1

Chapter Outline

| Web Toolkit available at www.ashp.org/ambulatorypractice |

Chapter Objectives

1. Define the practice of ambulatory patient care.

2. Apply the standard of practice for ambulatory care to your site.

3. Compare and contrast different practice constructs and settings.

4. Describe services provided by ambulatory care pharmacists.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, various organizations and committees have issued edicts to the profession of pharmacy: become more involved in patient care.1,2 It was under the auspices of this challenge and factors such as the aging population, reduced hospital length of stay, and emerging pay-for-performance measures, that innovative pharmacists and health systems developed ambulatory pharmacy practice.3

Transcending the practice setting, the practice of ambulatory care can be defined most simply and inclusively as providing health-related services in which patients walk to seek their care.3 This definition holds true despite the fact that ambulatory care practice, like much of health care, continues to evolve. It is interesting to note that among those who practice ambulatory care, trying to become more specific with this definition results in becoming more divisive. That is to say, you won’t have the same needs, resources, collaboration, or scope of service for a practice that is based in a medical center as in a physician’s office or a community pharmacy. So, although patient care services may appear to be similar, practice setting and organizational differences may affect your scope of service and the way in which those services are delivered.

Despite these inherent differences in various practice settings, enough commonality exists within the practice to define an ambulatory care standard of practice. According to Carter, “The most important aspect of developing an ambulatory practice is appropriate planning.”3 Thus, your new practice is a study of intelligent design based on the evolution of others’ prior practices. Ultimately, it is your knowledge of how this ambulatory care standard of practice applies to these different settings, and in particular, your setting, that will allow successful implementation and a successful practice.

| Your new practice is a study of intelligent design based on the evolution of others’ prior practices. Your knowledge of how this ambulatory care standard of practice applies to these different settings, and in particular, your setting, will allow successful implementation and a successful practice. |

Standard of Ambulatory Care Practice

Leadership, patient care, and medication management are characteristics that exist in all ambulatory settings, contributing to the framework of an applicable standard of practice.1,4–6 Realistically, however, these key factors exist in different degrees and complexity in different settings. This standard defines a practice with a solid foundation of each of these components and then further provides details of those attributes that exceed the standards or should be considered a “best practice.” The standard of practice, then, probably contains some aspects already present in your organization or site and some aspects that will need to be initiated or further developed.

Despite the fact that ambulatory care has been a practice for the last 40 years and is growing wider in acceptance largely due to increased visibility, both in practice and in the literature, strong leadership is necessary for the success of your practice. This leadership comes in the form of profession-wide, individual practice management and personal scope.

Leadership Standard

Becoming a Leader in Ambulatory Pharmacy Practice

The practice of ambulatory care will continue to develop as those involved, perhaps you, continue to develop new and innovative practices. However, what you accomplish through leadership at your local level should also have an impact on the national practice. You must share what you have accomplished and learned along the way with others in the profession, or in other words, give back to the profession. You can accomplish this through teaching, giving presentations, or contributing to publications. Each of these venues has its own strengths. For instance, publications may reach a larger audience, be permanent, and influence national guidelines. Your precepting or clinical teaching may reach a smaller audience but give a more detailed view of the infrastructure of the practice that can live on through the next generation of ambulatory care pharmacists that you train.

| Share what you have accomplished and learned along the way with others in the profession, or in other words, give back to the profession. |

You should also ensure that you and your team are actively involved in local, state, and national organizations. This “active participation” is more than organizational membership; it is involvement in projects, serving on committees, and holding offices. Your participation in this manner continues to highlight ambulatory care practice. The relationship also bears benefits to all involved in the form of learning and understanding differing points of view as well as job satisfaction.

Advocacy, however, is likely the most important need for the practice. Advocacy can be accomplished at both a practice and professional level. As you build your practice, continue to advocate for it by sharing successful metrics with the stakeholders. Do not underestimate the power of patient satisfaction. Patient’s word of mouth can be more powerful than facts and figures. Surely, if the patients are happy and you are getting results, physicians and other team members will be happy and likely refer more patients. Thus, the patients, physicians, health care team, and health systems are aware of your presence.

On a national level, the professional organizations have advocacy committees and training programs. Simple things such as giving information when asked, inviting government officials to your practice, and keeping up with health care reform issues can be very valuable.

| Find your political voice and stay informed. |

Being a Leader on Your Team

As depicted in Table 1-1, leadership and management roles and tasks are usually addressed separately. You need to consider both as you begin to build your practice.7 Although a less familiar term in the pharmacy profession compared with the medical profession, practice management is literally the way you run your business of ambulatory clinical service and the way you manage your practice. You should first develop the mission and vision of what the practice should be.8,9 As Covey states, “begin with the end in mind.”10 Developing mission and vision statements for your program or service is a good way to get started. By putting these thoughts into words, you create a powerful tool that provides a focus and guides in the creation of your service or program. The mission statement should describe the purpose of your program and why it needs to exist in a clear, concise, and informative manner. Involve all key members of your team in composing your statements so that everyone understands your program’s purpose. The vision statement defines where the program and service is going, or what it wants to achieve and accomplish at some future point and time, usually at an interval of 5–10 years. The value of the service or program should be articulated in the vision statement. (Examples of mission and vision statements can be found on the web.)![]()

Table 1-1. Leadership and Management Responsibilities7 | |

| Leadership | Management |

| Scanning | Planning |

Identify client/stakeholder needs and priorities Recognize trends, opportunities, risks Look for best practices Identify staff capacity and constraints Know yourself, your staff, your organization values, strengths, and weaknesses | Set short-term organization goals and performance objectives Develop multiyear and annual plans Allocate appropriate resources Anticipate and reduce risks |

| Focusing | Organizing |

Articulate the organization’s mission and strategy Identify critical challenges Link goals with the overall organizational strategy Determine key priorities for action Create a common picture of desired results | Ensure a structure that promotes accountability and delineates authority Ensure the systems for human resource management, finance, logistics, quality assurance, operations, information, and marketing effectively support the plan Strengthen work processes to implement the plan Align staff capacities with planned activities |

| Aligning/Mobilizing | Implementing |

Encourage congruence of mission, values, strategy, structure, systems, and daily activities Facilitate teamwork Unite key stakeholders around an inspiring vision Link goals and rewards and recognition Enlist stakeholders to commit resources | Integrate systems and coordinate work flow Balance competing demands Routinely use data to make decisions Coordinate activities with programs and sectors Adjust resources based on change |

| Inspiring | Monitoring and Evaluating |

Match deeds to words Demonstrate honesty in interactions Show trust and confidence in staff Provide staff with challenges, feedback, support Be a model of creativity, innovation, and learning | Monitor and reflect on progress of plans Provide feedback Identify needed changes |

Once your mission and vision are determined, follow by determining your goals and strategic planning. These should closely align with your program’s mission and vision. Goals are predetermined indicators for success and should be continuously and objectively measured. Those responsible for the goals should be held accountable for them. The accountability should “roll up.”11 This means that although not all of your staff may have the same goals, depending on the projects in which they are involved, you as the leader of the practice or site should be held accountable for the goals of everyone who reports to you. Chapter 7 will discuss this in more detail and proven case examples.

The team should be built with this mission/vision/goal/strategic plan in mind. Where applicable, you should incorporate peer interviewing (asking behaviorally based questions) and ranking scales (weighted, objective/subjective) to build the team. When this is done, those doing the interviewing take responsibility for the new team members. It fosters a supportive system aligned to common goals. For instance, Schneider et al. found that according to pharmacy staff, patients should (1) understand the benefits and adverse effects of their medications, (2) not experience a preventable adverse drug event, (3) receive the correct dose and medication, (4) not receive a drug to which they are known to be allergic, (5) receive medications in a timely fashion, (6) have doses individualized when necessary, and (7) receive the most effective therapy at the least cost.12 Here, the pharmacy staff basically defined their standards for patient care, and at times the specific job descriptions can be built around these expectations.

Table 1-2 describes possible components of an ambulatory care pharmacist’s job description and examples of services. Along with hiring, you must ensure fair market benefit—remuneration for associates that is fair based on what the market would bear.13 This can be done if you have a working knowledge of or responsibility for the practice budget. You can more easily advocate for your associates if you understand the productivity and financial sustainability of the practice.

Finally, you must discern what policies and procedures are necessary to make your practice run smoothly. Some of these may be in existence in other practice areas; however, some may need to be created from scratch. Policies and procedures should be standard enough to promote consistency but flexible enough to promote clinical judgment. Knowledge of stakeholders and accrediting organizations will guide you in compiling organizational policies and procedures in the areas of human resources, medication control, patient care, laboratory guidelines, and process management. Use Chapter 5 to help you with this process.

How to Be a Leader

In order to launch an ambulatory care practice, you and your team will be more successful if you personally possess practice experience and knowledge, an innovative or entrepreneurial spirit, and experience in building culture along with managing change. Of course, primary knowledge, as well as experience in a particular task, is an asset to any project. You can gain knowledge of successful practices through the literature. However, literature results alone may not satisfy your administrators; they may ask you for the corresponding positive return on investment. That said, successful business plans or organizational descriptions are very rarely published. Chapters 2 and 3 will help you in this regard. Also, in lieu of firsthand experience, networking can provide you with gains in this area. Experience derived in this manner may be more practical for you if it can be directly applied to your practice. The best way to get this kind of insight is to participate in national conferences in the area in which you practice. Please see the web page for a list of organizations, meetings, and meeting dates you may wish to consider attending.![]()

Professional chat rooms, web-based professional communities, blogs, and professional organization sites such as ASHP (American Society of Health-System Pharmacists) Connect are great avenues for asking questions and getting various different points of view from those already in practice. Many practices are organization specific, so be sure to use resources within your own organization (compliance staff, billers, etc). Combine knowledge of the possibilities with the experience in other practices to create your own knowledge base.

Because ambulatory care is a diverse practice going in multiple directions, it is imperative that you or your leader has a true entrepreneurial spirit. Creativity is a must as you start to apply the knowledge and experience gleaned from others. There is no doubt that something will need to be altered to fit, that some barrier will exist to be overcome, or that someone will need to be convinced of the relevance of building or growing the practice. The key to success in many of these discussions is to listen for understanding, consider the opinions and points of view of those involved, and create a novel, better plan that more than meets everyone’s needs.10,17 During this endeavor, a leader who exhibits a spirit of innovation can provide the spark that lights the fire in others.10,11

Finally, you must have a leader and team who are able to deal with change while maintaining a culture of service. Even if this is not a new undertaking, your practice will continue to change as new ideas and initiatives are realized. Different metrics will need to be designed to determine the success of your practice. You must have the wherewithal to work and have others work in a rapidly changing environment while still maintaining high morale.1,18 As shown in Table 1-3, communicating, empowering, and recognizing accomplishments are all ways to maintain morale.

| Table 1-3. Factors Affecting Change in an Organization18 |

| How to Successfully Advance Change |

| Establish a sense of urgency. |

| Form a coalition to lead the change. |

| Create a vision and establish strategies to achieve it. |

| Communicate the vision. |

| Empower others to act on the vision. |

| Plan for and create visible short-term accomplishments. |

| Produce more change by increased credibility. |

| Promote and institutionalize effective new behaviors. |

A practical way to ensure that people are actively engaged and not burned-out is to talk to each person at least monthly.11 Talking to your staff and using the questions in Table 1-4 keeps you in touch with the practice atmosphere and needs. If this process is done sincerely, your people will feel supported and satisfied, and this translates to quality patient care. Furthermore, transparent communication to the whole group focusing on perceived problems versus reality is a proven method to allay fears and quell the rumor mill.

Table 1-4. Questions Asked During a Rounding Session11 | |

| Question | Comment |

| What is going well today? | Always start on a positive note. |

What can be improved? | Make sure to have the associate focus on what can be improved with the department, not the associate’s performance. Build a better process, not a better person. |

Do you have the tools | Allows you to meet needs before they become critical. It is important to follow through by either getting what is needed or explaining why you can’t. If not, it undermines your sincerity. |

Is there anyone I should | Thank you notes should be written to the specified individuals. This recognizes accomplishments and rewards appropriate behaviors. It also fosters good relationship developing between the person recognized and the person who recommended the recognition. |

Beyond the Leadership Standard

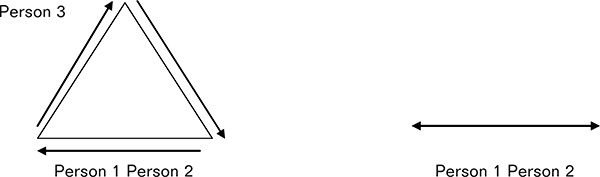

Everyone within your organization has a professional duty to communicate transparently with each other. Transparency, in this sense, means no hidden agendas, no grudges, no passive aggression, and clear communication and clarification of expectations. Likewise, you should disallow triangulation. As depicted in Figure 1-1, triangulation is the process of bringing unnecessary people into disagreement or discussion—fostering office politics. Those involved in the problem or situation must respect each other enough to confront the issue at hand, rather than involve a third party. These steps are sometimes easier said than done, and likely they become more difficult the larger the staff and the more separated, geographically, they are.

| Everyone within your organization has a professional duty to communicate transparently with each other. |

Figure 1-1. Example of Triangulation

In this triangulation, person 1 and person 2 have a conflict, and person 3 is brought into the program unnecessarily. The line on the right represents appropriate communication between two professionals.

You should encourage the development of leaders from within the practice, or site leaders from within the practice can become champions of a program or initiative, making it run smoothly.19,20 Because these leaders are more on the “front lines,” they can assist in troubleshooting or changing direction before calamity occurs. Many times you can simply foster leadership by soliciting and listening to opinions of those within the team. Another way in which to engage dormant leaders is to find and incorporate their strengths or passions into projects you would have them lead. In describing the transitions in pharmacy practice in 2000, Nimmo and Holland stated, “. . . much of what pharmacists will do or not do during a workday is driven by their professional values—by what is important and what obligations are to be met—rather than by some carefully defined list of tasks.”21

There are no satisfied patients without satisfied clinicians. Clinicians do gain satisfaction from purposeful work.13 However, this purposeful work must be competitively remunerated. The concept that “everyone is your competition” can also be applied to salary adjustments within the organization. When arranging the pay scale for pharmacists in your organization, is it based on like businesses or where the competition lies? Where does the competition lie? The answer is the entire profession: a pharmacist with a license could interview for any pharmacist position in any type of practice. This being the case, you must expand analysis of salary for all positions based on the entire practice of pharmacy to maintain your competitive edge.

Finally, it is imperative for you to share your systems and your “secrets” freely for the betterment of the profession, even at the local level. This could be accomplished with publications, presentations, blogs, professional electronic communities, and Twitter, to name a few. Do not let the fear of competition keep you from open and transparent communication outside of your organization. Rather, when you have done something unique or novel that positively impacts the profession or patients, tell or show others in the profession. Duplication of such a system or practice model will better establish it within the health care system and impact more patient lives. Moreover, mutual support with amicable competition results in further innovations and growth.

Patient Care Standards

Patient Care

Patient care is likely the most recognizable and defining characteristic of an ambulatory practice, you likely gravitate toward a practice in ambulatory care if you enjoy forming long-lasting relationships with patients while using your clinical skills to help them manage their various disease states and medication regimen. It is possible that this is the only part of the standard that requires implementation, as the other aspects may already exist within your system.

Patient care has been called many things over the years as pharmacy transitioned from a product to a patient-based profession: cognitive services, disease state management, pharmaceutical care, pharmacotherapy, and medication therapy management (MTM) services. Even though it existed under different names, the basic premise of pharmacy has not changed: care involves the process through which a pharmacist cooperates with a patient and other professionals in designing, implementing, and monitoring a therapeutic plan that will manage a patient’s disease, eliminate or reduce a patient’s symptoms, arrest or slow disease progression, or prevent a disease.14 Moreover, these tenets apply whether your practice focuses on an individual patient or an entire patient population and whether your practice is part of a collaborative interdisciplinary team effort or a more independent venture. You should ensure that those charged with the care of another human being have appropriate training and an appropriate knowledge base, should be able to apply the knowledge base to individual patients, and exhibit empathy and compassion during patient care.

| Regardless of your type of practice or practice focus, ensure that your patient care staff have appropriately trained clinically and have the ability to exhibit empathy and compassion to those in their care. |

Training

Patients will assume you and your staff are appropriately trained for the position you hold simply because you hold the position.11 It is your duty to make sure that the people on your team or those you invite to join your team are appropriately trained to take care of these patients. Since ambulatory patient care requires training and skill sets beyond that of initial pharmacy licensure, postgraduate training, pharmacy practice and specialty residency programs, or comparable experience should be considered the standard for practice.22,23

When considering a postgraduate-trained pharmacist, you may want to set an individual practice or organizational standard for how much time a practitioner spent in an ambulatory care setting, as residency programs differ. A residency program will assure you that your pharmacist can take care of a diverse patient population. No doubt both the new resident-trained clinicians and the established clinicians will feel slightly uncomfortable, depending on the level of experience they currently have when venturing into new practice situations; it is your responsibility to ensure that you move them from consciously incompetent to consciously competent as depicted in Table 1-5. It is imperative that your pharmacist should be trained appropriately for the position or patient populations with whom you would entrust them. Even though the service you offer may be very specific—anticoagulation, congestive heart failure, or diabetes management—your pharmacist will come into contact with patients with many other disease states in the context of your service. If it is a new service or program, you should ensure that a training plan is established, monitored, and completed before patient care ensues. Determining the best method to ensure competency of your staff is further discussed in Chapter 7.

| It is imperative that your pharmacist should be trained appropriately for the position or patient populations with whom you would entrust them. |

Table 1-5. Stages of Competence24 | ||

| Competencea | Description | How to Move to the Next Stage |

| Unconscious incompetence | Don’t know what you don’t know or happily ignorant | Listen to people who point out blind spots |

| Conscious incompetence | Know what you don’t know or cognitive dissonance | Study and practice |

| Conscious competence | Know | You have experience |

| Unconscious competence | Don’t know you know | You are an expert |

aStages of competence through which you will progress when asked to take on a new task or learn a new topic. | ||

Application

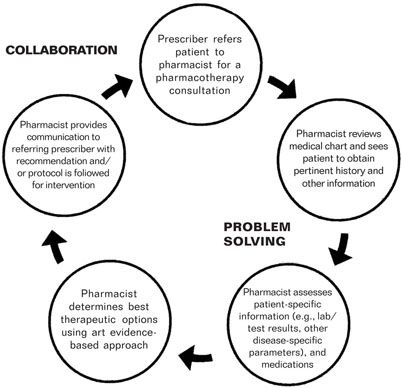

Drawing from several references and our own ambulatory care practice experiences, we propose Table 1-6 as the minimum standard of care for your ambulatory practice.4–6,14,26 Patient care should be both prospective and comprehensive in nature (Figure 1-2).5 Even if you have been consulted for a very specific reason, you have a duty to evaluate the whole patient, determining which things you can manage and which things need to be recommendations back to the provider based on the referral. Before you sit down in the room with the patient, you should independently gather the patient’s medical information for pertinent past medical history, allergies, medications, and laboratory data.4,6,7,14,26 Goals of therapy, including surrogate end points and patient outcomes, should be determined.

| Goals of therapy, including surrogate end points and patient outcomes, should be determined. |

Table 1-6. Seven Standards of Ambulatory Patient Care4–6,14,25 Minimum Standards of Care for Your Ambulatory Care Practicea | |

| 1. | Interviewing patients and caregivers to gather pertinent information for patient care |

| 2. | Assessing the legal and clinical appropriateness of medication regimen |

| 3. | Identifying, resolving, and preventing medication-related problems |

| 4. | Participating in pharmacotherapy decision making |

| 5. | Educating patients and caregivers on disease, pharmacotherapy, adherence, and preventative health |

| 6. | Monitoring the medication effects and patient’s health outcomes |

| 7. | Maintaining medication profiles and other documentations |

a For a more detailed list of standards, refer to the different domains outlined in the Board of Pharmacy Specialties’ Ambulatory Care Pharmacy Specialty Certification Examination document that can be found at http://www.bpsweb.org/resources/content.cfm.

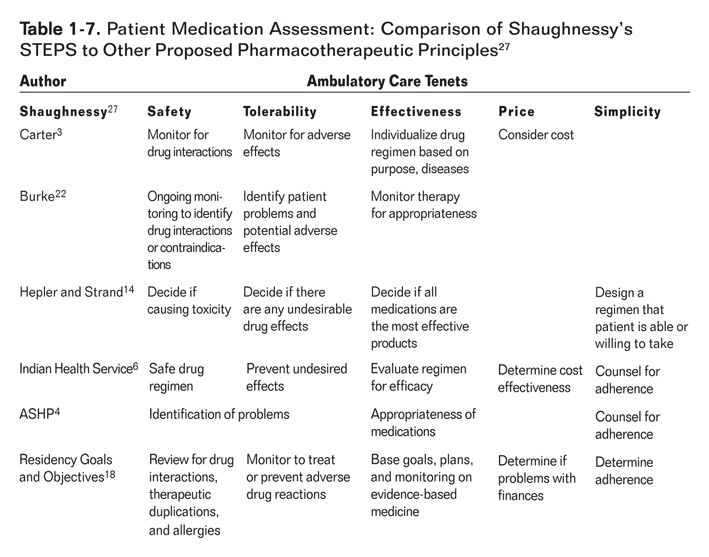

Upon reviewing this information, you should assess the current plan for appropriateness. A useful exercise is to have clinicians determine how they systematically approach patient care. If they can discover and duplicate this approach, it is less likely that issues affecting patient care will be missed. One question serves as the basis for this evaluation: are the medications appropriate based on patient-specific factors and available evidence? Applying Allen Shaughnessy’s method of evaluating a specific agent—safety, tolerability, effectiveness, price, and simplicity (STEPS)— to multiple different agents for an individual patient incorporates the different aspects of many proposed standards of patient care.27 (See Table 1-7.)

Figure 1-2. Prescriber-Pharmacotherapy Specialist Relationship

(Reprinted with permission from Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Scope of contemporary pharmacy practice: roles, responsibilities, and functions of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. Washington, DC: Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy; 2009.)

- Is the entire medication regimen safe for the patient? You must make sure that the regimen has no potential for allergic reactions, has no therapeutic duplications, and has no potential for drug-drug, drug-disease, or drug-food interactions.

- Is the patient tolerating the regimen? You must ensure that the patient is not exhibiting signs or symptoms of suffering from untoward effects from the medication.

- Is the regimen effective? Looking at patient-specific criteria, you must evaluate if the current regimen is evidence based for the diseases that the patient has. Also, you must decide if the current regimen is optimized compared to the evidence-based goals of therapy.

- Is the patient able to afford the price? Cost should always be a consideration in the choice of a regimen. Many times your patient may be ashamed to discuss financial difficulties and end up not adhering to the regimen prescribed. It is your responsibility to ensure a cost-effective regimen is provided.

- Is the regimen simple for the patient to take? Does the patient understand why and how he or she is to take the medication regimen? You must assess whether or not you think the patient could adhere to the regimen based on frequency of dosing of the different agents and plan to substitute alternatives as necessary. It is also important to form an assessment of how knowledgeable the patient may be regarding the medication therapy regimen.

On review of the patient’s medication regimen, response to therapy, and medical history, you can develop a tentative pharmacotherapeutic plan going forward. Many times this may be an “if/then” scenario, not having one set plan but several courses of action plotted out. This plan should address issues unearthed during review of the patient’s medical record, including modifications of the current drug regimen, suggestions for lifestyle modification, a follow-up monitoring plan, a preventative action, and a patient education plan.

Once this plan is developed, the patient interview and evaluation can take place. Initially, you should ask patients what their primary concerns are, what their under standing of the visit is, and what they hope to accomplish during the visit. This quickly sets the tone and expectations of the visit and allows the patient to start talking. You should then question the patient about symptoms of the ongoing disease processes as well as medication effects. Vital signs and laboratory data necessary for the visit should be obtained at this time. Clarification or reconciliation of the medication regimen, including differences in how the medication is prescribed versus how the patient takes or administers it, allows for a more defined pharmacotherapy plan. During the course of this conversation you can establish common goals and plans of action with the patient.

| Combining your initial review of the patient’s medical history with the patient interview allows you to implement or adjust your plan going forward. |

This encounter should be documented in the patient’s medical record.1–6,7,14,22,26 Chapter 6 will further discuss optimal documentation.

Continuity of Care

You should ensure that care is collaborative, with steps in place to maintain continuity, in particular around medications, among all clinicians caring for a particular patient. Often the required collaboration will be defined by the collaborative drug therapy management agreement and the referral. However, collaboration goes beyond your team and may include a diverse group of providers such as the dispensing pharmacist, a hospitalist, a home nurse, etc. Not only should the ambulatory pharmacists take responsibility for medication reconciliation around all transitions of care, but it is also imperative that you have a process to communicate your patient-specific actions and plans to all providers that touch your patient so that the patient’s specific plan of care is truly one coordinated plan.

Continuity assures that other appropriate laboratory and other tests are completed or that other diseases are being addressed without duplication. Most importantly, continuity measures ensure that other providers are aware of the entire patient’s clinical information so that decision making at each point of care is optimal. Collaboration allows a complete management of the whole patient as a team. You have much to offer to the team when it comes to drug, dosing, interaction, cost information, adherence strategies, and beyond. Care should be taken to support the team when opportunities arise: praise efforts of other providers publicly, and question or criticize privately. This builds the patient’s confidence in the whole team. Ultimately these communications should be included in the patient’s medical record.

It is also important to note that once you have implemented a pharmacist-managed program, your utmost commitment to continued service should be exercised and that it should not be a sporadic service delivered only when time, resources, and staffing are plenty. It has been documented that quality of outcomes decrease when patients are discharged from a pharmacist-managed clinic or when pharmacist-delivered interventions are removed and patients have to return to the usual care. For example, even after stabilization of warfarin therapy, transition of patients from a pharmacist-managed anti-coagulation clinic back to physician-managed anticoagulation care resulted in significant decrease in International Normalized Ratio (INR) control, increased medical care related to anticoagulation, and decreased patient satisfaction.28 When a comprehensive pharmacy care program was removed from community-dwelling older patients using polypharmacy after 6 months, medication adherence returned to near-baseline levels, whereas patients who stayed with the comprehensive pharmacy care program maintained their adherence consistently above 95%, resulting in further improved blood pressure control.29 Moreover, providing inconsistent care will compromise your credibility within the organization and among your health care team and patients.

| It is also important to note that once you have implemented a pharmacist-managed program, your utmost commitment to continued service should be exercised and that it should not be a sporadic service delivered only when time, resources, and staffing are plenty. |

Patient Education

It is widely known that pharmacists are patient educators. The disease and medication knowledge you possess can be invaluable to patients and their caregivers when delivered in an effective manner. The ambulatory care setting is especially suited for educational sessions with minimal pressure of acute illness or emergent procedures. Specifically, patients being prescribed a medication for a new diagnosis, a regimen change being performed for better control of a condition, or strategies being applied to improve adherence or to alleviate a drug-related problem are golden opportunities for you to provide essential education. Patients’ understanding of antibiotic resistance and appropriate antibiotic use improved following a pharmacist-initiated educational intervention in an urgent care clinic, where patients reported satisfaction with the intervention.30 Development of a constructive and relevant relationship between you and the patient must be cultivated. Knowing the patient’s condition and preferences facilitates patient encounters for education. Whenever possible, your communication strategy should be tailored to the patient’s background, cultural preferences, and health literacy.31 Pharmacists’ education (primary intervention among other strategies) in a drug optimization clinic significantly improved HIV-infected patients’ CD4+ lymphocyte counts, viral loads, and drug-related toxicities.32 Regular use of available tools to promote health communication between patients and providers should be an integrated part of your educational session.33

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree