Dendritic Cell Neoplasms

Histiocytes have two broad functions: antigen processing and antigen presentation. In Chapter 77, the focus was on neoplasms derived from antigen-processing cells; that is, phagocytic histiocytes/macrophages. In this chapter, neoplasms derived from antigen-presenting cells are reviewed. These include neoplasms derived from follicular dendritic cells, interdigitating dendritic cells, and Langerhans cells.

The criteria used to distinguish the various neoplastic histiocytic disorders are likely (and need) to evolve as our understanding of histiocyte and accessory cell biology improves. The current criteria in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification may lead to the impression that these entities can always be reliably distinguished. However, a degree of histologic and immunophenotypic overlap exists, and the immunophenotype of normal histiocytes also exhibits a degree of plasticity. In other words, their immunophenotypic profile depends, in part, on the microenvironment and their exposure to chemokines and other agents. It is also possible that histiocytic neoplasms may arise from a pluripotent stem cell. As a result, the cells may acquire antigens during neoplastic transformation that are not expressed by their presumed normal counterparts.

Follicular Dendritic Cell Sarcoma

Definition

Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma is a proliferation of neoplastic spindled to ovoid cells with immunophenotypic features similar to non-neoplastic follicular dendritic cells (1). In the WHO classification, the designation sarcoma/tumour is used “because of the variable cytologic grade and indeterminate clinical behavior in many cases” (1). However, as a substantial subset of these neoplasms do show malignant behavior, particularly with long clinical follow-up (2,3), in our opinion the designation of sarcoma is both simpler and accurate.

Synonyms

Dendritic reticulum cell sarcoma; follicular dendritic cell sarcoma/tumor (WHO).

Pathogenesis and Epidemiology

Follicular dendritic cell sarcomas are presumed to arise from benign follicular dendritic cells (FDCs). FDCs are thought to be most likely derived from local stroma and therefore are of mesenchymal origin, rather than being of hematopoietic origin. FDCs do not migrate and are located within lymphoid follicles where they form a stable network. FDCs are most numerous within the light zone of the germinal center, but they are also present in the dark zone of the germinal center and the mantle zone (4,5). Not all FDCs are mature; they acquire many FDC-associated antigens in a sequential manner, and desmosomes are most developed in the germinal center light zone (5,6). Maturation of FDCs is transient and reversible and requires continuous exposure to cytokines within the lymph (7).

In routinely stained tissue sections, a subset of FDCs can be recognized by their binucleated and squared-off nuclei within germinal centers. However, electron microscopy or immunohistochemistry is needed to appreciate the full magnitude of normal FDCs within a germinal center or throughout the lymph node. FDCs function physiologically by trapping and storing antigen–antibody complexes passing through the germinal center, possibly by expression of complement receptors, and then presenting these complexes to B-cells and regulating the costimulatory interactions that take place within the germinal center. Normal follicle formation and B-cell activation cannot occur without FDCs (4,5).

FDC sarcoma was initially described by Monda and colleagues in 1986 (8). Its pathogenesis remains unknown, but Castleman disease, hyaline vascular variant, appears to be a precursor lesion in a subset of patients (1,3,9,10). The small number of cases reported precludes definitive statements regarding epidemiology. In 1998, Fonseca and colleagues (11) reviewed the literature and identified 51 patients with FDC sarcoma. The median age was 41 years with a range from 17 to 76 years. In three more recent clinicopathologic studies totaling 39 patients, the median age ranged from 49.6 to 55 years (2,3,12), and the age range has been expanded from 14 to 90 years (3,12). Men and women are affected equally. Race has not been systematically specified in most studies of FDC sarcoma.

Clinical Findings

Most patients with FDC sarcoma present with a painless, slowly enlarging mass, but are otherwise asymptomatic (1,2,3,9,11). Approximately 10% of patients present with fever or weight loss (2,11). Intraabdominal tumors may be associated with pain (9). Lymph nodes are involved frequently, with the cervical region being most common, but supraclavicular, axillary, mesenteric, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes can be involved. Inguinal lymphadenopathy is rare. In approximately one-third of patients, FDC sarcoma involves extranodal sites including the oral cavity, tonsil, palate, nasopharynx, breast, pleura, gastrointestinal tract, liver, pancreas, spleen, soft tissue, pelvis, and peritoneum (1,2,3,11).

The clinical course of affected patients is variable, but with long clinical follow-up a substantial number of patients develop local recurrence. A smaller subset of patients, including most of those in whom disease recurs, develop distant metastases (1,2,3,9,11,12). The most common sites of metastases are the lung, liver, pancreas, and lymph nodes (1,9). Metastases to bone marrow have been reported rarely (13). The best treatment strategy has not been established for patients with FDC sarcoma (11). The longest disease-free survival intervals occur in patients treated with a combination of surgery, radiation

therapy, and chemotherapy (2). Chemotherapy regimens designed for lymphoma have activity against FDC sarcoma, but remissions are not durable (2,11). FDC sarcomas located within the abdomen were associated with a poorer survival in one study (9), but this was not confirmed in a more recent study (3).

therapy, and chemotherapy (2). Chemotherapy regimens designed for lymphoma have activity against FDC sarcoma, but remissions are not durable (2,11). FDC sarcomas located within the abdomen were associated with a poorer survival in one study (9), but this was not confirmed in a more recent study (3).

Gross and Histologic Findings

Follicular dendritic cell sarcomas range from 1 to 20 cm in size, with a median maximum dimension of 5 cm (1). The neoplasms are typically well-circumscribed masses, and the cut surface is gray and usually solid (1,9). Necrosis can be seen, most often in large tumors (1).

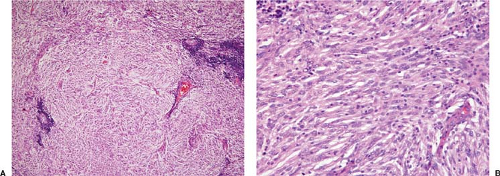

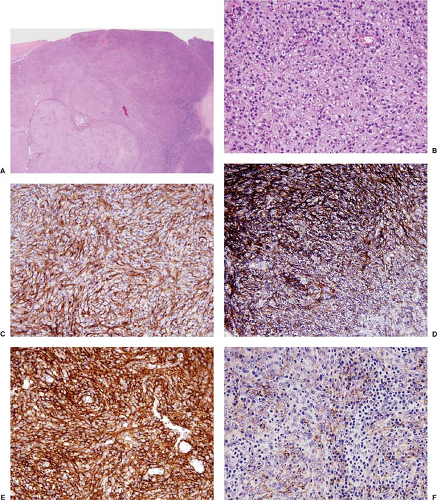

Histologically, normal tissue architecture is partially or completely effaced by a neoplasm composed of oval to spindle-shaped cells that can be arranged in various patterns including sheets, fascicles, concentric whorls, storiform, trabecular, or nodular/follicle-like (1,2,3,8,9,12,14) (Figs. 78.1 and 78.2). More than one growth pattern is the rule. In some cases, pseudovascular spaces, pseudopapillae, perivascular spaces, cystic formation, or myxoid change can be present. The neoplasm can be associated with broad bands of sclerosis that, at low-power magnification, resemble nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma. In partially involved specimens, the neoplasm is located in the cortex and often has an interfollicular pattern. In lymph nodes, there is usually a sharp border between the neoplasm and residual lymph node tissue. The margin is usually of pushing type. Characteristically, numerous small lymphocytes are interspersed between the tumor cells and form cuffs around blood vessels (Fig. 78.1A).

In many cases, the neoplastic cells have a moderate amount of pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and poorly defined cell outlines, imparting a syncytial appearance. In other cases, the neoplastic cells are more ovoid or have an epithelioid appearance (Fig. 78.2). The neoplastic cells have oval or elongated nuclei with clear or granular chromatin. Nucleoli are usually small, but they can be large and eosinophilic in a subset of cells (1,2,3,9,12,14) (Fig. 78.2). Multinucleated giant cells are present in a subset of cases. Cytologic atypia and mitotic activity are highly variable from case to case. In most cases, cytologic atypia is mild and mitoses are not frequent. Necrosis is uncommon and, if present, not extensive.

Some studies have correlated gross and histologic findings with poorer prognosis. These adverse findings include large tumor size, intraabdominal location, presence of coagulative necrosis, high mitotic activity, and cytologic atypia (2,9). In the study by Chan et al. (9), the cutoff for large tumor size was larger than 6 cm. However, histologic findings were not correlated with subsequent behavior in the study by Grogg and colleagues (3). When FDC sarcomas recur locally or disseminate, the neoplasm often shows histologic evidence of progression. This progression is manifested by increased cytologic atypia and higher mitotic activity, and necrosis is more likely to be present (2,8).

Electron Microscopy

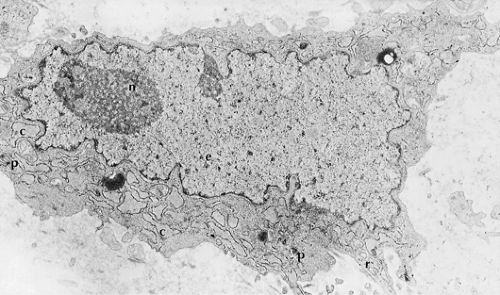

The most characteristic feature of the cells of FDC sarcoma is the presence of long, villous, interwoven cytoplasmic processes that are connected via desmosomes (1,3,8,9,12,14). The cell cytoplasm contains few organelles, including scattered ribosomes, poorly developed rough endoplasmic reticulum, short profiles of smooth endoplasmic reticulum, scattered mitochondria, and scant lysosomes. Weibel-Palade bodies, features of myofibroblasts (dense bodies, basal lamina) or fibroblasts (abundant collagen), pinocytotic vesicles, tonofilaments, intracytoplasmic lumina, dense core secretory granules, and Birbeck granules are absent. The cell nuclei are plump and ovoid with peripherally marginated chromatin and single nucleoli that are usually small, but can be large in a subset of cells (Fig. 78.3).

Cytochemistry and Histochemistry

Immunohistochemistry

FDC sarcomas express a number of antigens that can be assessed using fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections (1,2,3,8,9,10,11,12) (Fig. 78.2C–F). Most of these antigens are not specific for FDC sarcoma. Antibodies reactive with clusterin, fascin, and epidermal growth factor receptor (Fig. 78.2C) are most sensitive, highlighting over 90% of cases (2,3,15). Follicular dendritic cell sarcomas also commonly express the FDC-associated

antigens CD21 (C3d receptor), CD23, and CD35 (C3b receptor) (Fig. 78.2D,E). Other monoclonal antibodies that react with FDC-associated antigens work better in frozen rather than in routinely processed tissue; these include R4/23, Ki-M4, Ki-M4p, and Ki-FDC1p (11). Most cases of FDC sarcoma are positive for low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor, CNA.42, epithelial membrane antigen (Fig. 78.2F), vimentin, desmoplakin, and HLA-DR (1,16,17). CD68 and S100 protein are variably positive in FDC sarcomas; often they are focal or weakly expressed (2,12). CD45 (LCA) is positive in approximately 20% of cases (11). CD20 was positive in a small subset of the neoplastic cells in three of 13 (23%) cases reported

by Pileri and colleagues (12). FDC sarcomas are negative for T-cell antigens, B-cell antigens (except CD20 occasionally), CD1a, CD30, CD34, myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, cytokeratins, HMB-45, actin, desmin, and vascular markers. Ki-67 immunostaining reflects the variable mitotic rate in these tumors. In the study by Pileri et al. (12), the Ki-67 rate ranged from 1% to 25%. Epstein-Barr virus small-encoded RNA (EBER) is rarely detected in FDC sarcoma (9,12), with the exception of lesions reported as FDC sarcoma in the liver that simulate inflammatory pseudotumor (18). The best classification for these lesions in the liver is uncertain, and they may not be true FDC sarcoma.

antigens CD21 (C3d receptor), CD23, and CD35 (C3b receptor) (Fig. 78.2D,E). Other monoclonal antibodies that react with FDC-associated antigens work better in frozen rather than in routinely processed tissue; these include R4/23, Ki-M4, Ki-M4p, and Ki-FDC1p (11). Most cases of FDC sarcoma are positive for low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor, CNA.42, epithelial membrane antigen (Fig. 78.2F), vimentin, desmoplakin, and HLA-DR (1,16,17). CD68 and S100 protein are variably positive in FDC sarcomas; often they are focal or weakly expressed (2,12). CD45 (LCA) is positive in approximately 20% of cases (11). CD20 was positive in a small subset of the neoplastic cells in three of 13 (23%) cases reported

by Pileri and colleagues (12). FDC sarcomas are negative for T-cell antigens, B-cell antigens (except CD20 occasionally), CD1a, CD30, CD34, myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, cytokeratins, HMB-45, actin, desmin, and vascular markers. Ki-67 immunostaining reflects the variable mitotic rate in these tumors. In the study by Pileri et al. (12), the Ki-67 rate ranged from 1% to 25%. Epstein-Barr virus small-encoded RNA (EBER) is rarely detected in FDC sarcoma (9,12), with the exception of lesions reported as FDC sarcoma in the liver that simulate inflammatory pseudotumor (18). The best classification for these lesions in the liver is uncertain, and they may not be true FDC sarcoma.

The small lymphocytes intermixed within FDC sarcoma may be predominantly B cells (CD20+), T cells (CD3+), or an equal mixture of both lineages. The small B cells in FDC sarcomas are polyclonal and do not express CD5, but can be positive for CD23 in some cases.

Molecular Diagnosis

FDC sarcomas show no evidence of immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor gene rearrangements. The human androgen receptor gene (HUMARA) assay has been used to prove the monoclonal origin of dendritic cell tumors, including FDC sarcomas (19).

Differential Diagnosis

The lesions of inflammatory pseudotumor are characterized by spindled cells, small vessels in the lymph node capsule extending along trabeculae, and a variable mixture of inflammatory cells. In contrast with FDC sarcoma, the spindle cells of inflammatory pseudotumor have less of a syncytial appearance and no cytologic atypia. These spindle cells may be associated with many plasma cells. The spindle cells of inflammatory pseudotumor are negative for FDC-associated antigens (e.g., clusterin, CD21, CD23, etc.).

In ectopic meningioma, the syncytial appearance of the spindle cells and positivity for EMA can mimic FDC sarcoma. Immunohistochemical stains show that meningiomas lack FDC-associated antigens.

Ectopic thymoma can closely simulate FDC sarcoma histologically. Immunohistochemical analysis is often needed: The neoplastic cells of thymoma are positive for keratin, and the small lymphocytes are of immature T-cell lineage, positive for T-cell antigens and TdT.

The neoplastic cells of histiocytic sarcoma are usually less spindled than FDC sarcoma, often show more pleomorphism, and may exhibit hemophagocytosis. Immunohistochemical analysis is very helpful: Histiocytic sarcomas express histiocyte-associated antigens (e.g., CD68, lysozyme, etc.) and are negative for FDC-associated antigens. Electron microscopy shows no evidence of desmosomes.

Interdigitating dendritic cell (IDC) sarcoma histologically, the neoplastic cells of IDC sarcoma tend to be less elongated and plumper than the cells of FDC sarcoma, but in some cases of IDC sarcoma the cells can be very spindled. Electron microscopy of IDC sarcoma does not show well-formed desmosomes, although cellular junctions have been reported in some cases (12). Immunohistochemistry is helpful: S100 positivity is strong, and CD68 and LCA (CD45) can be positive in IDC sarcoma. Unlike FDC sarcoma, IDC sarcoma is negative for clusterin and FDC-associated antigens. Fascin is not helpful in this differential diagnosis.

Large-cell lymphomas of B- or T-cell lineage are usually not spindled, unlike FDC sarcoma. Immunophenotyping showing expression of B- or T-cell antigens easily makes this distinction. Molecular studies showing the presence of

immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor gene rearrangements is helpful if needed.

Rare cases of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) can be very spindled (sarcomatoid variant), and ALCLs often express clusterin (3,20). Usually, cases of ALCL have some areas (often perivascular) where hallmark cells can be identified. Anaplastic large cell lymphomas are positive for CD30 and ALK, express T-cell antigens and carry T-cell receptor gene rearrangements in most cases, and are negative for most FDC-associated antigens.

In lymphocyte-depleted classical Hodgkin lymphoma (LDHL), a mixture of inflammatory cells is usually present in the background, and Reed-Sternberg and Hodgkin cells express CD15 and CD30.

Carcinomas. The intermingled small lymphocytes and cohesive appearance of the neoplastic cells of FDC sarcoma can simulate lymphoepithelioma-like or spindle cell carcinoma. Plasma cells or eosinophils are often present in lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. Immunohistochemical demonstration of keratin expression distinguishes these lesions from FDC sarcoma.

The neoplastic cells of malignant melanoma are usually much less spindled than FDC sarcoma and may contain melanin pigment. Immunohistochemical stains showing strong S100 protein expression, associated with other melanoma-associated markers (e.g., HMB-45, etc.) distinguishes these lesions from FDC sarcoma.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumor angiosarcoma and other spindle cell sarcomas may superficially mimic FDC sarcoma. The spindled cells in these entities usually have less of a syncytial appearance, and cytologic atypia is usually much greater than in FDC sarcoma. Immunohistochemical staining is very helpful: spindle cell sarcomas do not express FDC-associated antigens.

Interdigitating Dendritic Cell Sarcoma

Definition

Interdigitating dendritic cell (IDC) sarcoma is a neoplastic proliferation of spindle to ovoid cells with immunophenotypic features similar to those of interdigitating dendritic cells (1).

Synonyms

Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma/tumor (WHO).

Pathogenesis and Epidemiology

Interdigitating dendritic cells are of hematopoietic origin, arising from CD34+ bone marrow precursors that mature and eventually take up residence in the T-cell regions of normal lymphoid tissue, including the paracortex and deep cortex of lymph nodes and tonsil, the periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths of the spleen, and the thymic medulla (21,22). IDCs also can be found in the T-cell regions of abnormal lymphoid tissue, for example, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue at extranodal sites. IDC maturation is induced by cytokine and microenvironmental influences. The principal known function of IDCs is to present antigen to T cells in a major histocompatibility antigen–restricted fashion (21,22).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree