Cricopharyngeal Diverticulum: Open Repair

William R. Carroll

Kirk P. Withrow

DEFINITION

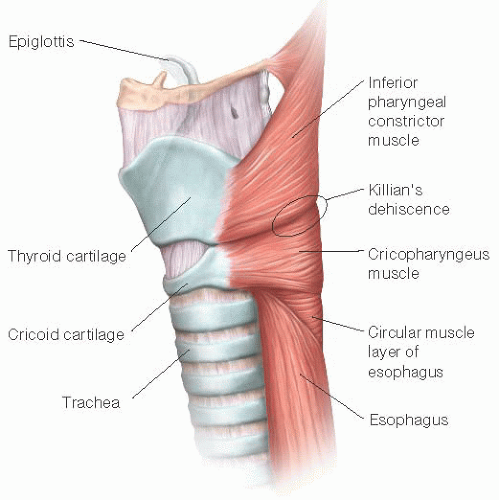

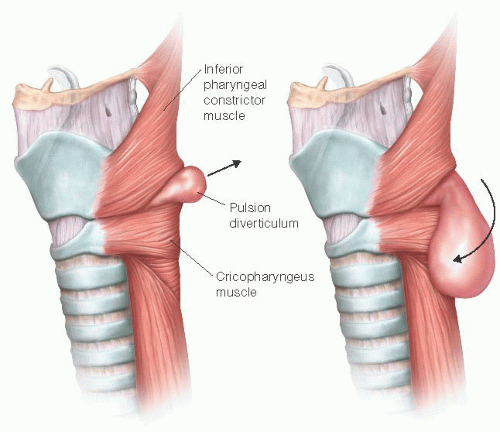

Diverticula of the hypopharynx have been recognized for over 200 years. Zenker’s diverticulum is by far the most common, with an annual incidence rate of 2/100,000 individuals.1 The disorder is acquired rather than congenital and typically occurs in older adults. Men are more commonly affected than women. There are two types of pharyngoesophageal diverticula. Traction diverticula, resulting from a pulling force on the outside of the alimentary tract, are more commonly seen in the mid- to distal esophagus and often result from inflammatory or neoplastic processes adjacent to the muscularis. Pulsion diverticula, such as Zenker’s, result from an internal pushing force causing the mucosa and submucosa to herniate through the muscular wall. Zenker’s diverticula occur where increased intraluminal pressure causes herniation through a deficiency in the muscular layer at Killian’s dehiscence. Killian’s dehiscence is located at the junction of the inferior constrictor and the cricopharyngeus muscles (FIGS 1 and 2).

The history of Zenker’s diverticulum is rich. The anatomy of the pharyngoesophageal junction was first detailed by Antonio Valsalva in 1704. The diverticulum was first described by Abraham Ludlow2 (mentor of Edward Jenner of smallpox fame) in 1764. Sir Charles Bell (Bell’s palsy, Bell’s nerve) described the pathophysiology of uncoordinated hypopharyngeal contraction against a closed cricopharyngeus muscle. The disorder is named for Friedrich von Zenker, a German physician and pathologist, who catalogued 27 cases in 1877.3,4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Zenker’s diverticulum typically presents with dysphagia, regurgitation of undigested food, and occasionally, aspiration pneumonia. Causes for cervical dysphagia in adults may be grouped into three categories: internal, external, and motility. Internal disorders include inflammation and edema, stenosis, and neoplasm. External disorders produce extrinsic compression of the pharyngoesophageal segment and may include thyroid disease, adenopathy, abscess, and congenital cysts. Motility disorders include achalasia, stroke, esophageal spasm, myasthenia, and bulbar palsy.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Cervical dysphagia is the most common presenting symptom of Zenker’s diverticulum. Symptoms may be quite subtle and include chronic cough and unexplained weight loss. As the patient swallows, food and liquids preferentially enter the wide mouth of the diverticular pouch rather than passing through the inappropriately closed upper esophageal sphincter. As food and liquid accumulate, the patient develops a sense of neck fullness and may hear gurgling sounds in the lower neck. A pathognomonic type of regurgitation is common in which the patient regurgitates food minutes or even hours after eating that is completely undigested and not mixed with gastric contents. The pouch may fill and empty spontaneously during deglutition. When the pouch empties, the contents may spill into the airway, causing aspiration with coughing or pneumonia. The aspiration may be subtle and lead to recurrent respiratory infections and eventually chronic respiratory insufficiency. Death due to untreated Zenker’s diverticulum typically results from pulmonary complications.

Physical findings of Zenker’s diverticulum include neck fullness or a mass in the tracheoesophageal groove that may gurgle or decompress with palpation (Boyce’s sign). Audible gurgling may be detected over the same region with swallowing. Inspection of the hypopharynx may reveal pooling of secretions.1 The pouch is typically not visible unless the patient undergoes esophagoscopy.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Barium swallow is usually needed to definitively diagnose Zenker’s diverticulum. The study characteristically reveals a diverticular sac originating just superior to the prominent and poorly relaxing cricopharyngeus muscle. Radiologists describe this prominent muscle as a cricopharyngeal “bar.”

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the neck is unnecessary if barium swallow

confirms a Zenker’s diverticulum. These studies would typically reveal a fluid-filled, cyst-like density adjacent to the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle.

Chest imaging may reveal evidence of chronic aspiration pneumonitis.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for Zenker’s diverticulum. Initially, surgeons sought to control the lesions by creating a controlled pharyngocutaneous fistula. In 1884, Niehans performed the first resection of a Zenker’s diverticulum in Bern, Switzerland, but the patient died within 2 weeks of hemorrhage.4 Wheeler5 in Ireland completed the first successful resection in 1886. Until the mid-1900s, most operations were performed in two stages. In 1945, Harrington6 at the Mayo Clinic reported a series of 107 cases repaired by a single-stage procedure that soon became the standard of care.

Medical therapy with Botox injection of the cricopharyngeus muscle may provide temporary improvement of symptoms.

Contemporary surgeons typically choose between an open and an endoscopic approach. When feasible, most prefer an endoscopic approach initially, citing faster recovery, lower complications, and success rates that are comparable, if not superior, to the open approach.

The most common indication for the open approach is poor endoscopic exposure due to trismus, macroglossia, or spine disorders including osteophytes, kyphosis, or ankylosing spondylitis. Another indication for an open approach is failure of a prior endoscopic approach. Ironically, the most fragile patients are occasionally better candidates for an open approach. When the pulmonary status is particularly poor, the authors and others have used an open approach with local anesthesia successfully.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree