Chapter 11 Diseases of the oral mucosa

Introduction

From a histological perspective, the oral mucosa is divided into nonkeratinized and keratinized sites. The former include the labial mucosa (wet surface of the lip), buccal mucosa, maxillary and mandibular sulci (sometimes also called the ‘vestibule’), ventral tongue, floor of mouth, soft palate, nonattached gingiva and crevicular epithelium (Fig. 11.1). The crevicular epithelium is the continuation of marginal gingiva where it turns to face the tooth. Any keratin on these surfaces is considered abnormal and should be reported as such. The linea alba (‘bite line’) which is located on the buccal mucosa where the upper and lower teeth meet may be thinly parakeratinized and this is considered within the realm of normal (Fig. 11.2).

Keratinized sites include the hard palate mucosa, the attached gingiva (extending from the tooth for a band of 3–7 mm) and the tongue dorsum. The tongue is a specialized structure because of its role in taste sensation and has filiform, fungiform, and circumvallate papillae, the last two also containing taste buds (Fig. 11.3).

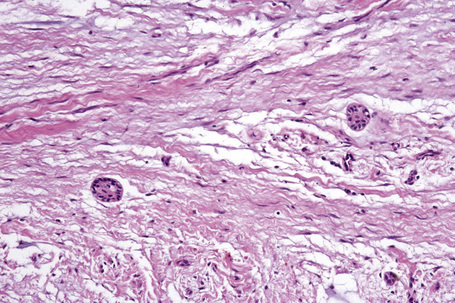

The oral mucosa consists of epithelium and underlying lamina propria that can be arbitrarily divided into superficial and deep portions, and underlying muscle or bone. Since there is no muscularis mucosa, there is no true submucosa. The epithelium of the oral mucosa is thickest on the tongue dorsum and thinnest on the floor of mouth and is generally two to four times thicker than the epidermis (Fig. 11.4). Pathologists not familiar with this feature tend to diagnose normal mucosa as acanthosis or psoriasiform hyperplasia. The attached gingiva and mucosa of the hard palate abut the periosteum so that the deep lamina propria appears densely fibrotic (Fig. 11.5). A diagnosis of ‘fibrosis’ is therefore inappropriate since this feature is normal for the site.

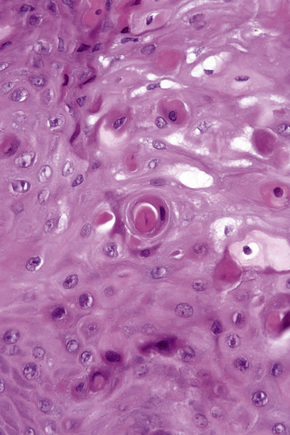

The tooth is composed of an outer highly calcified thin shell of enamel on the visible crown of the tooth; the non-visible portion within the bone is covered by cementum, which is similar in composition and appearance to bone. The bulk of the tooth consists of dentin and through the tooth runs the pulp containing fibrovascular and neural tissues (the source of most toothaches). Odontogenic epithelium is often seen within the gingival tissues and in odontogenic tumors in the gingiva. This consists of nests of squamous epithelium that may have clear cytoplasm and sometimes show palisading of the basal cell nuclei (Fig. 11.6).

Hereditary conditions

Macular lesions

White sponge nevus

Clinical features

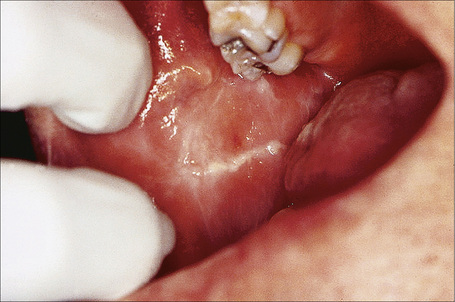

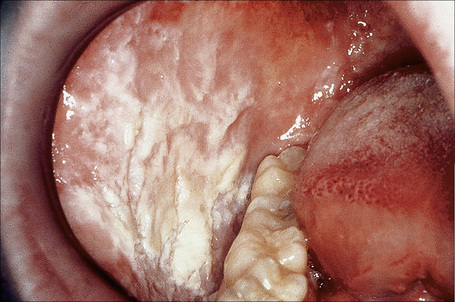

White sponge nevus (Canon white sponge nevus, leukoedema exfoliativum mucosae oris, familial white folded dysplasia of mouth) is an autosomal dominant condition with high penetrance and variable expressivity. Onset is in early childhood with 50% of patients diagnosed before age 20.1–3 The buccal mucosa is almost invariably affected and other common sites are the labial mucosa, tongue, alveolar mucosa, and the floor of mouth. Nasal, esophageal, vaginal, anal, and penile mucosae may be involved, but not that of the conjunctiva, although there is one report of associated colobomas.4 Lesions appear as diffuse, white-to-gray, painless, spongy, folded plaques with a tendency to slough off (Fig. 11.7).2,5,6 There may be periods of exacerbation and remission.

