Cricopharyngeal Diverticulum: Endoscopic Repair

Kirk P. Withrow

William R. Carroll

DEFINITION

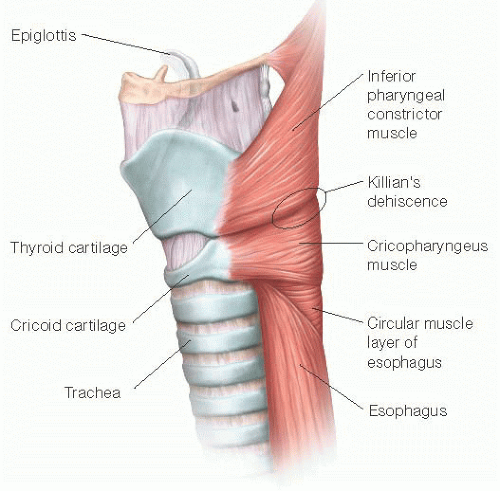

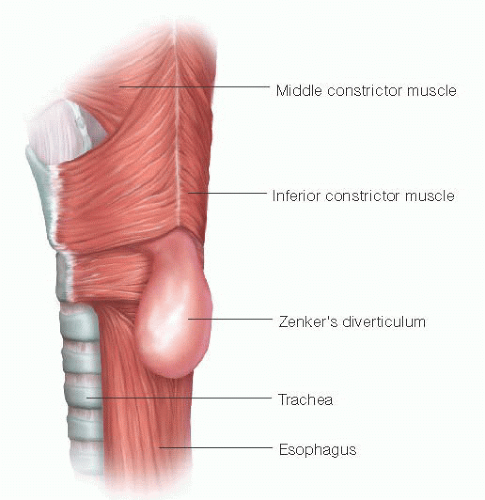

Diverticula of the hypopharynx have been recognized for over 200 years. Zenker’s diverticulum (ZD) is by far the most common with an annual incidence rate of 2/100,000 individuals.1 Specifically, ZD is an outpouching of hypopharyngeal mucosa that occurs at the junction of the inferior constrictor and cricopharyngeus (CP) muscle through a weak area known as Killian’s dehiscence (FIG 1). As it is essentially just a mucosal sac, it is technically considered a “false” diverticulum. This is an acquired disorder that most commonly presents between the sixth and eighth decade of life and affects more men than women. In rare cases, there is a family history of ZD and evidence of genetic predisposition toward its development.2 Although the exact etiology of ZD remains debatable, most agree that it represents a pulsion diverticulum occurring due to a rise in intraluminal pressure relative to the resistance of the esophageal wall. Although manometry data from available studies provide conflicting information about CP muscle activity in ZD patients, clinical observation as well as less favorable swallowing outcomes in patients who did not have a CP myotomy as part of their treatment strongly implicate abnormal CP function in the formation of ZD.

Historically, ZD was first recognized by Abraham Ludlow in 1796 and was named after Friedrich Albert Zenker who reported a series of ZD patients in 1877. The first successful open repair of a ZD was reported by Wheeler in 1882.3 In 1917, Mosher first introduced the concept of endoscopic treatment of ZD that has now seen tremendous advances with respect to both instrumentation and technique.4 The most common method used for treatment of ZD, the endoscopic staple-assist approach, was first reported by Collard in 1993.5

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Achalasia

Esophageal cancer

Esophageal dysmotility

Esophageal spasm

Esophageal stricture

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Thyroid goiter

Myasthenia gravis

Bulbar palsy

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Cervical dysphagia is the most common presenting symptom of ZD. Other symptoms may be quite subtle and include chronic cough, unexplained weight loss, and halitosis. As the patient swallows, the bolus preferentially enters the relatively wider mouth of the diverticular pouch rather than passing through the inappropriately closed upper esophageal sphincter into the esophagus. This in turn may lead to a sense of neck fullness and may be associated with a gurgling sound in the lower neck referred to as cervical borborygmi. Regurgitation of completely undigested food ingested minutes to hours previously is considered near pathognomonic for ZD. The pouch may fill and empty spontaneously during deglutition leading to coughing, choking, and possibly aspiration. Many patients report significant negative psychological and social impact due to a fear of suffering from choking and regurgitation during a meal.

Most commonly, ZD patients present with a normal physical exam. When an abnormality is present, it is generally a neck mass in the tracheoesophageal groove that may gurgle or decompress with palpation (Boyce’s sign). Audible gurgling may be detected over the same region with swallowing. Inspection of the hypopharynx may reveal pooling of secretions. Visualization of the pouch is generally only possible via esophagoscopy.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Barium swallow is the primary study used in the diagnosis of ZD. A characteristic sac is noted just posterior to the esophagus (FIG 2). It arises just superior to a prominent

CP muscle often termed a CP “bar.” With this study, the surgeon can accurately size the sac and determine its location. Some authors recommend obtaining manometry testing on all ZD patients; however, that is not the practice of the authors. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are not generally needed in these patients.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Decision Making

The first decision a ZD surgeon has to make is whether to offer the patient surgery at all. If a patient is minimally symptomatic and of advanced age, then continued observation may be the best course of action. Medical therapy with botulinum toxin aimed at treating CP muscle achalasia is another option, although the benefit of this in ZD is much more limited than that seen in CP dysfunction without diverticulum. On the other hand, if surgery is to be offered to the patient, the surgeon should be capable of performing both open and endoscopic approaches and should clearly delineate the pros and cons of each. With an open approach, there is a cervical scar, longer surgical time, longer recovery, and longer delay to eating but potentially higher rates of symptom improvement and a lower rate of recurrent symptoms. With an endoscopic approach, there is no cervical scar, there is shorter surgical time, and most patients can resume eating the same day. Unfortunately, it is associated with a rate of recurrence as high as 10% in some reports.6 The increased rate of recurrence is understandable as the act of dividing the common wall between the diverticular sac and the esophagus, and thus the CP muscle contained therein, does not always result in a complete CP myotomy. It is the belief of the authors that the rate of recurrence after an endoscopic repair may, at least in part, be directly related to the amount of CP muscle left intact.

The primary anatomic considerations for an endoscopic repair include (1) factors related to exposure and (2) size of the diverticulum. Bloom et al.7 reported unsuccessful exposure in 30% in a series of 30 patients in 2010. Shorter neck, shorter hyomental distance, and increased body mass index (BMI) showed significant correlation with failed exposure, whereas the presence of maxillary teeth trended toward significance. Further diminished cervical mobility and trismus may also hinder successful endoscopic exposure. With respect to the size, it is generally felt that very small (<2 cm) and very large (>4 cm) diverticulum may be best treated via an open approach. In the case of a small diverticulum, this is due to difficulty in engaging and grasping the common wall between the ZD and esophagus. Various modifications to the endoscopic technique address this and include using carbon dioxide (CO2) laser or Harmonic scalpel, modifying the tip of the stapler to allow the blade and staples to be deployed closer to the tip of the device, and using traction sutures to pull the diverticulum into the jaws of the stapler.8 The concern with a very large diverticulum is that the large, redundant, hypotonic sac may lead to persistent symptoms of dysphagia, although this is only anecdotal at present. Visosky et al.9 reported a series 61 ZD patients who underwent endoscopic treatment and noted the main risk factors for recurrence were size larger than 3 cm and the associated amount of redundant mucosa noted after repair.

Operative Management—Endoscopic Approach

The successful treatment of ZD via an endoscopic approach, much like the open counterpart, includes two components: a cricopharyngeal myotomy and management of the diverticular sac. In contrast to an open repair in which a myotomy is performed followed by management of the diverticulum itself, these occur simultaneously when performing an endoscopic repair. Essentially, the “common wall” or septum between the diverticulum and esophagus is divided, leading to the creation of a “common cavity.” Structurally, the common wall is composed of the CP muscle with the herniated mucosa draped over it. In this sense, the two primary goals of ZD surgery can be achieved via an endoscopic approach, but they cannot be separated from one another.