Diagnostic Approach to Breast Abnormalities

Helen Krontiras

Heidi Umphrey

Kirby I. Bland

Breast cancer accounts for 26% of all female cancers (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer and in situ cancers). More than 182,960 women were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in 2008 alone, and despite significant strides in the treatment of breast cancer, more than 40,000 women die of the disease each year. The public has become increasingly aware of breast cancer and its prevalence and, as a result, women presenting with breast complaints are anxious about the possibility of being diagnosed with breast cancer. Clinicians evaluating women with breast complaints should provide a comprehensive, efficient, and timely consultation so that anxiety can be relieved by a benign diagnosis or a treatment plan can be instituted promptly should a cancer be diagnosed.

History and Physical Examination

A thorough history and physical examination are essential components of the diagnostic evaluation of a breast abnormality. Key features of the history include details about the presenting symptom, history of previous breast disease, and risk factors for breast cancer including a menstrual history and other contributing past medical history. Initial questions should focus on the presenting symptom, whether it be a mass, nipple discharge, palpable adenopathy, pain, or abnormal imaging. Questions should be asked regarding the length of time the abnormality has been present, associated pain, change in size or texture of the breast over time, and the relationship of the pain or change in size of the breast or mass to the menstrual cycle. Additionally, it is important to ascertain whether the patient has noticed any associated nipple discharge, nipple changes, axillary adenopathy, or skin changes. If the patient reports nipple discharge, it is important to inquire about whether the discharge is spontaneous or happens only with manipulation. A patient may notice staining of spontaneous discharge on her bra or bedclothes.

Identification of risk factors responsible for increasing a woman’s likelihood of developing breast cancer is important in the daily practice of clinicians caring for women. Risk factors for developing breast cancer can be divided into several categories: gender, age, endocrine factors, family history, genetic or inherited factors, and previous breast disease. Female gender is the most common risk factor for breast cancer. Male breast cancer accounts for less than 1% of all breast cancer. A patient’s risk for developing breast cancer increases with age. A woman in the sixth decade has a 1 in 24 chance of developing breast cancer, compared with 1 in 257 for a woman in her third decade. Endocrine risk factors for breast cancer include endogenous estrogen exposure and exogenous exposure to estrogen and progesterone. Early menarche, late menopause, late parity, and nulliparity all increase exposure to endogenous estrogen. In women who have had hysterectomy, whether or not the ovaries have been removed should be documented. It may be difficult to accurately determine the date of menopause, and often questions about menopausal symptoms may be helpful. Recent studies have indicated that long-term hormone replacement therapy with estrogen and progesterone can increase risk for breast cancer.

Previous personal history of breast cancer increases risk for subsequent breast cancer by approximately 0.7% per year. Having had a breast biopsy also increases risk to a much smaller extent, and this risk is further elevated if the pathologic results returned atypical hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ. Table 1 lists the pathologic classification of benign breast disease and the risk associated with each category. A family history of breast or ovarian cancer consistent with genetic or inherited breast cancer significantly increases risk. A history of prior thoracic irradiation in women in their second and third decades of life carries a risk of subsequent breast cancer of approximately 35% by age 40. A summary of risk factors is listed in Table 2. It is important to note, however, that 60% of women with newly diagnosed breast cancer have no identifiable risk factors. Thus, the decision to evaluate a breast abnormality should not depend on the presence or absence of risk factors. Moreover, the presence or absence of risk factors does not influence the probability that a breast abnormality is malignant.

The physical examination should be performed with respect for patient privacy and comfort without compromising the complete evaluation. The examination begins with inspection. The breasts are visually observed and compared with the patient upright for any obvious masses, asymmetries, and skin changes. The nipples are inspected for the presence of retraction, inversion, or excoriation. The patient is then asked to lift her arms for a more careful inspection of the lower half of the breasts. This maneuver also highlights any subtle retraction that is not readily visible with the arms relaxed. Palpation of the regional nodes should follow to include the cervical, supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary nodal basins. Finally, the breast is palpated in a systematic manner with the patient upright with arms relaxed and supine with the ipsilateral arm raised above the head.

Table 1 Pathologic Classification of Benign Breast Disease and the Risk Associated with Each Category | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A dominant mass is defined as being three-dimensional, distinct from surrounding

tissues, and asymmetric relative to the other breast. True masses will persist throughout the menstrual cycle. If a dominant mass is identified, it should be measured, and its location, mobility, and character should be documented in the medical record. Diagnosis should not be delayed. If uncertainty remains regarding the significance of an area of nodularity in the absence of a dominant mass in a premenopausal woman, a repeat examination at a different point in the menstrual cycle may clarify the issue.

tissues, and asymmetric relative to the other breast. True masses will persist throughout the menstrual cycle. If a dominant mass is identified, it should be measured, and its location, mobility, and character should be documented in the medical record. Diagnosis should not be delayed. If uncertainty remains regarding the significance of an area of nodularity in the absence of a dominant mass in a premenopausal woman, a repeat examination at a different point in the menstrual cycle may clarify the issue.

Table 2 Risk Factors for Breast Cancer | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In patients who present with nipple discharge, the nipple discharge is often elicited during palpation of the breast. The character, color, and location of the discharging duct or ducts should be documented. If the discharge is not grossly bloody, a Hemoccult test may be used to detect occult blood. Pathologic discharge, which is defined as unilateral, uniduct, spontaneous, and/or bloody discharge, should be evaluated with surgical duct excision.

Breast cancer is very uncommon in men, accounting for less than 1% of all breast cancers. The most common breast problem in men is gynecomastia. Gynecomastia is a benign hypertrophy of breast tissue. In older men, the hypertrophy is often unilateral. The patient usually presents with a discoid mass symmetrically placed beneath the areola, which may be tender to palpation. There are myriad benign causes of gynecomastia. Many medications are associated with gynecomastia. Gynecomastia is easily distinguished from breast cancer in that breast cancer is asymmetrically located beneath or next to the areola, and may be fixed to the overlying dermis or the pectoral fascia. If breast cancer is suspected, imaging followed by biopsy should be pursued.

Imaging

Patients referred from another facility should provide the actual radiographic images so that the consulting surgeon may examine the films as part of the complete patient evaluation. Films of inadequate quality should be repeated. Additional images should be performed as necessary depending on the specific complaint.

Mammography

Screening mammography is used to detect cancer in asymptomatic women when cancer is not suspected. Diagnostic mammography is used to evaluate patients with breast symptoms or complaints, such as nipple discharge or a palpable mass; patients who have had abnormal results on screening mammography; or patients who have had breast cancer treated with breast conservation therapy. The diagnostic examination is tailored to the individual patient’s specific abnormality. The radiologist is present on site during performance of diagnostic mammography to facilitate the problem-solving process.

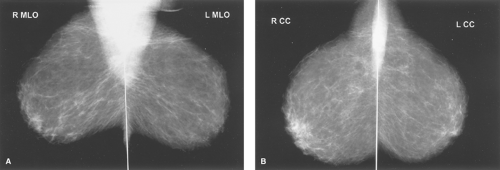

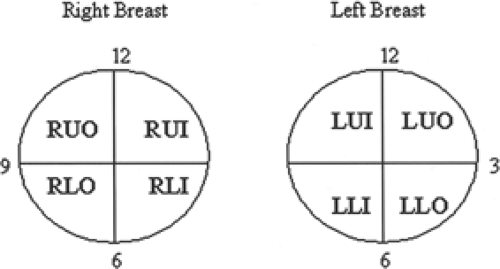

Screening or diagnostic mammography consists of at least two standard views: craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique (Fig. 1). These views demonstrate fibroglandular breast tissue. Right and left views are examined side by side so that asymmetries can be observed. The images are also examined for areas of microcalcifications. A magnifying glass may be necessary for a thorough evaluation. The description of the location of the abnormalities should be indicated based on a quadrant or clock face (with the physician facing the patient) (Fig. 2).

After analyzing the mammographic images, radiologists classify findings into a final assessment category. The Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) final assessment classification was developed by the American College of Radiology to standardize mammographic reporting. The BIRADS classification is listed in Table 3. Follow-up recommendations are made

based on the final assessment category. BIRADS 0 or “incomplete” final assessments require additional imaging to resolve or define an abnormality seen on screening examinations. Additional views may include any number of alternate angles or positions. Spot compression may be used to differentiate an area of summated breast tissue from an abnormal lesion. Magnification views may be used to more clearly evaluate microcalcifications. These techniques may also be used together.

based on the final assessment category. BIRADS 0 or “incomplete” final assessments require additional imaging to resolve or define an abnormality seen on screening examinations. Additional views may include any number of alternate angles or positions. Spot compression may be used to differentiate an area of summated breast tissue from an abnormal lesion. Magnification views may be used to more clearly evaluate microcalcifications. These techniques may also be used together.

Table 3 Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System Classification: Final Assessment Categories | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Most mammographically visible cancers present as masses, calcifications, architectural distortion, or a combination of the three. Masses and calcifications account for about 90% of all breast cancers. A mass is a space-occupying lesion that can be detected in two projections. If a finding is only seen on one projection, it is referred to as a density. A density may or may not prove to be a real finding after directed diagnostic imaging. Masses are characterized by their shape, margin, density, and associated microcalcifications to determine the probability of malignancy.

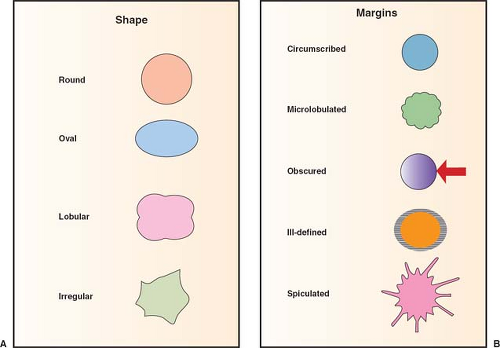

The shape of a mass can be described as round, oval, lobulated, or irregular (Fig. 3). Round or oval masses are usually benign. Masses that are irregular imply a greater probability of malignancy. Lobulated masses suggest an infiltrative growth pattern that may be suggestive of malignancy. Similarly, margin assessment is important because of the infiltrative nature of most breast cancers. Margins can be described as circumscribed, microlobulated, obscured, indistinct, or spiculated. A circumscribed margin that sharply delineates a mass from the surrounding tissue is commonly a benign finding, as seen in a fibroadenoma or a cyst. A

mass with spiculated or stellate margins is suspicious for malignancy (Fig. 4).

mass with spiculated or stellate margins is suspicious for malignancy (Fig. 4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree