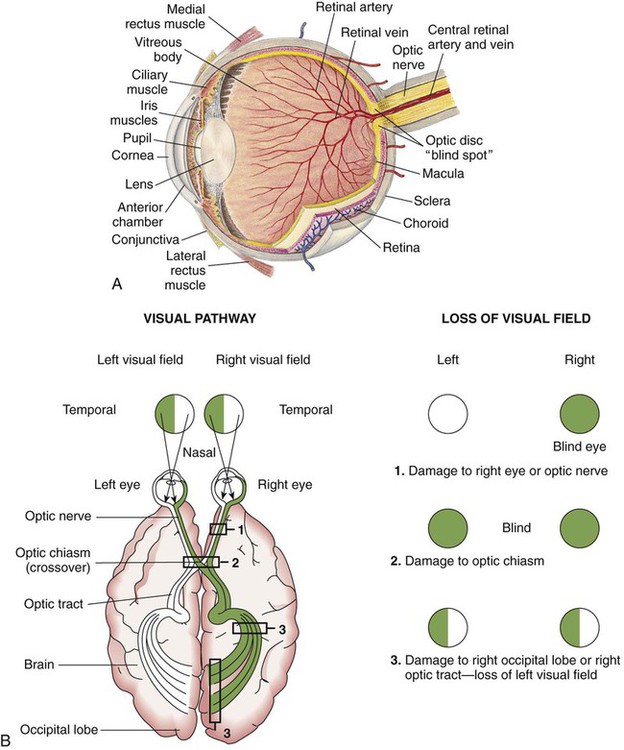

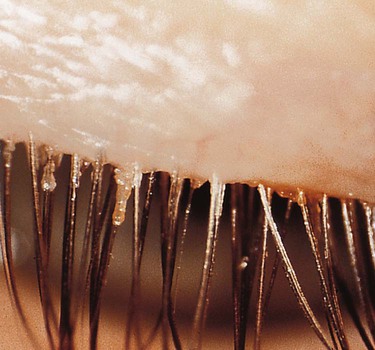

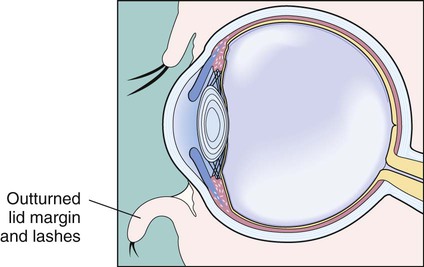

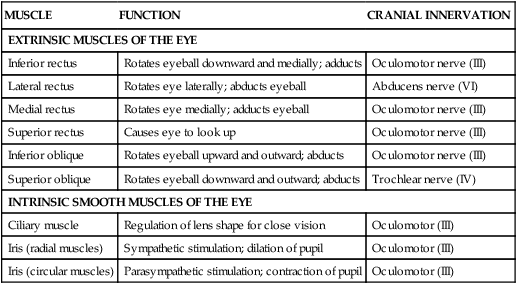

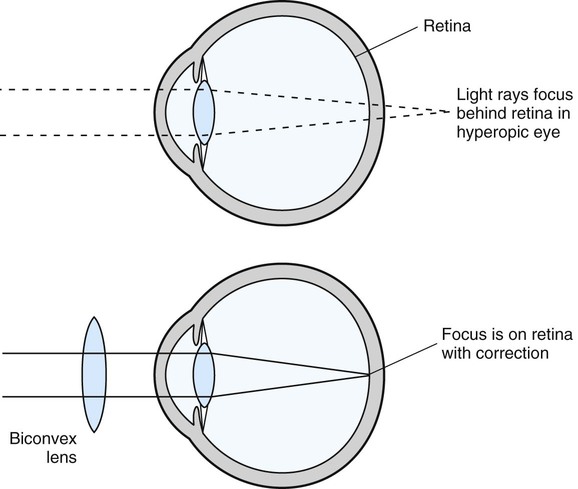

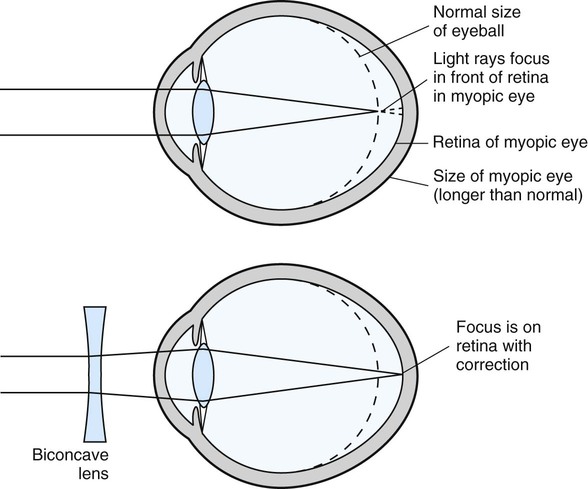

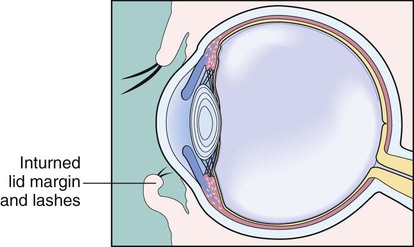

After studying Chapter 5, you should be able to: 1. Describe the processes of vision and hearing. 2. Recall and define the four main refractive errors of vision. 3. Compare the pathology and etiology of nystagmus with that of strabismus. 4. Explain the importance of early treatment of glaucoma. 5. Name the possible causes of conjunctivitis. 6. List the causes of cataracts. 7. Explain the susceptibility of diabetics to diabetic retinopathy. 8. Characterize the visual disturbance caused by macular degeneration. 9. Explain why early diagnosis and treatment are important in retinal detachment. 10. Compare conductive hearing loss with sensorineural hearing loss. 11. List the symptoms of otitis externa. 12. Describe the treatment of otitis media. 13. Explain the signs and symptoms of Ménière’s disease. 14. Describe the symptoms of benign positional vertigo. 15. Discuss the importance of preventing sensorineural hearing loss. Major organs of special senses include the eye and the ear. The functional process of vision takes place in the presence of light in the following manner: (1) an image is formed on the retina; (2) the rods and cones are stimulated; and (3) nerve impulses are conducted to the brain. The area of the brain that involves the sense of sight is much larger than the areas involved with the other senses. Before discussing the pathophysiology of ocular disease, a review of the complex structure of the eye is in order (Figure 5-1). The sclera, the outermost layer, consists of tough fibrous connective tissue that is visible as the white of the eye. Attached to the sclera are the six extrinsic muscles that move the eye (Table 5-1). The cornea, the colorless transparent structure on the front of the eye, is continuous with the sclera on the anterior aspect of the globe. This transparent structure uses its curvature to help focus the light rays as they enter the eye. TABLE 5–1 The intrinsic muscles of each eye respond to light levels and change the size of the pupil to regulate the amount of light that enters the eye and reaches the retina. Each eye has six extrinsic muscles that control the movements of the eye; these muscles pull on the eyeballs, making the two move together to converge on one visual field (see Table 5-1). Normally, the eyes work together in unison, so an assessment of the functioning of these muscles often is included in a neurologic assessment. Table 5-2 summarizes the functions of the major parts of the eye. TABLE 5-2 Functions of the Major Parts of the Eye • Lesions/sores in or around the eyes • Unequal pupils, sudden loss of vision, persistent pain or other symptoms associated with eye injury Diagnostic tests for eye diseases and conditions include the following: • Eye charts, such as the Snellen chart, to measure visual acuity • Visual field tests to check central and peripheral vision • Tonometry to measure intraocular pressure • Eye cultures to identify viral or bacterial infectious agents • Dilation to directly view the posterior structures of the eye, including the retina and optic nerve • Electronystagmography (ENG) to measure the direction and degree of nystagmus • Electroretinography to measure electric activity of the retina in response to flashing of light • Fluorescein angiography to assess the vasculature of the eye Hyperopia (farsightedness) occurs when light that enters the eye is focused behind the retina rather than on the retina, which requires refocusing by the internal lens or the use of an external corrective lens to reposition the viewed object on the retina to sharpen the image. With this condition, near vision is particularly impaired. Hyperopia occurs when the eyeball is abnormally short as measured from front to back (Figure 5-2). Myopia (nearsightedness) is the result of light rays entering the eye being focused in front of the retina, causing blurred vision. Near objects can be seen clearly, but distant objects are blurry, and the image being viewed cannot be sharpened by the internal lens of the eye. Myopia occurs when the eyeball is abnormally long as measured from front to back (Figure 5-3). Keratitis often is caused by an infection resulting from the herpes simplex virus. This is especially likely when the keratitis is preceded by an upper respiratory infection (URI) with facial cold sores (see “Herpes Simplex [Cold Sores]” section in Chapter 8). Certain bacteria and fungi also can be responsible for keratitis. Contact lens wear substantially increases the risk of bacterial keratitis, especially for those who sleep with lenses in place. Other forms of keratitis can be caused by corneal trauma, or exposure of the cornea to dry air or intense light, as occurs during welding. Cultures may be taken to identify the causative organism. Blepharitis is inflammation of the margins of the eyelids involving hair follicles and glands. The ulcerative form of blepharitis is usually the result of a staphylococcal infection. Nonulcerative blepharitis can be caused by allergies or exposure to smoke, dust, or chemicals. This condition also can be secondary to seborrhea of the eyelid’s sebaceous glands, and often the patient has a history of repeated hordeolum (see “Hordeolum [Stye]” section) and chalazia (see “Chalazion” section). In the case of entropion, the eyelid margins (more often the margin of just the lower lid) turn inward, causing the lashes to rub the conjunctiva (Figure 5-8). The patient has the sensation of a foreign body in the eye, tearing, itching, and redness. Chronic irritation of the conjunctiva may cause conjunctivitis (see “Conjunctivitis” section). Entropion can also damage the cornea, causing epithelial defects and vision problems if not corrected. Conjunctivitis can be either unilateral or bilateral and is common. Symptoms include redness, swelling, foreign body sensation and itching of the conjunctiva. The eyes may tear excessively and be extra sensitive to light. In the case of infectious conjunctivitis, a discharge ranging from watery to hyperpurulent can be present. This condition (pink eye) is highly contagious (Figure 5-11).

Diseases and Disorders of the Eye and Ear

Disorders of the Eye

Functioning Organs of Vision

MUSCLE

FUNCTION

CRANIAL INNERVATION

EXTRINSIC MUSCLES OF THE EYE

Inferior rectus

Rotates eyeball downward and medially; adducts

Oculomotor nerve (III)

Lateral rectus

Rotates eye laterally; abducts eyeball

Abducens nerve (VI)

Medial rectus

Rotates eye medially; adducts eyeball

Oculomotor nerve (III)

Superior rectus

Causes eye to look up

Oculomotor nerve (III)

Inferior oblique

Rotates eyeball upward and outward; abducts

Oculomotor nerve (III)

Superior oblique

Rotates eyeball downward and outward; abducts

Trochlear nerve (IV)

INTRINSIC SMOOTH MUSCLES OF THE EYE

Ciliary muscle

Regulation of lens shape for close vision

Oculomotor (III)

Iris (radial muscles)

Sympathetic stimulation; dilation of pupil

Oculomotor (III)

Iris (circular muscles)

Parasympathetic stimulation; contraction of pupil

Oculomotor (III)

STRUCTURE

FUNCTION

Sclera

External protection

Cornea

Light refraction

Choroid

Blood supply

Iris

Light absorption and regulation of pupillary width

Ciliary body

Secretion of vitreous fluid; in addition, its smooth muscles change the shape of the lens

Lens

Light refraction

Retinal layer

Light receptor that transforms optic signals into nerve impulses

Rods

Means of distinguishing light from dark and perceiving shape and movement

Cones

Color vision

Central fovea

Area of sharpest vision

Macula lutea

Blind spot

External ocular muscles

Movement of the globe

Optic nerve (cranial nerve II)

Transmission of visual information to the brain

Lacrimal glands

Secretion of tears

Eyelid

Eye protection

Refractive Errors

Hyperopia (Farsightedness)

Description

Myopia (Nearsightedness)

Description

Strabismus

Disorders of the Eyelid

Hordeolum (Stye)

Keratitis

Etiology

Blepharitis

Description

Etiology

Entropion

Description

Symptoms and Signs

Conjunctivitis

Symptoms and Signs

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree