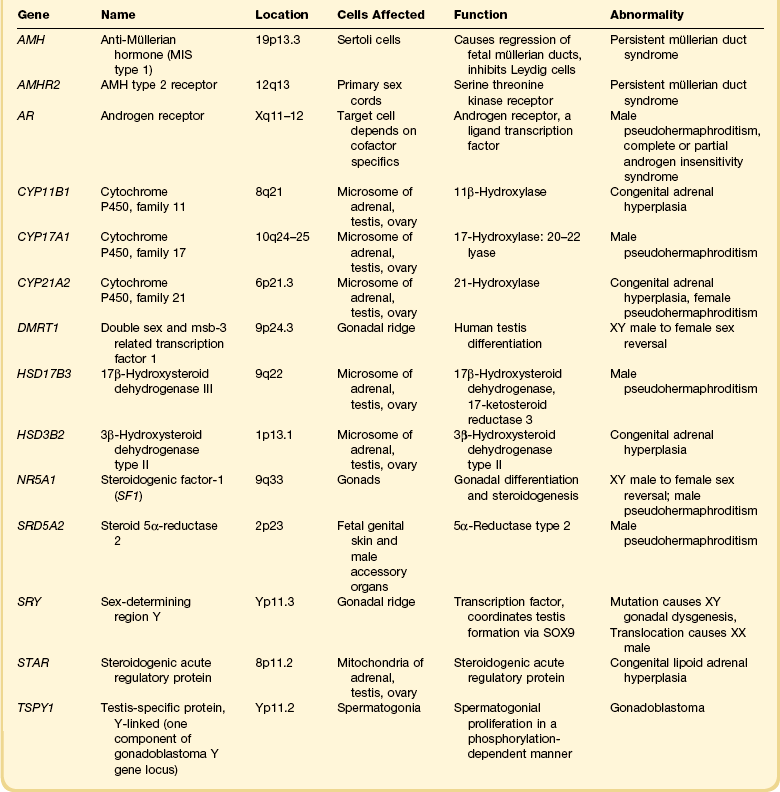

New insights into the biology of sexual development (see Chapter 1) and advances in chromosome analysis are leading to earlier identification and more prompt treatment of the intersexual patient, the results of which facilitate a more normal life for affected individuals.1,2 It becomes easier to offer more appropriate counseling for gender assignment, hormone treatment, and fertility options and information about the risk of future gonadal malignancy. Based on these various advances, a classification of abnormal sexual development has been developed and refined that correlates gonadal and genital anatomy with chromosomal findings and specific genetic or metabolic defects (Tables 2.1 and 2.2). Thus classification has shifted from one primarily based on genotype (whether a specific gene or whole chromosomal abnormality) to broad phenotypic categories of ‘abnormalities of genital differentiation.’ These phenotypic abnormalities may be caused by abnormal production or sensitivity of a single hormone, or abnormal gonadal differentiation, usually testicular, with or without chromosomal aberration.3–5

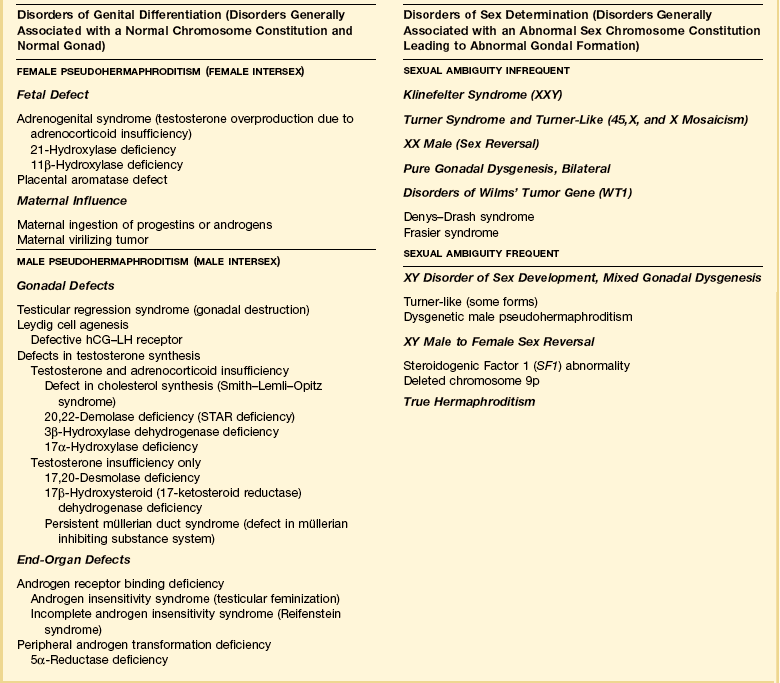

Table 2.1

Classification of Intersexual Disorders*

*Idiopathic or unclassified conditions exist within each major category. We assume that each category of male pseudohermaphroditism with defects in specific protein products or receptors has forms where the abnormality is total or partial, or where the defect results from a qualitatively abnormal structure.