Pathogenesis and histological features

White sponge nevus has been traced to a mutation in the helical domain of mucosal-specific keratins K4 (on chromosome 12q) and K13 (on chromosome 17q). The mutations are in the form of amino acid deletions, substitutions, and insertions resulting in keratin filament instability and abnormal aggregation of tonofilaments.7–9 Since some cases remit with antibiotic therapy, this suggests that infections and/or inflammation may play a role in the expression of disease.10,11

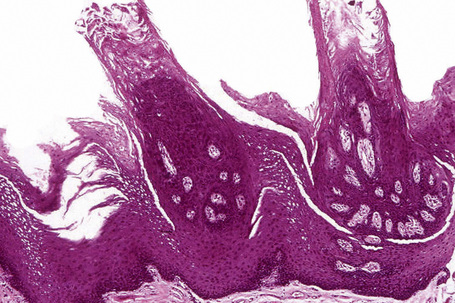

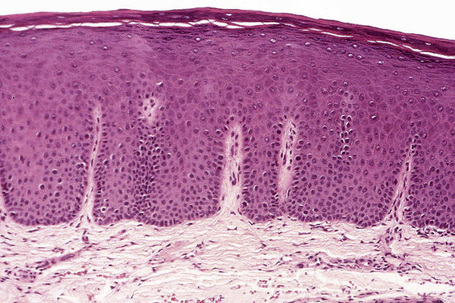

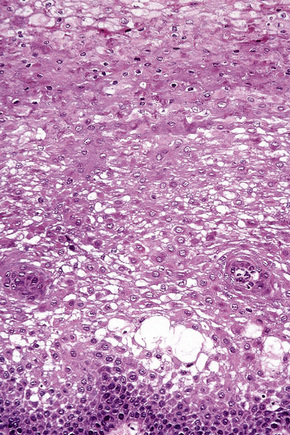

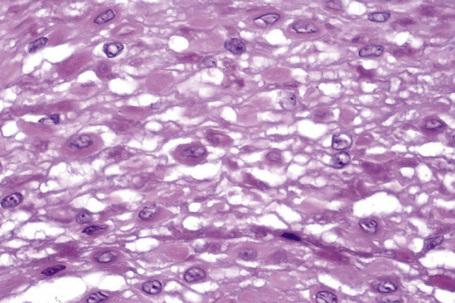

There is parakeratosis, acanthosis with the formation of large, blunt rete ridges, vacuolation of cells; anucleate keratinocytes are present superficially (Fig. 11.8). Dyskeratotic cells exhibit dense peri- and paranuclear eosinophilic condensations and there is insignificant inflammation (Fig. 11.9).5,12,13 Parakeratin plugs and streaks have been noted beneath the superficial keratinocytes. One case that exhibited foci of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis has been documented.14

The eosinophilic condensations correspond to tonofilament aggregates in a peri- and paranuclear location.1,12,13,15 Organelles tend to segregate and are absent in vacuolated cells. Odland bodies are abundant within keratinocytes but few are present in the intercellular spaces, suggesting a lack of acid phosphatase leading to retention, rather than normal shedding, of superficial cells.1

Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis

Clinical features

This autosomal dominant disorder of the eye and oral cavity was first described in a tri-racial isolate (Caucasian, Native American, and African) in North Carolina called the Halowar, Haliwa, or Haliwa-Saponi Indians.1 Because of migration, cases have been reported in descendants living now in New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Washington DC.

The eye lesions, which usually present by the first year of life, are foamy, gelatinous plaques in the bulbar conjunctiva in a perilimbic distribution both nasally and temporally. Patients experience irritation and photophobia and there may be exacerbations in spring. Corneal vascularization sometimes leads to visual loss.2

Oral involvement is asymptomatic and is therefore generally not noticed until the second decade. Lesions involve the buccal and labial mucosa, floor of mouth, lateral and ventral tongue, and gingiva but not usually the dorsum of tongue or uvula.3–5 The mucosa is white, opalescent, spongy, macerated, folded, and shaggy, often resembling white sponge nevus (Fig. 11.10). There is generally no involvement of genital, nasal or rectal mucosa.

Pathogenesis and histological features

Genetic studies have localized the gene for this condition to chromosome 4q35 with a duplication segregating in affected individuals.6

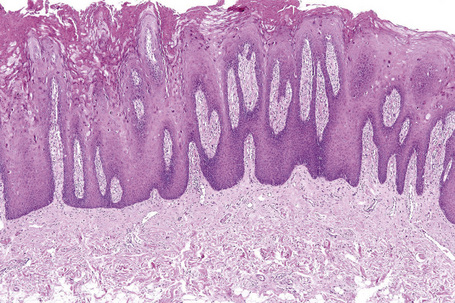

There is hyperkeratosis and acanthosis (Fig. 11.11). Dyskeratotic cells (also called ‘tobacco cells’ because of their orange-brown color on Papanicolaou-stained smears) are present in the mid to upper one-third of the epithelium, appearing engulfed by adjacent normal keratinocytes; this ‘cell-within-a-cell’ appearance is a characteristic feature and is well seen in cytological smears (Fig. 11.12)4,7,8

The dyskeratotic cells are packed with tonofilaments and vesicular bodies that may represent Odland bodies.7 Some keratinocytes also show disappearance of cellular interdigitations and desmosomes.

Pachyonychia congenita

Clinical features

This rare genodermatosis is characterized by nail dystrophy, disorders of the palmoplantar skin and hair and leukoplakia; the larynx and eye may also be affected.1 The oral findings, usually noted within the first two decades of life, are characterized by focal or generalized white hyperkeratotic plaques on the dorsum and lateral borders of the tongue and buccal mucosa, and are present in 75–95% of cases.1–4 Natal teeth (teeth present at birth) are a common finding in the type 2 form of the disease.1,5,6

Pathogenesis and histological features

Histologically, there is hyperparakeratosis or hyperorthokeratosis, acanthosis, and intracellular vacuolization.3,6,8 Because pachyonychia congenita and dyskeratosis congenita are generally diagnosed on skin biopsy, there are few detailed reports on the histology of oral lesions.

Dyskeratosis congenita

Clinical features

Dyskeratosis congenita is another genodermatosis that is associated with nail dystrophy, poikiloderma, oral leukoplakia, and development of pancytopenia, often requiring hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The mucosa of the conjunctiva, urethra, and genital tract may also be involved.1,2 Oral leukoplakia, particularly of the tongue, presents in the second decade of life and has a high propensity for developing dysplasia and/or squamous cell carcinoma at an early age.3,4

Darier’s disease

Clinical features

Oral findings occur in approximately 50% of patients with Darier’s disease (Darier-White disease, keratosis follicularis). Mild involvement comprises minute white or pink keratotic papules, while in more extensive disease coalescence results in larger plaques or a cobblestone surface. Lesions are generally asymptomatic.1–4 The palate is the most common site affected, perhaps because of its normally keratinized nature, followed by the gingiva, tongue, buccal mucosa, and floor of mouth. The lips are rarely involved.5 Recurrent parotid or submandibular swelling may be reported in up to approximately one-third of cases and is most likely the result of strictures in the main duct causing obstruction.4,5 In general, the degree of oral involvement parallels the extent of skin lesions.2,5

Pathogenesis and histological features

This disease is associated with a mutation on the ATP2A2 gene on chromosome 12q that is involved in cytoplasmic calcium transport which is required for proper functioning of desmosomes and keratin formation.6

The typical findings are hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and suprabasal clefting with acantholysis forming vertical villous-like projections protruding into lacunae. Corps ronds and grains may not be as prominent as in skin lesions.2,5 Papanicolaou-stained smears show an orange-brown staining of the dyskeratotic ‘grains’ and refractile concentric perinuclear rings and granular bands in corps ronds.7 The excretory salivary ducts may become metaplastic or involved by the same process leading to stricture formation and obstruction.1,8,9

Warty dyskeratoma

Clinical features

This usually solitary lesion resembles Darier’s disease and may present as a papule or nodule (oral focal acantholytic dyskeratosis) in the oral cavity. It generally occurs in the fifth or sixth decade and almost always arises on the keratinized and attached mucosa of the palate or gingiva with a 2:1 female predominance.1 Most lesions measure less than 1 cm and rare cases develop on the buccal mucosa and tongue.2–4 Interestingly, the majority of cases occur on the left side of the mouth, raising the possibility that trauma plays an important role since most individuals are right-handed and may brush the left side of the mouth more vigorously. The papular variety appears as a white papule or plaque while the nodular variety has an umbilicated or crateriform appearance. There is an association with tobacco use.3,5

Histological features

Oral warty dyskeratoma is characterized by Darier’s disease-like features including suprabasilar clefting with lacunae formation, villous-like projections, corps ronds and grains.3 The papular lesions show multifocal involvement and sometimes papillary epithelial hyperplasia.6 There is no association with underlying sebaceous or salivary glands.

Tumor-like lesions

Choristomas

Osseous choristoma

Clinical features

The majority of these lesions (93%) occur as sessile or pedunculated masses on the posterior dorsum of the tongue, near the foramen cecum, although other sites may be involved.1–4 Most develop in the second and third decades and females are three to five times more likely to be affected.2,4 There may be dysphagia.

Cartilaginous choristoma

Clinical features

Cartilaginous choristomas present as discrete nodules, usually along the lateral border of the tongue (85% of cases) and less often on the buccal mucosa and soft palate.1–3 Most occur in adults.4

Pathogenesis and histological features

Cartilaginous choristoma consists of a mass of benign mature hyaline cartilage surrounded by dense perichondrium; loose myxoid tissue akin to primitive mesenchyme or even mature fat may also be present.2,4,5 Some cases show ossification and association with salivary glands.2,3 Rare cases of chondrosarcoma have been reported.6

Differential diagnosis

Metaplastic cartilaginous nodules are often seen in cases of denture-associated fibrous hyperplasia but these occur in the maxillary and mandibular vestibules associated with denture flanges. Cartilaginous rests are also common in the area of the nasopalatine canal. Some authors believe that cartilaginous rests of the soft palate/tonsillar area are a metaplastic phenomenon, occurring in 20% of tonsils examined.7 A pleomorphic adenoma with extensive chondroid metaplasia should also be considered.

Sebaceous choristoma, hyperplasia and adenoma

Clinical features

Sebaceous glands occur as 1–3-mm yellow macules or papules in the buccal and labial mucosa in approximately 80% of the adult population (Fig. 11.15).1 However, these may become hyperplastic or adenomatous, forming painless papules, plaques or nodules, and are termed sebaceous hyperplasia or adenoma, respectively.2,3 They occur in the same sites as Fordyce granules.

Rare cases of sebaceous choristomas have been reported in the tongue of adults. They present as dome-shaped masses in the midline of the dorsum in the area of the middle or posterior one-third of the tongue, often associated with a thyroglossal duct.4,5

Histological features

Fordyce granules consist of mature lobules of sebaceous glands that communicate with the surface epithelium via a duct. There may be pseudocyst formation with retention of secretions and adenomatous hyperplasia; the rare occurrence of hair follicle and Demodex within a Fordyce granule has been reported.6–8

In sebaceous hyperplasia, at least 15 lobules of mature sebaceous glands empty into ducts that communicate with the surface (Fig. 11.16).2 In the sebaceous choristoma, mature sebaceous units may be associated with eccrine glands, hair follicles, and apocrine glands.5 Sebaceous adenomas also show a proliferation of basaloid cells at the periphery of the lobules.9,10 Some of these may represent sebaceous adenoma of the minor salivary gland.11

Gastrointestinal choristoma

Clinical features

Almost all of these are cystic lesions that present as swellings of the tongue, usually on the ventral surface, or the floor of mouth.1–3 Sometimes they appear as sinuses.4 They are most often seen in infancy or early childhood and may be associated with orofacial malformations.3

Many theories of pathogenesis have been postulated including epithelial entrapment, incomplete coalescence of lacunae, and persistence of intestinal epithelial buds.4,5

The cystic lesions are lined by epithelium typical for the cardiac, fundic or pyloric regions of the stomach with parietal and Paneth cells.4 However, some are lined by colonic and/or ciliated epithelium.5 Smooth muscle is usually identified. The presence of pancreatic tissue has also been reported.6 If ectodermal and mesodermal elements are also present, the lesion should be considered a teratoma.

Pathogenesis and histological features

Heterotopic brain tissue

Clinical features

This uncommon condition presents in the first year of life, most often affecting the palate, tongue (especially the foramen cecum area) or oropharynx, as a result of displacement of primitive neural elements in an early stage of development or neuroglial differentiation from pluripotent cells.1,2 Some patients have associated palatal defects.3 Respiratory obstruction is a major cause of morbidity and feeding difficulties if lesions are large.4

Epidermoid and dermoid cysts

Clinical features

The floor of the mouth is the most common site of presentation and there may be a slight female predilection; some cases are congenital.1–3 Classification of these lesions is based on anatomical location such as lingual, submental or submandibular and on the histological appearance.1,2,4

They present as dome-shaped, yellow masses with a rubbery or doughy consistency. Intraoral lesions cause feeding, swallowing, and speech difficulties while extraoral variants below the myohoid muscle lead to a noticeable submental mass. Dumbbell-shaped cysts have both intra- and extraoral swellings.5

Pathogenesis and histological features

The pathogenesis is uncertain. One theory suggests that they arise from entrapped epithelial rests in the line of fusion of facial processes. Another proposes that the lining develops from displaced embryonic rests or traumatic implantation, possibly occurring even in utero.3

Both epidermoid and dermoid cysts are lined by orthokeratinized squamous epithelium and the lumen is filled with keratinaceous material. Epidermoid cysts (also called epithelial inclusion cysts) have no adnexa in the wall, while dermoid cysts always have skin adnexal structures in the wall. Oral dermoid cysts are three times more common than epidermoid cysts.2

Some cysts also contain gastrointestinal mucosa.6,7 If tissues from all three germ layers are represented, the term ‘teratoid cyst’ may be more appropriate.

Differential diagnosis

Gingival cyst of the adult is generally nonkeratinized and is lined by low cuboidal to columnar or stratified squamous epithelium, with occasional epithelial plaques and clear cells.8 Gingival cysts of the newborn, which are generally not biopsied because they exteriorize on their own, are filled with keratinaceous material.9 Both can be differentiated from epidermoid cysts by their location on the gingiva.

Dermoid tumor (dermoid), teratoma, and epignathus

Clinical features

Of these, the dermoid is the most common.1

Dermoids tend to occur in females (six to seven times more often than in males) as pedunculated masses in the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and soft palate.2,3 The mass is covered by skin, hence its other name, ‘hairy polyp’. It may also grossly resemble an accessory auricle.4

Teratomas, teratoid tumors, and epignathi present as masses that may protrude from the mouth, and airway obstruction is a frequent presenting symptom; there is a female predilection and most are present at birth.5 Unlike dermoids, these tumors are often associated with other malformations and findings such as elevated alpha fetoprotein and polyhydramnios.6,7

Epignathi in particular may be associated with severe congenital malformations, and stillbirth is a common occurrence. They most often arise from the hard palate (hence its name), although the posterior nasopharynx and upper lip can be involved, and there may be palatal clefts and cranial extension.7–9 Grossly, the tumor sometimes contains rudimentary limbs, or even a head resembling an incomplete twin or fetus in fetu.10

Lingual (tongue) teratomas are generally not associated with such developmental defects.11

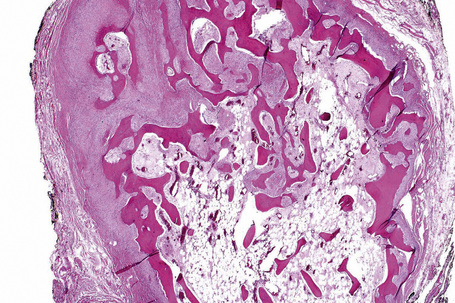

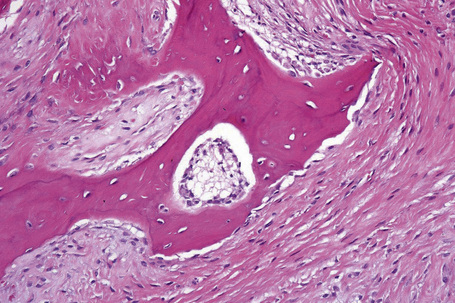

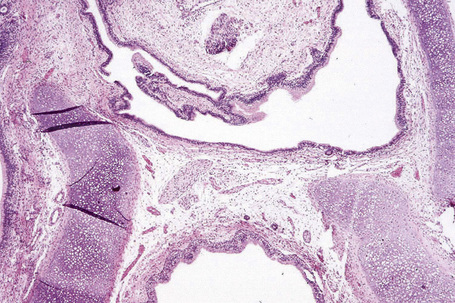

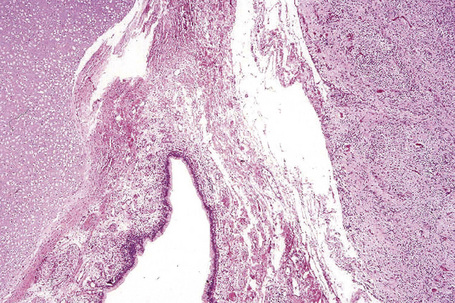

Histological features

Dermoids are covered by skin with its constituent adnexa. In addition, cartilage, bone, muscle, adipose tissue, and even salivary glands may be present (Fig. 11.18).3,7,12 Teratomas contain all of the above. In addition, neural, brain, lung, gastrointestinal, and respiratory tissues are sometimes present (Fig. 11.19).6,11

Fig. 11.18 Dermoid tumor: note the presence of cartilage and columnar epithelium.

By courtesy of the Registry of Oral Pathology, AFIP, Washington DC, USA.

Fig. 11.19 Teratoma: in addition to endodermal elements, glial tissue is present.

By courtesy of the Registry of Oral Pathology, AFIP, Washington DC, USA.

Epignathi consist of tissues organized to form grossly recognizable specific organ systems such as limbs, a head or eyes.7,10

Oral lymphoepithelial cyst

Clinical features

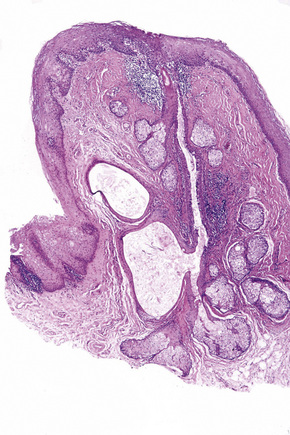

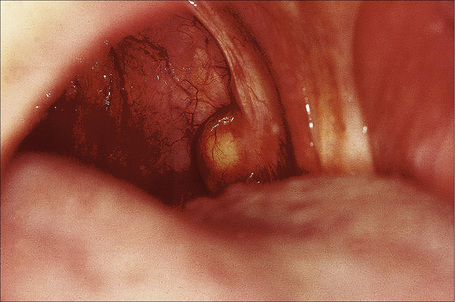

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts generally occur in the fourth decade of life with an equal sex distribution.1,2 These also occur in the parotid gland in particular in HIV-positive individuals.3 They present as painless yellowish nodules, usually less than 1 cm in diameter, most commonly affecting the floor of mouth followed by the posterior ventral tongue, soft palate, and tonsillar fauces (Fig. 11.20).3–5 They are commonly filled with cheesy, keratinaceous material. Some authors consider lesions which present at sites where tonsillar tissue is normally found to be inflammatory/obstructive tonsillar reactions.4

Pathogenesis and histological features

Three theories of pathogenesis have been proposed:

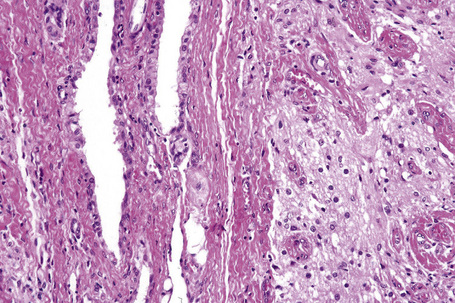

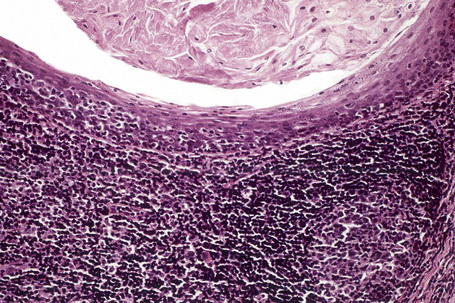

The cyst is lined by parakeratotic stratified squamous epithelium and the lumen is filled with desquamated keratinaceous material (Fig. 11.21).3,4,7 Rare cases may be lined by pseudostratified columnar epithelium with or without mucous cells.5 The epithelium usually demonstrates lymphocytic exocytosis (Fig. 11.22). The surrounding lymphoid tissue may encircle the cyst epithelium completely or partially, and germinal centers are usually well formed although not always present. Some cases demonstrate communication with the overlying surface epithelium, often through a narrow opening.

Salivary glands and ducts may be present in the vicinity, especially floor of mouth lesions.1,3

Lingual thyroid

Clinical features

Approximately 10% of cadaveric tongues contain nests of thyroid tissue, with no sex predilection.1,2 However, when thyroid tissue occurs as a mass in the tongue, the term ‘lingual thyroid choristoma’ or ‘ectopic lingual thyroid’ is used. Since approximately 86% of such tumors consist of the only thyroid tissue in the body, the terms ‘lingual thyroid ’or ‘ectopic lingual thyroid’ are more accurate.3

The lesion presents as a rounded, soft-to-firm mass within the base of the tongue between the foramen cecum and the epiglottis. It may cause dysphagia, dyspnea, dysphonia or hemorrhage.2–4 Females are three to seven times more likely to be affected than males and there are two peaks of presentation, i.e., the first and second decades and the fifth and sixth decades, probably related to hormonal influences;4,5 it is uncommon in children.6 One-quarter of patients may be hypothyroid.

Pathogenesis and histological features

In most cases, a biopsy is not indicated if technetium scans are positive for thyroid tissue. Thyroid follicles may contain mature or embryonic thyroid epithelium and exhibit microfollicular, macrofollicular or adenomatous changes.1,5 There may be an associated thyroglossal duct.2 Follicular and papillary carcinomas can sometimes occur, in the same frequency as one would expect in the normal thyroid gland.7,8; even medullary carcinoma has been reported.9

Congenital granular cell tumor/epulis

Clinical features

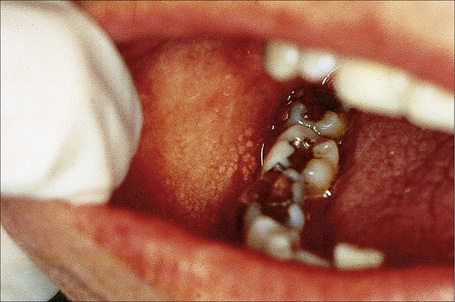

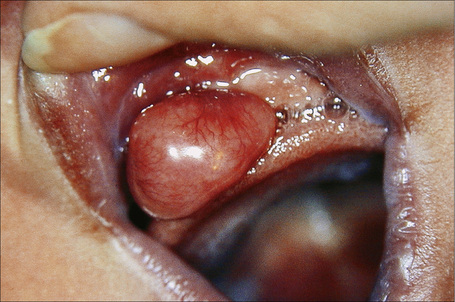

The congenital granular cell tumor presents as a pink, pedunculated mass, usually on the anterior alveolar ridge with an intact surface (Fig. 11.23). There is a 10:1 female predilection and it is three times more common in the maxilla.1 It may cause problems with nursing. Approximately 9% of patients have multiple nodules and some may have concurrent tongue lesions.2–4

Pathogenesis and histological features

Theories of histogenesis have included epithelial, pericytic, and neural derivation. The current hypothesis is that it represents a mesenchymal tumor (some believe of myofibroblastic origin) with evidence of degenerative change. The latter is supported by lack of growth after birth of the infant, resolution of some cases over time, histological evidence of degeneration, and lack of recurrence in spite of incomplete removal.1,5,6

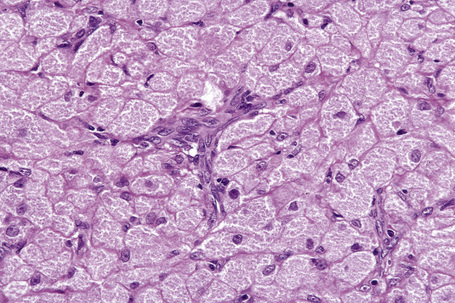

Histologically, a Grenz zone may or may not be present and the overlying epithelium is typically atrophic. The cells are round or polygonal with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, distinct cell borders, eccentric small nuclei, and inconspicuous nucleoli; a prominent delicate and arborizing capillary network is usually evident (Fig 11.24).3,6 The granules are period acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase resistant; odontogenic rests may also be present.4,7

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree