Conflicts of Interest and Bias

Conflicts of interest are ubiquitous and inevitable in academic life, indeed in all professional life. The challenge for academic medicine is not to eradicate them, which is fanciful and would be inimical to public policy goals, but to recognize and manage them sensibly and effectively.

–David Korn. From the Journal of the American Medical Association (2000).

This chapter discusses conflicts of interest and bias from a pharmaceutical company perspective, but also describes the issues as they exist in both academia and government. It describes many of the situations in which conflict of interest and bias can arise and suggests principles that should be used to guide behavior in response to these situations.

DEFINITIONS AND DESCRIPTIONS OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST AND BIAS

A conflict of interest can be defined as a situation in which one’s self-interests are in potential conflict with the interests of another person or company with which they work (i.e., one’s loyalties are

divided). Alternatively, one’s responsibilities to two (or more) external groups are in conflict. From the perspective of a pharmaceutical company, conflict of interest arises when an individual’s ability to fulfill his or her professional responsibilities in an unbiased and objective way is impaired or could be impaired by that person’s involvement or interest in the outcome of the activity. A conflict of interest may arise through financial interests of the person or the company, ethical beliefs, religious beliefs, a relationship through blood, or on another basis. A conflict of interest often occurs when a person could create an unfair competitive advantage for himself or herself, others, or an organization (e.g., company). The conflict may actually exist, or it may only have the potential to exist. Even when an actual conflict of interest clearly exists, that person’s behavior will not necessarily be influenced. Moreover, situations that appear to one person or organization to be a definite conflict of interest may not appear to be a conflict to another. For example, an academic investigator who establishes a professional relationship with a company may be viewed as having a conflict of interest by some, but this relationship might be a mutually beneficial working one.

divided). Alternatively, one’s responsibilities to two (or more) external groups are in conflict. From the perspective of a pharmaceutical company, conflict of interest arises when an individual’s ability to fulfill his or her professional responsibilities in an unbiased and objective way is impaired or could be impaired by that person’s involvement or interest in the outcome of the activity. A conflict of interest may arise through financial interests of the person or the company, ethical beliefs, religious beliefs, a relationship through blood, or on another basis. A conflict of interest often occurs when a person could create an unfair competitive advantage for himself or herself, others, or an organization (e.g., company). The conflict may actually exist, or it may only have the potential to exist. Even when an actual conflict of interest clearly exists, that person’s behavior will not necessarily be influenced. Moreover, situations that appear to one person or organization to be a definite conflict of interest may not appear to be a conflict to another. For example, an academic investigator who establishes a professional relationship with a company may be viewed as having a conflict of interest by some, but this relationship might be a mutually beneficial working one.

Conflicts of interest can be found in so many situations that if one actually looked for and enumerated them, most would cease to have almost any significance. It is the author’s belief that every professional has them. For example, a physician who wants to earn money, avoid committing malpractice, and spend time on personal activities while being available to treat his or her patients could do almost nothing that would be 100% free of possible accusations of conflict of interest. But there are standards of behavior for professionals within each culture that are widely accepted. Some of these are codified as principles of medical ethics or principles of specific societies. Certain behaviors are agreed to be below universally accepted ethical standards in all developed countries (e.g., accepting bribes, providing secret kickbacks of money for services provided), although one hears frequent reports of their occurrence.

Does Conflict of Interest Lead to Bias?

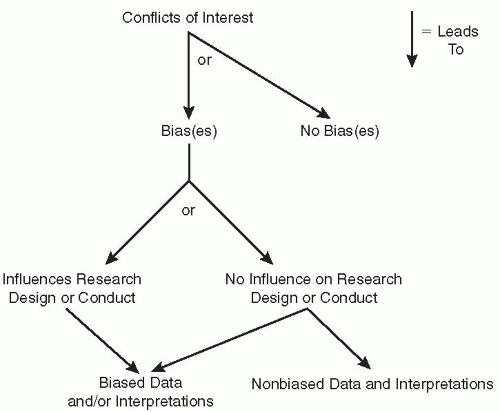

The media and scientific journals base many of their stories on the assumption that conflicts of interest need to be prevented and only those individuals who do not have the obvious types of conflict of interest should be able to serve on government panels [e.g., Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Advisory Committees] or conduct intramural research for the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The author believes that almost all of these discussions miss the major point: Are these conflicts of interest influencing the results of research experiments, clinical trials, or the voting FDA Advisory Committee members? The author’s point is that conflict of interest does not equal bias and does not necessarily lead to bias. Even when conflict of interest does lead to bias the question remains: Did the bias influence the decision that was made, or influence the design or conduct of the research experiment or study? If so, there will be biased data or interpretations. Even if the bias does not influence the research design or conduct of an experiment, bias may influence the interpretation of the data obtained (Fig. 25.1).

Does a Biased Scientist or Physician Always Produce Biased Results?

Academic investigators who conduct research using their own money or monies from non-industry sources may or may not have strong biases about the results they hope to obtain, based on supporting their theories or previous work. If they do, then there is more opportunity for the data to somehow come out the way they hoped. On the other hand, if an investigator has strong biases, it does not mean that they have influenced the trial in any way because many biased investigators are objective and honest about their research and its interpretations. Therefore, both biased and nonbiased investigators may have complete integrity.

The goal of achieving objective science and scientific discussions is not to try to remove conflicts of interest or even bias per se, but to prevent biases from influencing both preclinical and clinical research results. Even if professionals are chosen for FDA Advisory Committees who have no conflicts of interest, they still have personal biases and these have the potential for leading to biased results of their discussions.

Safeguards against Bias Influencing Results

The example used is a clinical trial. Some of these and other safeguards exist for preclinical studies. These safeguards include:

FDA rules on financial disclosure

Journal rules on financial disclosure and also on conflicts of interest

NIH and government agency rules on financial disclosure

Protocol reviews by the sponsor, investigator, clinical research unit, Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), FDA, and sometimes the institution or a department therein

Audits by the sponsor or others

Peer review process in publishing and presenting required elements of a trial on websites prior to initiating them

Encouraging higher standards for protocol design (e.g., well-controlled, double-blind, adequate number of patients)

Types of Conflicts of Interest

While the media, public, journal editors, FDA, and NIH focus most clearly on financial conflicts of interest, there are other types of conflicts of interest that are often more important to academicians and government scientists. Some of these have financial consequences, either directly or indirectly. These include:

Academic advancement

Administrative advancement

Attaining tenure

Achieving prestige and fame in one’s profession

Winning grants

Obtaining additional power in one’s institution

Obtaining the ability to expand one’s research activities through additional staff or labs

Conflicts of interest may be categorized into four groups:

Real but unknown to the individuals involved. For example, a person may be studying or testing a product from a company that licensed it from another company in which that person owns stock. This raises the question of whether someone must be aware of a situation for it to be a conflict of interest.

Real and known to the individuals involved. For example, a person owns a major amount of stock in a company whose product he or she is testing or studying.

Potential conflicts of interest. No conflict exists until certain events occur, which may or may not be outside that person’s control. For example:

A person purchases stock in a company after he begins testing a product, but well before results of his tests are known.

A scientist’s child marries someone who is an officer in the company that owns the product they are testing.

A person is offered stock or other financial incentives by a company after that person becomes involved in testing the company’s product.

A person engages in certain activities approved or requested by his company. For example, a senior scientist at Merck, Dr. William Abrams, went to the FDA in Washington, DC, on a part-time basis to help establish the FDA‘s training and education program. Several people in government and at Merck realized that some of his activities could potentially lead to a conflict of interest (Dr. William Abrams, personal communication). This possible conflict of interest was avoided by a memo of understanding drawn up in advance by attorneys for the FDA and Merck. This agreement specified some topics on which he could work and other activities that he would avoid, both at Merck and the FDA, during his period at the FDA. Thus, conflict of interest was avoided.

Perceived by others but not currently perceived as a conflict by the person “involved.” Perceptions of conflict of interest by others often make a conflict real, even though it may not be true.

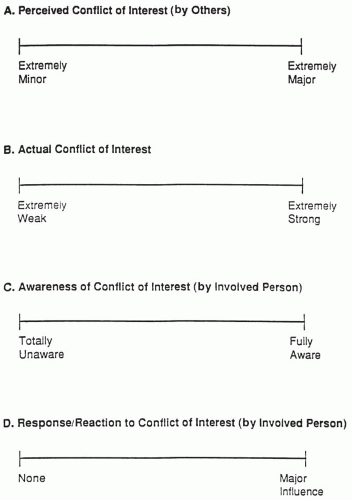

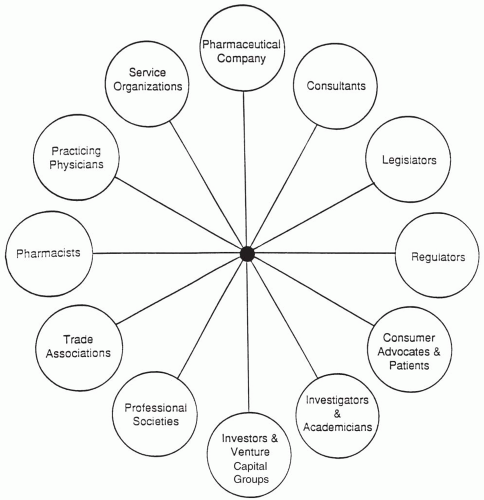

A summary of the definitions and the spectra described in this section are summarized in Fig. 25.2. The major groups involved

in conflicts of interest in the pharmaceutical industry are indicated in Fig. 25.3. Any two groups potentially could be involved, although this chapter primarily focuses on situations in which one group is a pharmaceutical company.

in conflicts of interest in the pharmaceutical industry are indicated in Fig. 25.3. Any two groups potentially could be involved, although this chapter primarily focuses on situations in which one group is a pharmaceutical company.

Institutional Conflicts of Interest

It is not only individuals that have conflicts of interest, as it is very obvious in almost all journals and media that institutions also have conflicts of interest. These include issues related to:

Fame and glory for the academic institution, pharmaceutical company, or government agency

Desire for more research grants for the institution. This is usually an academic one. For example, there are annual lists of which academic institutions receive the most government grants and other such rankings.

Desire to attract the top scientists and students to their institution or pharmaceutical company

Desire for the most important publications. Awards are often given based on such competitions.

Desire for royalties from licenses to academic patents and products. The number of technology transfer offices has grown rapidly over the past ten or so years. Some academic institutions are screening compounds via high throughput screening programs seeking useful biologically active compounds to license out.

Desire for increasing the value of the stock they own (e.g., in endowments and pension funds) in various healthcare and other companies

FACTORS THAT CREATE CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The most common factor that creates conflicts of interest is financial gain. Financial gain may be in the form of money, stocks, stock options, royalties, or other economic benefits (Table 25.1). The gain may be immediate or delayed, but the possibility of financial benefit is the factor that has influenced the person affected.

Table 25.1 Selected examples of financial relationships between an individual outside a company and the company itself that may create a conflict of interesta | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

Money is not the only major influence that often leads to or creates conflicts of interest. Other factors include the desire of the person influenced for (a) career growth, (b) recognition and prestige, (c) increased power within a group or organization, (d) maintaining (i.e., not losing) one’s current job or position, and (e) obtaining sexual favors. While these factors are nonfinancial, a few (e.g., career growth, increasing power) may lead to improved economic status. Nonetheless, money is not the primary reason that the specific factor has created a conflict of interest.

Conflicts of interest arise for either passive or active reasons. Passive reasons are those that the person has little or no control over (e.g., blood relationships) prior to becoming involved in a specific situation in which conflict of interest arises. Active reasons are those created by the person himself or herself (e.g., purchases stock), either prior to or subsequent to the situation or event in which the conflict of interest arises.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree