5

Chapter Outline

| 1. | Introduction |

| 2. | Clinic Operations |

| 3. | Policy and Procedures |

| 4. | Chapter Summary |

| 5. | References |

| 6. | Web Resources |

| Web Toolkit available at www.ashp.org/ambulatorypractice |

Chapter Objectives

1. List at least four clinic operation considerations that should be pursued when creating a new pharmacist service.

2. Discuss the various clinic policy and procedure documents that are required rather than optional.

3. Discuss the purpose and recommended content for a billing procedure document.

Introduction

Congratulations on getting approval to start a new clinical pharmacy service! There are numerous next steps, and with thoughtful planning you will be on your way to seeing your first patient in a few months. We have attempted to categorize the many next steps into four tracks: clinic operations, policy and procedures, legal, and billing. The first two tracks are discussed in this chapter, and the latter two are discussed in Chapter 8. The goal is to pursue all four tracks simultaneously to optimize efficiency and effectiveness.

Clinic operation considerations include everything from getting your exam room set up to developing the process for how patients flow through your clinic.1,2 The key when traveling down this track is to use your organization’s resources and procedures that already exist. In a physician’s office, as in our Dr. Busybee sample case, develop clinic operations that mimic the processes of your referring physicians. To maintain your service efficiency, it is important to use existing clinic support staff in the same manner and in the same roles as the clinic physicians use them. If this is done from the beginning as an expectation, the road ahead will be much smoother. Clinic operation considerations in a community pharmacy setting vary significantly and depend primarily upon space and ancillary staff options available.

| The point remains the same: try to use already established processes and current staff roles as much as possible. |

Policy and procedure considerations involve developing required and recommended processes and paperwork. Often, developing policy and procedures is the easiest and least time consuming of the four tracks to complete. You may find policy and procedures to be the most tedious of activities; however, in the end you will be thankful that you spent the time developing them. Policy and procedures maintain a standard of quality, help in training new personnel, and keep everyone on the same page with regard to processes and services, which is especially important as you grow. Usually, policy and procedures can be addressed near the end of your program development, such as for a small private physician-based clinic. However this may not be the best strategy in a large organization such as a community chain pharmacy-based clinic or a hospital-based clinic. In these latter practice settings, the process for getting policy and procedure documents approved may be time-consuming. For this reason, we recommend that you at least become familiar with what is both required and recommended early on so that there are no surprises at the end that delay your grand opening.

Clinic Operations

Clinic operations involve addressing tasks that impact the proposed clinical service on a day-to-day basis at the practice site. This includes (1) office space considerations, (2) clinic scheduling, (3) clinic work flow, and (4) training and credentialing.3–6

Office Space Considerations

It is imperative that the practice site at which you are intending to establish services has office and exam room space for you. To protect patient privacy, finding space away from other patients, health care providers, and the public is imperative because waiting rooms, counters, and front windows are not considered ideal locations for patient visits to occur. Flexibility is needed. For instance, the situation may indicate that an extra exam room is available on Wednesdays and Fridays or that a rotating exam room is available 2 days a week. In most ambulatory patient care settings, space availability is a premium commodity and depends on the patient load of other clinic providers. You may also find space currently not being used that could be converted into an exam room (for example, a medical records room that is being vacated due to practice’s conversion to an electronic medical record system). It is essential for you to see the space to ensure it will meet your needs. Remember, if you plan to have pharmacy students, residents, or fellows at your practice site, plan for the additional space they will need.

CASE

After all the background work and approval of your business plan, you are now ready to get started seeing patients in the new setting. First, however, you must secure adequate space to see the different types of patients Dr. Busybee and you have agreed to serve. Dr. Busybee and you meet with the office manager and decide that Wednesday mornings and afternoons would be the best initial time to add you to the rotation for seeing patients. This day is not as busy in the clinic since several of the physicians take the day off. The office manager suggests that you be treated just like all other practitioners in the office and follow the same rooming procedure used for the physicians and the nurse practitioner. Two exam rooms are allocated, one for anticoagulation management checks and another for medication therapy management (MTM), where you will first focus on diabetes management.

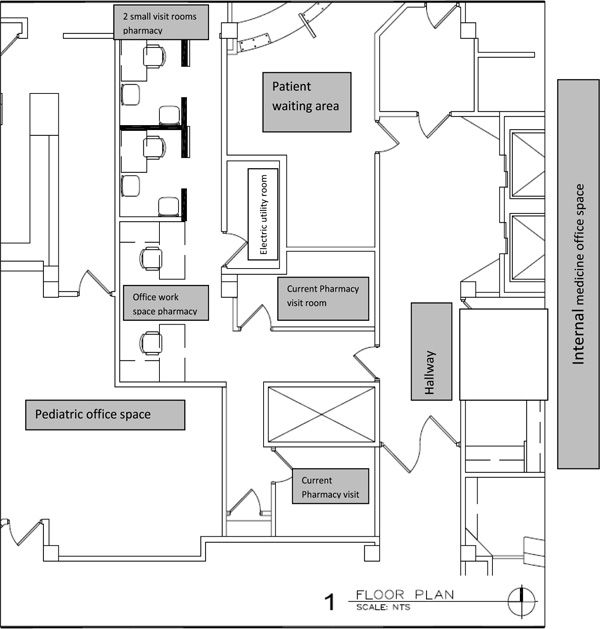

If the office and exam space that you are going to be using is already in an established physician’s office, the items noted in Table 5-1 (page 130) will already be in place. If it is not, work with the office manager to arrange the purchase of these supplies and add them to the existing space. If you are establishing your clinic in a new location or a community pharmacy, you will need to work with architects who may create blueprints of your exam room (see Figure 5-1 as an example). Be sure that your space is large enough to accommodate all needed equipment and supplies listed and that the entrance can accommodate a wheelchair. If you are lucky enough to be directly involved in creating your clinic space, be sure to consider the efficiency of your visits in terms of space. In a community pharmacy, you may want to consider when patients would see you in clinic, that is, before they pick up their prescriptions, while prescriptions are being filled, or afterward. Each time frame has its unique benefits: beforehand allows you to resolve any medication problems that may result in a change of medication before the filling process; during filling is efficient use of patient wait time; and afterward allows you to focus on tying filled medications to the education you are providing. Your decision will depend on the unique characteristics of your patient population and their needs, wants, or desires.

Figure 5-1. Blueprints of an Exam Room

Blueprint reproduced courtesy of Eckenhoff Saunders Architects, 700 S Clinton, Suite 200, Chicago, IL 60607. www.esadesign.com

Finally, if you are establishing a new service in a hospital-based clinic and space is going to be built for you, consider the location as it relates to the collaborating physicians’ group. If you wish to use incident-to billing for Medicare patients in a physician-based outpatient office setting, your space must be in the same suite or location as the supervising physician.7 The supervising health care provider (usually a physician, but it may also be a nurse practitioner or physician assistant) cannot be in a separate building. For more information refer to Chapter 8 for the rules for using this type of billing.

A requirement of using incident-to billing for Medicare patients is that auxiliary personnel, including pharmacists, must meet the direct supervision requirements. What defines direct supervision depends on where your service is located. If it is in a hospital-based outpatient practice, direct supervision is defined in the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (HOPPS).8 If it is in a physician-based outpatient clinic, what constitutes direct supervision is noted in the Federal Register.9 You cannot bill incident-to from within a community pharmacy setting unless a section of that setting is designated as provider office space where a recognized provider such as a physician, nurse practitioner, physician’s assistant, or any other professional designated as an independent practitioner by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) sees patients and your service provides care “incident-to” this practitioner.

Most third-party payers follow CMS guidelines. In those areas of the country where Medicare Part D plans, Medicaid, or other payers allow you to bill as a pharmacist provider using MTM CPT codes or other qualified codes, be sure to check for any specific supervision or space requirements in the particular rules and regulations.

Additional office space considerations may also include a receptionist area for check-in and check-out and waiting room space.

Once office space has been addressed, consider what additional supplies you may need (Table 5-1). This may include office items such as a desktop or laptop computer, phone, and a file cabinet to store patient education material and paper, pens, and notepads. Consider if any additional physical exam equipment may be needed, such as a pulse oximeter; monofilament; peak flow meter; tape measure; pill boxes and point-of-care (POC) laboratory testing devices for assessing PT/INR, blood glucose levels, or fasting lipid profiles. In some cases, the POC device cartridges must be kept in a refrigerator that is separated from an employee refrigerator and maintained in the clinical area. A temperature log of the refrigerator needs to be maintained according to the requirements of the College of American Pathologist laboratory guidelines.10 Many of these decisions are based on the type of clinic and service you will be providing. The key is to anticipate your needs ahead of time and plan for procurement, storage, and disposal (needle containers) of your needed supplies.

Clinic Scheduling Processes

Set up a patient scheduling system that is managed by clerical staff who directly schedule patients. The most important rule to remember when setting up your space is integrate, integrate, integrate.3–5 Often when starting a new service, clinical pharmacists do not wish to disturb the harmony of work flow by adding additional work for other staff. However, the more clerical work you take on, the more inefficient your service will be, and thus revenue generation potential will be impacted. The support staff is there so you can be productive. It is highly recommended that you set up your practice from the beginning using the model that meets your long-term needs.

| Table 5-1. Essential Items Every Space Will Need | |

| 1. | Chairs with durable vinyl coverings (not cloth due to difficulty in cleaning) and armrests for ease of getting into and out of the chair. Depending on your patient population, consider purchasing bariatric chairs that accommodate larger body weights. Consider obtaining at least two chairs, one for the patient and one for a friend, significant other, or child. |

| 2. | Exam room table with paper table covers if a physical exam will be part of the visits. Consider whether the table will need to rise and lower based on the age and dexterity of your patient population. |

| 3. | Desk or countertop to set chart or computer on during visits. |

| 4. | Desk chair or stool for clinician to use during visit. |

| 5. | Wall-mounted or portable sphygmomanometer with appropriate-size blood pressure cuffs (based on population of patients—pediatric, adult, large adults). Based on the service provided, you may consider obtaining an otoscope, ophthalmoscope, and thermometer to be added to the wall mount or in a portable basket. |

| 6. | Other equipment such as weight scales, microfilament probes, measuring tapes, and thermometer (see Chapter 2). |

| 7. | Clock with second hand for monitoring patients’ heart rate. |

| 8. | Latex-free exam gloves in multiple sizes. |

| 9. | Wall-mounted shelf to place educational materials. |

| 10. | Sharps containers if you are performing any lab draws, point-of-care testing, or injecting medication (immunizations for example). |

| 11. | Hand soap if the space has a sink. A hand sanitizer dispenser may also be considered. |

| 12. | With regard to technology, if using an electronic medical record or other electronic documentation system, you will need to assess how many computers are preferred. In addition, if patient documents or educational material will be printed, consider whether multiple printers are needed or if a network printer is a more suitable option. |

| Integration is the key to getting your practice up and running quickly and efficiently. |

CASE

It is fortunate that you are entering an office space already set up for patient care. The next step is to prepare the exam rooms, and you ask that the exam room used for anticoagulation management be rearranged so that it includes a work surface for the INR machine as well as supplies for finger pricks. You request that lancets, alcohol pads, gauze squares, and adhesive bandages all be assembled in a small tote basket for easy access. You also realize you will need to have access to the office’s electronic medical record (EMR), so you can request a laptop from the office supply and spend time setting up the electronic documentation templates to ensure each visit will flow smoothly and work within the current office documentation system.

A common mistake is for pharmacists to assume all the clerical responsibilities in the beginning because their office hours are not fully booked. However, once established, you will thus continue to schedule patients, pull your own charts, and perform your own vitals. It is highly unlikely the support staff will ever take on these responsibilities in the future. A major premise of health care reform and the new models of care are for all health care providers, including pharmacists, to spend the majority of their time practicing at the top of their skill level. Doing so will greatly contribute to a more cost-effective health care system.

| Clinical pharmacists should engage primarily in tasks commensurate with their skills in direct patient care. |

Integrating your service into the norm of clinic flow brings overall efficiency to the clinic as well. Oftentimes, each clinician’s schedule is reviewed electronically or printed as part of the process used to determine the workload for the support staff, including nurses, medical assistants, and technicians. Clinicians’ schedules are also reviewed to assist in managing patients who no-show for appointments.

In order for the office manager or assistant to begin developing your schedule, also known as “building your books,” he or she will need to know what days you wish to see patients, what times each day you are available, how long each new patient visit should last, how many new patient visit slots you want available per day, and how long follow-up visits will be on average.11 If you are developing a service that involves significant time spent identifying patient barriers to compliance and encouraging lifestyle modifications such as conducting cardiovascular risk reduction clinics (CVRRC), or managing diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or asthma, it is recommended that 45–60 minutes be allowed for new patient visits and 30 minutes for follow-up visits as a starting point.12–14 You may need to adjust the time in the future depending on the clinic or patient nuances.

CASE

In Dr. Busybee’s clinic, your service would be open for patient visits all day Wednesdays. To be patient centered, you build flexibility into your schedule, with new patient appointments designed for 30-minute slots and 20 minutes for follow-up appointments. You set a maximum of 12 patient visits for days in clinic. You build in 20-minute slots around patient visits to use for any needed post-visit work, phone calls, and documentation.

To embrace the patient centeredness of the new care models, it is best to be as flexible as permitted by the nuances of your organization. More progressive practice management systems permit you to define the parameters in general terms, thus offering more flexibility. If you are developing a new service that is medication-monitoring focused, such as an anticoagulation clinic, chronic pain management service, or GI management for patients receiving chemotherapy, maintain new patient visits at 45–60 minutes and have follow-up visits at 15–20 minutes. Remember to focus your services on the best balance between best care and efficiency to maximize patient outcomes and the reimbursement potential.

Billing Processes

If you are billing incident-to and would like to keep track of your workload, patient diagnoses, and revenue of your service, have the billing department assign you an internal provider number. This internal provider number is often called a performing provider number (PPN) and is an efficient option for assessing what the ancillary staff is engaged in. The PPN is not a billable provider number; however, it can be placed on a charge document along with a billing provider number (BPN). The BPN is assigned only to providers who have been authorized to bill a given payer. Thus, if you are billing incident-to a physician, you may note a PPN and BPN on the charge document. If you are a recognized provider for only one payer, for instance, for Medicaid, then you would use your assigned BPN on the charge document when seeing these patients, and for other patients you would use your assigned PPN along with another clinician’s BPN on the charge document. The PPN could be designated as your national provider identifier (NPI), but more often than not it is just an in-house number that is provided by the billing department.15 See Chapter 8 for details regarding NPI and which provider’s BPN to place on your charge document when billing incident-to a physician.

Referral Process

The next step is to develop a referral process for your new service. Considerations include which providers are permitted to refer patients to your service, if patients may self-refer, how the referral will be made (i.e., electronically entered by the provider, handwritten/faxed order in the provider progress note to be followed up by support staff to complete a referral form, or handwritten/faxed referral form completed by provider), and once the referral form is completed, who is responsible for actually scheduling the patient into your office hours. These referral forms should be kept for reasons discussed in greater detail later in this chapter. It is best that you implement the same referral process that already exists within the practice setting. If the physician practice group uses an electronic referral system, then have your clinic name added to the list of profile options, which means your service name will appear under the same consult tab where all other consult options appear. In such a scenario, typically a customizable referral form is available. (Referral Form Example) ![]()

If a paper referral process exists for other services, then try to adopt this same form as it will be challenging for providers to remember to use a unique pharmacy referral form. Disadvantages of developing a new referral form include educating all staff on how to complete a new form, noting that it is located in a spot different from the regular referral forms, and keeping this special form stocked in all exam rooms (or central area). The goal is to integrate all your processes into the existing clinic processes.

Follow-up Process

Two other processes that need to be developed involve managing urgent patient care issues that arise in your clinic and implementing follow-up for consultations that you initiate with other services. Many times an urgent patient care issue is discovered for which you need a supervising physician to evaluate the patient immediately, later the same day, or the next day. If there is no existing protocol, invite key stakeholders such as the office manager or nursing and clerical staff to provide recommendations regarding how to best manage this situation. Similarly, invite such staff to educate you about the process to address consultations, as permitted, to other services. For example, if you are seeing a patient in your diabetes clinic and your collaborative drug therapy management protocol permits delegated authority to write orders for consultations, you could send this patient to ophthalmology, podiatry, social work, or dietary services, as appropriate. The existing staff will be instrumental in helping you navigate the consulting process in your practice setting.

Access to Patient Information

If your practice site is in a community pharmacy, then you will likely need to develop a new process or obtain access to the providers’ EMR, or at a minimum, acquire basic medical information to perform your services. Currently under development nationally is the certification for the functionality of developing a pharmacy/pharmacist-EMR (PP-EMR). This would permit bidirectional electronic communication with clinic practice sites whose EMRs recognize the PP-EMR. Additional information regarding PP-EMRs can be found at the Pharmacy e-HIT Collaborative web site (www.PharmacyE-HIT.org). Another option is to request virtual private network (VPN) access to each providers’ EMR for which you have established a collaborative practice agreement. VPN connectivity permits remote users access to local networks. This is a routine, well-established practice that practitioners implement to access their own EMRs from home, and with proper security you can be given access to the patient medical records. This would permit you to directly access progress notes and lab results as well as to add your progress note into the EMR. This is an exciting prospect that decreases faxing notes and lab results to the physician’s office. This also helps resolve the problem of pharmacists’ progress notes sent via fax or mail not making it into the patient’s medical record. To be fair, some physicians’ offices are able to keep track of loose filing and to scan all records so that there is an electronic copy; however, it is not uncommon to see a stack of documents pending scanning in an office, which means there could be a delay with your documentation being signed off and placed in the EMR. This could lead to a host of problems, with the most evident being oversight in patient care. If communication via fax is your best option, then consider developing a fax form that is well organized and stands out as a progress note. ![]()

CASE

Dr. Busybee completes documentation for each patient visit within the practice’s EMR in which special templates were created and added for a pharmacy visit. Dr. Busybee and you worked with the IT department to facilitate this process prior to seeing patients. Once you complete your documentation, your SOAP note is sent electronically to Dr. Busybee for review and sign off. You are aware that in your home state it is required that referring physicians sign off on every note within 48 hours of the time you saw the patient, so you complete your documentation after each visit to minimize any delays in the process.

Clinic Work Flow Processes

Another task to consider when addressing clinic operations is clinic work flow.3 Clinic work flow involves all processes of how the patient moves through your service from first entering the building to leaving it. This process ideally would appear seamless to the patient. The patient at no time should backtrack through the space or have the opportunity to get lost. If the service is in a physician’s office, work flow should mimic that of the other providers by using the same clinic staff as the referring and ordering providers. If it is in a community pharmacy setting, new processes may need to be developed. Considerations include the following.

Patient check in. Who will check in your patients? What paperwork (if any) is printed and where is it placed? Where will the patients be waiting (general waiting room or a special designated area)? Standard paperwork usually given to patients when they check in includes the demographics form that patients review to ensure the clinic has the proper address and insurance information for billing, the HIPAA form that indicates what information the patient authorizes you to share and with whom, and possibly a consent form to participate in a collaborative practice agreement with a pharmacist and physician. The latter is required by some state laws, so check your state to see if the patient has to sign a contract/agreement in order to participate in clinical pharmacy services. (Other forms that may be given to the patient include a medication list to verify and an initial medical assessment form.)

| Clinic work flow involves all processes regarding how the patient moves through your service from first entering the building to leaving it and should appear seamless to the patient. |

Vital signs. Who will do vital signs—you or medical assistant or LPN? How will staff be notified that patients have arrived? Where will the vital signs be

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree