GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Diagnostic Criteria

- Patients must meet ONE of the following criteria to be diagnosed with diabetes1,12:

- FPG (fasting plasma glucose) of ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L). Fasting is defined as no caloric intake for at least 8 hours. Confirmation with a second measurement is advised.

- Symptoms of hyperglycemia and a random plasma glucose of ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L). Classic symptoms of hyperglycemia include polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss.

- OGTT (oral glucose tolerance test) 2-hour plasma glucose of ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L). The patient should receive a glucose load containing 75 g of anhydrous glucose dissolved in water.

- Hemoglobin A1C (A1C) ≥ 6.5%.12

- FPG (fasting plasma glucose) of ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L). Fasting is defined as no caloric intake for at least 8 hours. Confirmation with a second measurement is advised.

- Official diagnostic criteria differentiating the two types of diabetes are lacking. A history of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), low or absent C-peptide, and/or the presence of autoantibodies characterize T1DM. Mild hyperglycemia at presentation, a history of GDM, and/or obesity characterize T2DM.

- Gestational diabetes

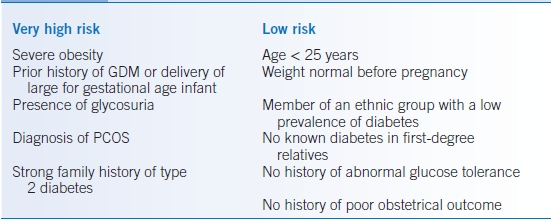

- Women should undergo risk assessment (Table 20-2) and be screened for undiagnosed T2DM at the first prenatal visit using standard diagnostic criteria.12

- Women without a diagnosis of diabetes or positive diagnostic test in the first trimester should undergo a 2-hour, 75-g glucose OGTT at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation.10

- Women with a history of GDM have a higher risk of developing T2DM, so screening for T2DM should occur at 6 to 12 weeks postpartum and every 3 years thereafter.

- Women should undergo risk assessment (Table 20-2) and be screened for undiagnosed T2DM at the first prenatal visit using standard diagnostic criteria.12

TABLE 20-2 Assessing Risk for Gestational Diabetes

GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome.

TREATMENT

- Patients should receive care from a physician-coordinated team including, but not limited to, physicians, certified diabetic nurse educators, dietitians, pharmacists, and mental health professionals with expertise in diabetes.

- All treatment plans should emphasize the role of the patient as an integral component of care with emphasis on self-management education.

- In developing a management plan, consideration should be given to the patient’s age, school/work schedule, physical activity, eating patterns, social situation and personality, cultural factors, and other medical conditions.

- All treatment recommendations should be individualized and based on life expectancy, comorbidities, cognitive abilities, risk of hypoglycemia, and glucose-lowering effectiveness.13

- In T2DM, a number of modifiable environmental factors play a role in disease development. Interventions that target obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, and nutrition have been shown to have a beneficial effect on hyperglycemia, lowering A1C by 0.25% to 2.9%.1

Glycemic Goals

- Glycemic control should be assessed by both self-monitoring of capillary blood glucose (SMBG) and periodic A1C testing.12

- Data have shown that targeting the following goals for glycemic control is associated with the lowest risk of long-term complications for both T1DM and T2DM.9,10

- Preprandial capillary BG values between 90 and 130 mg/dL (3.9 to 7.2 mmol/L).

- Postprandial capillary BG values ≤ 180 mg/dL (<10.0 mmol/L).

- A1C targets should be individualized. Tight glycemic control (A1C < 6.5%) is appropriate for patients managed on non–hypoglycemia-inducing therapies, while less tight control (A1C < 7% to 7.5%) may be appropriate for higher-risk patients, including those with CV disease and T2DM patients treated with insulin. Hypoglycemia should be avoided in all patients.

- Preprandial capillary BG values between 90 and 130 mg/dL (3.9 to 7.2 mmol/L).

- Goals for nonpregnant adults should be individualized and may vary based on the following: duration of diabetes, age and life expectancy, comorbid conditions, known cardiovascular disease (CVD) or advanced microvascular complications, hypoglycemia unawareness, and individual patient considerations.

Self-Monitoring of Capillary Blood Glucose

- For patients using noninsulin, non–hypoglycemia-inducing therapy, SMBG should occur daily or less often. Surveillance with pre and postprandial blood glucose is informative, even if done infrequently.

- For patients using basal insulin only, SMBG is recommended twice daily.

- Patients treated with multiple daily insulin injections or insulin pump therapy should perform SMBG four or more times daily. Improved glucose control is observed with greater testing frequency in patients with T1DM.

- Physicians should review records of SMBG at every visit to titrate medical therapy.

- Frequent glucose monitoring and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), used along with intensive insulin regimens, have been shown to be useful in the management of adults with T1DM, especially those with hypoglycemia unawareness and/or frequent hypoglycemic episodes.12

Hemoglobin A1C

- A1C should be measured at least twice annually in patients who have met treatment goals without hypoglycemia.

- A1C should be measured quarterly in patients whose therapy has changed or who have not meet glycemic goals.

- A1C testing does not replace examination of glucose meter downloads or SMBG records. Point-of-care testing for hemoglobin A1C allows for timely decisions on therapy changes.14

- Limitations of hemoglobin A1C testing

- Inaccurate A1C values may result from the following factors: conditions that affect erythrocyte turnover, hemoglobin variants, and recent blood transfusions.

- Does not provide a measure of glycemic variability or hypoglycemia.

- Inaccurate A1C values may result from the following factors: conditions that affect erythrocyte turnover, hemoglobin variants, and recent blood transfusions.

- Other measures of chronic glycemia such as fructosamine are available, but are not widely utilized.

Hypoglycemia

- Hypoglycemia is a common occurrence in patients with T1DM or T2DM treated with insulin or insulin secretagogues.15

- The preferred treatment of hypoglycemia is 15 to 20 g of glucose, although any form of carbohydrate that contains glucose can be used.

- Fats should be avoided acutely because they can delay the acute glycemic response.16

- Patients should be instructed to recheck an SMBG level 10 to 15 minutes after treatment.

- If SMBG shows continued hypoglycemia, the treatment should be repeated.

- Once SMBG returns to normal, the individual should evaluate his or her risk of recurrence, and modify insulin doses or consume additional calories as needed.

- Overtreatment of hypoglycemia can cause rebound hyperglycemia and increase the variability in glucose values.

- If SMBG shows continued hypoglycemia, the treatment should be repeated.

- Severe hypoglycemia is defined as hypoglycemia that requires the assistance of another person and cannot be treated with oral carbohydrate due to patient confusion or unconsciousness.

- Patients with a history of frequent mild hypoglycemia or one episode of severe hypoglycemia should be prescribed glucagon, and caregivers or family members of these individuals should be instructed on proper administration.

- Hypoglycemia unawareness is characterized by repetitive hypoglycemia that results in a deficiency of the protective counterregulatory hormone and autonomic responses.15

- Individuals with hypoglycemia unawareness should have higher glycemic goals temporarily to partially reverse hypoglycemia unawareness and reduce the risk of future episodes.15

Medications

Oral Agents

- Therapy with one agent is recommended for those patients with an A1C < 7.5%. For those with an A1C 7.5% to 9%, two agents offer greater efficacy. Three agents may be needed if the A1C is >9%, or insulin can be considered. In general, additional medications are added to the background regimen of metformin, though changes are often made when insulin is started.17

- As disease progression occurs in T2DM, medications can be used in combinations to achieve glycemic targets.

Metformin

- Doses are 500, 750, 850, or 1,000 mg given 2 to 3 times per day, not to exceed 2,550 mg daily.

- The primary effect is to decrease hepatic glucose output and lower fasting glycemia.

- Therapy with metformin as a single agent will lower A1C by approximately 1% to 1.5%.18

- Metformin is well tolerated in about 80%, tolerated at lower than maximal doses in 10%, and not tolerated in about 10%.

- Metformin is contraindicated in patients with serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dL in men and >1.4 mg/dL in women. Reduced creatinine clearance increases the risk of lactic acidosis in persons taking metformin. Other risk factors for lactic acidosis in which metformin should be discontinued include hypovolemia, serious infection, tissue hypoxia, alcoholism, and severe cardiopulmonary disease.

- Recent studies suggest that metformin is safe at reduced doses until the eGFR falls below 30 mL/minute.19

Sulfonylureas

- Sulfonylureas (SUs) enhance endogenous insulin secretion, and they are similar to metformin in efficacy and lower A1C by approximately 1% to 1.5%.

- The primary adverse effect is hypoglycemia, which can be severe and prolonged, especially in elderly patients or those with liver or renal disease. Patients who are known to skip meals should not take an SU because of an increased risk of hypoglycemia.

- Glyburide (1.25 to 20 mg daily) is associated with the highest risk of hypoglycemia when compared to other SU and is no longer recommended as a first-line antidiabetic agent.

- Other second-generation SUs include glimepiride (1 to 8 mg once daily), glipizide (5 to 40 mg/day, >15 mg/day should be given in divided doses), glipizide extended release (5 to 20 mg once daily), gliclazide (starting 40 to 80 mg once daily to a maximum of 320 mg/day, doses >160 mg must be split bid), and gliclazide modified release (30 to 120 mg once daily). They are the preferred agents of this class of antidiabetic drugs. Gliclazide is not available in the US.

- Weight gain is common after initiation of therapy.

- Although the onset of the hypoglycemic effect is quite rapid with SUs, durability of the glucose-lowering effect is inferior to the use of a thiazolidinedione (TZD) or metformin when used as monotherapy.20

Glinides

- These drugs also stimulate endogenous insulin secretion but bind to a different site within the SU receptor.

- They have a shorter circulating half-life than SU and are administered more frequently.

- Because of their short half-life, they are less likely to cause prolonged hypoglycemia.

- Glinides are a good choice for patients who would otherwise tolerate a SU but who have experienced hypoglycemia because of variable meal times and/or skipped meals.

- Because of their short half-life, they are less likely to cause prolonged hypoglycemia.

- The two currently available glinides are repaglinide and nateglinide.

- Repaglinide (0.5 to 4 mg ac/tid) is almost as effective as metformin or SU at decreasing hemoglobin A1C level by 1.5%, but nateglinide (60 to 120 mg ac/tid) is somewhat less potent.21

- The risk of weight gain is similar to that with most SUs.

α-Glucosidase Inhibitors

- α-Glucosidase inhibitors, acarbose (25 to 100 mg ac/tid), miglitol (25 to 100 mg ac/tid), and voglibose (0.2 to 0.3 mg ac/tid) decrease the digestion and absorption of polysaccharides in the small intestine.22

- These agents lower postprandial glucose without causing hypoglycemia and lower A1C by 0.5% to 0.8%.

- The most common side effects are bloating and flatulence.

- Long-term use of acarbose has been shown to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction.23

Thiazolidinediones

- TZDs are peroxisome proliferator–activated γ-receptor agonists.

- Only pioglitazone (15 to 45 mg daily) is currently available in the US.

- The primary mechanism of action of TZD is to increase the peripheral tissue sensitivity to insulin.

- When used as monotherapy, they have been shown to lower the hemoglobin A1C level by 0.5% to 1.4% and have better durability of effect than metformin or SU.20

- The most common side effects are weight gain and fluid retention. There is also a twofold greater risk of congestive heart failure.24

- Several meta-analyses suggested an increase in risk for myocardial infarction with rosiglitazone.25 In randomized clinical trials, pioglitazone has been neutral or beneficial in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.26

- Other concerning effects of TZDs include an increase in fracture risk and lower bone mineral density, especially in postmenopausal women.27 Pioglitazone has been associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer.28

Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors

- The gut insulinotropic hormones, incretins, include glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP).29 Both hormones are rapidly degraded by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4). DPP-4 inhibitors enhance the effects of GLP-1 and GIP, increasing glucose-mediated insulin secretion and suppressing glucagon secretion.30

- DPP-4 inhibitors lower A1C by 0.6% to 0.9%.29

- Currently, sitagliptin (25 to 100 mg once daily), saxagliptin (2.5 to 5 mg once daily), linagliptin (5 mg once daily) and alogliptin (6.25 to 25 mg once daily) are available in the US. Vildagliptin (50 mg bid or 50 mg once daily when used with a SU) is available in Europe and Asia. All but linagliptin require dosage reduction in moderate to severe renal impairment.

- They are very well tolerated and have few side effects.30

- DPP-4 inhibitors can be used with other oral therapies and with insulin but should not be used with GLP1 receptor agonists.

Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitor

- The mechanism of action of the SGLT2 inhibitors is to inhibit glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubule of the kidney, causing loss of glucose in the urine.31

- Dapagliflozin (5 and 10 mg) and canagliflozin (100 and 300 mg) are available in the US. Both are contraindicated in moderate to severe renal dysfunction.

- The SGLT2 inhibitors lower A1C by 0.7% to 1.2% and can be safely used with other therapies.32

- The major side effects are genital yeast infections, which can occur in 10% to 20% of patients newly treated, and hypovolemia.

Colesevelam

- This bile acid sequestrant has glucose-lowering properties when given in full doses.

- A1C is reduced by 0.4% to 0.6%, along with lowering of low-density lipoprotein (LDL).

Bromocriptine Mesylate

- Bromocriptine lowers glucose by an unknown mechanism.

- The tablets are 0.8 mg, dosed 1.6 to 4.8 mg once daily.

- It may also help with sleep or circadian rhythm.

- Cannot be used in patients who are taking antipsychotic agents.

Noninsulin Injectable Agents

Amylin Agonists

- Pramlintide, a synthetic analogue of the β-cell hormone amylin, has been shown to slow gastric emptying, inhibit glucagon secretion, and decrease postprandial hyperglycemia.33

- Pramlintide is administered subcutaneously before meals.

- The addition of pramlintide to insulin therapy can decrease the A1C by 0.5% to 0.7%.

- The major side effects are gastrointestinal, predominantly nausea, which tends to improve over time. Weight loss is associated with treatment and may be secondary to gastrointestinal side effects.

- Pramlintide is approved for use only as adjunctive therapy with insulin, in patients with T1DM or T2DM taking premeal regular or rapid-acting analogues.

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Agonists

- GLP-1 is a peptide produced by the small intestine that has been shown to potentiate glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and reduce glucagon secretion from alpha cells.34

- Exenatide, a synthetic GLP-1 agonist, is available as a short-acting agent that is administered twice daily (5 or 10 mg) or in a once weekly formulation (2 mg).

- Liraglutide is administered once daily subcutaneously in doses of 0.6 to 1.8 mg.

- GLP-1 agonists lower A1C by 0.5% to 1.6%.

- Additional actions of GLP-1 agonists include suppressing glucagon secretion and slowing gastric emptying.34

- Gastrointestinal side effects, including nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, are common but tend to resolve over time or with dose reduction.

- Weight loss of 1 to 5 kg is observed in patients taking GLP-1 agonist therapy.35

- Pancreatitis risk may increase with use of GLP agonists, but the magnitude is not defined and appears to be small. Also thyroid C-cell tumors were increased in rodents but not in humans.

- Both liraglutide and exenatide can be used with oral antidiabetes therapies except for DPP-4 inhibitors and are approved for use with insulin.

Insulin

- Insulin remains the most effective medication in the treatment of hyperglycemia and should be considered for initial therapy when the A1C is >9%.17

- Insulin is available as human insulin (regular or NPH) or as analogues (lispro, aspart, glulisine, detemir, and glargine). Insulins are generally grouped by their onset and duration of action into rapid acting (lispro, aspart, glulisine), short acting (human regular insulin), intermediate acting (human NPH), or long acting (detemir, glargine).

- Rapid-acting insulin has an onset of about 1 hour, peak activity at about 2 hours, and duration of action of 4 hours.

- Short-acting insulin (e.g., regular) has an onset of 1 to 2 hours, peak activity of 3 to 4 hours, and duration up to 6 hours.

- Intermediate-acting insulin (e.g., NPH) has an onset of about 2 hours, peak at 6 to 8 hours, and duration of action of 12 to 16 hours.

- Long-acting insulins have a nearly flat, peakless profile and duration of action of 16 to 20 hours (detemir) or 22 to 25 hours (glargine).

- Rapid-acting insulin has an onset of about 1 hour, peak activity at about 2 hours, and duration of action of 4 hours.

- Basal insulin, using either intermediate- or long-acting insulin, is often added to oral or GLP-1 therapy.

- Conventional insulin therapy describes the use of one or two injections per day of regular and NPH insulin, sometimes premixed, given in fixed amounts.

- Intensive insulin therapy, also known as multiple daily injection (MDI) or basal-bolus therapy, describes more complex regimens that utilize basal insulin with rapid-acting insulin three or more times daily to cover meals.

Type 1 Diabetes

- The majority of patients with T1DM will be treated with intensive insulin therapy with MDI or an insulin pump.

- Since the arrival of both rapid- and long-acting insulin analogs, intensive glucose control in patients with T1DM is less associated with prolonged hypoglycemia.36

- Both insulin glargine and detemir are long-acting insulin analogs that have very modest peaks of activity, making them ideal to provide a continuous basal insulin level in a T1DM patient.

- Dosing for insulin glargine is typically once daily, but in certain cases, patients may require twice-daily dosing.

- Dosing for insulin detemir is twice daily.

- Dosing for insulin glargine is typically once daily, but in certain cases, patients may require twice-daily dosing.

- The rapid-acting insulins available are insulin lispro, aspart, and glulisine.37

- All have an onset of action within 5 to 15 minutes, peak action at 30 to 90 minutes, and a duration of action of 2 to 4 hours.

- These agents decrease postprandial hyperglycemia.

- They have been shown to reduce the frequency of hypoglycemia when compared with regular human insulin.

- Rapid-acting insulin should be injected immediately before meals, and the doses can be rapidly adjusted to match the hyperglycemia and carbohydrate intake in most T1DM patients.

- All have an onset of action within 5 to 15 minutes, peak action at 30 to 90 minutes, and a duration of action of 2 to 4 hours.

- Most newly diagnosed patients with T1DM can be started on a total daily dose of 0.3 to 0.4 units of insulin/kg/day, although most will ultimately require 0.7 to 0.8 units/kg/day.

- MDI regimens should be designed in collaboration with an endocrinologist, diabetes educator, and nutritionist to clearly match the needs and lifestyle of the individual.

- As a general rule of thumb, approximately half of the total daily dose should be given as a basal insulin, and the remainder is given as short- or rapid-acting insulin, divided before meals.

Type 2 Diabetes

- T2DM patients with persistent hyperglycemia despite oral hypoglycemic therapy may require the addition of insulin to their regimen or the transition to an insulin-based regimen alone.

- Insulin suppresses hepatic glucose production, which may help to improve the effectiveness of the oral agents and keep the patient’s overall hyperinsulinemia to a minimum.38

- Basal insulin, given once bedtime, is a common starting point for insulin therapy.

- A safe starting dose is typically 10 units or 0.2 units/kg.

- This dose should be titrated up to achieve an FPG level of 90 to 130 mg/dL.

- If nocturnal or symptomatic hypoglycemia occurs in patients taking bedtime NPH, the dose should be decreased or the patient should be switched to insulin glargine.

- A safe starting dose is typically 10 units or 0.2 units/kg.

- For most T2DM patients, adding basal insulin to a regimen of oral or GLP-1 hypoglycemic agents is adequate to achieve glycemic goals.

- For patients who no longer respond to oral agents, preprandial boluses are necessary. These patients should be transitioned to an insulin-based regimen with the guidance of an endocrinologist.

- Very insulin-resistant T2DM patients may require high doses of insulin. Humulin U-500 insulin can be helpful, but the therapy should be guided by an endocrinologist with the help of a diabetes educator.

- Treatment targets and regimens should be individualized to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia, avoid unnecessary complexity, and provide the safe use of pharmaceuticals in patients with declining renal, hepatic, cardiac, or cognitive function. Overzealous glucose lowering with a goal of normalization of glucose values has been associated with increased mortality in patients with T2DM and CV risk factors.39

Other Nonpharmacologic Therapies

- Individual psychological and social issues can impair a patient’s ability to adhere to a diabetes treatment regimen.16 Self-management is often limited by attitudes toward the illness, personal expectations, patient’s mood and affect, quality of life, psychiatric history, and financial, social, and emotional resources.

- Indications for referral to a mental health specialist familiar with diabetes management include:

- Noncompliance with medical regimen

- Depression with the possibility of self-harm

- Debilitating anxiety (alone or with depression)

- Indications of an eating disorder

- Cognitive functioning that significantly impairs judgment or self-care

- Noncompliance with medical regimen

- Adjusting treatment regimens to assess barriers to adherence may improve overall quality of care.

Surgical Management

Bariatric surgery may be considered for adults with BMI of >35 kg/m2 and T2DM, if the diabetes is difficult to control with lifestyle and pharmacologic therapy.40 Longer-term concerns of bariatric surgery include vitamin and mineral deficiencies, osteoporosis, and hypoglycemia from insulin hypersecretion, although the latter effect is rare.

Lifestyle/Risk Modification

Diet

- All patients with diabetes and prediabetes should undergo medical nutrition counseling under the guidance of a registered dietician.41

- In overweight and obese individuals, modest weight loss has been shown to reduce insulin resistance and improve glycemic control.42

- Both low-carbohydrate and low-fat calorie-restricted diets may be effective up to 1 year.43

- For patients on low-carbohydrate diets, monitor lipid profiles, renal function, and protein intake and adjust hypoglycemic therapy as needed.

- Both low-carbohydrate and low-fat calorie-restricted diets may be effective up to 1 year.43

- Macronutrient content and distribution should be individualized to achieve desired weight and to account for personal preferences, cultural influences, and the presence of other illnesses.

- Saturated fat intake should be <7% of total calories and trans fat intake should be discouraged.

- Monitoring carbohydrate intake through carbohydrate counting, exchanges, or estimation is a key strategy in achieving glycemic control.

- The recommended dietary allowance for digestible carbohydrate is 130 g/day. This is based on the amount of glucose required for central nervous system function without additional reliance on glucose production from protein and fat stores.41

- Saturated fat intake should be <7% of total calories and trans fat intake should be discouraged.

- Sweeteners and sugar alcohols:

- FDA-recommended nonnutritive sweeteners are acesulfame potassium, aspartame, neotame, saccharin, and sucralose.

- All have been shown to be safe for people with diabetes and women during pregnancy.

- FDA-approved sugar alcohols are erythritol, isomalt, lactitol, maltitol, mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol, tagatose, and hydrogenated starch hydrolysates.

- The use of sugar alcohols may cause diarrhea, especially in children.

- FDA-recommended nonnutritive sweeteners are acesulfame potassium, aspartame, neotame, saccharin, and sucralose.

- Adults with diabetes should limit alcohol intake to <1 drink/day for women and <2 drinks/day for men.

- Vitamins and supplements:

- Routine supplementation with antioxidants (such as vitamins E and C and carotene) is not advised.

- Data on routine chromium supplementation are not conclusive and are not currently recommended.

- Many patients will require added soluble vitamins (B complex), vitamin D, and calcium. Replacement should be individualized.44

- Routine supplementation with antioxidants (such as vitamins E and C and carotene) is not advised.

Activity

- Regular exercise can improve blood glucose, reduce cardiovascular risk, and assist with weight loss.

- Structured exercise regimens in patients with T2DM have been shown to decrease A1C levels independent of changes in BMI.45

- Adults with diabetes should exercise for ≥150 minutes/week.

- Prior to recommending a program of physical activity, physicians should assess risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD). Dynamic screening of asymptomatic diabetic patients is not recommended, so providers should use their clinical judgment for each individual case.

- Carbohydrate intake and medication adjustments will need to be addressed to avoid hypoglycemia, especially in individuals taking insulin and/or insulin secretagogues.

- Vigorous aerobic or resistance exercise may be contraindicated in patients with severe nonproliferative or active proliferative retinopathy due to the risk of triggering vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment.46

- Non–weight-bearing activities such as swimming, bicycling, or arm exercises are typically better tolerated by patients with severe peripheral neuropathy.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

- Influenza and pneumonia are associated with higher mortality and morbidity in people with diabetes.

- Diabetic patients are at increased risk of the bacteremic form of pneumococcal infection and nosocomial bacteremia.47

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends influenza and pneumococcal vaccines for all individuals with diabetes.1

- Influenza vaccine should be administered yearly.

- Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine should be administered to all diabetic patients >2 years of age. A one-time revaccination is recommended for individuals >65 years old previously immunized when they were <65 if the vaccine was administered >5 years ago. Other indications for repeat vaccination include nephrotic syndrome, chronic kidney disease, and immunocompromised states.

- Hepatitis B vaccination is now recommended for persons with diabetes ages 19 to 59 and should be considered for adults ≥60.

- Influenza vaccine should be administered yearly.

COMPLICATIONS

Cardiovascular Disease

- CVD remains the biggest cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes.

- Diabetes is an independent risk factor for CVD, and patients with T2DM typically have concomitant risk factors such as HTN and hyperlipidemia.

- In diabetic patients, aspirin is recommended for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.48

- In previous clinical trials, variable doses have been used, from 75 to 325 mg/day.

- The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends aspirin use when 10-year CVD risk is ≥6% (Framingham score). It should be considered in men >40 years of age, postmenopausal women, and younger patients with CVD risk factors, such as diabetes.48

- The use of clopidogrel in diabetic patients, who are aspirin intolerant or as adjunctive therapy with aspirin, demonstrated a decrease in secondary CVD events.49

Hypertension

- HTN in diabetic patients is a risk factor for both CVD and microvascular complications.

- The diagnostic cutoff for HTN is lower in diabetic patients because of the synergistic effect of high blood pressure and hyperglycemia on CVD. HTN in a diabetic patient is defined as a blood pressure of >130/80 mm Hg.

- Clinical trials have shown that there is a reduction in the incidence of CV events, stroke, and development of nephropathy when lower blood pressure targets are achieved.50,51

- There are no well-controlled trials of nonpharmacologic therapies for the treatment of HTN in patients with diabetes, but given their benefit in nondiabetic patients, the following can be recommended in conjunction with medical therapy:

- Reduce sodium intake.

- Reduce excess body weight.

- Increase consumption of fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products.

- Avoid excessive alcohol consumption.

- Increase activity levels.

- Reduce sodium intake.

- Pharmacologic therapies for lowering blood pressure should include medications that are effective in both controlling HTN and reducing cardiovascular events.

- Inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system are especially useful for the treatment of diabetic patients with HTN and should be considered first-line agents.51

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to reduce CVD outcomes.

- For patients with T2DM and significant nephropathy, ARBs were superior to calcium channel blockers in reducing heart failure.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to reduce CVD outcomes.

- Most patients with HTN and diabetes will require multidrug therapy to reach treatment goals.

- During pregnancy, patients with diabetes should have a target blood pressure goal of systolic blood pressure 110 to 129 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure 65 to 79 mm Hg.52

- Treatment with ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs is contraindicated.

- Antihypertensive drugs known to be safe in pregnancy include methyldopa, labetalol, diltiazem, clonidine, and prazosin.

- Treatment with ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs is contraindicated.

Dyslipidemia

- Many clinical trials have shown benefits of pharmacologic lipid-lowering therapy in patients with T2DM, both for primary and secondary prevention.53

- While many patients with T2DM have metabolic syndrome characteristics of low HDL and high triglycerides, the initial treatment target remains LDL.

- Lifestyle intervention, including medical nutrition therapy, increased physical activity, weight loss, and smoking cessation, may allow some patients to reach lipid goals.

- Nutrition counseling should focus on reducing dietary saturated fat, cholesterol, and transunsaturated fat. Improved glycemic control can improve dyslipidemia in patients with very high triglycerides.

- For most patients with diabetes, the primary goal of therapy is to lower LDL cholesterol level to a target goal of <100 mg/dL (2.60 mmol/L).54 Multiple studies have shown that statins are the drugs of choice for LDL cholesterol lowering.54

- In high-risk patients with a history of acute coronary syndrome or cardiovascular events, therapy with high doses of statins to achieve LDL cholesterol level of <70 mg/dL may further reduce their risk of subsequent events.54 However, the newest guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association focus less on specific numeric goals and more so on the intensity of treatment. Diabetics should receive moderate- to high-intensity statin therapy (see Chapter 11).55

- If the HDL cholesterol level is <40 mg/dL, niacin can be used to raise the HDL cholesterol level, but there was no benefit on CV outcomes.

- The ADA and American College of Cardiology discussed the use of apolipoprotein B (apo B) in patients with diabetes in a 2008 consensus panel.56

- For patients who are high risk for CAD and diabetes, in whom the LDL cholesterol goal would be <70 mg/dL, apo B should be measured. A target level is <80 mg/dL.

- For patients on statins with an LDL goal of <100 mg/dL, the target for apo B should be <90 mg/dL.

- For patients who are high risk for CAD and diabetes, in whom the LDL cholesterol goal would be <70 mg/dL, apo B should be measured. A target level is <80 mg/dL.

Smoking Cessation

- Studies of patients with diabetes have shown a much higher risk of CVD and premature death in smokers.

- Smoking results in earlier development of microvascular complications.

- Physicians should routinely assess tobacco use and encourage cessation (Chapter 45).

Screening for Cardiovascular Disease

- Silent ischemia and sudden death are more common in patients with diabetes and have prompted attempts to identify those at risk for CV events. Using a risk factor–based approach may fail to identify patients with silent ischemia.57

- Screening for asymptomatic CAD in patients with T2DM does not affect cardiac event rates or outcomes and is not recommended.58 Intensive medical therapy is equivalent to revascularization in diabetic patients.59

- Currently, the recommendation is to assess cardiovascular risk factors annually in all diabetic patients and to treat accordingly. The pertinent risk factors are as follows: dyslipidemia, HTN, smoking, family history of premature coronary disease, and presence of micro- or macroalbuminuria.

Nephropathy

- Diabetic nephropathy is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

- Microalbuminuria, defined as albuminuria in the range of 30 to 299 mg/24 hours, is the earliest stage of diabetic nephropathy in both T1DM and T2DM.

- Microalbuminuria may be CVD risk factor in addition to a renal risk factor.

- Patients with proteinuria (>300 mg of albumin/day) have a more rapid decline of kidney function than those with microalbuminuria or no albumin in their urine.

- Progressive kidney disease due to diabetes can occur in the absence of proteinuria.

- Microalbuminuria may be CVD risk factor in addition to a renal risk factor.

- Intensive glycemic control can delay the onset of microalbuminuria as well as the progression from microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria.60

- Treatment of blood pressure with an ACE inhibitor or ARB can reduce the progression of nephropathy.61,62

- Patients with progressive nephropathy despite optimal glycemic and blood pressure control and therapy with ACE inhibitor and/or ARBs should be referred for further evaluation by a nephrologist and should consider dietary protein restriction.

- The preferred method for screening for microalbuminuria is a random spot collection of urine with a calculation of the albumin:creatinine ratio.

- Two out of three measurements within 3 to 6 months should be elevated prior to diagnosis of albuminuria.

- Exercise, infection, fever, heart failure, hyperglycemia, and HTN may precipitate urinary albumin excretion over baseline values.

- Two out of three measurements within 3 to 6 months should be elevated prior to diagnosis of albuminuria.

- Serum creatinine should be measured at least yearly in patients with diabetes, regardless of the degree of urine albumin excretion. Creatinine should be used to estimate glomerular filtrations rate and to determine the stage of chronic kidney disease.

Diabetic Retinopathy

- The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy correlates with the duration of diabetes and the level of glycemic control.63

- Diabetic retinopathy is the most common cause of blindness in middle-aged adults. Other eye disorders, such as glaucoma and cataracts, also occur at an earlier age and more frequently in diabetic patients.

- Intensive glycemic control has been shown to prevent or delay the progression of diabetic retinopathy.64

- Diabetic retinopathy is completely asymptomatic; therefore, regular dilated eye examinations are recommended to identify progressive disease that will benefit from intervention before vision is lost.63

- Retinopathy is estimated to take at least 5 years to develop after the onset of hyperglycemia.63

- Patients with T1DM should have an initial comprehensive, dilated eye examination within 5 years after the onset of diabetes.

- Patients with T2DM should have an initial comprehensive, dilated eye examination soon after diagnosis.

- Patients with T1DM should have an initial comprehensive, dilated eye examination within 5 years after the onset of diabetes.

- Subsequent examinations for both T1DM and T2DM patients are repeated annually if there is no documented retinopathy. Examinations should occur more frequently if retinopathy is progressing or to determine effectiveness of treatment.

Neuropathy

Neurologic manifestations of diabetes include symmetric polyneuropathy, mononeuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, and motor neuropathy. The most prevalent are chronic sensorimotor diabetic polyneuropathy (DPN) and autonomic neuropathy.65

Peripheral Neuropathy

- Diabetic patients should be screened annually for DPN by measuring ankle reflexes, pinprick sensation, vibration perception (using a 128-Hz tuning fork), and checking for protective sensation with a 10-g monofilament test at the distal plantar aspect of both great toes and metatarsal joints.

- Loss of monofilament perception and reduced vibration perception can predict the development of foot ulcers.65

- The primary treatment of diabetic neuropathy is optimal glycemic control.

- Patients with painful DPN may benefit from pharmacologic treatment of their symptoms with tricyclic drugs or anticonvulsants.

Autonomic Neuropathy

- A careful history and physical examination are the most helpful tools in the diagnosis of autonomic neuropathy.

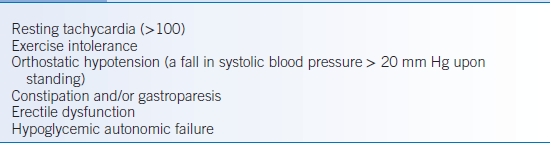

- Common clinical manifestations of autonomic neuropathy are presented in Table 20-3.

- Gastroparesis should be suspected in individuals with erratic glucose control or with upper gastrointestinal symptoms without other identified cause. The treatment of gastroparesis symptoms may improve with dietary changes and prokinetic agents.

- Treatments for erectile dysfunction often involves phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. More invasive therapies, such as intracorporeal or intraurethral prostaglandins, vacuum devices, or penile prostheses, are often required and should be comanaged with a professional specializing in erectile dysfunction.

TABLE 20-3 Clinical Manifestations of Diabetic Autonomic Neuropathy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree