Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Definition

Non-Hodgkin diffuse lymphoma of large B cells.

Synonyms

Lymphoma, diffuse, histiocytic (Rappaport) (1); Lymphoma, large-cell, cleaved, noncleaved, and immunoblastic (Lukes-Collins) (2); Lymphoma, centroblastic and immunoblastic (Kiel) (3); Lymphoma, large-cell, cleaved, noncleaved, immuno-blastic, and polymorphous (Working Formulation) (4); Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL; Revised European-American Lymphoma Classification; REAL) (5); Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (World Health Organization; WHO) (6).

Epidemiology

In Western countries, DLBCLs constitute the most common, 30% to 40% of adult non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) (4,5,6). Like other types of highly aggressive lymphomas, they account for an even larger proportion of lymphomas in underdeveloped countries and in people with immune deficiencies, particularly acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Forty percent of large cell B-cell lymphomas originate in internal organs, but in patients with AIDS or induced immunosuppression, these tumors may be extranodal in more than 60% of cases (7). It accounts for the vast majority of lymphoma in the central nervous system, testis, and gastrointestinal tract. It is the most common lymphoma in the immunosuppressed. The age range of patients with large-cell lymphomas is wide; they are more common in adults and older persons (with a median age of 70 years), but children are occasionally affected. A slight male preponderance is noted. Large-cell lymphoma of T-cell type, described in the chapter on peripheral T-cell lymphoma (Chapter 74), is far less common in the Western hemisphere than its B-cell counterpart (3,8).

Pathogenesis

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a high-grade aggressive lymphoma that, with modern therapy, is potentially curable (6). The category of DLBCL, as defined in this classification, comprises those lymphomas for which synonyms are listed above and which were considered to be individual entities in earlier classifications. According to the proposals of the REAL classification, and subsequently adopted by the WHO classification, these entities were unified into one category because (a) subclassifying large-cell lymphomas was difficult and resulted in poor reproducibility and (b) all cases of large B-cell lymphomas regardless of nomenclature were treated similarly (5,6). Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is heterogeneous clinically, morphologically, molecularly, and genetically; further subclassification may be necessary as more knowledge is acquired (9,10,11,12).

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma may occur de novo, arising as primary tumors or as the result of progression and transformation of a less aggressive lymphoma of lower grade such as lymphocytic, follicular, or marginal lymphomas (6). The classic example of transformation, known as the Richter syndrome, is the change to DLBCL suffered by approximately 5% of patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) (13,14).

The heterogenous group of DLBCL includes, according to the WHO classification of 2001, five variants: centroblastic, immunoblastic, plasmablastic, anaplastic, and T-cell rich (6). In addition, three subtypes exist— mediastinal, intravascular, and effusion lymphomas—which, although infrequent, can be considered as distinct pathologic entities (15). The main, most common variants are centroblastic and immunoblastic, which differ by gene expression profiles as shown by DNA microarray as well as by clinical behavior (9,10,11,12,15). The centroblastic type is more frequent and has a better prognosis. Because the centroblastic type has a better response to therapy and a longer survival, numerous studies have been devoted to investigate the molecular mechanisms of the Richter transformation. Several studies have indicated that DLBCL arising by the transformation of B-CLL develop through clonal evolution. In such cases, DLBCL may be clonally identical to the B cells of the other low-grade lymphoma that preceded it. Studies of molecular pathogenesis of DLBCL have suggested that many cases underwent an aberrant activity of somatic hypermutations, which may explain why in DLBCL we do not find a dominant translocation but rather a diversity of lymphoma subtypes (12,16).

Centroblastic lymphomas, according to concepts introduced by Lukes and Collins (2) and Lennert and Mohri (3), originate from the cells of the germinal center including the centrocytes (cleaved) and centroblasts (noncleaved). They may occur de novo or follow treated or untreated lymphomas of a lower grade (17). In 20% to 30% of cases, DLBCLs evolve from a preceding follicular lymphoma (FL) (17). Others result from the transformation of B-cell, marginal lymphomas and even Hodgkin lymphoma, particularly the nodular lymphocyte-predominant type (13,17,18,19).

Immunoblastic lymphomas (IBL) are composed of activated lymphocytes (also known as immunoblasts) and show characteristic features of immunoglobulin (Ig) synthesis and plasmacytic differentiation (20,21,22). They often arise in extranodal locations, and patients frequently have a history of an immune disorder. Immunoblastic lymphomas of B- and T-cell type were described originally (20,21,22). In the recent classification, the immunoblastic lymphomas of B-cell type are considered to be a variant of DLBCL, whereas the immunoblastic lymphomas of T-cell type are included in the category of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. They are usually located in lymph nodes and have a poor prognosis (8,21,23). In a series of patients with IBL, prior immune disease was noted in 36% of IBLs of B-cell type and 16% of IBLs of T-cell type, whereas a lymphoproliferative condition was recorded in 26% of IBLs of T-cell type and 13% of IBLs of B-cell type (8). Among the autoimmune diseases that have been noted to precede IBL are systemic lupus

erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto thyroiditis, Sjögren syndrome, celiac disease, and various drug allergies (24,25). Benign or low-grade lymphoproliferative conditions that have preceded IBL are angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and well-differentiated lymphocytic lymphoma (26,27).

erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto thyroiditis, Sjögren syndrome, celiac disease, and various drug allergies (24,25). Benign or low-grade lymphoproliferative conditions that have preceded IBL are angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and well-differentiated lymphocytic lymphoma (26,27).

Immunoblastic lymphoma has also developed in patients with congenital immune deficiencies and in immunosuppressed recipients of renal transplants (28,29,30,31). Among patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), lymphomas have developed in unprecedentedly high proportions. The vast majority of these were DLBCL and, of these, B-cell IBL accounted for more than 30% in some studies (7,31,32). The presence of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antigens is demonstrated in over 70% of AIDS-associated DLBCL, indicating an etiologic role for the virus (33). The documented relationship between altered immunity and IBL supports the concepts of Lukes and Collins, who first described this lymphoma variant (20,33). In their view, IBL may represent the development of a malignant clone of immunoblasts in immunodeficient organisms exposed to prolonged immunologic stimulation. It may be postulated that a pool of previously EBV-infected B cells is activated in the course of the HIV infection and that multiple genetic lesions occur, which are allowed to progress to lymphoma under the conditions of a failing T-cell surveillance system (31).

Clinical Syndrome

The age distribution of large B-cell lymphomas is bimodal. The largest number of cases occur in persons 65 to 69 years old; a smaller peak in persons 35 to 39 years old mainly represents the high incidence of this type of lymphoma in patients with AIDS (34). The sex distribution is equal, or a slight male predominance may be noted (4).

Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas usually present at a single site, nodal or extranodal, the latter more often affected in cases of immune deficiency. They form a mass that grows rapidly, resulting in bulky tumors and early dissemination (35,36). About 30% of patients have fever, night sweats, or weight loss (“B” symptoms) (37). Bone marrow involvement is less frequent (10% to 20% of cases) than in small cell lymphomas and does not occur before lymph node involvement (38). The peripheral blood is involved only in a terminal phase. Patients who report a previous allergic disorder, autoimmune disease, or lymphoid neoplasm present in more than 60% of cases with advanced disease and systemic symptoms, and 70% already have stage III or IV disease (24,25). Most reported cases have been in elderly patients, who show marked lymphopenia (<1,000/mm3 in 45% of cases), anemia, fever, weight loss, and skin rashes. Hypergammaglobulinemia, monoclonal or polyclonal, is present in 44% of cases (24). Lymph nodes in various locations are involved, either in isolation or in association with visceral lymphomas in intestine, lung, skin, testis, or salivary gland. Not infrequently, the affected organs were the site of the previous disorder. Survival time for untreated patients with IBL is generally short, with a median of 17 months in a study of 35 cases (8). In a retrospective study of 51 cases followed for 14 to 28 years, patients with T-cell IBL fared significantly worse than those with B-cell disease (23). AIDS patients with IBL, usually of B-cell type, succumb even sooner, in 6 to 12 months. Thus, features associated with poor prognosis in DLBCL are high-stage disease, International Prognostic Index Score, high proliferation fractions, BCL-2 expression, overexpression of p53, and particularly an immunoblastic (activated) IBL variant as defined by DNA microarray analysis (10).

Combination chemotherapy has changed the prognosis of patients with aggressive large-cell lymphomas; what was formerly a fatal disease is now in most cases curable (39). In particular, patients with early-stage disease treated with effective chemotherapy and adjuvant radiotherapy are able to achieve long-term disease-free survival (40). The recent addition of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab (Rituxan) to chemotherapy is further improving the prognosis of DLBCL.

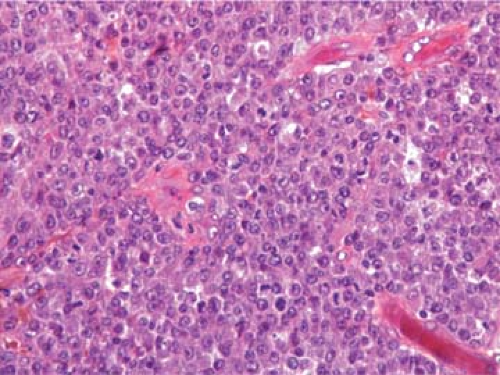

Histopathology

The normal architectural features of the involved lymph nodes, including the follicles and sinuses, are replaced by sheets of large lymphoma cells (Fig. 67.1). Occasionally, the lymph nodes are only partially involved, and the lymphoma cells are aggregated in nodular confluent areas (Fig. 67.2). Such neoplastic nodules differ from lymph node follicles in size (larger), shape (irregular), and the absence of distinct zones and follicular dendritic cells (17). Fine or broad bands of fibrosis may be present. In some cases, the lymphoma cells are dispersed, intermingled with lymphocytes, plasma cells, or histiocytes.

The two main variants of large-cell lymphomas are centroblastic and immunoblastic, as in the Kiel classification (2), or cleaved/noncleaved and immunoblastic, as in the Lukes-Collins classification (2). The infiltrate of lymphoma cells can be monomorphic, or it can be a pleomorphic admixture of large lymphoma cells that include bizarre cells with multilobate nuclei or huge Hodgkin-like nucleoli. The WHO classification recognizes five variants (6,15):

The two main variants of large-cell lymphomas are centroblastic and immunoblastic, as in the Kiel classification (2), or cleaved/noncleaved and immunoblastic, as in the Lukes-Collins classification (2). The infiltrate of lymphoma cells can be monomorphic, or it can be a pleomorphic admixture of large lymphoma cells that include bizarre cells with multilobate nuclei or huge Hodgkin-like nucleoli. The WHO classification recognizes five variants (6,15):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree