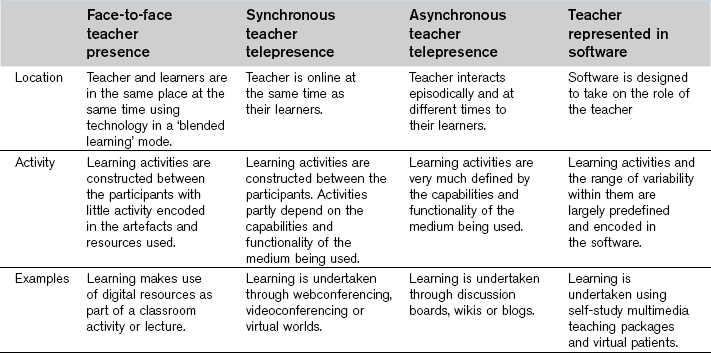

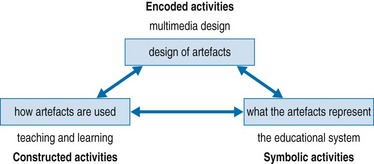

Chapter 27 Educational technologies may be used for many reasons, only some of which directly relate to instruction. Institutions, as well as teachers, are often more interested in other benefits, such as tracking learners, improving administrative efficiency or expanding the reach of their programmes (Ellaway 2011). The shift to more explicitly accountable forms of medical education is supported by digital technologies providing detailed logs of what participants in a programme are actually doing (at least through online institutional systems). Whether this is based on the frequency of learners’ postings to a discussion board or the numbers and mix of their logged patient encounters, knowing who is doing what and when they are doing it may be as important to an institution as the quality of their learners’ educational experiences. This is not to endorse such perspectives, but the medical teacher should be clear as to the drivers in and around the tools they use. See Box 27.1 for some of the key ways the digital can drive and shape education. One defining aspect in designing and using digital media for instructional purposes is to what extent and in what way the teacher is, or is not, co-present with their learners. Teachers often consider classroom and independent study as binary opposites, but new media technologies have blurred this distinction. Table 27.1 sets out a continuum between presence and absence and the different kinds of activities and tools that apply to these different settings. Mitchell (2000) presents the concept of ‘economies of presence’ as the cost–benefit ratio for different kinds of presence, both physical and digital. Despite faculty concerns over poor attendance at lectures, most medical learners continue to seek the most authentic, hands-on, face-to-face encounters they can find. The use of digital media typically does not provide the same experiential richness as embodied experiences and can therefore be perceived as less valuable. Despite this, there are situations where economies of presence lead learners to favour the use of digitally mediated activities. For example, digital media can establish or enhance educational presence when learners and teachers are working at a distance from each other, when learners need to access resources out of hours or when shared activities persist over time and involve many participants. Similarly, groups of learners may work as a collective, using digital tools to pool lecture and research notes and other resources, for instance, in small-group learning activities. Another key construct regarding the use of digital technologies in medical education is ‘activity’. Learning doesn’t happen spontaneously; learners and teachers participate in different educational activities (lectures, PBL, exams, bedside teaching and so on). Table 27.1 shows how different forms of presence work with different forms of educational activity, with face-to-face teaching being typically the most improvised, and ‘computer-as-teacher’ designs the most predefined. We can expand on this to consider three levels of activity: encoded, constructed and symbolic (Ellaway & Davies 2011; see Fig. 27.1). Fig. 27.1 Three activity levels associated with educational technologies (after Ellaway R, Davies D: Design for learning: deconstructing virtual patient activities, Medical Teacher 33(4):303–310, 2011). • The presentation principle involves visuals, audio and video. For instance, a series of multimedia design principles have been identified to guide how encoded activities are presented (Mayer 2009). These are essentially about reducing the ‘cognitive load’ on the learner and are summarized in Box 27.2. Multimedia principles should be applicable to any kind of encoded activity involving onscreen or paper-based materials, including lecture slides, handouts and study guides. • Sequencing is concerned with the order in which different encoded activities are presented (this before that, this after that) and the logic that refines the ordering (this if that, that if not this). Although sequencing has been identified as important to learning (Ritter et al 2007) the role and impact of sequencing are still being explored. Both presentation and sequencing are important, not just to instructional use of digital technologies but to all systems and tools used in medical education. • The alignment between different encoded activities and their ability to support different learning objectives is also important. For instance, if the task in hand is to work through a virtual patient diagnostic pathway, how well does that prepare a learner to make similar decisions in practice? From this perspective we can ask similar questions to those raised with regard to simulation and simulators, such as the validity and the extent to which knowledge and experience transfers to medical practice. While the relationships between a simulator and its real-world equivalent are usually apparent, the same cannot always be said about instructional multimedia. Dormans (2008) identifies three aspects of simulation in digital games that can also be applied to educational technologies in medical education:

Digital medical education

Why use digital?

Presence

Activities

Iconic simulation is concerned with how much a technical artefact mirrors key aspects of the real world. For instance, an online lecture about a particular clinical presentation would arguably be less iconic than a virtual patient, where the learner can make practice decisions and deal with the simulated consequences.

Iconic simulation is concerned with how much a technical artefact mirrors key aspects of the real world. For instance, an online lecture about a particular clinical presentation would arguably be less iconic than a virtual patient, where the learner can make practice decisions and deal with the simulated consequences.

Indexical simulation is concerned with simplification of or abstraction from the real world. For instance, PBL cases or virtual patients are written to exclude what the authors would consider irrelevant details. Only certain choices and outcomes are allowed, typically reflecting the intended learning objectives.

Indexical simulation is concerned with simplification of or abstraction from the real world. For instance, PBL cases or virtual patients are written to exclude what the authors would consider irrelevant details. Only certain choices and outcomes are allowed, typically reflecting the intended learning objectives.

Symbolic simulation is concerned with the arbitrary or non-real representation of the real world. For instance, requiring a learner to interact with a virtual patient using mouse clicks and key presses is more symbolic than physically interacting with a mannequin.

Symbolic simulation is concerned with the arbitrary or non-real representation of the real world. For instance, requiring a learner to interact with a virtual patient using mouse clicks and key presses is more symbolic than physically interacting with a mannequin.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Digital medical education