HOW A CLINICAL STRATEGY AND DEVELOPMENT PLAN ARE INFLUENCED BY THE QUESTION POSED

Nine Primary Questions

A drug developer could ask any of the following nine (or other) questions once a drug is ready to be studied in humans, assuming that a variety of disease states and approaches are possible to evaluate, and various clinical and regulatory strategies are being considered. These are framed as if the author of the clinical strategy is considering different goals of the program and has to decide which one or ones are the most critical to address in the strategy that is created and how they should be prioritized.

Q1: How can the company most clearly demonstrate that their new drug has a positive benefit-to-risk ratio in patients?

Q2: How can the company demonstrate that this new drug is as good as Drug X?

Q3: How can the company most clearly demonstrate that this new drug is better than Drug Y in safety and/or efficacy?

Q4: How can the company conduct clinical trials at a higher scientific standard than their competition, and thereby encourage regulatory agencies to require the other companies to redesign their trials at the new higher standard?

Q5: How can the company obtain “orphan drug status” and prevent other competing (identical) drugs from being marketed?

Q6: How can the company submit regulatory dossiers worldwide on a nearly simultaneous basis?

Q7: How can the company achieve regulatory approvals worldwide as rapidly as possible?

Q8: How can the company get its product to market most rapidly, both globally and in any particular developed country?

Q9: How can the company maximize the commercial returns from this product most rapidly?

While most of these nine questions could be answered similarly or even identically in some cases, the differences among the questions are likely to influence how the clinical strategy is designed and how the development program is set up and even where some or many of the trials are conducted. Although only nine questions are listed, the number posed could be far greater. When all other factors and issues relating to the clinical program, but not covered by these questions, are included (e.g., see

Table 60.1 and the following sections), the complexity and multitude of questions become obvious.

Therefore, the point of creating and asking the best questions should be understood as a critical step in creating the best clinical strategy and development plan.

Some of the implications of the nine questions are indicated in the following text as each is elucidated a bit more to illustrate the types of strategies that would evolve from posing that particular question. The questions and issues that need to be addressed for each of the nine prototype questions include the following: Should the strategy target a disease or more than one disease to evaluate where there is/are the (a) most patients, (b) greatest commercial value, (c) highest medical value, (d) least competition, (e) best proprietary position, (f) best growth potential, (g) greatest regulatory interest (e.g., due to the greatest public health need), or (h) most public relations potential? Since many companies would say “all of the above,” a better question is to ask how the strategy should prioritize these items. While some companies create strategic plans that focus on a company’s existing portfolio and/or in-house therapeutic expertise, others might focus on their sales force’s capabilities.

After the initial question is asked, a few additional issues and questions that could be raised and discussed are mentioned below. These are mentioned to indicate some of the directions that the questions could lead and differences in the protocols that would eventually be designed to answer the questions (and hypotheses) posed.

Question 1: How can the company most clearly demonstrate that their new drug has a positive benefit-to-risk ratio in patients?

If one literally answers this question, it would suggest that a surrogate endpoint not be used, because the most clear demonstration of efficacy and safety means that the most relevant clinical endpoints are to be chosen for evaluation. In addition, the company cannot skimp on the number of patients to be included in the development plan since the amount of risk information is directly related to the number of patients studied. Moreover, the trial designs chosen must be at the highest standards possible.

Question 2: How can the company demonstrate that this new drug is as good as Drug X?

The strategy could focus on showing that the new drug is as good in terms of safety, efficacy, convenience or other characteristics? Is the market leader really the best available therapy to use as a head-to-head comparator in clinical trials because it is the drug everyone will use as a comparison and works very well? One could decide to compare the company’s drug with an older drug that causes more adverse events or has other problems and leave comparisons with Drug X to Phase 4 or possibly for others to test?

Question 3: How can the company most clearly demonstrate that this new drug is better than Drug Y in safety and/or efficacy?

What advantages of the new drug should be highlighted versus Drug Y? Since the focus is on both safety and efficacy, it will influence how the trials are designed. We need to ask if Drug Y is the best drug to choose as a comparator agent? Is this the control drug that marketing wants research and development to use, and if so, why? Will the data convince physicians or will they see Drug Y as one of the poorest drugs used to treat the disease? Alternatively, is Drug Y the best drug available and is the company seeking to demonstrate that its new drug possesses significant medical advantages? In the past, some companies have picked a comparator drug they knew would cause many adverse events in order to make their own drug look better.

Question 4: How can the company conduct clinical trials at a higher scientific standard than the competition, and thereby encourage regulatory agencies to require the other companies to redesign their trials at the new higher standard?

This strategy was used with great success by the Burroughs Wellcome Company in the 1980s and 1990s in developing its neuromuscular blocking agents and surfactant to treat respiratory

distress syndrome. While it is not applicable (as a strategy) for all cases, it could be considered if there are competitors with similar or even identical drugs that are ahead or at the same state of development as the company. While this strategy can be attempted at any time, it is particularly effective if the company is first in a new indication.

High-quality research design may produce better quality data and increase the likelihood of success by reducing the possibility of a false positive or negative result. False positive data leads to further investment in a losing project, whereas a false negative result may lead to cancellation of a worthwhile drug.

Question 5: How can the company obtain “orphan drug status” and prevent other competing (identical) drugs from being marketed?

While this question pre-supposes that an orphan drug is being developed, there is sometimes a race among those with an orphan drug designation to obtain approval for marketing in order to prevent the competitors from reaching the market first and thereby blocking ones own product. The strategic implications of this competition are quite clear indeed.

Question 6: How can the company submit regulatory dossiers worldwide on a nearly simultaneous basis?

What approaches to clinical development will be viewed most favorably by the regulatory authorities? What disease treatment is likely to appeal most to regulatory authorities? Can we meet with them to discuss our plans? Will they tend to approve marketing applications for two (or more) indications simultaneously or only sequentially? Will they tend to approve marketing applications for two (or more) dosage forms simultaneously or only sequentially? Do we have the resources to attempt this goal, how many staff are required for this strategy, and what is the cost? What pharmacoeconomic and quality-oflife studies will we need to conduct to achieve this goal and have the level of reimbursement we seek and the placement of the drug on all relevant formularies?

Question 7: How can the company achieve regulatory approvals worldwide as rapidly as possible?

What diseases can be studied most easily in the various countries that are of greatest marketing interest? Should we choose only one disease to study worldwide and one dosage form of the drug or can we study a different disease and dosage form in each country? What are the biases of medical practice in each of those countries toward certain dosage forms and certain disease diagnoses for which the drug could be used? How will these influence the strategy we adopt?

For both questions 6 and 7, do we have the resources to attempt to collect data internationally to achieve this goal? Do we believe this project warrants the priority (and resources) that would be necessary to achieve this goal? What other projects, if any, would suffer by making this project a high priority? Should we seek a corporate partner to achieve this goal?

Question 8: How can the company get its product to market most rapidly, both globally and in any particular developed country?

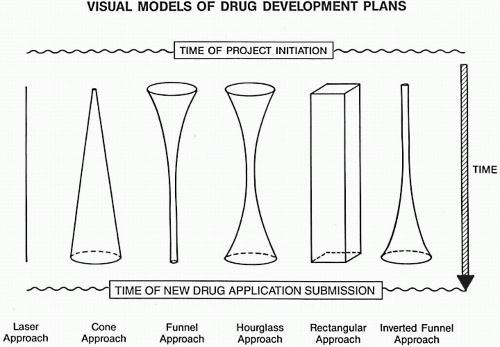

This goal allows one to focus the strategy on a single country and to see which studies are “nice to have” but are not absolutely required for a marketing submission. A laser-like visual model (described later in this chapter) would be desirable to achieve this goal.

Question 9: How can the company maximize the commercial returns from this product most rapidly?

The answer to this question is quite straightforward. Develop the indication with the highest commercial value and focus the company’s efforts on that indication. Do not get sidetracked with other indications, dosage forms, and routes of administration. Even when no problems are anticipated in developing additional indications and in the planning and conduct of the necessary additional trials, such diversions often raise problems that no one anticipated and take a great deal of time to address. Mr. Murphy has created several laws that relate to this decision. This basic question also needs to consider which clinical trials marketing believes it must have prior to its initial launch.

In reality, many, if not most, of these nine questions (and many of the subsequent questions) would be asked regardless of which question was initially posed. Nonetheless, the order in which the questions are asked, as well as the importance given to each of them, could be vital in determining the strategic direction taken in developing the drug. Sometimes, even factors such as a physician friend of the head of research and development or an academic acquaintance of the President encouraging a certain approach have had a major influence on the initial direction pursued (the author has unfortunately seen both of these events occur in the largest pharmaceutical companies).