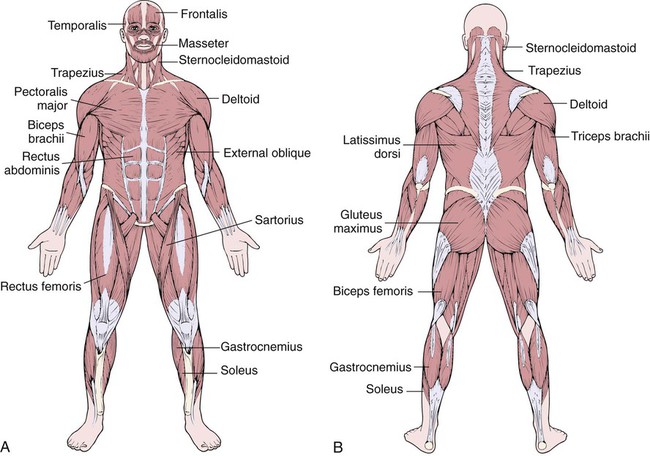

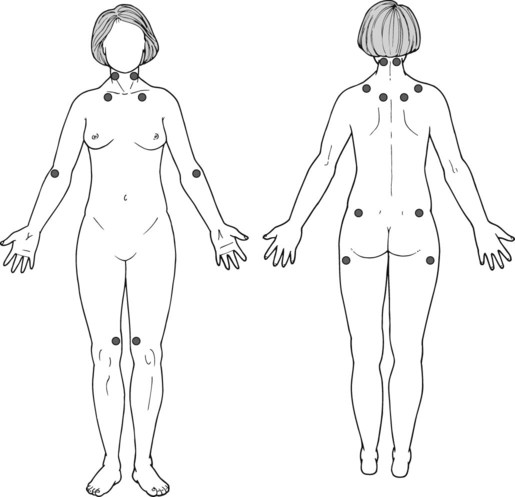

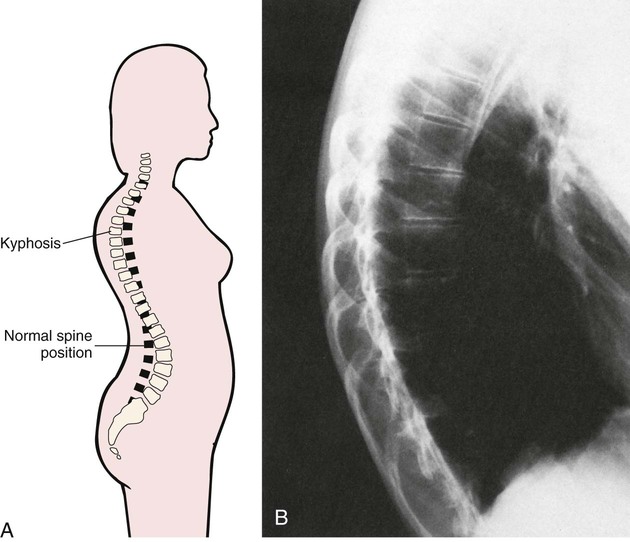

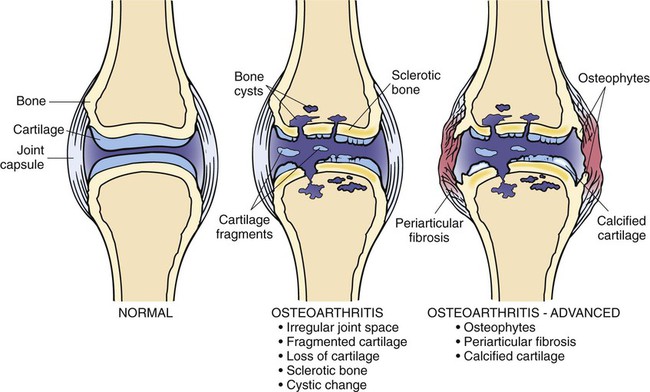

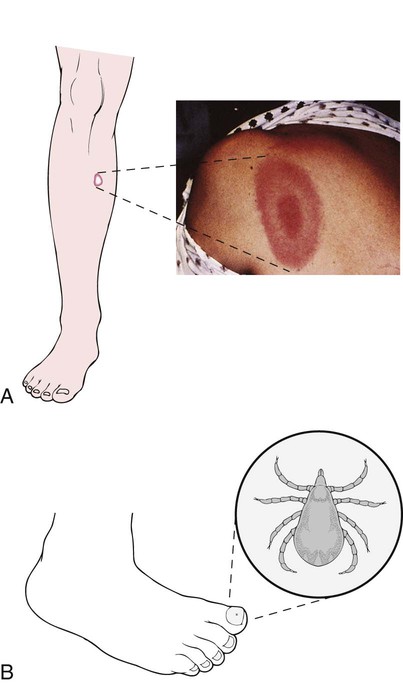

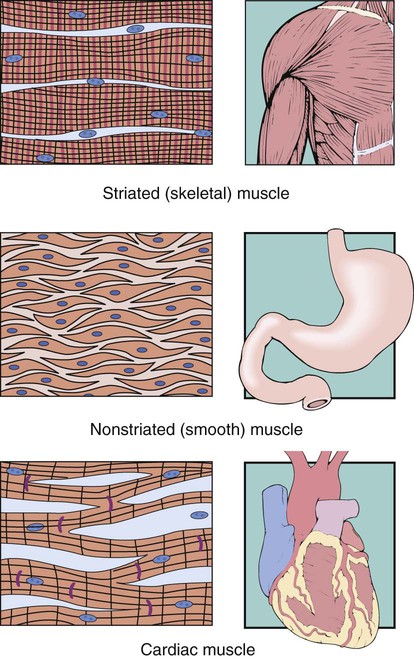

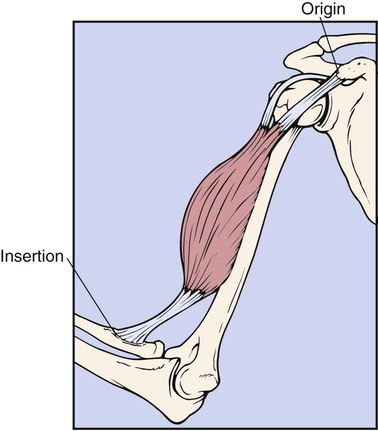

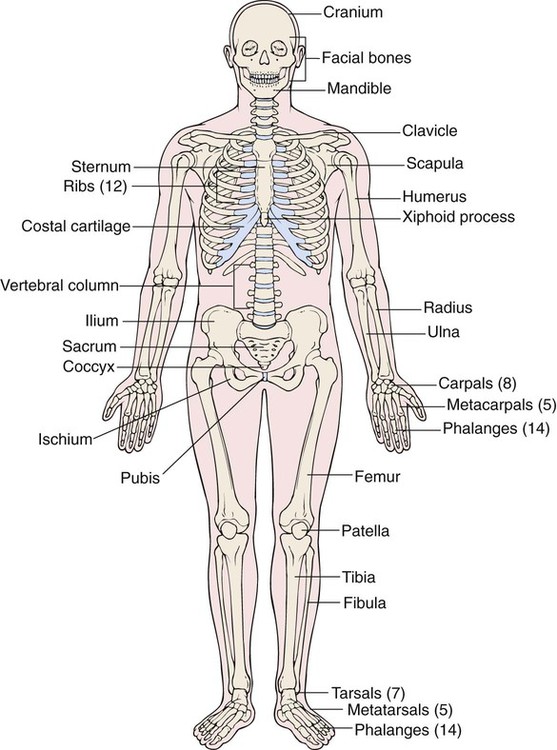

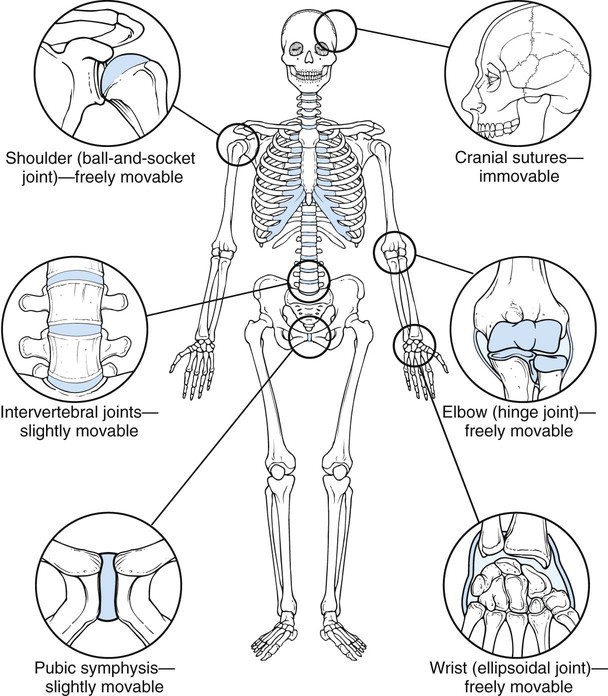

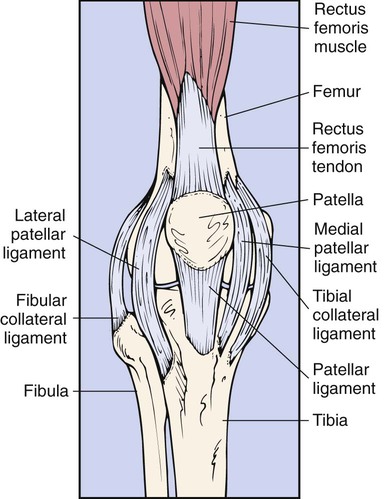

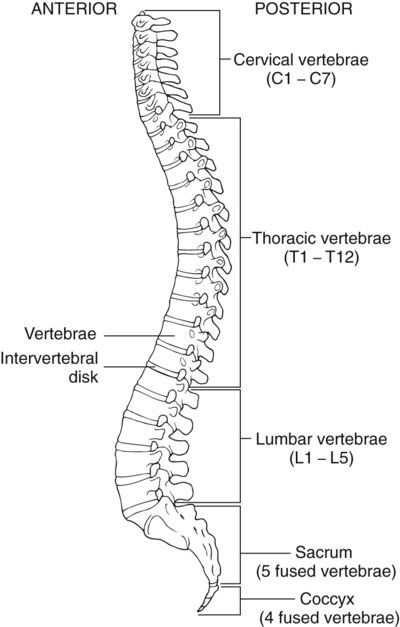

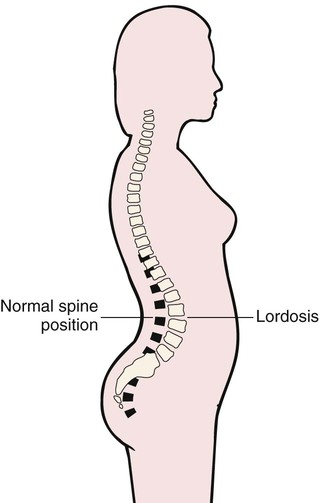

After studying Chapter 7, you should be able to: 1. List the functions of the normal skeletal system. 2. Distinguish among the pathologic features of lordosis, kyphosis, and scoliosis. 3. Describe the signs and symptoms of the most common form of arthritis. 4. Explain the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease. 5. Describe the treatment of bone tumors, both benign and malignant. 6. Discuss the specifics of a physical examination when fibromyalgia is suspected. 7. Explain why joint disability results from gout. 8. Describe the clinical picture of osteomyelitis and explain how it is treated. 9. Describe the disability that results from advanced osteoporosis. 10. Explain why osteomalacia is termed a metabolic bone disease. 11. Distinguish between hallux valgus and hallux rigidus. 12. Differentiate between a strain and a sprain. 13. Explain the importance of proper treatment of dislocations. 14. Describe the cause of shin splints. 15. List some factors that contribute to the development of plantar fasciitis. 16. Explain how torn meniscus is treated. All muscles are composed of a basic cellular unit called the muscle fiber, which is made of protein. Muscles of the skeleton are collections or masses of tissue that cover bones, providing bulk to the body while also helping to hold body parts together and to move joints (Figure 7-1). These skeletal muscles make up approximately 40% of the total body mass. All movement, including the movement of the body itself and of the internal organs, is performed by muscle tissue. The three types of muscle tissues, defined histologically, are striated (skeletal), nonstriated (smooth), and cardiac (Figure 7-2). Muscle is also classified as either voluntary or involuntary. Skeletal muscle is voluntary and is under the control of the conscious mind; this includes the muscles used to move the extremities, which have been stimulated by nerves at the request of the brain. The point of attachment of a muscle to a stationary bone is referred to as the origin of the muscle, and the point of attachment to a bone that is moved by the muscle is referred to as its insertion (Figure 7-3). When a muscle contracts, the insertion moves toward the origin. Smooth muscle and heart muscle are involuntary and function without conscious control or awareness. Examples are the muscles of the intestines that move the bowels and cardiac muscles, which cause the beating of the heart. The skeletal system is composed of 206 bones. These serve to provide an important support system for the many body parts, enabling a person to assume various body postures (Figure 7-4). In coordination with muscles and joints, bones assist body movement. Joints, or articulations, are body structures in which bones are joined or the surfaces of two bones come together for the purpose of creating motion. With the help of ligaments, joints hold bones firmly together yet allow movement between them. Joints are classified by the type of material found between the bones: fibrous, cartilaginous, and synovial. Joints also are classified according to the degree of movement (Figure 7-5) they can make. Immovable (synarthrodial) joints (e.g., suture joints between the bones of the skull) are connected by fibrous tissue; slightly movable (amphiarthrodial) joints (e.g., the intervertebral joints and the pubic symphysis) are connected by cartilage; and freely movable (diarthrodial) joints (e.g., the knee and the elbow) are called synovial joints because they are lined with the fluid-producing synovial membrane. Also within synovial joints are bones, cartilage that covers the ends of the bones, ligaments that hold bones together, a joint capsule containing synovial fluid, blood and lymph vessels, and nerves. Ligaments are tough, dense, fibrous bands of connective tissue that hold bones together, either around a joint capsule (e.g., the hip joint) or across a joint (e.g., the knee [Figure 7-6]). They allow movement in some directions while restricting it in other directions, thereby providing some stability. Injury to ligaments can occur in several ways; they can be overstretched and sustain partial or complete tears (sprains) or be torn completely loose from their attachment to a bone, an injury called an avulsion. Tendons are tough strands, or cords, of dense connective tissue. They serve to attach muscles to bones and other parts (see Figure 7-6). Tendons are nonelastic and are capable of withstanding great forces from contracting muscles without sustaining damage. Injury to a tendon is called a strain. Also necessary for the functioning of the musculoskeletal system are the bursae, closed sacs or cavities of synovial fluid lined with a synovial membrane. Positioned between tissues such as tendons, bones, and ligaments, bursae make it possible for these tissues to glide over each other without creating friction. Bursae are located in the shoulder (see Figure 7-15), elbow, and knee joints. Another substance found throughout the musculoskeletal system is a fibrous protein called collagen. Collagen constitutes 30% of the total body protein and is the major supporting element, or glue, in the connective tissues between the cells that holds them together. In adults, collagen makes up one third to one half of the total body protein (see “Connective Tissue Diseases” section in Chapter 3). There are no specific laboratory or imaging studies that can be used to diagnose fibromyalgia. Testing is done only to exclude other causes of muscle pain. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia is made purely on clinical grounds based on the thorough history and physical examination to reveal widespread tenderness and pain or aching commonly in at least 11 of 18 specific tender points (Figure 7-7). Usually found on both sides of the body in all four quadrants, the widespread pain should exist for a minimum of 3 months before being diagnosed as fibromyalgia. The 18 sites of tender points cluster in the regions of the neck, shoulders, chest, hips, knees, and elbows. Additionally, the occurrence of sleep disorders helps to confirm the diagnosis. The lumbar spine normally curves inward. This normal anterior curve of the lumbar spine can become exaggerated by a variety of conditions. Excessive inward curvature, or lordosis, occurs as the person compensates for added abdominal girth caused by pregnancy, obesity, or large abdominal tumors. Lordosis also can occur developmentally for unknown reasons. Lordosis may cause no symptoms, or the patient may experience low back pain because of strains on the muscles and ligaments. As compared with normal spine posture (Figure 7-8), lordosis results in a protruding abdomen and buttocks and an arched lower back (Figure 7-9). Kyphosis, an excessive posterior curve of the thoracic spine, often has an insidious onset and is asymptomatic until the hump becomes obvious. As the curve progresses, the patient may begin to experience mild pain, fatigue, tenderness along the spine, and decreasing mobility of the spine. The shoulders appear rounded, and the head protrudes forward (Figure 7-10, A). Kyphosis that occurs in very young children has no specific cause and is believed to be developmental. Adolescent kyphosis usually is related to Scheuermann’s disease, a degenerative deformity of the thoracic vertebrae (Figure 7-10, B). Additional disease processes that contribute to the occurrence of kyphosis include tumors or tuberculosis of the vertebral bodies and ankylosing spondylitis. Collapse of vertebrae from the weakened bone of osteoporosis is often responsible for the hunchback that develops in the older person, particularly the postmenopausal woman. Wearing away of the anterior portion of the vertebrae in a wedge type of manner (anterior wedging) or deterioration of the vertebrae, from whatever cause, results in the excessive curvature with kyphosis. Visual inspection of the spine discloses the excessive curve in the thoracic region. Radiographic films and bone scans document the concave curvature of the thoracic spine along with the wedging of the anterior aspect of the vertebral bodies (see Figure 7-10, B). Older patients with osteoporosis have a loss of bone density. (M41.00-M41.9 = 55 codes of specificity) Q67.5 (Congenital deformity of spine) Q76.3 (Congenital scoliosis due to congenital bony malformation) Q76.425 (Congenital lordosis, thoracolumbar region) Q76.426 (Congenital lordosis, lumbar region) Q76.427 (Congenital lordosis, lumbosacral region) Q76.428 (Congenital lordosis, sacral and sacrococcygeal region) Scoliosis, a lateral curvature of the spine, often has an insidious presentation, possibly going unnoticed for years before detection. In women, for example, the first indication is often unequal bra strap lengths. The patient, usually an adolescent female, reports back pain, fatigue, and sometimes shortness of breath with exertion. Observation of the back reveals a lateral curve of the spine, one shoulder higher than the other, one scapula more prominent than the other, one hip higher than the other, and when the patient bends over, an enlarged muscle mass on one side of the back (Figure 7-11). Osteoarthritis, also known as degenerative joint disease or degenerative arthritis, is by far the most common form of arthritis. It develops as a result of normal wear and tear on the joints and is most common in the elderly, being almost universal in those older than 75 years. Osteoarthritis occurs mainly in the large weight-bearing joints, especially the knees and hips (Figure 7-12). There is a tendency for the smallest joints at the ends of the fingers to be affected by spur formation that leads to the classic bony enlargement referred to as a Heberden’s node. To a lesser degree, involvement of the joints of the fingers at the proximal interphalangeal joints (Bouchard’s nodes, Figure 7-13)—wrists, elbows, and ankles—can occur. Degenerative changes in the spinal vertebrae and the joints of the pelvis can lead to abnormal curvature and local pain. Lyme disease can occur in any age group, and no one is immune to the infection. Approximately half of all patients with Lyme disease have a characteristic red, itchy rash with a red circle center resembling the bull’s eye on a target (target lesion) (Figure 7-14, A) early in the illness. Lyme disease can masquerade as arthritis and cause influenza-like symptoms, such as headache, fever, fatigue, joint pain, and general malaise. If the person does not seek medical attention for the symptoms, complications of muscle weakness, paralysis, and neurologic conditions (e.g., learning difficulties, excessive fatigue, and muscle coordination problems) can develop as the bacterium spreads unchecked internally. Encephalitis, gastritis, or carditis may develop in some patients. Lyme disease is caused by a spirochete bacterium, which is transmitted to humans by a bite from a small tick (Figure 7-14, B) that is carried by mice or deer. In the United States, the bacterium is Borrelia burgdorferi. In Europe, the bacterium Borrelia afzelii also causes Lyme disease. The disease is usually transmitted to humans while they are camping or hiking in woods, fields, or other areas that ticks inhabit. After infiltrating the skin, the bacterium can infect internal organs of the body, causing a variety of symptoms, which often leads to delay in making the correct diagnosis. (M71.10-M71.19 = 24 codes of specificity; M71.50-M71.58 = 20 codes of specificity) M70.039 (Crepitant synovitis [acute] [chronic], unspecified wrist) (M70.031-M70.049 = 6 codes of specificity) M70.30 (Other bursitis of elbow, unspecified elbow) (M70.30-M70.32 = 3 codes of specificity) M70.40 (Prepatellar bursitis, unspecified knee) The classic symptoms of bursitis are tenderness, pain when moving the affected part, flexion and extension limitation, and edema at the site of inflammation. The most frequently affected bursae are those of the shoulder (Figure 7-15), elbow, knee, hip, and between the tendons and muscles of the tibia. Point tenderness may be present, in which case the patient actually can point to the spot of greatest tenderness. If bursae are continually or chronically irritated and inflamed, calcifications can develop. In addition, adhesions can occur around an affected bursa, which limits the movement of the tendons. Bursitis can result from continual or excessive friction between the bursae and the surrounding musculoskeletal tissues. Systemic diseases (e.g., gout and rheumatoid arthritis) and infection can lead to the development of bursitis. In addition, repeated trauma from overuse of a joint can cause bursitis (see “Cumulative Trauma” section in Chapter 15).

Diseases and Conditions of the Musculoskeletal System

The Musculoskeletal System

Fibromyalgia

Diagnosis

Spinal Disorders

Lordosis

Symptoms and Signs

Kyphosis

Symptoms and Signs

Etiology

Diagnosis

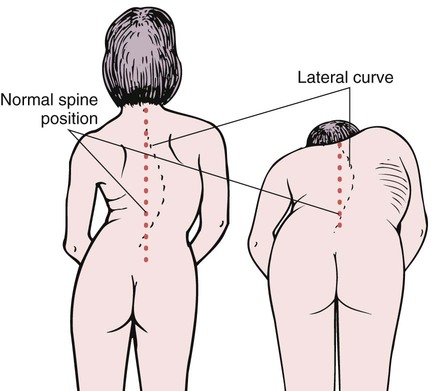

Scoliosis

Description

ICD-9-CM Code 737.30 (Acquired; postural)

ICD-9-CM Code 737.30 (Acquired; postural)

ICD-10-CM Code M41.20 (Other idiopathic scoliosis, site unspecified)

ICD-10-CM Code M41.20 (Other idiopathic scoliosis, site unspecified)

Symptoms and Signs

Osteoarthritis

Symptoms and Signs

Lyme Disease

Symptoms and Signs

Etiology

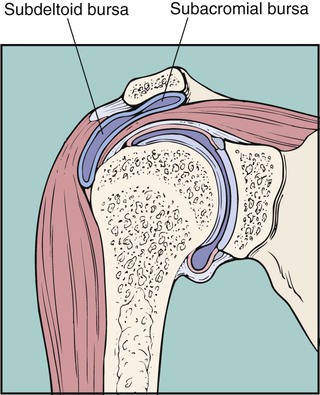

Bursitis

Description

ICD-10-CM Code M71.50 (Other bursitis, not elsewhere classified, unspecified site)

ICD-10-CM Code M71.50 (Other bursitis, not elsewhere classified, unspecified site)

Symptoms and Signs

Etiology

Osteomyelitis