The complexity of the subject is evident from studies in which precise assignment of the etiologic cause cannot be determined in nearly half of the cases by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, biochemists, molecular biologists, and pathologists. The current classification is an integrated approach to this complex group of disorders, organized by clinical presentation and underlying pathophysiology. The classification also groups patients who are at high risk for development of gonadal neoplasia (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3

Gonadal Tumors and Abnormal Sexual Development

| Tumor | Associated Abnormal Sexual Development |

| Leydig cell hyperplasia (pseudotumor) | Adrenogenital syndrome |

| Luteoma of pregnancy | Maternal virilizing tumor |

| Intratubular germ cell neoplasia | Congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia (defect in STAR gene) |

| Sertoli cell hamartomas; Leydig cell nodules; seminoma | Androgen insensitivity syndrome (testicular feminization) |

| Mediastinal germ cell tumors Rarely, Leydig cell tumors Breast cancer; hematologic malignancies | Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) |

| Non-germ cell (serous carcinoma of ovary; endometrial cancer) Stromal luteoma or hilus cell hyperplasia Extragonadal tumor of neurogenic origin | Turner syndrome and Turner-like (X0 and X mosaicism) |

| Wilms’ tumor; gonadoblastoma | Denys–Drash syndrome |

| Gonadoblastoma | Frasier syndrome; 46,XY Disorder of Sex Development |

| Germinoma; rarely, gonadoblastoma | True hermaphroditism |

Disorders of Genital Differentiation (Disorders Generally Associated with a Normal Chromosome Constitution and Normal Gonad)

Female Pseudohermaphroditism (Female Intersex)

Fetal Defects

Adrenogenital Syndrome

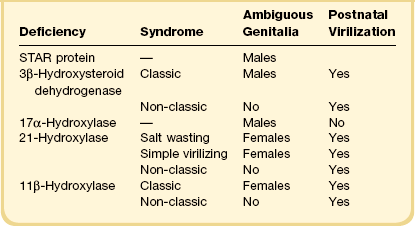

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia, unlike all other conditions responsible for the appearance of ambiguous genitalia in the newborn, may be life threatening because of a lack of synthesis of specific adrenal steroids. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate therapy are essential. With early treatment, normal external genitalia and fertility can be achieved. The manifestations of the adrenogenital syndrome in the 46,XX individual are most easily understood by examining the simplified biosynthetic pathways of mineralocorticoid, glucocorticoid, and sex steroids (Figure 2.1).6–8 Two enzymes, 21 hydroxylase and 11β-hydroxylase, participate in the formation of the glucocorticoids desoxycorticosterone and cortisol and the mineralocorticoid aldosterone, but are unnecessary for synthesis of the sex steroids testosterone, estrone, and estradiol. Deficiency of either enzyme in the 46,XX female leads to elevated adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) products and hence elevated levels of testosterone and other strongly androgenic intermediates, which may result in sexual ambiguity or marked virilization of the newborn’s external genitalia (Table 2.4).9,10

3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase is required for testosterone formation. In its absence, the principal androgen to form is the weak androgen dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), which has 1/20 the potency of testosterone. Patients with deficiency of this enzyme, therefore, show signs of no more than mild virilization, usually with clitoral hypertrophy but not with labial fusion or anterior displacement of the urethral orifice.11

21-Hydroxylase deficiency is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait caused by abnormalities of the CYP21A2 gene on chromosome 6 (which encodes for cytochrome P450, family 21). It accounts for more than 95% of cases of congenital adrenal hyperplasia, occurring once in 15,000 births, and is especially high in Ashkenazi Jews (1 : 27 live births). The clinical manifestation of classic congenital adrenogenital syndrome depends upon inactivation of the normally expressed copy of the CYP21A2 gene. In three-quarters of cases the cause is rearranged inactive elements of a homologous nonexpressed pseudogene, CYP21A1P.6 Deletion of the CYP21A1 gene itself causes the remaining cases. If the allele carries a defect encoding for a mild defect, then the child will develop a non-classic form of adrenal hyperplasia, which by definition occurs after birth and is never associated with genital ambiguity.12 This latter syndrome is common, occurring in 1% of all women, and is the major cause of adult-onset virilism.

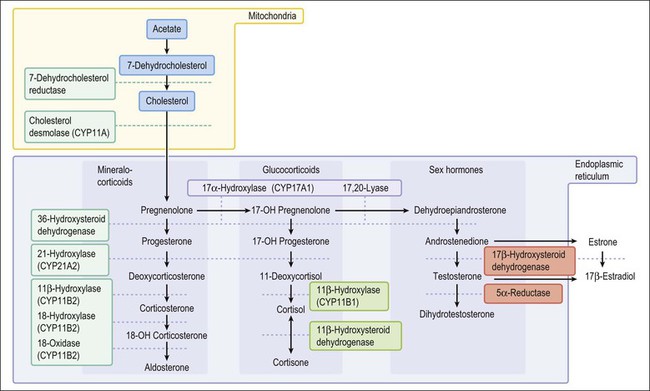

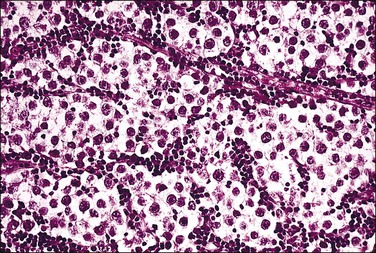

Males who have the adrenogenital syndrome show no evidence of genital ambiguity, but may have an enlarged phallus and a hyperpigmented rugated scrotum. Clinically detectable bilateral testicular nodules occasionally develop during childhood or young adulthood and must be distinguished from true Leydig cell tumors (Figure 2.2).13 Usually the cells are composed of interstitial cells larger than Leydig cells, secrete cortisol, and respond to treatment with the adrenolytic agent o,p′-DDD (mitotane), indicative that these cells are adrenal or adrenal like in origin. Bilaterality and decreasing tumor size after corticosteroid therapy are features indicative that this testicular ‘tumor’ of the adrenogenital syndrome is hyperplastic rather than neoplastic.14

Placental Aromatase Defect

Placental aromatase deficiency is a rare cause of maternal virilization during pregnancy and pseudohermaphroditism of the female fetus.15,16 Mutations in the aromatase gene, CYP19A1, which causes abnormally low conversion of androstenedione to 17β-estradiol and estrone, result in virilization of the mother and her female fetus because potent androgens that are not converted to estrogens accumulate. The mothers usually show the onset of progressive virilization during the third trimester. The male fetus has normal genitalia.

Maternal Influence

Maternal Virilizing Lesions

A variety of benign and malignant tumors and tumor-like conditions, primary as well as metastatic to the ovary, have been associated with virilization of the mother and/or her female offspring.17,18 The luteoma of pregnancy and pronounced theca–lutein cysts (hyperreactio luteinalis) are the most common lesions that cause maternal virilization during pregnancy.19 These are benign hyperplastic lesions of the ovaries encountered most often as an incidental finding at the time of cesarean section or postpartum sterilization, usually in women who are multiparous. Elevated levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) induce hyperplasia of theca–lutein or stroma–lutein cells, which are responsible for the production of androgen (principally androstenedione). Some female infants become masculinized, with mild enlargement of the clitoris and occasionally minimal degrees of labioscrotal fusion or rugate, hyperpigmented (‘scrotal’) labia. The nature of these changes indicates that the ovarian nodules do not function until the second half of gestation, which agrees with the occasional onset of masculinization in the mother during the third trimester.

Male Pseudohermaphroditism (Male Intersex)

Primary Gonadal Defects

Testicular Regression Syndrome

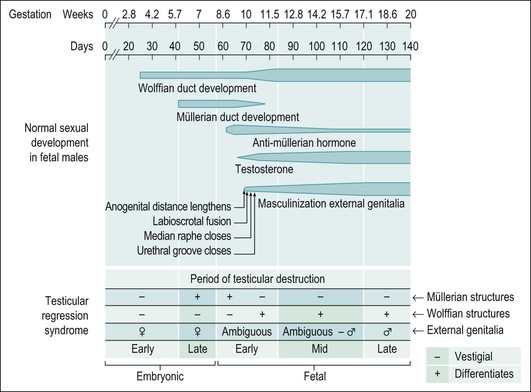

The phenotype of an affected individual with testicular regression syndrome reflects the specific stage of fetal development during which the testes were damaged. In general, gonadal regression that occurs during embryonic life, before the elaboration of AMH and/or androgenic steroids by the testes, leads to a female phenotype. Regression of the testes during late embryonic through mid-fetal life permits a masculine phenotype (Figure 2.3). Testicular regression has a variety of etiologies, as diverse as inherited genetic defect, intrauterine infection, or infarction. The heterogeneous presentations of this syndrome and its relative rarity have led to numerous and sometimes confusing terms for this disorder, including: true agonadism, testicular dysgenesis, rudimentary testis, vanishing testis, and complete bilateral anorchia. Pure gonadal dysgenesis (Swyer syndrome) has been used to designate some forms of the testicular regression syndrome, but this term is nonspecific and thus best avoided.

Figure 2.3 Testicular regression syndrome. The phenotypic appearance of the internal genitalia abnormalities relates to the time during embryogenesis when the normal development of the genital tract was damaged.

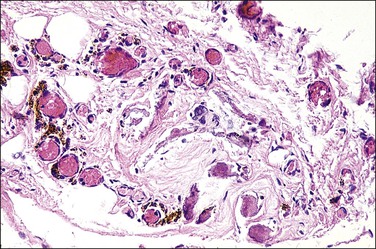

At one end of the testicular regression syndrome spectrum, the internal genitalia and gonads are absent and the external genitalia are female. Presumably, the urogenital ridge was destroyed in its entirety during early embryonic life, even before the müllerian ducts began to differentiate (prior to day 42). At the other end of the spectrum, which approximates the endpoint of normal genital development, the patients are phenotypic males with infantile to nearly normal male external genitalia, normally differentiated wolffian duct structures, and completely inhibited müllerian duct development. Often in these cases, no gonadal tissue is identified. However, there is sometimes a focus of vascularized fibrosis (85%), hemorrhage or hemosiderin deposition (70%), and calcification (60%) or giant cells at the expected site of the gonad, which is near the residual vas deferens or epididymis (Figure 2.4).20 Occasionally, atrophic seminiferous tubules may be found amidst the fibrous stroma. Testicular regression presumably develops during the late fetal period (after 120 days) when müllerian structures have already atrophied under the influence of AMH, and testosterone and dihydrotestosterone have exerted a major influence on the normal development of internal and external genitalia, respectively. Torsion and infarction of improperly descended testes have been suggested.21

Figure 2.4 Testicular regression syndrome. Vascularized fibrosis, hemosiderin deposition, and calcification are seen at the expected site of both gonads.

Leydig Cell Deficiency

Leydig cell deficiency is a rare cause of male pseudohermaphroditism that may have more than one etiology. Some cases may lack Leydig cells altogether, while in others those present are dysfunctional, having an abnormal fibroblast-like morphology.22 Affected individuals have a 46,XY karyotype and testes with interstitial fibrosis, but lack mature Leydig cells and testosterone production. Tubules with Sertoli cells and, sometimes, immature spermatogonia are found. The müllerian structures are absent, indicating appropriate testicular production of AMH by Sertoli cells during fetal life. The wolffian duct system is developed either partially or fully such that identifiable vasa deferentia and epididymides are present. The phenotype varies and is usually female with unremarkable or ambiguous external genitalia, although unambiguous males with evidence of primary hypogonadism have been reported. The presence of wolffian duct development and the variable degrees of masculinized external genitalia indicate that some Leydig cells must have differentiated and functioned during early fetal life. Luteinizing hormone (LH) levels are elevated in affected individuals. Because this condition is so rare, it is uncertain whether the underlying defect is an absence or a defect of the LH–hCG receptor on the Leydig cell or with some other, unknown, factor arresting Leydig cell development.

Defects in Testosterone Synthesis

Congenital deficiency of any enzyme involved in testosterone production in the testis or adrenal gland results in a state of androgen deficiency (relative estrogen excess). The histologic appearance of the testicular tissue is variable. Although described occasionally as ‘normal,’ the photomicrographs in some reports have disclosed large clusters of Leydig cells surrounding tubules lined only by Sertoli cells. Spermatogonia are often normal in children, but disappear by puberty.23 In general, the number of gonads studied for any of the conditions and the ranges of ages studied (infancy, childhood, adulthood) have been limited. Müllerian structures are absent, but wolffian duct structures may be present. The degree to which the external genitalia develop depends upon the type and severity of the defect.

Defect in Cholesterol Synthesis (Smith–Lemli–Opitz Syndrome).

Cholesterol synthesis is required for testosterone and all other hormones that the gonads and adrenal glands produce. The Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome, inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, results from an enzymatic defect in the last step of cholesterol metabolism (reduction of 7-dehydrocholesterol due to mutations in the DHCR7 gene).24 These patients variably show ambiguous genitalia with hypospadias, and more constantly a wide range of other somatic abnormalities including a distinctive facial appearance (microcephaly, ptosis, small upturned nose, micrognathia), cleft palate, and limb anomalies (proximally placed thumbs, polydactyly, and 2–3 toe syndactyly).25 Several 46,XY infants with female external genitalia and intra-abdominal testes with epididymides and deferent ducts had a normally shaped uterus and vagina.26,27 The Y chromosome is normal in these cases, with the affected DHCR7 gene located at 11q13.27

Congenital Lipoid Adrenal Hyperplasia.

Congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia (lipoid CAH), the most severe form of CAH, results from mutations in the steroidogenic acute regulatory (STAR) gene as the primary defect (Table 2.2).28 The STAR gene, located on chromosome 8, encodes a protein that helps transport cholesterol into the mitochondria.29 The principal effect is the absence of cholesterol intermediates capable of converting to pregnenolone. Additional damage occurs from the subsequent steroidogenic loss independent of STAR, and results from the effects of the cholesterol esters that accumulate in the adrenal cortex. This leads to cellular damage in the form of salt wasting, hyponatremia, hypovolemia, hyperkalemia, acidosis, and death in infancy. This state of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism shows markedly elevated levels of gonadotropic hormones (LH, follicle-stimulating hormone, ACTH), but markedly impaired synthesis of all gonadal and adrenal cortical steroids, even with trophic stimulation tests.

In the 46,XY male, the external genitalia may be ambiguous to female, but sufficient testosterone must have been secreted during embryogenesis since the internal genitalia are male. Some of these patients may have a palpable gonad in the inguinal canal. These testes disclose immature seminiferous tubules with spermatogonia. Occasional Leydig cells are present. The germ cells may disappear over time, resulting in a Sertoli-only syndrome, although this is not inevitable. Germ cells can persist and rarely develop into intratubular germ cell neoplasia.30

The deficiency of 3β-hydroxylase dehydrogenase, like the 20,22-desmolase deficiency, results in decreased synthesis of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid hormones as well as adrenal and testicular sex hormones, and may lead to life-threatening salt wasting in infancy. DHEA, a weak androgen secreted in high amounts, results in slight clitoral enlargement in the female, but rarely completely masculinizes the external genitalia in males. Hence, the male may be born with ambiguous genitalia and may resemble a virilized female. Males in whom the defect is partial may be born with hypospadias, but at puberty develop gynecomastia. Over time, the Sertoli cells, which may initially appear normal, undergo atrophy and the spermatogonia change from abundant to rare to absent. The number of Leydig cells may increase with age, but it is unclear whether the hyperplasia is absolute or relative to the atrophy of other elements.31

Deficiency of two enzymes, 17,20-desmolase and 17-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (formerly 17-ketosteroid reductase), results in deficient testosterone synthesis but does not affect the production of either mineralocorticoids or glucocorticoids. The former defect (conversion of 17-hydroxypregnenolone to DHEA) is extremely rare. The patients present with ambiguous external genitalia and inguinal or intra-abdominal testes. Spermatogonia were present in the testes of infants but were absent in the biopsies of their older teenage relatives. All had third-degree hypospadias, but normal male internal ductal differentiation.

Genetic males with 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) deficiency have uniformly been raised as females and have unambiguous female external genitalia. Most are diagnosed at or after puberty when they fail to menstruate and instead show signs of virilization such as clitoromegaly (enlarged phallus) and hirsutism.32 Breast development may or may not take place. At surgery, müllerian duct derivatives are absent, consistent with normal AMH action. Wolffian duct differentiation, indicative of testosterone secretion during embryogenesis, is normal.33 The testes present in the inguinal canal or labia majora contain rare to no spermatogonia, and may exhibit numerous Leydig cells. Detailed endocrine studies have shown that testicular 17β-HSD is under a different genetic control from that in extragonadal tissues, and while affected males lack testicular 17β-HSD, the extragonadal activity is normal or enhanced. More than 15 mutations have been identified in the responsible gene.11,33

Defect in Müllerian Inhibiting System (AMH and its Receptors)

The persistent müllerian duct syndrome, also known as ‘hernia uteri inguinalis,’ is a rare form of male pseudohermaphroditism where müllerian duct structures persist in 46,XY phenotypic males (Figure 2.5). Most patients present when young with unilateral or bilateral cryptorchid testes, normal or almost normal male external genitalia, and an inguinal hernia into which prolapses an infantile uterus and fallopian tubes.34,35 Some patients may be older.36 The testes are histologically normal, wolffian duct structures are developed, the pubertal development is normal, and a rare patient has been fertile. Treatment is surgical, consisting of orchiopexy and herniorrhaphy with hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy.

Persistent müllerian duct syndrome is a heterogeneous group of disorders caused by at least two different defects in the müllerian inhibiting system. The most common is a defect in the anti-müllerian hormone gene, AMH (the protein is also called MIS). The next most common is a defective AMH type II receptor.37,38 The effect of these abnormalities is that some patients produce no biologically functional AMH, whereas others who produce normal amounts of biologically active AMH have end-organ insensitivity or an abnormality of the timing of AMH secretion. On rare occasion, a germ cell tumor may develop in the gonad, and, exceptionally, a müllerian-type tumor develops in the genital tract.39

End-Organ Defects

Androgen Receptor Disorders (Androgen Insensitivity Syndromes)

Disordered androgen receptor function results in various phenotypes, which range from phenotypic women with intra-abdominal testes, to individuals with ambiguous genitalia, and to phenotypic men with minimal clinical abnormalities. One classification scheme40 lists four categories, which are in order of increasing virilization (decreasing feminization):

1. Complete testicular feminization

2. Incomplete testicular feminization

3. Reifenstein phenotype: gynecomastia and hypospadias

About 70% of cases share an X-linked recessive inheritance through the carrier mothers, the result of mutational defects in the androgen receptor gene, which is in the X chromosome’s long arm. In another 30%, the mutation arises de novo.41 Other genetic mutations are known, many of which are limited to individual families.42,43 These mutations may lead to functional absence of the androgen receptor because the primary sequences of the gene are affected. These patients generally present as complete testicular feminization. The more common defect results from single amino acid substitutions and is associated with the various other forms of the disease as described below. In rare patients the androgen receptor disorder occurs in combination with other unusual karyotypes, e.g., 47,XXY and 47,XYY.

Complete Androgen Receptor Insufficiency (Complete Testicular Feminization).

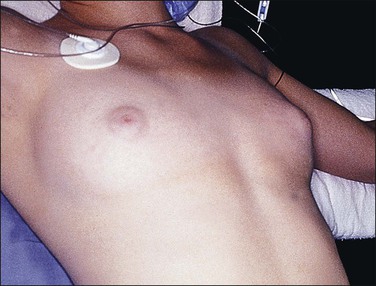

Complete testicular feminization, the most common form of male pseudohermaphroditism, occurs in 1 : 20,000 newborns. The external genitalia are phenotypically female (Figure 2.6) and, for this reason, the condition is rarely diagnosed before puberty unless an inguinal hernia or labial mass is encountered or unless the disease is known to be familial. Primary amenorrhea is the most common complaint leading to evaluation and subsequent diagnosis. The medical history usually reveals that breast development occurred as expected at puberty, but remains in the pubertal state (Figure 2.7). Pubic and axillary hair is scant (Figure 2.8) and the vagina is shortened. The epididymides are usually cystic and not connected to the testes. The vasa differentia, seminal vesicles, and prostate are absent. As a rule, both the cervix and the uterine corpus are absent. Fallopian tube fragments are found in one-third of cases.44 The testes are cryptorchid and may be located in the inguinal canal, the pelvis, or rarely the labia.

Figure 2.7 Immature breast development and lack of axillary hair in androgen insensitivity syndrome.

In the complete or almost complete form of the syndrome, the individual exhibits a female gender identity with normal extragenital erotogenic sensitivity and normal maternal attitude, emphasizing the need to support the patient as a woman, even with reconstructive surgery.45 This condition should be differentiated from defects in steroidogenic factor-1 mutations (XY, sex reversal with androgen insensitivity-like features) with which it can be confused.

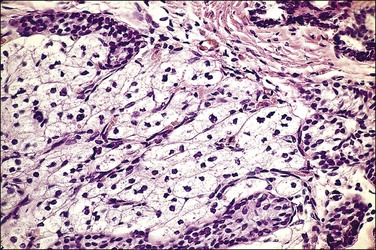

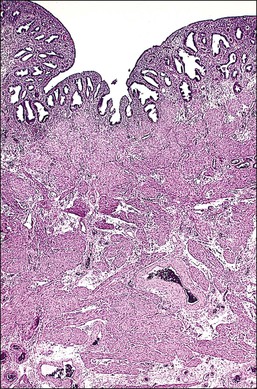

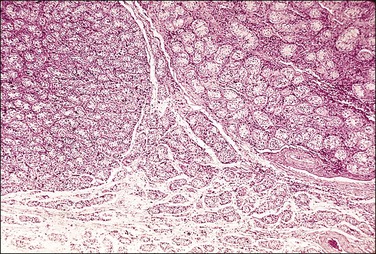

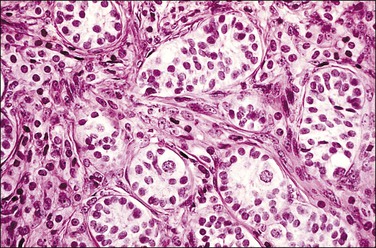

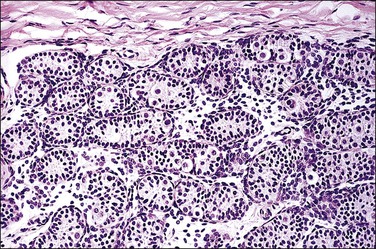

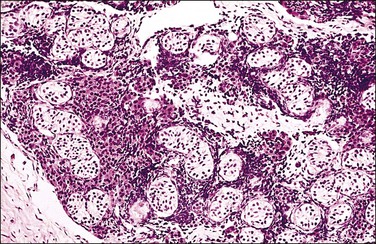

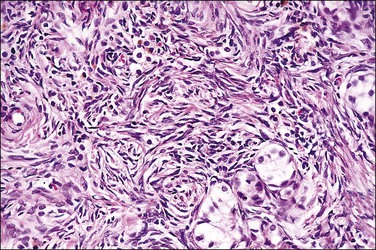

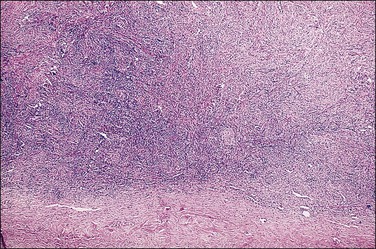

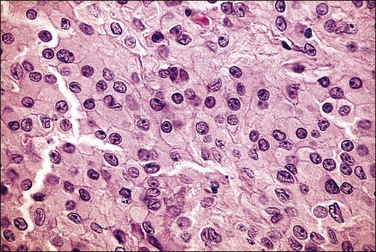

The gonads in infants and young children are relatively normal but, by age 5 years, they show abnormalities. By young adulthood, the gonad is often involved with benign or malignant tumors as described later. If tumors are not present by this age, the gonad is usually small and on section is tan to brown and traversed by thin white bands (Figure 2.9). Microscopic examination of the testicular parenchyma discloses immature seminiferous tubules. At earlier ages, the tubules may be clustered in small aggregates (Figure 2.10), but with time they become more sparsely distributed (Figure 2.11). Spermatogonia may be present, but spermatogenesis is absent. The number of spermatogonia found is also age dependent, diminishing as the patient ages. The interstitium, which resembles ovarian stroma, is usually abundant at an early age and over time often becomes more fibrous (Figure 2.12). Fetal-type Leydig cells may be abundant. The Leydig cells in individuals with testicular feminization have an ultrastructure typical of cells involved in active hormone synthesis and the systemic androgen levels in these individuals are typically elevated. These findings indicate that the pathologic defect in the testicular feminization syndrome is an end-organ defect and not lack of hormone production by the testes.

Figure 2.10 Androgen insensitivity syndrome. Immature seminiferous tubules, numerous Leydig cells, and rare foci of immature ovarian-type stroma constitute the testis.

Figure 2.11 Androgen insensitivity syndrome. Scattered immature seminiferous tubules are embedded in the dense ovarian-type cortical stroma present in the testis.

Figure 2.12 Androgen insensitivity syndrome, gonad in an older patient. Dense ovarian-type cortical stroma with extremely rare scattered immature seminiferous tubules constitute the testis.

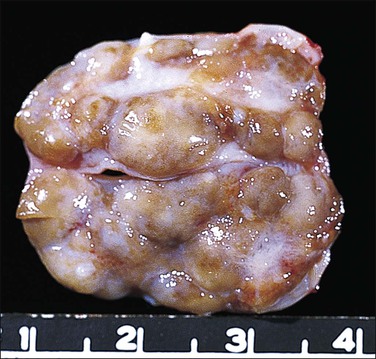

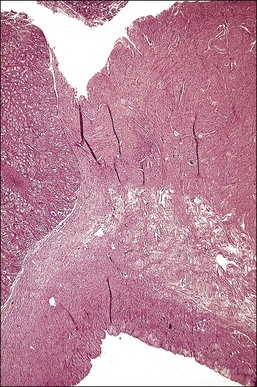

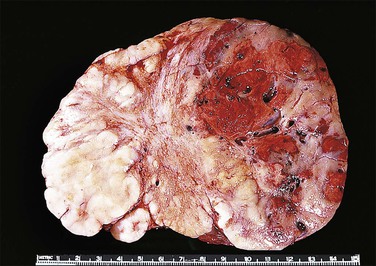

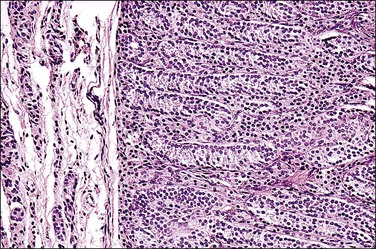

Most testes of affected individuals contain multiple benign nodules that are discrete, firm, yellow to brown, and bulge above the sectioned surface (Figure 2.13). These can be hamartomatous (e.g., Sertoli cell adenoma) or neoplastic (e.g., dysgerminoma or gonadoblastoma like). One finding we have seen characteristically is a 1–2 cm firm white nodule of hyalinized smooth muscle leiomyoma-like tissue that is usually present at one pole of the testis (Figure 2.14). Reactivity for smooth muscle actin confirms its smooth muscle origin (Figure 2.15). Additionally, hamartomatous nodules are present, usually bilaterally, in virtually every case. The typical size varies from 1 mm to 1 cm, but occasionally up to 4 cm.44 The bulk of the nodule consists of seminiferous tubules lacking lumina (Figure 2.16). Spermatogonia may be present (Figure 2.17). The seminiferous tubules located outside the nodules have a lamina propria that is of normal thickness in prepubertal testes, but thickened and hyalinized in the adult.46 Sertoli cell adenomas, which average 3 cm in diameter, but range to 25 cm (Figure 2.18), are hamartomas composed predominantly or exclusively of closely packed immature seminiferous tubules lacking lumina and lined by immature, uniform Sertoli cells (Figure 2.19), some with germ cells (Figure 2.20).44,47 The interstitium in the testes of affected patients often resembles ovarian stroma, and frequently contains Leydig cells (Figure 2.10). On rare occasion, Leydig cell nodules form, and have been considered benign tumors (Figure 2.21). Even though tumors have been reported occasionally as malignant, none has shown evidence of invasion or dissemination grossly or microscopically.48 In summary, the name applied to each type of nodule is somewhat arbitrary and depends largely upon the types of component present as well as their number and size. Most nodules are classified as hamartomas, Sertoli cell adenomas, or rarely as Leydig cell tumors.

Figure 2.13 Androgen insensitivity syndrome. Several small yellowish Sertoli cell adenomas are present throughout the specimen. The large white mass at the inferior pole may represent a hypertrophied gubernaculum testis or a leiomyoma present since birth.

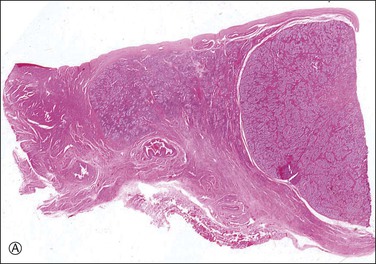

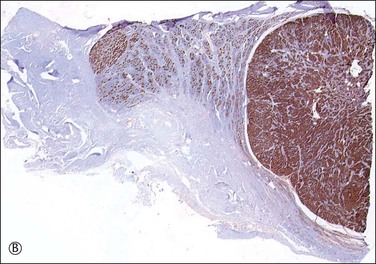

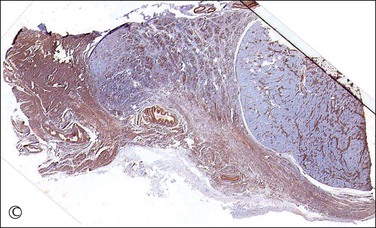

Figure 2.15 (A) Androgen insensitivity syndrome with Sertoli adenoma (right) and hypertrophied gubernaculum (left). The adenoma expresses AMH (B), and smooth muscle actin is positive in the gubernaculum (C).

Figure 2.19 Interface of Sertoli cell adenoma (right) and adjacent degenerative seminiferous tubules (left) in androgen insensitivity syndrome.

Figure 2.21 Leydig cell tumor in androgen insensitivity syndrome. Detail of a well-circumscribed gross nodule showing sheets of cells with large central nucleus and copious cytoplasm.

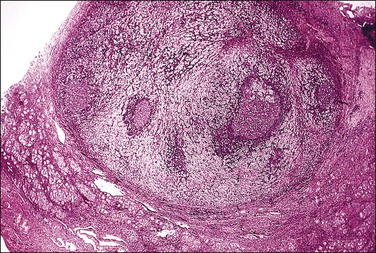

Malignant gonadal tumors develop with increasing frequency with age in patients with testicular feminization. Seminoma is the most commonly encountered gonadal malignancy in this syndrome. Intratubular germ cell neoplasia is sometimes seen, either independently or in association with seminoma (Figures 2.22 and 2.23). Other malignant germ cell tumors and malignant sex cord tumors are also encountered rarely. Unlike mixed gonadal dysgenesis in which tumors develop in young individuals, the risk of malignancy in patients with testicular feminization is only 4% by the age of 25 years, but reaches 33% by 50 years.49 Since malignant tumors rarely develop before completion of puberty, castration can usually be delayed until after adolescence, thus permitting the patient to undergo normal pubertal development with spontaneous female secondary sex characteristics.

Partial Androgen Receptor Insufficiency (Incomplete Testicular Feminization).

About 10–50% of patients with the androgen insensitivity syndrome have an incomplete variant.50,51 The clinical manifestations vary depending on the classification system used. If restricted, it resembles complete testicular feminization except that there is partial fusion of the labioscrotal folds and usually some clitoromegaly at birth. If inclusive of all forms of the androgen insensitivity syndrome that are not considered complete testicular feminization, then greater percentages of patients will look and be raised as males.50,51 Viewed broadly, patients with partial androgen receptor insufficiency form one of the largest groups of intersex patients born with male sex ambiguity.4 Like the complete form, underdeveloped wolffian duct derivatives are often present. If the diagnosis is established during childhood, gonadectomy should be performed before puberty, since disfiguring virilization may accompany breast development at puberty. Estrogen therapy should be given at the appropriate time to initiate feminization. The pathologic findings are those described for the complete form of testicular feminization.46

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree