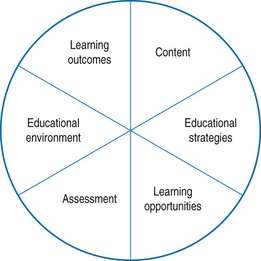

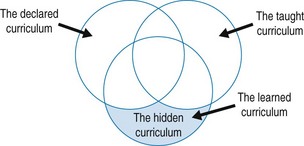

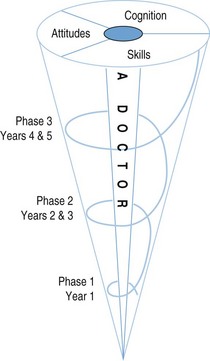

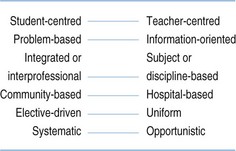

Chapter 2 A curriculum is more than just a syllabus or a statement of content. A curriculum is about what should happen in a teaching programme – about the intention of the teachers and about the way they make this happen. This extended vision of a curriculum is illustrated in Figure 2.1. Curriculum planning can be considered in 10 steps (Harden 1986b). This chapter looks at these steps and the changes in emphasis since the publication of the third edition of the text. The relevance or appropriateness of educational programmes has been questioned by Frenk et al (2010), Cooke et al (2010) and others. The need has been recognized to emphasize not only sickness salvaging, organic pathology and crisis care, but also health promotion and preventative medicine. Increasing attention is being paid to the social responsibility of a medical school and the extent to which it meets and equips its graduates to meet the needs of the population it serves. A range of approaches can be used to identify curriculum needs (Dunn et al 1985): • The ‘wise men’ approach. Senior teachers and senior practitioners from different specialty backgrounds reach a consensus. • Consultation with stakeholders. The views of members of the public, patients, government and other professions are sought. • A study of errors in practice. Areas where the curriculum is deficient are identified. • Critical-incident studies. Individuals are asked to describe key medical incidents in their experience which represent good or bad practice. • Task analysis. The work undertaken by a doctor is studied. • Study of star performers. Doctors recognized as ‘star performers’ are studied to identify their special qualities or competencies. One of the big ideas in medical education over the past decade has been the move to the use of learning outcomes as the driver for curriculum planning (Harden 2007). In an outcome-based approach to education, as discussed in Chapter 18, the learning outcomes are defined and the specified outcomes inform decisions about the curriculum. This represents a move away from a process model of curriculum planning, where the teaching and learning experiences and methods matter, to a product model, where what matters are the learning outcomes and the product. The idea of learning outcomes is not new. Since the work of Bloom, Mager and others in the 1960s and 1970s, the value of setting out the aims and objectives of a training programme has been recognized. In practice, however, long lists of aims and objectives have proved unworkable and have been ignored in planning and implementing a curriculum. But in recent years, the move to an outcome- or competency-based approach to the curriculum with outcome frameworks has gained momentum and is increasingly dominating education thinking. The content of the curriculum can be presented from a number of perspectives: • subjects or disciplines (a traditional curriculum) • body systems, e.g. the cardiovascular system (an integrated curriculum) • the life cycle, e.g. childhood, adulthood, old age • problems (a problem-based curriculum) • clinical presentations or tasks (a scenario-based, case-based or task-based curriculum). No account of curriculum content would be complete without reference to ‘the hidden curriculum’. The ‘declared’ curriculum is the curriculum as set out in the institution’s documents. The ‘taught’ curriculum is what happens in practice. The ‘learned’ curriculum is what is learned by the student. The ‘hidden’ curriculum is the students’ informal learning that is different from what is taught (Fig. 2.2 and see Chapter 7). A spiral curriculum (Fig. 2.3) offers a useful approach to the organization of content (Harden & Stamper 1999). In a spiral curriculum: Much discussion and controversy in medical education has related to education strategies. The SPICES model (Fig. 2.4) offers a useful tool for planning a new curriculum or evaluating an existing one (Harden et al 1984). It represents each strategy as a continuum, avoiding the polarizing of opinion and acknowledging that schools may vary in their approach. In student-centred learning, students are given more responsibility for their own education. What the student learns matters, rather than what is taught. This is discussed further in Chapter 19 on independent learning. It is now appreciated that the teacher has an important role as facilitator of learning and that the student should not be abandoned and needs some sort of guidance and support.

Curriculum planning and development

What is a curriculum?

Identifying the need

Establishing the learning outcomes

Agreeing on the content

Organizing the content

Deciding the educational strategy

Student-centred learning

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Curriculum planning and development