Dealing With Patient Adherence Issues

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• INTRODUCTION

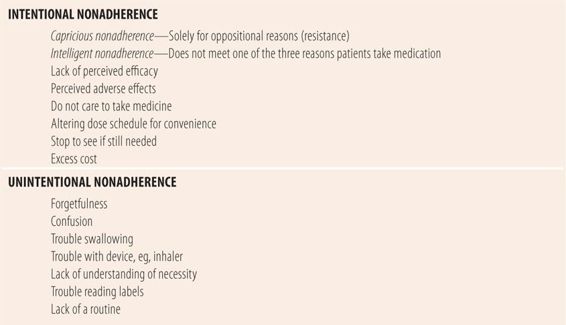

Medication nonadherence is a major public health problem. Nearly half of the 187 million people who take medications in the U.S. do not take them as prescribed. Poor medication adherence costs over $100 million annually. Patients with poor adherence to diabetes medication cost the health care system twice as much as patients with high adherence. While adherence to medication is a problem, adherence to diet and exercise, and other therapeutic modalities is even less than for medications. There is great confusion about what medication nonadherence is. Are you nonadherent if you miss or are late for any dose? Or are you considered adherent if you take 80% or more of your medication? Every study or review article uses different definitions. There is also confusing terminology. Compliance was the original term, but was considered to be politically incorrect by some because it implied following the providers’ orders. Adherence came next because it is more politically correct than compliance and is the current “in” term in the United States. Persistence refers to how many pills are picked up from the pharmacy and is more of an economically focused term. Finally, experts in the United Kingdom thought that adherence was as bad as compliance and used concordance to better represent that the patient was in partnership with their provider and worked closely together to optimize patient outcomes. Finally, we have classified medication adherence into two categories: intentional and nonintentional (Table 5.1). This classification has some utility because it does generally relate to potential interventions to improve medication adherence.

| TABLE 5.1 | Types of Nonadherence |

• PROVIDER MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT MEDICATION ADHERENCE

There are numerous misconceptions about medication adherence among health care providers. The major misconception is that they “manage” a patient’s chronic disease. In reality, the only time a health care provider manages a chronic disease is the 15 to 30 minutes during periodic follow-up visits. The remainder of the time the patient manages their chronic disease. One expert said that providers need to recognize “whose disease is it anyway?” A corollary problem with providers is the common belief that they can motivate patients to adhere with their therapeutic regimen. Unfortunately, behavioral sciences have shown that all motivation is self-motivation and that cheerleading style approaches have limited utility and may lead to decreasing rates of adherence. Similarly, some feel that if they clearly explain the risk of suboptimal adherence, patients will automatically be motivated to take their medication as prescribed. Some providers tell patients that if they do not take all their medications they will have a stroke or heart attack in hopes of motivating them toward better adherence. This threatening, chastising approach, like the cheerleader approach, has limited utility and may lead to results that are opposite of what they are trying to accomplish. Because of this class of misconceptions, some providers perceive patient’s suboptimal adherence as a personal rejection of their advice and become angry with patients who do not perfectly control their chronic disease.

Many providers are also unaware of how much medication adherence is required to cure acute illness or gain benefit from chronic disease therapy. For years, pharmacists counseled patients that they had to take all 10 days of their antibiotic or the infection would come back. We now know that is not true. For a variety of common bacterial infections, we now successfully use single dose, 3-day regimens, 5-day regimens, and 7-day regimens to treat bacterial infections that were previously thought to require 10 to 14 days of antibiotic therapy. For chronic disease therapy, an 80% adherence rate has been hailed, albeit without any evidence, as the amount needed to get benefit. However, the original Veterans Administration study that initially demonstrated the efficacy of antihypertensive therapy in preventing complications, such as congestive heart failure, did not measure adherence and used a three times a day medication regimen, which carries an adherence rate of only 60% to 65%. Yet the study still managed to show considerable benefit. Similarly, providers insist that reaching target goals is necessary to get benefits such as preventing diabetic retinopathy, yet studies show that at A1C levels of less than 8.0%, the incidence of retinopathy drops drastically. The ACCORD studies showed that lower targets of glucose and blood pressure related to current guidelines did not have a positive effect on complication rates and even increased the risk of mortality in the lower target groups. Another common provider misconception is that elderly patients have lower medication adherence rates than younger populations. In reality, studies show that while the elderly generally take more medications and have more barriers to adherence, their actual adherence rates are better than younger populations. Finally, many providers feel that educating the patient should be enough to ensure optimal adherence. However, studies repeatedly show that traditional educational programs have little or no effect on medication adherence in asymptomatic chronic diseases.

• REQUIREMENTS FOR MEDICATION ADHERENCE

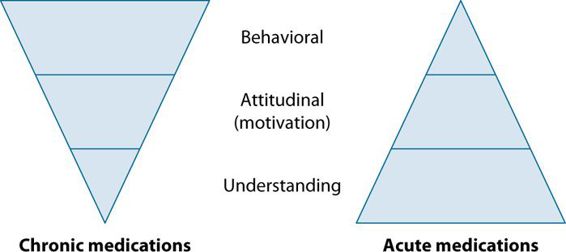

There are three things required for patients to adhere to medication regimens: sufficient understanding of the chronic disease and the medications being used to treat it, motivation to take the medication, and implementation of necessary behavior changes. The impact on adherence to medications for each of these three requirements differs between acute and chronic medications (Figure 5.1). In patients taking acute medication, patient understanding plays a major role, since most patients with acute diseases have symptoms and it is easy to be motivated to take medications that will end the symptoms. Similarly, the behavioral changes (taking medication) are short lived, lasting for only a few days. Therefore, it is not surprising that education and verification of patient understanding have been shown to have a significant impact on subsequent medication adherence in patients with acute symptomatic diseases. In patients with asymptomatic chronic diseases, such as hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia, understanding about their disease and medications is still the foundation for ultimate patient adherence, but has far less impact on subsequent adherence because motivation and behavioral changes are the major forces in determining subsequent medication adherence. Since there are no obvious symptoms of these chronic diseases such as diabetes, it is more difficult for patients to motivate themselves to take medication to prevent some vague future complications. To be motivated to take medication and adhere to medication for prolonged periods, patients must feel and accept that something is wrong with them, feel motivated to prevent future problems by using medication, and believe that the pros of taking medicine will in the long run outweigh the cons. The behavioral aspects are even more daunting, since patients with chronic diseases are required to make lifelong changes in diet and exercise, plus take medications for the rest of their lives. Therefore, it is not surprising that studies show the lack of impact of education alone on medication adherence in patients with chronic asymptomatic diseases. Finally, for adherence to both acute and chronic medications, the traditional “telling people” educational approaches are not effective. The educator must use “teach-back” techniques to verify that patients understand the instructional material by either demonstration or verbalization of their understanding.

FIGURE 5.1 Requirements for medication adherence.

• ASSESSMENT OF RISK FACTORS FOR SUBOPTIMAL ADHERENCE

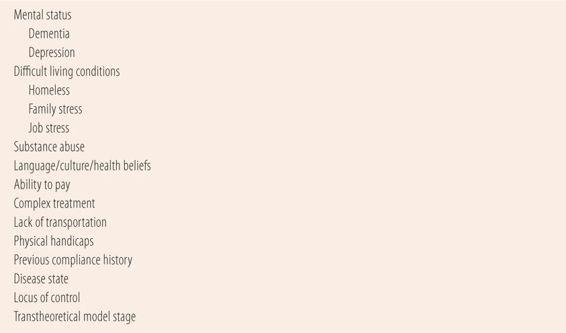

There are multiple theoretical and actual factors that can negatively impact medication adherence issues. Two theoretical tenets have been shown to have impacts on rates of medication adherence (Table 5.2). Locus of control is a concept that deals with patient confidence. Patients with an external locus of control feel that events are either in the hands of a deity or are determined by fate and that they as an individual have little control over what happens. Patients with an internal locus of control feel that they have great influence over what happens to them. Studies have shown that generally patients with an internal locus of control have significantly higher medication adherence rates than patients with an external locus of control. Therefore, an external locus of control is a risk factor. The transtheoretical model describes five stages of readiness for change. Patients in the bottom two stages, precontemplation and contemplation, have not even considered making any changes in behavior and are unlikely to start taking medication. For readers interested in these two theoretical concepts, there are several articles in the Key References section with a more detailed description of both topics.

| TABLE 5.2 | Risk Factors for Suboptimal Medication Adherence |

The remaining risk factors are real world issues that in most cases are fairly obvious to most health care providers (Table 5.2). Patients with mental illness traditionally have had problems with medication adherence. Studies document that the presence of dementia, schizophrenia, or depression markedly increases the risk for suboptimal adherence. Studies in patients with substance abuse issues also show significant problems adhering to therapeutic regimens. Difficult living conditions also negatively impact medication adherence. Homeless patients many times have nowhere to store medications, low income, and nominal daily routine. In addition, a significant percentage of the homeless have been diagnosed with some type of mental illness, plus their medications are constantly at risk for theft. Similarly, job or family stress makes it difficult to remember to take medications in a timely fashion. Patients with language barriers, cultural factors, and different health beliefs are also at greater risk for adherence problems. The cost of medication is one of the most significant risk factors for poor adherence. Every pharmacist has had patients ask for advice about which of their several chronic medications they could go without due to excessive cost. Prescribers many times use expensive branded medications when older, but therapeutically equivalent generic medications would be just as effective. Therefore, due to similar efficacy and lower cost, cheaper generic medications should always be initially prescribed, unless no other effective or safer alternatives

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree