Chapter 34 Cutaneous cysts

Although a wide variety of cysts may present in the skin, usually these turn out to be epidermoid (infundibular), trichilemmal or glandular in nature (Table 34.1). It can sometimes be difficult to determine whether a structure is a true cyst, a sinus, a comedone or an obliquely sectioned dilated hair follicle. Usually the clinical information or further sections provide the answer, but the alternatives should always be borne in mind. The majority of cutaneous cysts are recognized as such clinically. However, a significant proportion of misdiagnoses do occur; therefore, it is advisable that all lesions are submitted for histological confirmation.1,2

Table 34.1 Classification of cutaneous cysts

| Keratinizing | Glandular |

|---|---|

| Epidermoid | Bronchogenic |

| Proliferating epidermoid | Thyroglossal duct |

| Hybrid cyst | Branchial |

| Verrucous | Cervical thymic |

| Epidermoid cyst of the sole | Ciliated |

| Comedonal | Median raphe |

| Milia | |

| Trichilemmal | |

| Vellus hair | |

| Steatocystoma | |

| Dermoid |

Follicular cysts

Most cutaneous cysts are derived from the pilosebaceous unit. Thus epidermoid, pigmented follicular and vellus hair cysts and milia are each derived from the follicular infundibulum.1 Pilar (trichilemmal cysts) are believed to originate in the follicular isthmus of anagen hairs. Steatocystoma is a cyst of the sebaceous duct. Cystic pilomatrixoma is derived from hair matrix cells and hybrid cysts can originate from any of the above.1

Epidermoid cyst

Clinical features

Epidermoid (epidermal, infundibular) cysts, which occur particularly on the face, neck, and upper trunk, are believed to result from damage to the pilosebaceous units.1 The vulval labia majora and scrotum are also sites of predilection. Young and middle-aged adults are most often affected and the sexes are involved equally. Epidermoid cysts present as smooth dome-shaped swellings a few millimeters to a few centimeters across (Fig. 34.1). A punctum is usually present (Fig. 34.2).

Fig. 34.1 Epidermoid cyst: a typical dome-shaped swelling with two puncta.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Fig. 34.2 Epidermoid cyst: close-up view of a punctum.

By courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

The presence of multiple lesions may suggest the possibility of Gardner’s syndrome, which includes polyposis coli, jaw osteomas, and intestinal fibromatoses in addition to cutaneous cysts.2,3 Less frequently, patients may manifest lipomas, pilomatrixomas (including epidermoid cysts with pilomatrical lining), and leiomyomas.

Multiple and often large epidermoid cysts are sometimes seen as a complication of ciclosporin therapy in transplantation recipients.4,5 Multiple epidermoid cysts have also been described in association with imiquimod therapy.6

Epidermoid inclusion cysts may also complicate penetrating trauma to the skin, such as by a sewing needle, with resultant implantation of squamous epithelium into the dermis (Fig. 34.3).7,8 Lesions may rarely develop after genital mutilation,9 after vaccination (BCG),10 and after cosmetic surgical procedures including penile girth enhancement therapy11 and abdominoplasty.12

Pathogenesis and histological features

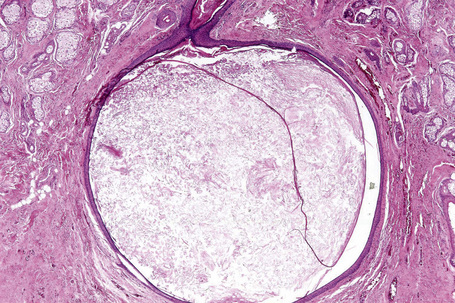

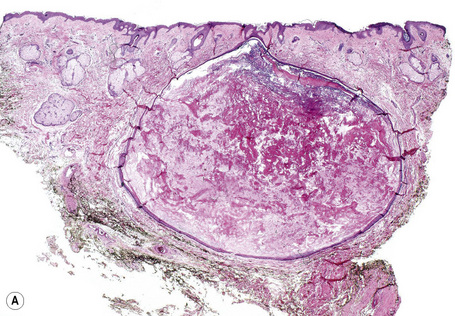

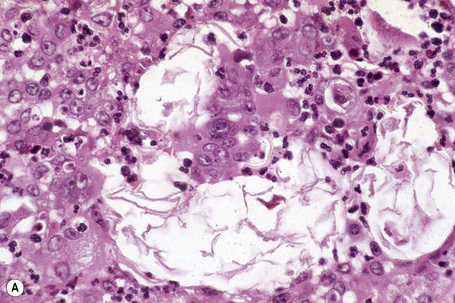

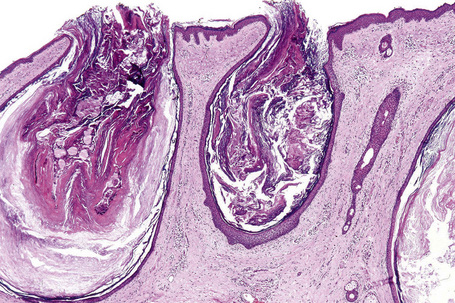

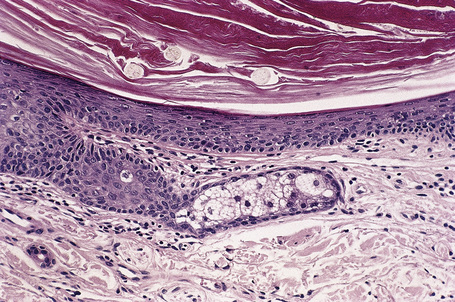

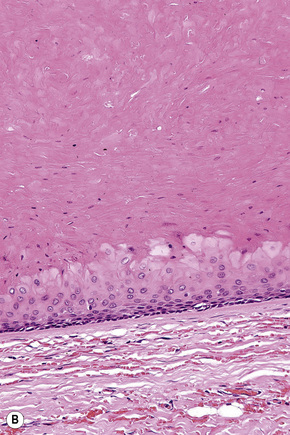

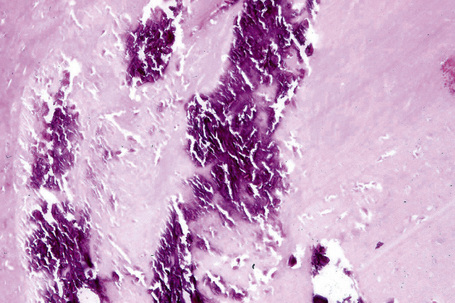

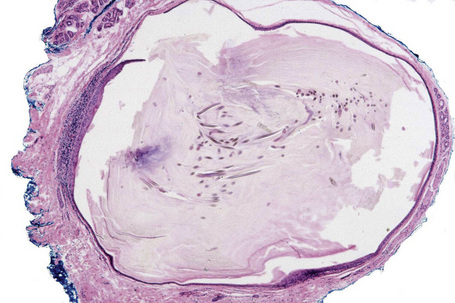

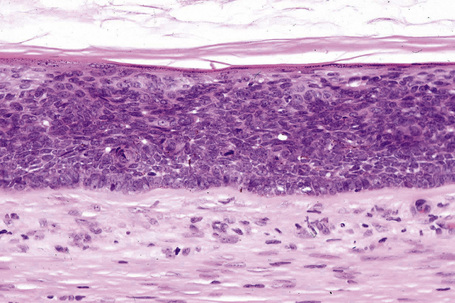

Epidermoid cysts are unilocular, spherical, and are lined by an epidermis-like epithelium including a granular cell layer (Figs 34.4–34.6).1 Exceptional multilocular lesions may occur.13 The cyst contents of laminated keratin are believed to represent follicular infundibular derivation (the nonimplantation variant). In older lesions the lining is often somewhat attenuated. Acute inflammation may result in the subsequent disruption of the cyst wall, with the development of an intense foreign body giant cell reaction (Fig. 34.7). Sometimes this may be so marked that it completely destroys the cyst and only focal dermal collections of keratin fragments remain (Fig. 34.8). It is not clear whether bacteria play an important role in the development of inflammation in epidermoid cysts. A study from Japan found an increased incidence of anaerobes in inflamed lesions as opposed to those without inflammation.14 It is not clear, however, whether this is the result of colonization or a true infection. Occasionally, the cyst lining may show epidermoid and focal trichilemmal keratinization. In the rare hybrid cyst there is epidermoid keratinization in the superficial half of the cyst and trichilemmal in the lower.15 Exceptionally, a pigmented variant containing multiple terminal hair shaft fragments may be encountered (pigmented follicular cyst).16,17 A case with numerous keratin spherules has been reported.18

In patients with Gardner’s syndrome, the cyst lining occasionally shows focal basaloid cell proliferation with ghost cell change, as seen in pilomatrixoma (Fig. 34.9).19,20 These were once thought to be pathognomonic of Gardner’s syndrome, but they have now been described outside of this context, including a case arising in a background of nevus sebaceous.21,22 Thus, while highly suggestive, these cannot be considered pathognomonic.

Epidermoid cysts not uncommonly coexist with melanocytic nevi. This is of particular importance, as the resulting increase in size of the cyst may raise clinical suspicion of melanoma.23,24 Most nevi are banal and dermal but cysts associated with compound nevi, congenital nevi, dysplastic nevi, blue nevi, and spindle cell nevi of Reed have also been documented.24

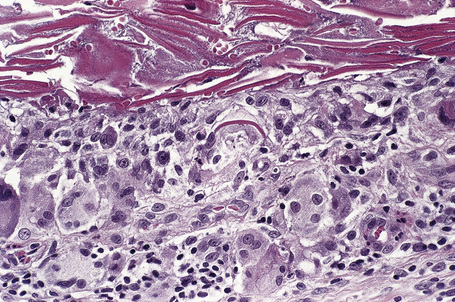

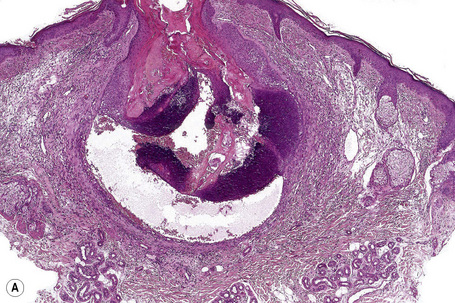

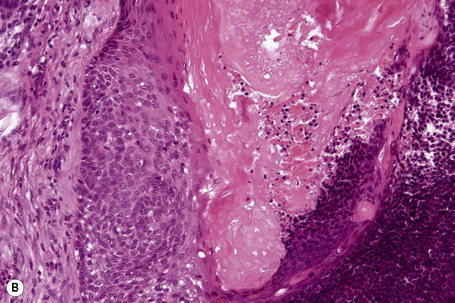

Malignant tumors may rarely develop within the wall of an epidermoid cyst including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Fig. 34.10).25–30 There are also single case reports describing an epidermoid cyst in association with Paget’s disease and cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma.31,32 There have been no cases reported of melanoma arising in cutaneous lesions, although in situ melanoma associated with an adjacent cutaneous melanoma has been reported to colonize an epidermoid cyst and there is a single report of it arising in a noncutaneous cerebellopontine angle epidermoid cyst.33,34 Pilomatrixoma (in the absence of Gardner’s syndrome) in conjunction with an epidermoid cyst has also been documented.35 Because epidermoid cysts with malignant change cannot be clinically reliably distinguished from their extremely common benign counterpoints, histologic examination of all such cysts is recommended.36

Fig. 34.10 Epidermoid cyst: in this example, the epithelial wall shows the features of carcinoma in situ.

Epidermoid cysts showing features of a range of cutaneous dermatoses have been described.37 These include psoriasis, lichen planus, and Darier’s disease.38–40 Changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis and involvement by molluscum contagiosum have also been described.41,42 Human papillomavirus (HPV) associations are described below (see verrucous cyst).

Proliferating epidermoid cyst

Clinical features

Proliferating epidermoid cyst is rare and poorly documented, the majority of cases, in fact, describing the pilar/trichilemmal variant.1,2 There are, however, very occasional reports of this entity, of which the comprehensive review from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology is the most informative.3,4

The tumor shows a predilection for males (1.8:1) and although a wide variety of sites may be affected, the majority appear to present on the pelvic area, scalp, and trunk in descending order of frequency.4 Most patients are middle aged or elderly (range: 21–88 years, mean: 54 years). Occasional patients document the presence of a lesion for several decades, giving support to the concept that the resulting tumor has developed within a pre-existent benign epidermoid cyst.4 In this series, proliferating epidermoid cyst was associated with a 20% recurrence rate but metastases were not encountered.4

Histological features

By definition, focal cyst wall lined by stratified squamous epithelium and showing a granular cell layer with epidermoid/infundibular keratinization must be evident. The proliferating component is variable and ranges from well-differentiated squamous epithelium with conspicuous squamous eddies reminiscent of inverted follicular keratosis through to multicystic, keratotic, and verrucous lesions.4 Rarely, frank invasive carcinoma is encountered.

Hybrid cyst

The term hybrid cyst was originally introduced to describe a cyst in which the upper half showed features of an epidermoid cyst whereas the lower portion comprised a trichilemmal cyst.1 There was a sharp distinction between the two linings. The spectrum was subsequently expanded to include cysts with a variety of dual linings including epidermoid cyst and pilomatrixoma, trichilemmal cyst and pilomatrixoma, epidermoid with both trichilemmal and pilomatrical features, and eruptive vellous hair cyst with trichilemmal cyst.2–4

There are also a number of reports of cysts combining the features of eruptive vellus hair cyst and steatocystoma.2,5–8 These are intriguing, given the potentially shared molecular pathogenic features of these processes likely involving keratin 17. Epidermoid cyst with apocrine hidrocystoma and pilomatrixoma with cystic trichilemmoma have also been described.9,10 Hybrid cysts with follicular and apocrine differentiation seem to be more common on the eyelid.11 Since all of these cysts are derived from various components of the hair follicle, their combination is not surprising. The characteristic cyst of Gardner’s syndrome, in which epidermoid features merge with pilomatrixoma, can also be regarded as a type of hybrid cyst.12

Verrucous cyst

Clinical features

The verrucous cyst is a variant of epidermoid cyst associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.1–5 Adults are affected and lesions may present at a wide variety of sites although the face, back, and (to a lesser extent) the arms and chest are most often involved.5 The sexes are affected equally. The cysts show no particular distinguishing clinical features.4

Pathogenesis and histological features

Verrucous cysts are associated with HPV infection as determined by polymerase chain reaction.3,4 Thus far, HPV antigens have not been identified with immunohistochemistry. The subtype is unknown in most cases, but a single lesion with the HPV type 59 has recently been described.6 An unusual case of multiple verrucous cysts associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated HPVs (20, 24, alb-7, and 80) and epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like epidermal lesions in the setting of idiopathic CD4 lymphopenia (immunosuppression) has been described.7

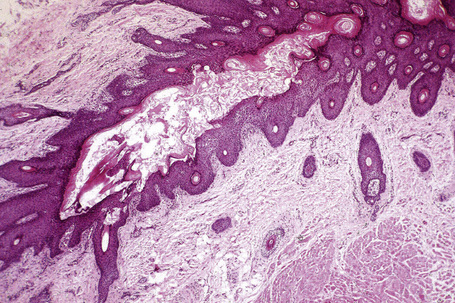

Histologically, verrucous cyst shows focal features of a typical epidermoid cyst and rarely features of a trichilemmal cyst.8 The greater part of the cyst wall, however, is lined by papillomatous, acanthotic squamous epithelium with hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and conspicuous hypergranulosis. Keratohyaline granules are enlarged and irregular, and occasionally koilocytes are seen.2,3,5 In some lesions, the epithelium consists of an admixture of basaloid and squamous cells, and squamous eddies are prominent.3 A lymphohistiocytic infiltrate is sometimes present in the surrounding dermis.

Epidermoid cyst of the sole

Clinical features

Epidermoid cyst of the sole has been described mainly in the Japanese.1–5 A single case report documents the lesion in a non-Japanese.6 Involvement of the palm has also been reported.4 The cyst likely represents an implantation variant.7 It is of particular interest as it has been shown to be associated with HPV infection in some cases.5 An exceptional giant lesion extending from the sole into the dorsum of the foot through the interosseous muscles has been described.8

Histological features

Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions in the wall of the cyst and vacuolated cells in the keratin layer.2,5 Parakeratosis with absence of the granular cell layer is sometimes noted in the more superficial portion of the cyst.9 The cyst is filled with orthokeratotic keratin. Immunoperoxidase confirms the presence of viral antigen and inclusions have been identified ultrastructurally.2,5 HPV 60 has been demonstrated.10

Comedonal cyst

Clinical features

Acne, including chloracne (a condition characterized by the development of acneiform lesions in patients following exposure to the halogenated hydrocarbons), is the commonest cause of comedone formation. Comedones are follicular retention cysts.1 When they open directly onto the surface, a blackhead is visible clinically (Fig. 34.11). If the ostial canal is blocked, pigmented keratin is not visible and the medium-sized whitish papule is classed as a closed comedone or whitehead (Fig. 34.12).

Fig. 34.11 Acne vulgaris: (A) typical open comedones (blackheads); (B) close-up view. (A)

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, St George’s Hospital, London, UK; (B) by courtesy of the Institute of Dermatology, London, UK.

Pathogenesis and histological features

Follicular dilatation and hyperkeratosis (follicular plugging) are common features of facial skin. The development of an acne microcomedone is a further extension of that process. The fully developed blackhead contains abundant laminated keratin and cellular debris (Fig. 34.13). A large sebaceous gland with a small hair may be attached to the widely distended but patent follicle. If the lesion persists, the sebaceous gland and hair commonly atrophy (Fig. 34.14). A histological section through a closed comedone will often miss the blocked connection with the epidermis and sometimes a blackhead may appear as an intradermal cyst.

Differential diagnosis

Solar comedones (Favre-Racouchot disease) occur as a clinical triad of cysts, comedones, and elastosis around the orbit and malar areas of elderly patients, and are due to prolonged exposure to sunlight (Fig. 34.15).2 Rarely, a plaquelike lesion may be seen.3 Large thin-walled open and closed comedones are present in the upper dermis, accompanied by marked solar elastosis.4 A small series of cases of what is regarded as a variant of Favre-Racouchot disease and including epidermoid cysts with vellus hairs and solar elastosis and presenting on the ears has been described.5

Open and closed comedones are also a feature of the congenital conditions familial comedones and familial dyskeratotic comedones. Both of these have an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance; the former is characterized by a greater number of lesions and an absence of dyskeratosis.6–8. Rarely, late-stage follicular mucinosis and discoid lupus erythematosus may feature large thin-walled comedones as the dominant histological component.

Milia

Clinical features

Milia are common superficial keratinous cysts that present as white or yellow dome-shaped nodules measuring 1–3 mm in diameter.1,2 They may represent primary lesions when no cause can be identified or secondary variants usually following skin trauma or other injury.

Primary milia are seen in up to 50% of newborns and present on the face, upper trunk, and extremities.3 These typically regress spontaneously. Children and adults can also be affected, when lesions are most often apparent on the face (forehead, eyelids, and cheeks) and the external genitalia (Fig. 34.16).3 Possible association of persistent infantile milia with steatocystoma multiplex and eruptive vellus hair cysts has also been suggested.4

Secondary milia may complicate a wide range of conditions including follicular mucinosis, folliculotropic mycosis fungoides, lichen sclerosus, radiotherapy, herpes zoster infection, leishmaniasis, severe burns, dermabrasion, chemical peeling, cutaneous local steroid therapy, adverse drug reactions (e.g., benoxaprofen), and contact dermatitis.3,5–15 Milia are also a feature of a number of subepidermal blistering disorders including dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, porphyria cutanea tarda, and pseudoporphyria. They may also be a feature of a variety of familial dermatoses including Rombo’s syndrome (facial anetoderma vermiculatum, telangiectasia, milia, hypotrichosis, acral erythema, cyanosis and tendency to develop trichoepitheliomas and basal cell carcinomata), Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome (follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, basal cell carcinomas), and familial multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, milia and spiradenomas.16–18

Rarely, milia present as a localized plaque variant (milia en plaque).3,19–25 Such lesions are most often described around the ears. A small number of cases involving the eyelids have been documented and there is one supraclavicular example.20 One case that developed in a background of pseudoxanthoma elasticum has been described.21 A further example in association with lupus erythematosus has also been reported.26 In the small number of documented cases, the sex incidence is equal and a wide age range has been affected (12–62 years). There is no racial predilection.23 Patients present with an edematous, erythematous plaque studded with numerous milia.

Very occasional examples of eruptive milia have been described including rare cases in children.4,27–29 Recently these have been classified into spontaneous and autosomal dominant familial variants.30 They may also represent a component of a genodermatosis.4

Pathogenesis and histological features

Milia consist of miniature epidermoid cysts located in the superficial dermis just underneath the epithelium (Fig. 34.17). Attachment to a vellus hair follicle is often seen in the newborn variant. Secondary lesions may be related to hair follicles or an eccrine sweat duct. The latter are typically seen in milia associated with scarring blistering diseases.

The etiology of milia en plaque is unknown although spectacles, earrings, and perfume have been suggested as possible causes.22–24 In this variant, a background dense T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate is typically present.22,23

Trichilemmal cyst

The outer root sheath of the hair follicle at the level of the follicular isthmus is recapitulated in the wall of trichilemmal (pilar) cysts.1–3 It has been suggested that these cysts should be renamed as isthmic-catagen cysts. Their origin is unknown, but it has been suggested that they are produced by budding off from the external root sheath as a genetically determined structural aberration. Familial occurrence is seen in 75% of patients, in a pattern suggesting autosomal dominant inheritance.4

Clinical features

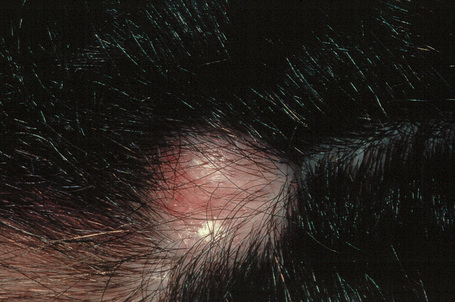

Trichilemmal cysts are found on the scalp in 90% of cases; they are solitary in 30% and multiple in 70% (Fig. 34.18).4 Unusual sites such as the pulp of a finger have been reported.5 They present as smooth, yellowish, dome-shaped intradermal swellings and are more common in females (Fig. 34.19). In contrast to epidermoid cysts, they are characteristically devoid of a punctum. It should be noted that the term ‘sebaceous cyst’ favored by many clinicians is a misnomer because such lesions represent either epidermoid or trichilemmal cysts. Typically, the cyst is encapsulated and uncomplicated lesions readily ‘shell out’ at surgery.4 Acute inflammation is uncommon and when it does occur is usually of nonbacterial origin; its presence makes excision more difficult, with an increased likelihood of rupture. An exceptional case of a lesion presenting as an organoid nevus, following Blaschko’s lines and showing multiple trichilemmal cysts on histologic examination, has been described as trichilemmal cyst nevus.6

Fig. 34.18 Trichilemmal cyst: note the characteristic dome-shaped swelling on the scalp, a typical site.

By courtesy of A. du Vivier, MD, King’s College Hospital, London, UK.

Histological features

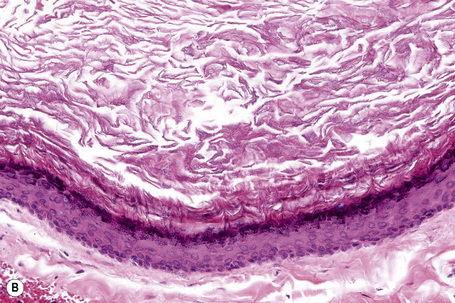

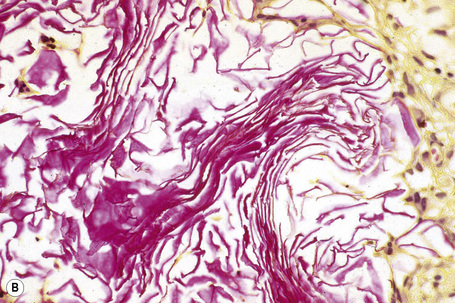

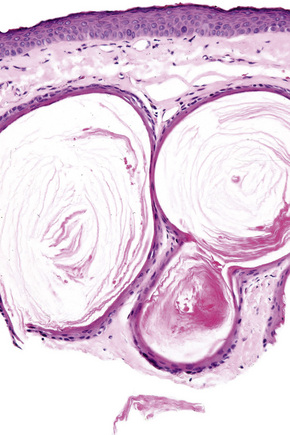

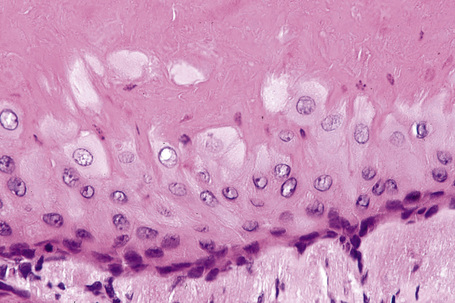

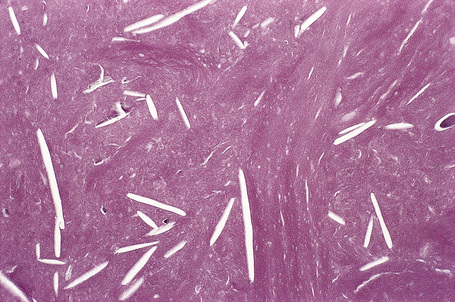

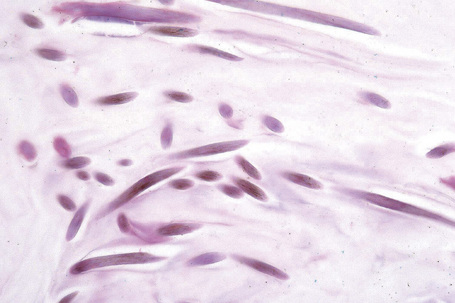

The cyst is surrounded by a fibrous capsule against which rests a layer(s) of small dark-staining basal cells. These merge with characteristic squamous epithelium composed of pale keratinocytes, which increase in height as they mature and transform abruptly into solid eosinophilic-staining keratin without forming a granular cell layer (Figs 34.20–34.22). Occasionally, small foci of epidermal keratinization (i.e., with a granular cell layer) may also be identified. Calcification occurs in 25% of lesions, regardless of the age or size of the cyst, and cholesterol clefts occur in up to 90% (Figs 34.23, 34.24).1,4 Secondary inflammation is manifest as an influx of inflammatory cells into the lumen of the cyst, in contrast to the granulomatous response that may surround an epidermoid cyst. In a small percentage of cases there is budding of tiny daughter cysts from the parent.7 Very rarely, sebaceous and apocrine differentiation are found in the cyst wall.8 Exceptional cases of other neoplasms such as Merkel cell carcinoma colonizing or arising in a trichilemmal cyst have been reported.9,10

Fig. 34.20 Trichilemmal cyst: this shows the typical macroscopic appearance of cheesy lamellated contents.

Vellus hair cysts

Clinical features

Vellus hair cysts were originally reported in children and young adults of both sexes.1–4 The sex distribution is equal and there is no racial predilection. Patients present with numerous asymptomatic, discrete, soft, flesh-colored or reddish-brown papules, 1–5 mm across, particularly over the parasternal area, although the distribution may be quite widespread.4 A generalized distribution has recently been documented.5 An exceptional case mimicking a nevus of Ota has been described.6 Lesions may rarely be unilateral.7 Occasional lesions are umbilicated, and squeezing may express white caseous material. Further cases have expanded the condition to include an inherited (autosomal dominant) variant, which may or may not be manifest at birth and is more likely to occur over the extensor aspects of the limbs.3,8 A facial form and a patient presenting with a periorbital distribution have been described.9–11 Spontaneous involution is not uncommon.2,12

Vellus hair cysts have occasionally been associated with renal failure and a number of genodermatoses including pachyonychia congenita, anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia and, rarely, Lowe syndrome (oculocerebrorenal syndrome characterized by Fanconi-type renal failure, mental retardation and ocular abnormalities).13–17 Occasionally, solitary lesions are encountered.

Pathogenesis and histological features

Eruptive vellus hair cysts most probably develop as a consequence of occlusion of the infundibulum of vellus hairs with resultant cystic dilatation and retention of keratinous debris and vellus hairs.2 The primary cause of the obstruction is unknown. It has also been proposed that they represent follicular hamartomas.8 Studies indicate that both eruptive vellus hair cysts and steatocystomas express keratin 17, with the latter also expressing keratin 10.18,19 This overlap in keratin expression may help explain the underlying similarities and perhaps overlapping features of these two lesions, but this opinion is not universal, their exact relationship remains to be elucidated.20–22

The characteristic histology is that of a mid-dermal cyst containing laminated keratin and many vellus hairs (Figs 34.25, 34.26).2,4,12 The epithelial lining consists of several layers of squamous epithelium, often with a granular cell layer. Sometimes the cyst is in continuity with the epidermis, an atrophic follicle or a pilomotor muscle.3,4,12 Vellus hair cysts are more likely to open onto the surface in the congenital variant. Occasionally the cyst ruptures and there is an associated foreign body giant cell reaction.

Differential diagnosis

Eruptive vellus hair cysts show very marked clinical overlap with steatocystoma multiplex and can only be distinguished by histological analysis.23 Steatocystoma is characterized by an epidermoid lining without a granular cell layer. The innermost aspect of the cyst wall is covered by an undulating eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous glands are present in the wall of the cyst or in the immediate vicinity.

Sometimes, however, patients have both types of cyst simultaneously and occasionally there are overlapping histological features sometimes constituting a hybrid cyst.24,25

As noted above, differential keratin expression has been shown to distinguish the two cysts. Thus vellus hair cyst expresses K17 but not K10 whereas steatocystoma expresses K17 and K10.26 Interestingly, mutations in the KRT17 gene can cause both pachyonychia congenital type 2 and also a condition very similar or identical to steatocystoma multiplex.27,28 The relevance of these findings to steatocystoma simplex and vellus hair cysts, if any, remains to be determined.

Dermoid cyst

Clinical features

Dermoid cysts result from the sequestration of cutaneous tissues along embryonal lines of closure.1–5 The most common clinical appearance is that of a single nontender small subcutaneous nodule at birth on the lateral aspect of the upper eyelid (Fig. 34.27). Although slow enlargement is the rule, sometimes a sudden increase in size may occur, bringing the lesion to attention at a later age. Other potential sites of dermoid cysts include the midline of the neck, nasal root, nose, forehead, the mastoid area, anterior chest, and scalp.3,6,7 The last is a particularly important site as the lesion may very occasionally show intracranial extension (dumbbell dermoid).3,4 Midline occipital lesions are most often affected.3 Dermoid cysts may also present on mid chest, sacrum, perineum, and scrotum.5 Dermoid cysts are also encountered in deeper noncutaneous sites.

Fig. 34.27 Dermoid cyst: note the swelling adjacent to the upper eyelid – the external angular dermoid cyst.

By courtesy of R.A. Marsden, MD, St George’s Hospital, London, UK.

Infection of a cranial dermoid cyst is a serious development as it may be complicated by central nervous system involvement.3 Squamous cell carcinoma very rarely develops in the wall of the cyst.8,9

There are occasional reports of familial dermoid cysts, including one family associated with midline cleft lip.10–12

Pathogenesis and histological features

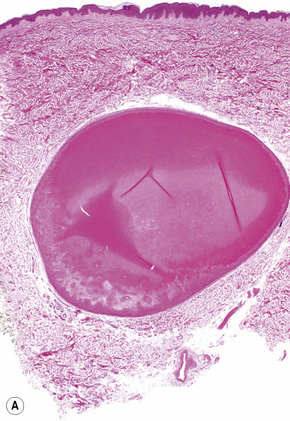

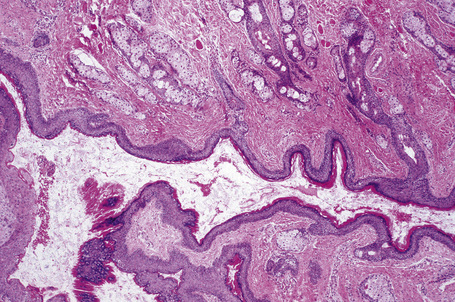

The unilocular cysts are usually subcutaneous and may be attached to the periosteum. They are lined by stratified squamous epithelium with associated hair follicles and sebaceous glands (Fig. 34.28). Eccrine sweat glands are present in 35% of cases and apocrine glands in 15%. Smooth muscle can be present but – in contrast to benign cystic teratoma – cartilage and bone are not described. Some authors propose an embryological origin for these cysts, particularly in the nasal form.13

Glandular cysts

Bronchogenic cyst

Clinical features

Bronchogenic cysts presenting in the skin are very rare, with fewer than 70 cases reported.1–14 There is a marked predilection for males (4:1).13 Most are situated on the precordium or overlying the suprasternal notch and are usually present at birth.1–3 Occasionally, they are located about the shoulder, back, scapula, neck, abdomen or chin or present at a later age.4 Clinical presentation is variable and includes cutaneous cystic nodules, sinuses, and even a papillomatous growth.4,5 Occasionally, the cysts drain a mucinous fluid.1,8 Most are asymptomatic but some are tender or painful. Exceptionally, multiple lesions may be seen.15

Pathogenesis and histological features

Bronchogenic cysts are believed to form from buds or diverticula that separate from the foregut during the development of the tracheobronchial tree; they may be intrapulmonary or peripheral. Cutaneous bronchogenic cysts may result from subsequent sequestration outside the chest cavity following fusion of the mesenchymal bars of the sternum or else from active migration prior to fusion.13,14 Lesions overlying the scapula likely arose before the scapula developed, at the sixth week of gestation.6

The cutaneous bronchogenic cyst is situated within the dermis or subcutaneous tissue and usually its lining is thrown into small folds. The epithelium is invariably pseudostratified cuboidal or columnar and ciliated, with mucus-secreting goblet cells in about 50% of cases.2,13 Nonciliated cuboidal, columnar, and stratified squamous epithelium may also be identified. Smooth muscle supports the mucosa in 8% of cases.1,12,13 Lymphoid follicles are found in only 25% of cases and then appear to be part of a secondary inflammatory response.1 Seromucinous glands are also sometimes present.2,5,12 Cartilage is evident in a minority of cases.4,6,10,13 Not all of these features are necessarily present in any one particular cyst and the diagnosis may then be in part dependent upon clinicopathological correlation.8,9

Cutaneous lung tissue heterotopia in which fully developed bronchioles and alveoli are present can be regarded as a variant.16

Immunohistochemistry has been only rarely documented. The lining epithelial cells express cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) but not carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA).13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree