Chapter Outline

| Web Toolkit available at www.ashp.org/ambulatorypractice |

Chapter Objectives

1. Identify the relevance for pharmacists’ documentation of clinical services.

2. Compare and contrast manual and electronic documentation systems.

3. Review the common documentation styles and communication techniques used in clinical practice.

4. Recognize the appropriate levels for billing based on an example of documentation.

5. Discuss continuous quality assurance and other safety measures when implementing and maintaining documentation.

Introduction

Regardless of your practice environment, you will need to use electronic and manual methods of documentation to communicate, exchange information, and educate patients, caregivers, and other health care professionals. Like other health care providers, you will primarily use the patient medical record (PMR) for documentation of patient care. Through efficient and comprehensive documentation you can (1) meet professional standards and legal requirements, (2) communicate with other health care professionals, (3) establish accountability for medication-related aspects of direct patient care, (4) strengthen transition and continuity of care, (5) create your record of critical thinking and judgment, (6) provide evidence of your value and workload allocation, (7) justify reimbursement for cognitive services, and (8) provide needed data for tracking of patient health outcomes.1

Currently, industry-driven advances in technology are having a profound effect on how pharmacists document and are also creating new challenges. With the passage by Congress of the stimulus package (the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, or ARRA), expansion of health information technology (HITCH) is now mandated by the U.S. government. ARRA budgeted approximately $150 billion for health care reform and close to $34 billion for health care provider adoption of HITCH and a nationwide health record system by 2014.2 The most critical element to the e-health system is the electronic medical record (EMR) and the electronic health record (EHR). An EMR is a portal that shares relevant patient information among health care professionals. Likewise, it can perform as a patient scheduler and an intraoffice messaging system as well as assist with laboratory communications, e-prescribing, and billing processing. An EHR is an individual patient medical record digitized from many locations or sources, including the patient and family members. It can interface with evidenced-based treatment algorithms and protocols, outcomes reporting, and quality assurance and is synonymous with what is also called the patient medical record (PMR). An electronic personal health record (ePHR) can be created by patients, physicians, pharmacies, health systems, and other sources, but originates from a patient.2

An EMR and EHR can enhance provider communication in all health care settings. EMRs are primarily focused on physician and hospital-based practice, but there is potential for benefit in pharmacy practice with wider implementation. EMR adoption is predicted to bring the following patient and health care provider benefits: lower costs, quality care, improved reimbursement, enhanced productivity, efficiency, effectiveness, and communication.2

While the EMR has promise of advancing patient care and can be a resource to capture patient encounters, it is not without its challenges. This is especially true in the primary care setting due to the sheer number and small size of ambulatory organizations. Pharmacists practicing in the ambulatory patient care arena have historically used a modified SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) note format to document patient encounters, with sections expanded or omitted based on relevance to the practice and scope or service. It has been physician, and not pharmacist, work flow that has driven creation, adoption, and integration of most outpatient EMR and PMR applications. Consequently, it has been difficult to alter or adapt a physician-driven EMR to fit the work-flow dynamics of a pharmacist-provided visit in the ambulatory setting. For example, most templates that fit individual disease states have predetermined signs and symptoms that are consistent with a pharmacist’s visit, such as documentation of hypo- or hyperglycemic symptoms for diabetes; however, pharmacists do not perform eye exams routinely, thus documenting a normal eye exam would be inappropriate in the template. This is where the EMR can be tricky for the pharmacist because both are normally included in a diabetes visit template. This is important since it relates to payment for clinical services. Although pharmacists do not perform detailed physical exams, we do address complexity, such as multiple disease states, some aspects of review of systems (ROSs) and physical exams (PEs), monitoring, follow-up, and capturing of outcomes. Documentation on templates is designed to emphasize and ensure that the appropriate information is in place for billing using the correct evaluation and management service codes. Using a template that has incomplete sections or that can be billed inappropriately (physician services versus a midlevel provider services) could result in devastating financial and legal consequences for your organization. Depending on your EMR, investigate whether it has the ability to code and recognize language used in your template to populate other fields in the PMR to ensure correct billing for your services, to collect data related to your services, and to generate a list of patients for whom you have provided care. If not, you should consider a separate clinical pharmacy documentation system to capture your needed documentation. Optimally it should integrate in some form or manner with your organization’s EMR.

CASE

In Dr. Busybee’s office they have already converted from a paper PMR to an EMR. Now that all the logistics of seeing patients in the office are resolved, you must determine how you want to document your interaction with each patient. After a review of the current EMR you noticed that none of the disease state templates address anticoagulation management; however, the good news is the diabetes management template used by the physicians could be used for your visits as well. Knowing that you have no built-in system to document care given for patients using an anticoagulant, you approach the office manager about changing the EMR. The office manager promptly tells you this is outside their expertise and that they want nothing to do with changing the EMR setup. Dr. Busybee really does not understand why you cannot just type your encounter note into the EMR. You attempt to explain the volume of patients and the time commitment for that type of documentation. His response is “We use the EMR in this office — make it work so I can start referring patients to you as soon as possible.”

Because EMRs generally are not created with clinical pharmacy practice in mind, you may have already concluded it will be important for you to collaborate with your institutional information technology (IT) personnel as well as pharmacy management system (PMS) vendors as needed to develop the necessary technical integration solutions that incorporate your work flow and corresponding documentation requirements.2 This seems like a straightforward solution; however, many IT personnel have no experience with pharmacists seeing patients in an ambulatory setting or with the details of how we document, so they may be unwilling or lack sufficient knowledge to build a special area for a pharmacy visit within the adopted EMR. This can be further complicated by the fact that not all EMRs are created equally, and the adopted EMR may require a major system overhaul or significant financial outlay to accommodate your clinical services. You should be prepared to educate IT personnel on how you document your patient encounters, such as the need for a universal template for all pharmacotherapy-based visits and specific disease-state templates (e.g., diabetes or anticoagulation). An existing physician template may be used with minor or no alterations.

How do you know which type of templates work for you within an EMR? Just like other challenges in the pharmacy world you will need to research and investigate the functionality of the proposed or current EMR at your site. Visit the EMR vendor web page and familiarize yourself with the advantages and disadvantages of the application and whether the system can address the needs of midlevel providers such as the clinical pharmacist. Reviewing articles and attending lecture series as well as professional meetings may help, but usually it requires your review of your particular system to solidify its application to your services. One resource is the American Medical Association’s online bookstore.3 Currently, there are several books available that discuss types of EMRs, as well as incorporation and maintenance of the systems. (AMA web site) ![]() Granted, pharmacists rarely have a vote in the decision regarding which system is purchased for outpatient services, but such EMR resources can educate you on which systems allow specialization and customization and which are more restrictive in adapting to midlevel provider patient care services.

Granted, pharmacists rarely have a vote in the decision regarding which system is purchased for outpatient services, but such EMR resources can educate you on which systems allow specialization and customization and which are more restrictive in adapting to midlevel provider patient care services.

Once you understand your EMR’s flexibility and how your services will integrate into the EMR system, you can begin to create or adapt your current manual patient care notes to an electronic template format. The majority of EMRs do use a SOAP-based format, but it may appear unrecognizable because many systems follow a point-and-click process rather than use free text for documenting. No matter which format, you will have to integrate your documentation within the systematic approach designed by the EMR’s manufacturer. It is imperative that your documentation work flow be developed with your input and feedback to ensure the documentation process is efficient, easy to use, synergistic with the flow of the patient visit, and captures all the needed information. If the process is not scrutinized thoroughly, you may find yourself inefficiently jumping around the screen or having to type a large amount within your template; this leads to less time spent seeing patients and ultimately decreasing productivity and reducing reimbursement, which affects the viability of your practice.

One solution is to critically assess work flow with IT assistance to create an electronic template that is geared toward practice functions (pre-visit information gathering, visit documentation, orders you are able to execute, and billing) as well as the type of patient care visits you encountered. One example is an anticoagulation visit in which the international normalized ratio (INR) is obtained by the nursing staff while they are doing vitals and preparing the patient room for the office visit. You may then enter the room to complete your visit with information already entered into the electronic note. Alternatively, you, a resident, or your advanced practice clerkship student could be responsible for performing vitals, point-of-care testing, and the interview. The work flow and thus the note would be different. The key is to create your template around the structure and flow of your patient visit. No matter which work flow and template is incorporated, your note should always contain the following elements:

- time of arrival and departure

- chief complaint

- history of present illness

- past medical history

- allergies

- social history

- family history

- appropriate referrals

- labs

- medication reconciliation

- assessment and plan

(Example Documentation Elements for EMR/PMR) ![]()

CASE

Over the past 3 months you have slowly integrated into Dr. Busybee’s practice, and your office hours have gained momentum to where you are seeing approximately 20 patients per week. Dr. Busybee calls you into his office to discuss how the first quarter has gone and wants to know if you are “keeping track” of your impact. After some thought, you admit the last 3 months have been busy and just keeping up with the clinical aspect of your job has taken a great deal of time. Dr. Busybee reminds you of your business plan proposal and would like you to create metrics and outcome measures to ensure you are meeting your goals. In the meantime he has been approached by a local pharmacy school and asked if his office would allow pharmacy students to complete an Ambulatory Care rotation. They are offering compensation for each student, and he believes this is a perfect fit since they have you in their practice. This allows for additional revenue to the office and helps pay your salary. You agree to act as a preceptor with the first student starting in 2 months. The first thought you have is: How will I integrate these students into my clinical practice site, how best can I utilize students to help me accomplish my work, and what hurdles do I face with documentation if I allow students to see my patients?

Once you have your work flow outlined and templates designed, the next step is to ensure the security of your system. The overall security will be created and implemented by the IT department; however if the setting is an experiential training site, you will need to create security measures that limit the access of your pharmacy students. For a thorough experience, students will need access to the EMR with their own log-on information; however, their integration must be limited so they cannot “complete” an encounter note without your preceptor’s electronic signature.

Another consideration is integrating pharmacy residents that are completing training at your institution into your documentation process. As pharmacy residents are licensed pharmacists and generally should receive greater autonomy, you may wish to create an electronic preceptor section within the encounter note that allows the preceptor to add addenda and cosign the resident’s completed note. This allows supervision by the preceptor, a level of autonomy for residents, and billing for the visit, since technically the precepting pharmacist is the collaborating midlevel provider, not the pharmacy resident.

Despite the many challenges, transitioning to an EMR and computerized provider order entry (CPOE) is the future and a requirement under new Medicare Part D regulations that were effective in 2009. Technological advancement certainly facilitates generation and transfer of documentation and holds much promise to improve patient safety, although many concerns still exist, such as access to data (storage) and patient confidentiality. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) has an investment to “increase the extent to which health systems apply technology effectively to improve the safety of medication use.” ASHP has identified several targets to aid in goal achievement, including enhanced use of CPOE and EMRs, along with enhancement of information access and communication across the health care continuum. Since 2005, pharmacists in 19% of health systems transfer information to promote seamless care of patients with complex medication regimens. ASHP strives to increase integration of technology as the new pharmacy practice model is defined and adopted by practice sites.2,4

Documentation Styles

Whether the information is typed or written into a PMR, the documentation of a clinical interview should provide (1) what happened, (2) to whom, (3) who made it happen or the cause of the event, (4) occurrence, (5) rationale for why it occurred, and (6) outcome of action.1,5–9 A survey among community-based pharmacists identified the following primary characteristics of ideal documentation practices: comprehensiveness, affordable cost, time efficiency, ease of use, and ability to generate patient reports.5 Additionally, with our improved understanding of the perils associated with patient transitions of care, communication and coordination of care documentation should be added to this list. Several documentation styles can and have been adapted to record pharmacist encounters, including unstructured notes, semistructured notes, and systematic records, all possible in written documentation and growing in popularity within EMR formats. No matter the format and media, documentation should be

The most common format used in the medical system is systematic documentation, which includes SOAP, TITRS (title, introduction, text, recommendation, signature), and FARM (findings, assessment, recommendations or resolutions, and management). Other examples of structured formats include drug-related problem, rationale, plan (DRP); data, assessment, and plan (DAP); and drug-related problem, data, assessment, and plan (DDAP). TITRS is an assessment approach, and FARM places importance on monitoring, but these formats are not common among pharmacists’ documentation and therefore are not discussed in greater detail. The SOAP note is an interventionist approach and considered the standard for most if not all health care providers, including pharmacists.1,6–8

Each style of structured or unstructured noting has advantages and disadvantages but should be consistently used in the most effective and efficient manner. Unstructured notes are seen more commonly with traditional manual documentation, and as the name implies, they are free in form, with appropriate language and chronology. Advantages of this style are that the notes can be written expeditiously while still providing a solid, high-quality, general overview. One disadvantage is the note may be incomplete and inconsistent, which limits communication to other health care professionals, leaving practitioners vulnerable to liability. This type of documentation, whether it be manual or electronic, is usually reserved for phone messages and informal communication between practitioners regarding ongoing patient care issues secondary to the limitations.1,6,7

To be more complete the majority of manual and electronic documentation follows the systematic approach, allowing for completeness, consistency, and organization. Without a systematic structure, the documentation of the encounter may be time consuming and confusing, especially in regards to the placement of information from different sources. An example of this can be seen when documenting height, weight, and allergies. One clinician may document this information in the subjective findings, and another may place the information within the objective data collection section. The primary determinant for where this information should appear is how the information was collected. Was the information patient reported (subjective) or clinician measured (objective)? This problem may not be as apparent with an electronic documentation since many of the templates allow data to be entered only in certain fields of the encounter note, creating semistructured documentation. This blends different styles for which some fields are more standardized and others are free text. Like unstructured documenting, semistructured documentation may also lack the quality and consistency of the standardized SOAP note. Semistructured noting may be best used when triaging or forming a general impression for referral with no specific action needed by the pharmacist, much like a phone message or reporting of a lab result to the collaborating practitioner.

The more structured SOAP note format is appropriate when follow-up and monitoring are required as well as showing continuity of care provided by the health care practitioner. Both of these documentation styles have been used routinely with written communication and now are slowly being integrated as standards for the majority of EMRs.1,6,7,10 This is especially true of the SOAP format since it is the primary form for which payers traditionally reimburse.

No matter the format or style, documentation should always be used to demonstrate the impact of your interventions to improve patient care and the overall management of the chronic disease state(s). In addition, the documentation needs to support and allow for reimbursement. All documentation should be complete, complementary, compelling due to supportive evidence, and standardized and systematic to complement the oral communication among providers. Furthermore, documentation should reflect patient agreement with the care plan among multiple providers in terms of medication reconciliation, data collection, continuity of care, and the transitioning of care along the continuum.1,6–8,11,12

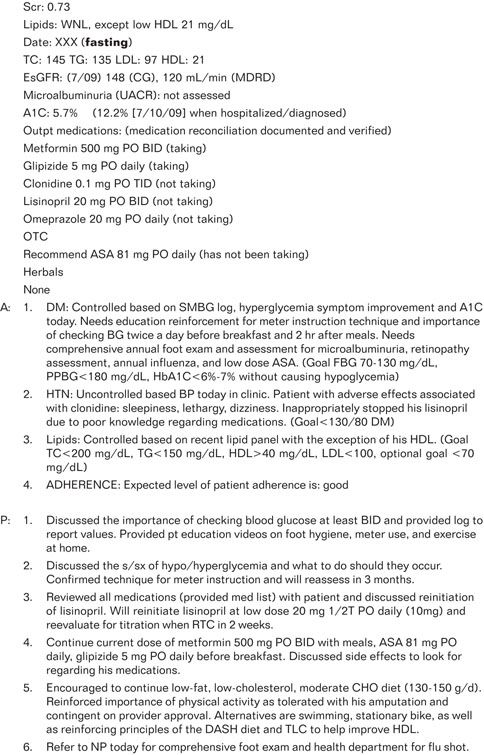

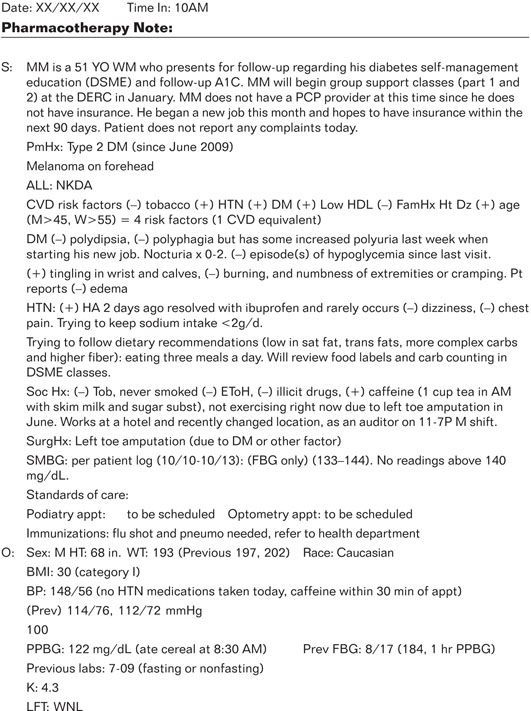

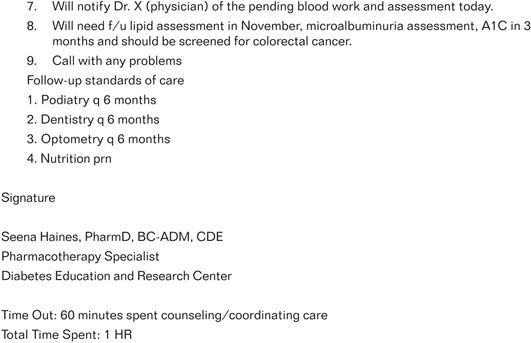

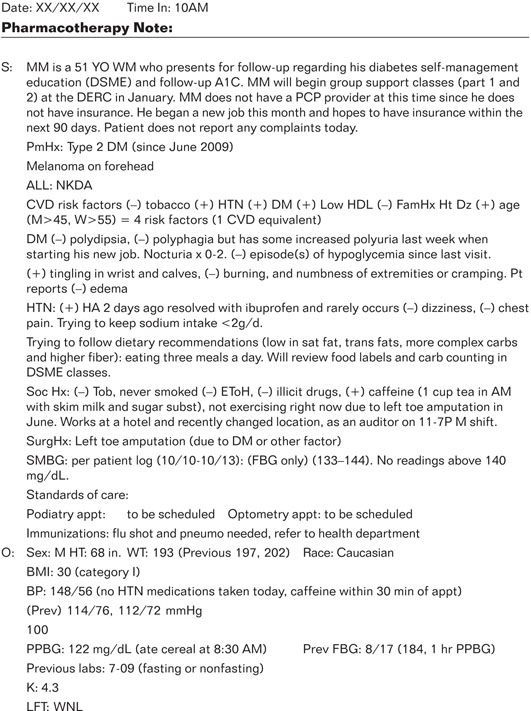

Knowing this makes it much more apparent that documentation is more than completing forms or capturing data during a patient encounter. No single ideal format can encompass all patient interviews, yet documentation can still provide evidence of the pharmacist’s interventions in advocacy and patient management. An example SOAP note (Figure 6-1) illustrates a standardized, structured approach to documentation and medication reconciliation, which will be discussed shortly. (Example SOAP Note) ![]()

The four distinctive sections of a SOAP note are outlined as follows:1,6–8

1. Subjective: symptoms, information, and answers to provider questions that the patient verbally expresses or that are provided by a caregiver. These descriptions provide a clinician with insight into the severity of a patient’s condition, the level of dysfunction, illness progression, and degree of pain.

2. Objective: measurements that are observed (seen, heard, touched, smelled) by clinician or that can be tested. Examples include vital signs, pulse, temperature, skin color, edema, and diagnostic testing.

3. Assessment: a prioritized list of assessed conditions. Simply stated, it is what you think are the patient’s issues or problems from your perspective as a pharmacist provider. This may consist of a level of control, differentials, potential confounders to control, pertinent positives or negative signs and symptoms related to the condition, reference to evidence-based medicine (EBM), considerations for pharmacotherapy, and adjunctive lifestyle measures.

4. Plan: care plan action steps for the patient and health care practitioners. The plan consists of the actions that you initiate or suggest to improve or resolve the issues or problems identified in the assessment. This may include requests for additional laboratory or diagnostic assessments, alterations in pharmacotherapy, lifestyle recommendations, standards of care, special directions, referrals, self-monitoring, emergency contacts, and time for follow-up appointments.

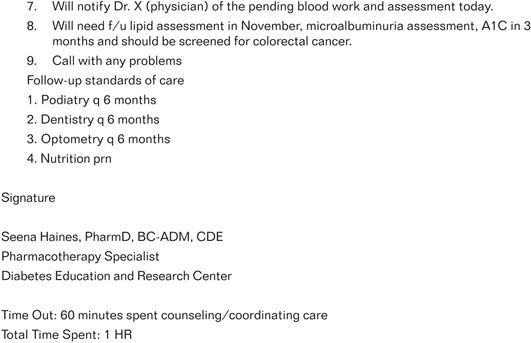

Figure 6-1. Example SOAP Note (written by SL Haines).

Additional considerations when documenting patient care can be obtained from the ASHP Guidelines on Documenting Pharmaceutical Care in Patient Medical Records, Guidelines on a Standardized Method for Pharmaceutical Care, and Table 6-1 provides other characteristics for documentation in an EMR/PMR.6,7

| Table 6-1. Example Items for Documentation in an EMR/PMR1,7,9 | |

| Chronological Marker | Date and Time |

| Summary of Medical History | CC (chief complaint) HPI (history present illness) PmHX (past medical history) SocHx (social history) FamHx (family history) SurgHx (surgical history) ALL (allergies/reaction) Medications/OTC/herbals PE/ROS (physical exam/review of systems) Laboratory indices/diagnostic procedures |

| Oral/Written Consultations | From other health care professionals (HCP) |

| Oral/Written Orders | From physician or other HCP – start and stop dates – precautions – drug interactions – protocols |

| Medication Changes | Adjustment of dose, route, frequency or form Intended use |

| Drug-related Problems | Actual and potential – drug-drug – drug-food – drug-lab – drug-disease |

| Assessment and Plan | Interventions and professional judgment |

| Therapeutic Monitoring | Rule out duplication Expected adherence Pharmacokinetics Adverse events/toxicity Clinical resolution/symptomatology |

| Patient Education | Therapy related Adjunctive measures Self-monitoring Etiology and progression of disease |

| Identifiers | Person(s) involved Documenting pharmacist |

| Aesthetics | Indelible ink Nonalterable (electronic) |

| Policies | Code of ethics HIPAA |

| Reimbursement | CPT codes: 0115T, 0116T, 0117T ICD-9 and Evaluation and Management (E/M) Time in and out, total time spent/rate of service E/M Medicare standards |

The SOAP note is an example from a patient-pharmacist diabetes self-management educational encounter in a specialized outpatient ambulatory multidisciplinary diabetes practice. The structured note lists the assessment and plan separately; alternatively, they may also be combined. Both are suitable forms of documentation for reimbursement, and the choice is left to clinician preference or documentation procedure unique to your individual practice site.

SOAP notes can be kept in a PMR for ease of documentation for follow-up visits or in a patient registry to expedite data collection and report clinical indicators. Alternative styles of structured notating can also be integrated with the use of an EMR through a variety of manufacturers as discussed.![]() These alternative styles are contingent on the care setting, funding support, your preferences and access, as well as the structure of your practice site. Some may have the ability to adopt pharmacy-based software for documentation, and others will use the software chosen by their practice site administrators and purchased by their health system. (Community-Based Clinical Pharmacy Documentation Software–Table)

These alternative styles are contingent on the care setting, funding support, your preferences and access, as well as the structure of your practice site. Some may have the ability to adopt pharmacy-based software for documentation, and others will use the software chosen by their practice site administrators and purchased by their health system. (Community-Based Clinical Pharmacy Documentation Software–Table) ![]()

Even as electronic information resources (EMR/EHR) gain momentum, it is apparent many practices will still rely on paper and pen for manual documentation. No matter the form, the same documentation principles apply, and the information contained in a PMR serves as justification for reimbursement, a legal permanent health record, and a quality-assurance tool for practice standards.1,7,8

Documentation Elements

Medication Therapy Management Community-Based Core Components

The ability to bill for pharmacist services took effect under medication therapy management (MTM) provision of Medicare Part D.13 A community-based MTM model was developed in July 2004 under the partnership of several pharmacy organizations and published through the American Pharmacists Association and National Association of Chain Drug Stores. Managed care health systems and payers have acknowledged that pharmacists provide consistent, cost-effective, clinical services that improve patient outcomes and reduce health care expenditures.14–16 Effective in January 2006, pharmacists were recognized providers of MTM as defined under the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA) Part D Prescription Drug Benefit.17 It has been clearly recognized that collaborative MTM can maximize patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and reduce the frequency of preventable drug-related problems. In this team approach, drug therapy decision making and management are coordinated through the collaboration of pharmacists, physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals. This framework identifies five core components: medication therapy review, a personal medical record or list, action plan, intervention and referral, and documentation with follow-up. These are the components you should use when seeing patients, and you should discuss them with IT personnel when they are creating or defining the EMR templates for your patient encounters. MTM is a prime example of why the manual chart and/or the EMR need to be altered to accommodate the pharmacists’ role in the patient’s care.16

CASE

By adopting the office templates for diabetic management and creating a template specifically for anticoagulation visits, you were able to select sections of the SOAP note that worked for your type of visits. You also were able to prompt Dr. Busybee in your note when a patient was due for preventive care visits and even immunizations. Adapting to the existing documentation system also assisted the other practitioners in your office to read and understand your plan of care for patients, which allowed for a team approach to the care of the patient.

When you participate in collaborative MTM, you will document your activities in a PMR that you make available to other health care professionals in a timely fashion through established channels of communication.1,6,7,17 Since documentation standards vary state to state, you should develop and implement collaborative practice agreements, patient referral processes, and the practice settings in accordance with the laws in your state. Please refer back to Chapter 1 for more detail on collaborative practice agreements.

HIPPAA Safety Measures

The issue of patient confidentiality and security of documented medical information continues to be debated and discussed. This has been especially relevant in the transition to electronic media for the majority of the patient’s medical information. Details on what an organization or provider must do to meet HIPAA requirements are lacking, but the law does state that health care organizations must “implement physical safeguards for all workstations that access electronic protected health information, to restrict access to authorized users.” As a provider, you are expected to log out when leaving a workstation, use a privacy screen to prevent viewing by unauthorized people, and remove workstations from high traffic areas.18 In response to these measures, it is important that you have your own access code, whether it is a password or biometric fingerprint, so that electronic media is secure. Also, you should not electronically document “under” a physician or nurse practitioner who may see the patient at the same appointment since this does not reflect your encounter and could lead to confusion over your assessment and plan for the patient. In addition, students should be blocked from entering any data into the system without your approval and signature. Maintaining patient privacy is critical. If needed, you may wish to provide some basic training to students and others on the inappropriateness of discussing patient information in hallways, elevators, at lunch, or even with others not working at the site. It is a good idea to have all health care providers visiting the practice, including students, residents, technicians, etc., sign a confidentiality statement regarding patient information.

All medical records must be maintained in a safe and secure area with safeguards to prevent loss, destruction, and tampering. Your documentation within the medical record may physically exist in separate and multiple locations in both paper-based and electronic formats, depending on the practice site(s). However, chronology is essential, so pay close attention to ensure that documents are filed properly or the information is entered in the correct encounter record for the correct patient, including appropriate scanning and indexing of imaged documents at all practice site(s). All PMRs are retained for at least as long as required by state and federal law and regulations and must be maintained in their entirety regardless of form or format. Note that federal law supersedes state law unless the state is stricter than the federal government. Written or electronic, no documentation entries may be deleted from the record except in accordance with the destruction policy. If your written PMR is microfilmed or kept on a computer database, there should be a written policy at your site concerning PMRs, outlining who is custodian and where the original PMRs are stored. This type of record keeping is crucial as offices implement EMRs yet must maintain the outdated written chart as required by state law.19

HIPAA waivers have language requesting patient consent regarding the collection of information, use in research, and disclosure of patient’s personal information as required. This also includes who will be sharing in the information, patients’ right to access their own information (medication list, lab results, and list of diagnoses), and the patients’ right to submit a complaint. In addition, print or electronic documentation must be stored appropriately to ensure confidentiality. Patients also need to consent when clinical documentation and other health information is transferred to other providers. No matter what system is used for storage of information, access should be monitored and limited to only those clinicians directly involved with the patient’s care.20

Documenting Medication Reconciliation

Medication reconciliation and verification of a current and accurate medication list is arguably one of the more important documentation activities performed to maintain patient safety and improve patient outcomes for any transition of care. Medication reconciliation reduces errors in transcription, omission, duplication of therapy, indication for use, and drug-drug and drug-disease interactions.21 The simple act of comparing the drugs that the patient reports taking at home against a recently documented medication administration record (MAR) in either an office or institutional setting allows a cross-check and can help alleviate the approximately 4.7% of hospital admissions linked to adverse drug reactions. In addition, the impact made possible by pharmacists performing this role will help to create opportunities to build collaborative relationships with other health care professionals and patients.22

We are focusing on medication reconciliation because its importance extends beyond the setting of patients entering and leaving the hospital. As we know, the transition of patient care to the outpatient setting and among the various ambulatory providers allows gaps in information, especially since most outpatient sites are not linked with each other or with extended-care facilities, health systems, and their hospitals. Additionally, significant errors occur secondary to the many modifications to medication dosages, over-the-counter (OTC) use, and adherence issues patients experience that are often seen by ambulatory pharmacists in their daily practice. Taking responsibility to resolve or prevent these types of errors is what makes medication reconciliation the backbone of pharmacy clinical services. Your expertise lends itself to a thorough and detailed medication history that is then documented in the PMR. Documentation is essential for medication reconciliation to be effective. It should not stop at the medication list, as records regarding side effects, allergies, drug interactions, and cost issues are often as important as medication history for optimal care of the ambulatory patient.1,6,7,22,23

The EMR creates a new dimension in medication reconciliation and medication list collection and storage. However, the record is only as strong as the accuracy of what is being documented. In most cases, the ability to transfer the list electronically to another system does not exist. Gaps remain in documenting medication use in the majority of EMRs. Ernest and colleagues illustrate as many as one of every four medications was associated with discrepant information in the patient medical record.28 Emphasis has been placed on transition to and from inpatient care, but as previously mentioned, this needs to be taken further by those of us practicing in the outpatient setting. Methods to ensure accuracy and transferability of the medication lists in both the electronic and paper format need to be developed, implemented, and maintained and measured for accuracy.24 Content standards need to be developed and agreed upon to enable interoperability.

No matter if the documentation system is electronic or manual, medication reconciliation should occur at each office visit and include all medications, not just those associated with a particular visit. Pharmacists play a key role in preventing medication errors and enhancing care by simply documenting and updating medication records on a continual basis.24

Communication Techniques

Documentation using a clinical encounter note is an effective way to communicate what has occurred at an office visit. Documentation is only as strong as the data gathered, thus it is very important for you to also effectively communicate with your patients during the visit. Employing communication techniques, such as motivational interviewing or assessing the patient’s health care literacy level, will aid you in gathering the most useful information from your patient. Good communication will enable you to synthesize and analyze (assessment) the information gathered to create a specific plan for care that meets the patient’s needs.

CASE

Over the last 6 months, your practice continues to grow as other patients and providers of the practice hear about your service. You approach Dr. Busybee about expanding the services you provide by offering to include a formal medication reconciliation services and assessment of each patient’s health care literacy level. Since this does not conflict with the office process or the original business model, Dr. Busybee sees this as a win-win for his office and his patients and approves you adding these services to your office hours. You are pleased with his vote of confidence, but realize while medication reconciliation seems easy, some questions remain: what do I need to be effective at performing these new services and how will I document my impact?

Communication Tips

Establish rapport early in the encounter with your patient through a welcoming introduction to you and your clinic. Patients can easily sense authenticity in their providers, so most importantly you should be relaxed, confident, and attentive to the patient and the encounter. After ensuring that you and your patient are comfortable and ready to start the visit, conduct the interview with open-ended questions. Doing so enables patients to tell you their health care story in their own words. It is important to frequently pause and summarize or reflect back to the patient so that you may verify accuracy and your correct understanding of the patient’s story. Listening is an important communication tool. Documentation of the encounter can include subjective and objective findings that employ the “basic seven” line of questioning. Other question series commonly used are the Indian Health Service Counseling Model, the PQRST method, and QuEST Scholar method.25,26 (See web toolkit.) ![]()

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is an effective technique that can be incorporated into the patient interview process. Developed in 1991 by Miller and Rollnick, MI uses a patient empowerment approach throughout the encounter.27 Although MI and another interview style called the transtheoretical model (Prochaska and colleagues, developed in 2004) were developed independently; there is some similarity between them.28 Both assume that people approach change with varying levels of readiness. Historically, MI has been used for patients with drug and alcohol addiction and works from the assumption that many patients who seek therapy are ambivalent about change, but their motivation changes during treatment. The four basic principles of MI are as follows: (1) express empathy, (2) develop discrepancy, (3) roll with resistance, and (4) support self-efficacy. As a pharmacist, you can assume the role of patient mentor or coach to aid patients in making behavior changes by creating “self-selected” patient goals. Documentation should include these goals, which use the SMART acronym: specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time-bound relative to behavioral and lifestyle modification.29 A great clinical example of how to use MI is in smoking cessation. By helping the patient create goals and then working with him or her on the appropriate pharmacologic management choices, you can play a large role in assisting your patient to kick the habit.

Health Care Literacy

As discussed, there are a number of best practices that apply when conducting a patient encounter, but no matter which communication technique is employed, you must have an understanding of the patient’s level of health literacy. Health care literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”30

The National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) provided the first measure of U.S. health literacy. Survey findings showed 14% of U.S. adults function at below the basic level, 22% function at the basic level, 53% have an intermediate level of health literacy, and 12% have proficient health literacy. Note that interpreting medication labels requires intermediate skill. This means that 36% of adult Americans have levels of health literacy below what is required to understand typical medication information.31 Low health literacy is a problem that touches all groups and segments of our society (elderly, minorities, homeless, poor, poorly educated, etc). Several studies have assessed patients’ understanding of their medications. Individuals with limited health literacy demonstrated 12–18 times the odds of being unable to identify their own medications and distinguish one from the other. Patients who have difficulty understanding simple instructions such as taking a medication every 6 hours or on an empty stomach have insufficient understanding of common drug mechanisms and side effects and greater misinterpretation of drug warning labels.32-37

Several tools are available to analyze the readability of patient education materials. Examples include the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level and Reading Ease and the Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) index. There are also resources to test the health literacy of those who need it, such as the rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine (REALM) and the test of functional health literacy in adults (TOFHLA), which are validated instruments. Additional assessments available are the tools for real-time assessment of health information literacy skills (TRAILS) and the newest vital sign (NVS) by Pfizer’s clear health communication, as well as those from Medline-Plus, National Institute for Literacy (NIFL), Plain English Network, the American Medication Association (AMA), and Harvard School of Public Health. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has a Pharmacy Health Literacy Assessment Tool User’s Guide on their web site to assess health literacy for pharmacies and has a survey accessible through the public domain.38

|

All patients can benefit from five recommended strategies for patient-centered visits:32,38,39 |

1. Use plain language and avoid medical jargon and vague instructions.

2. KISS (keep it short and simple). Tell patients what they need to know.

3. Ask patients to “teach back” what they have learned.

4. Recognize variation in learning styles and preferences, thus verbal messages should be reinforced with written information and images.

5. Everyone learns better if information is reinforced in multiple ways.

Once literacy level is established, it is essential to document the information within the PMR to assist everyone who is caring for the patient. This is true for both health care literacy and literacy skills in general, including English as a second language (ESOL) and learning disabilities.38,39 Many times pharmacists are the only ones assessing literacy because we are asked to consult on the nonadherent patient or the patient who cannot seem to use medications correctly. Before you accept that the patient is voluntarily nonadherent, assess literacy level, language skills, and any apparent learning disabilities to determine if they play a role in problems the patient is experiencing. That simple act will make you a hero in the patient’s eyes, but it will also affect how they are cared for by others as well as the communication style when educating the patient at future encounters. (Literacy Links) ![]()

Medical Liability and Auditing

Performance Evaluation

The scope of professional liability has increased parallel to the increase in pharmacists’ scope of practice. Historically, pharmacists have functioned and intervened as learned intermediaries under the direct supervision of a physician’s verbal or written orders. This paradigm shift of pharmacists practicing as independent providers places more responsibility on pharmacists as medication therapy experts, thus documentation of care is essential to protect pharmacists from liability.1

CASE

It has been 1 year since you submitted your business plan to Dr. Busybee. At three months he reminded you that he expected evidence of the impact you have had on his patient population. At that time you began using the EMR to track HgbA1c levels and INR trends for your patients. When you added medication reconciliation and health literacy screening to your service, you expanded your metrics to include compliance checks as well as number of admissions to the local hospital due to a diabetes and/or anticoagulation complications. Using the EMR you were able to show percentage of your patients that achieved treatment goals including compliance with medications, appointments, and lab work. Dr. Busybee was impressed and shared your impact with his partners, who in turn used the local trends to gauge your impact versus patients who did not have access to a pharmacist.

Awareness of this trend shows that it is vastly important that every pharmacist who participates in direct patient care and documents in the PMR have a mechanism in place that tracks performance, continuous quality improvement, and adherence to practice standards. For those using an EMR for documentation, they may have potential for greater ease of measuring ambulatory care-based quality outcomes and errors; however, all clinical documentation can be used to track impact of care.40 Outcome tracking mechanisms need to be developed using proper documentation that allows for a standardized approach to find and apply patient data to determine if quality standards have been achieved. Integrating pharmacy service benchmarks into a PMR will require a close look at how it can be used to document the effectiveness of pharmacy services and possibly justify expansion of resources and personnel. You should be planning ahead to determine the capabilities of the PMR format used by the practice so it can be designed to find and track your documentation easily, by using certain parameters. This was alluded to in the first part of the chapter regarding how to create your templates for each of your patient encounters. That upfront research and implementation will pay off as you set up your continuous quality improvement and performance measures for your practice. Chapter 7 will provide greater detail on quality and performance measurement.

An EMR note could be applied to assessing quality by looking at how point-of-care testing is documented within your electronic encounter note. With the EMR, only certain fields of the note may be included in parameter searches, but by creating the right template and choosing the correct field, you should be able to track and graph INRs to illustrate your success in keeping patients with the therapeutic range. Another example of using the EMR is to highlight potential problems before they occur, such as searching a database for patients with diabetes who take metformin and cross reference that information with serum creatinine levels. This type of quality assurance initiative will aid in identifying at-risk patients with a potential for an adverse drug event before it happens.40

As we have discussed, some EMRs are more robust than others, so it is imperative to discuss with IT personnel how such information can be gathered and formatted in a searchable field.

Chart Audits

One question that is frequently asked is who will be setting up and evaluating pharmacists’ performance. Audits are a tool used by ambulatory professionals to assess if an office is meeting designated thresholds for quality. Audits help deviations from standards in patient care and documentation in the patient care process. Many pharmacists have never heard of chart audits. However, with the greater emphasis on quality in health care reform and as we assume the role of independent practitioners, all pharmacists need to develop a protocol and have procedures in place to monitor the quality of services. Thorough documentation of patient care encounters and compliance with CMS standards are key in meeting standards set forth by you and your practice site. You may wish to perform quarterly chart audits and report on what you and your organization consider to be important performance evaluation parameters.

CASE

Since you were able to show an impact for Dr. Busybee’s patients, many of his partners have started referring patients to you for care. Realizing you are taking on more responsibility, you approach Dr. Busybee and ask how he keeps track of his impact. You inquire if there is a way to assure you are providing the appropriate care, not just metrics or outcomes. Dr. Busybee suggests that you become integrated into the chart audit protocol the physicians and nurse practitioner use in the office to assess quality of care.

Audits are commonly conducted through peer evaluation where each member of the outpatient clinical team reviews the PMRs of colleagues using a predetermined set of criteria and threshold quality markers. Areas of emphasis may include appropriate labs ordered, medication reconciliation, monitoring parameters, level of patient adherence, preventative measures, screenings, or clinical outcome measures and goals. This applies to all midlevel providers and all remote sites where you practice, thus your audit does not have to be done by another pharmacist; it can be done by other clinicians in the office. Audit procedures are often handled by a continuous quality (CQI) committee. They create the parameters from established standards and billing requirements that are used in auditing the various providers. The purpose of a chart audit is to provide feedback to the clinician to improve patient care, improve accuracy of information recorded, and to ensure thorough documentation practices.1 (Auditing Tool) ![]()

The key points you should consider in the peer review process are as follows:41

- Placement of blame, finger-pointing, and conflicts with other caregivers should be resolved through the quality improvement process and does not belong in medical record.

- Subjective terms should be avoided. Subjective opinions by physicians and nonphysician clinicians (NPC) open up liability issues. Documentation should be as factual as possible.

- Hospital staff, facility, or equipment concerns should be addressed in an incident report completed by the hospital administration.

- Do not document conversations with the attorney, insurance carrier, or risk manager in the medical record. If necessary, document separately.

- Incident reports can be protected from discovery if they are part of a peer-review process, although they can be discovered through a review of the medical record when attorneys become aware of their existence. Likewise, chart audits can ensure adequate coding and complexity to protect against fraud and liability with CMS.

The key points you should consider in the chart audit process are as follows:

- Look for under- or overdocumentation in your charts that can raise flags for improper coding selection.

- Ensure that appropriate levels of service are identified and billed.

- Learn the proper steps for choosing appropriate levels of history, exam, and medical decision making (evaluation and management codes are discussed in Chapter 8).

- Get the chart audit forms to implement your internal audit program.

- Learn how to audit based on coding facts and potentially uncover missed revenue.

- Make the chart audit an essential component of the compliance plan.

Professional Liability

Liability, as it relates to clinical documentation, can be an issue when (1) payment challenge is ensuing for service rendered or not rendered or (2) legal action is ensuing as a result of an action or nonaction taken by the provider. In both situations, your documentation will provide the necessary information to manage the process discovery and review of professional conduct.1

|

The importance of good documentation cannot be any more important than when you are defending your decisions and actions regarding patient care. |

This means that documentation must be accurate and organized. By any means, you want to avoid any activity that can be misconstrued as fraud. By CMS definition, fraud is “the intentional deception or misrepresentation that an individual knows to be false or does not believe to be true and makes, knowing that the deception could result in some unauthorized benefit to him/herself or some other person” or “to purposely bill for services that were never given or to bill for a service that has a higher reimbursement than the service produced.”42

|

This definition drives home the point that what we document needs to be accurate, factual, and thorough, since we are all aware that if the chart does not reflect the care given, then the actions never happened according to our legal system. |

Historically, we have acted as record keepers for medication use as well as drug interactions and adverse drug events. Now our documentation standards have been adjusted and expanded to show the care we provide as health care practitioners.

A key element that all documentation should include is the assessment of the situation within the realm of care given. If you cannot address the problem, or it is out of your scope of practice, there must be documentation of how other health care team members (referring provider or interdisciplinary colleagues) were involved to address the needs of the patient. In addition, your plan of action must be concise yet complete. The ideal documentation includes how you affected care, planned for upcoming visits, and intervened to provide preventive care. For an example, refer back to the SOAP note and notice how part of the plan was to have the patient follow up with certain specialists (standards of care) as outlined by the ADA guidelines. Many pharmacists forget that as a patient advocate you have the power to ensure appropriate care is given to your patient. By communicating thoughts, actions, and plans for the patient, you can assist the next member of your team to provide high-quality care and protect yourself and others from liability.1,6,7

Chapter Summary

As you can see, documentation plays a vital role in your everyday professional life. It allows communication between you and other health care practitioners while also providing evidence of what occurred during the patient encounters. Don’t forget that multiple providers impact a patient’s care, thus you must continue to develop your communication skills not only with other health care providers and patients but also with each other.

Health information technology is being implemented faster than most realize and, while this advancement has its disadvantages, the one area of improvement will eventually be communication between and within health systems. Electronic documentation is the future; by allowing practitioners to collect patient history, reports, prescription information, and reimbursement data, this format will continue to push for proper and thorough documentation so all health care providers can make the most informed clinical decisions possible for patients. In the end, documentation is an essential component to a successful partnership between providers regardless of their degree, location, or specialty.

References

| 1. | Zierler-Brown (Haines) SL, Brown TR, Chen D, et al. Clinical documentation for patient care: Models, concepts and liability considerations for pharmacists. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1851-1858. |

| 2. | Webster L, Spiro RF. Health information technology: A new world for pharmacy. JAPhA. 2010;50:e20-e34. |

| 3. | American Medical Association. Electronic medical record implementation and technical guides. https://catalog.ama-assn.org/Catalog/product/product_list?_requested=797127. Accessed August 7, 2010. |

| 4. | American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 2015 Initiative. Goal 5: Increase the extent to which health systems apply technology effectively to improve the safety of medications use. Published 2007. www.ashp.org/s_ashp/doc1c.asp?CID=421&DID=4024. Accessed August 7, 2010. |

| 5. | Brock KA, Casper KA, Green TR, et al. Documentation of patient care services in a community pharmacy setting. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2006;46:378-384. |

| 6. | ASHP. Guidelines on a Standardized Method for Pharmaceutical Care; Best Practices for Hospital and Health-System Pharmacy: Position and Guidance Documents of ASHP, 2005-2006 ed. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2005:183-191. |

| 7. | ASHP. ASHP guidelines on documenting pharmaceutical care in patient medical records. Best Practices for Hospital and Health-System Pharmacy. Position and Guidance Documents of ASHP, 2005-2006 ed. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2005:192-194. |

| 8. | Rovers JP, Currie JD, Hagel HP, et al. A Practical Guide to Pharmaceutical Care. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 1998. |

| 9. | Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47:533-543. |

| 10. | McDonald CJ, Tierney WM. Computer-based medical records: Their future role in medical practice. JAMA. 1998;259:3433-3440. |

| 11. | Pronovost P, Weast B, Schwarz M, et al. Medication reconciliation: A practical tool to reduce the risk of medication errors. J Crit Care. 2003;18:201-205. |

| 12. | ASHP Continuity of Care Task Force. Continuity of care in medication management: Review of issues and considerations for pharmacy. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1714-1720. |

| 13. | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Glossary. www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/glossary/default.asp?Letter=ALL&Language=English. Accessed August 7, 2010. |

| 14. | Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low density lipoprotein cholesterol, a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2563-2571. |

| 15. | Cranor C, Bunting B, Christenson D. The Asheville Project: long-term clinical and economic outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43:173-184. |

| 16. | American Pharmacists Association and National Association of Chain Drug Stores. Medication therapy in community pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service (version 2.0). J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008; 1-24. |

| 17. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rules and regulations. Fed Regist. 2005;70:4541. |

| 18. | HIPAA Requires Organizations to Secure Their Electronic Devices. http://www.ashp.org/menu/News/Pharmacy/News/NewsArticle.aspx?id=884. Health System Pharmacy News. Accessed March 25, 2010. |

| 19. | American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA). Legal medical record standards. http://www.ahima.org/infocenter/guidelines/ltcs/5.1.asp. Accessed August 7, 2010. |

| 20. | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/. Accessed on August 7, 2010. |

| 21. | Lee JK, Grace KA, Taylor AJ. Effect of a pharmacy care program on medication adherence and persistence, blood pressure, and low density lipoprotein cholesterol, a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2563-2571. |

| 22. | Manasse H Jr, Thompson K. Medication Safety: A Guide for Health Care Facilities. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2005:4-5. |

| 23. | Shojania KG, Duncan BW, McDonald KM, et al., eds. Making Healthcare Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report No. 43 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD: AHRQ Publication No. 01-E058; 2001. |

| 24. | Ernest ME, Brown GL, Klepser TB, et al. Medication discrepancies in an outpatient electronic medical record. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2001;58:2072-2075. |

| 25. | McDonough RP, Bennett MS. Improving communication skills of pharmacy students through effective precepting. AJPE. 2006;70(3):Article 58, 1-12. |

| 26. | Buring SM, Kirby J, Conrad WF. A structured approach for teaching students to council self-care patients AJPE. 2007;72(1):Article 20, 1-7. |

| 27. | DiClemente CC, Velasquez MW. Motivational interviewing and the stages of change. In: Miller WR, Rollnick S, eds. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd edition. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002:217-250. |

| 28. | Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing Traditional Boundaries of Therapy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin; 1984. |

| 29. | Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am J Psychol. 2009;64(6):527-537. |

| 30. | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. 2nd ed. With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2 vols. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. |

| 31. | Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, et al. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. |

| 32. | Kripalani S, Henderson LE, Chiu EY, et al. Predictors of medication self-management skill in a low-literacy population. J Gen Int Med. 2006;21(8):803-900. |

| 33. | Kripalani S, Weiss BD. Teaching about health literacy and clear communication. J Gen Int Med. 2006;21(8):888-890. |

| 34. | Gazmararian JA, Baker DW, Williams MV, et al. Health literacy among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. JAMA. 1999;281:545-551. |

| 35. | Gazmararian JA, Kripalani S, Miller MJ, et al. Factors associated with medication refill adherence in cardiovascular-related diseases: A focus on health literacy. J Gen Int Med. 2006;21(12):1215-1221. |

| 36. | Fang MC, Machtinger EL, Wang F, et al. health literacy and anticoagulation-related outcomes among patients taking warfarin. J Gen Int Med. 2006;21(8):841-846. |

| 37. | Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF III, et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J Gen Int Med. 2006;21(8):847-851. |

| 38. | Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. AMA and AMA Foundation; 2003. |

| 39. | Weiss BD. Epidemiology of low health literacy. In: Schwartzberg JG, VanGeest JB, Wang CC, eds. Understanding Health Literacy: Implications for Medicine and Public Health. AMA Press; 2005:19. |

| 40. | Dunham DP, Baker D. Use of electronic medical record to detect patients at high risk for metformin-induced lactic acidosis. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2006;63:657-660. |

| 41. | Bradshaw RW. Using peer review for self-audits of medical record documentation. AAFP; 2000. http://www.aafp.org/fpm/20000400/28usin.html. Accessed August 7, 2010. |

| 42. | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Most common medical rip off and fraud schemes. www.cms.hhs.gov/fraudAbuseforConsumers/04_Rip_Offs_Schemes.asp. Accessed August 7, 2010. |

Additional Selected References

Freidland RB. Understanding Health Literacy: New Estimates of the Costs of Inadequate Health Literacy. Washington, DC: National Academy on an Aging Society; 1998.

Howard DH, Gazmararian J, Parker RM. The impact of low health literacy on the medical costs of Medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Med. 2005;118(4):371-377.

Katz MG, Jacobson TA, Veledar E, et al. Patient literacy and question-asking behavior during the medical encounter: A mixed-methods analysis. J Gen Int Med. 2007;22(6):782-786.

Kirsch I, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, et al. Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Results of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education; 1993.

Community MTM.www.communitymtm.com. Accessed March 25, 2010.

ConXus MTM. www.pdhi.com. Accessed March 25, 2010.

Outcomes MTM System. www.getoutcomes.com. Accessed March 25, 2010.

PIDS-Pocket PC Based MTM System. www.rxinterventions.com. Accessed March 25, 2010.

PillHelps Works. www.pillhelp.com. Accessed March 25, 2010.

Medication Management Systems. www.medsmanagement.com. Accessed March 25, 2010.

Mirixa Pro & Mirixa Edge. http://www.mirixa.com. Accessed March 25, 2010.

EPIC Integrated Software. http://www.epic.com. Accessed March 25, 2010.

MCKesson Practice Partner. http://www.practicepartner.com. Accessed March 25, 2010.

Web Resources

Chart Audit Tool

Example Documentation Elements for EMR/PMR

Examples of Community-based/Clinical Pharmacy Documentation Software Web Sources

Example of Electronic Documentation of a Pharmacy Office Visit

Example SOAP Note and 7 Lines of Questioning

Link to AMA Web Site for Bookstore (three books on EMRs)

| Web Toolkit available at www.ashp.org/ambulatorypractice |

Chapter Outline

| Web Toolkit available at www.ashp.org/ambulatorypractice |

Chapter Objectives

1. Identify the relevance for pharmacists’ documentation of clinical services.

2. Compare and contrast manual and electronic documentation systems.

3. Review the common documentation styles and communication techniques used in clinical practice.

4. Recognize the appropriate levels for billing based on an example of documentation.

5. Discuss continuous quality assurance and other safety measures when implementing and maintaining documentation.

Introduction

Regardless of your practice environment, you will need to use electronic and manual methods of documentation to communicate, exchange information, and educate patients, caregivers, and other health care professionals. Like other health care providers, you will primarily use the patient medical record (PMR) for documentation of patient care. Through efficient and comprehensive documentation you can (1) meet professional standards and legal requirements, (2) communicate with other health care professionals, (3) establish accountability for medication-related aspects of direct patient care, (4) strengthen transition and continuity of care, (5) create your record of critical thinking and judgment, (6) provide evidence of your value and workload allocation, (7) justify reimbursement for cognitive services, and (8) provide needed data for tracking of patient health outcomes.1

Currently, industry-driven advances in technology are having a profound effect on how pharmacists document and are also creating new challenges. With the passage by Congress of the stimulus package (the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, or ARRA), expansion of health information technology (HITCH) is now mandated by the U.S. government. ARRA budgeted approximately $150 billion for health care reform and close to $34 billion for health care provider adoption of HITCH and a nationwide health record system by 2014.2 The most critical element to the e-health system is the electronic medical record (EMR) and the electronic health record (EHR). An EMR is a portal that shares relevant patient information among health care professionals. Likewise, it can perform as a patient scheduler and an intraoffice messaging system as well as assist with laboratory communications, e-prescribing, and billing processing. An EHR is an individual patient medical record digitized from many locations or sources, including the patient and family members. It can interface with evidenced-based treatment algorithms and protocols, outcomes reporting, and quality assurance and is synonymous with what is also called the patient medical record (PMR). An electronic personal health record (ePHR) can be created by patients, physicians, pharmacies, health systems, and other sources, but originates from a patient.2

An EMR and EHR can enhance provider communication in all health care settings. EMRs are primarily focused on physician and hospital-based practice, but there is potential for benefit in pharmacy practice with wider implementation. EMR adoption is predicted to bring the following patient and health care provider benefits: lower costs, quality care, improved reimbursement, enhanced productivity, efficiency, effectiveness, and communication.2

While the EMR has promise of advancing patient care and can be a resource to capture patient encounters, it is not without its challenges. This is especially true in the primary care setting due to the sheer number and small size of ambulatory organizations. Pharmacists practicing in the ambulatory patient care arena have historically used a modified SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) note format to document patient encounters, with sections expanded or omitted based on relevance to the practice and scope or service. It has been physician, and not pharmacist, work flow that has driven creation, adoption, and integration of most outpatient EMR and PMR applications. Consequently, it has been difficult to alter or adapt a physician-driven EMR to fit the work-flow dynamics of a pharmacist-provided visit in the ambulatory setting. For example, most templates that fit individual disease states have predetermined signs and symptoms that are consistent with a pharmacist’s visit, such as documentation of hypo- or hyperglycemic symptoms for diabetes; however, pharmacists do not perform eye exams routinely, thus documenting a normal eye exam would be inappropriate in the template. This is where the EMR can be tricky for the pharmacist because both are normally included in a diabetes visit template. This is important since it relates to payment for clinical services. Although pharmacists do not perform detailed physical exams, we do address complexity, such as multiple disease states, some aspects of review of systems (ROSs) and physical exams (PEs), monitoring, follow-up, and capturing of outcomes. Documentation on templates is designed to emphasize and ensure that the appropriate information is in place for billing using the correct evaluation and management service codes. Using a template that has incomplete sections or that can be billed inappropriately (physician services versus a midlevel provider services) could result in devastating financial and legal consequences for your organization. Depending on your EMR, investigate whether it has the ability to code and recognize language used in your template to populate other fields in the PMR to ensure correct billing for your services, to collect data related to your services, and to generate a list of patients for whom you have provided care. If not, you should consider a separate clinical pharmacy documentation system to capture your needed documentation. Optimally it should integrate in some form or manner with your organization’s EMR.

CASE

In Dr. Busybee’s office they have already converted from a paper PMR to an EMR. Now that all the logistics of seeing patients in the office are resolved, you must determine how you want to document your interaction with each patient. After a review of the current EMR you noticed that none of the disease state templates address anticoagulation management; however, the good news is the diabetes management template used by the physicians could be used for your visits as well. Knowing that you have no built-in system to document care given for patients using an anticoagulant, you approach the office manager about changing the EMR. The office manager promptly tells you this is outside their expertise and that they want nothing to do with changing the EMR setup. Dr. Busybee really does not understand why you cannot just type your encounter note into the EMR. You attempt to explain the volume of patients and the time commitment for that type of documentation. His response is “We use the EMR in this office — make it work so I can start referring patients to you as soon as possible.”

Because EMRs generally are not created with clinical pharmacy practice in mind, you may have already concluded it will be important for you to collaborate with your institutional information technology (IT) personnel as well as pharmacy management system (PMS) vendors as needed to develop the necessary technical integration solutions that incorporate your work flow and corresponding documentation requirements.2 This seems like a straightforward solution; however, many IT personnel have no experience with pharmacists seeing patients in an ambulatory setting or with the details of how we document, so they may be unwilling or lack sufficient knowledge to build a special area for a pharmacy visit within the adopted EMR. This can be further complicated by the fact that not all EMRs are created equally, and the adopted EMR may require a major system overhaul or significant financial outlay to accommodate your clinical services. You should be prepared to educate IT personnel on how you document your patient encounters, such as the need for a universal template for all pharmacotherapy-based visits and specific disease-state templates (e.g., diabetes or anticoagulation). An existing physician template may be used with minor or no alterations.

How do you know which type of templates work for you within an EMR? Just like other challenges in the pharmacy world you will need to research and investigate the functionality of the proposed or current EMR at your site. Visit the EMR vendor web page and familiarize yourself with the advantages and disadvantages of the application and whether the system can address the needs of midlevel providers such as the clinical pharmacist. Reviewing articles and attending lecture series as well as professional meetings may help, but usually it requires your review of your particular system to solidify its application to your services. One resource is the American Medical Association’s online bookstore.3 Currently, there are several books available that discuss types of EMRs, as well as incorporation and maintenance of the systems. (AMA web site) ![]() Granted, pharmacists rarely have a vote in the decision regarding which system is purchased for outpatient services, but such EMR resources can educate you on which systems allow specialization and customization and which are more restrictive in adapting to midlevel provider patient care services.

Granted, pharmacists rarely have a vote in the decision regarding which system is purchased for outpatient services, but such EMR resources can educate you on which systems allow specialization and customization and which are more restrictive in adapting to midlevel provider patient care services.

Once you understand your EMR’s flexibility and how your services will integrate into the EMR system, you can begin to create or adapt your current manual patient care notes to an electronic template format. The majority of EMRs do use a SOAP-based format, but it may appear unrecognizable because many systems follow a point-and-click process rather than use free text for documenting. No matter which format, you will have to integrate your documentation within the systematic approach designed by the EMR’s manufacturer. It is imperative that your documentation work flow be developed with your input and feedback to ensure the documentation process is efficient, easy to use, synergistic with the flow of the patient visit, and captures all the needed information. If the process is not scrutinized thoroughly, you may find yourself inefficiently jumping around the screen or having to type a large amount within your template; this leads to less time spent seeing patients and ultimately decreasing productivity and reducing reimbursement, which affects the viability of your practice.

One solution is to critically assess work flow with IT assistance to create an electronic template that is geared toward practice functions (pre-visit information gathering, visit documentation, orders you are able to execute, and billing) as well as the type of patient care visits you encountered. One example is an anticoagulation visit in which the international normalized ratio (INR) is obtained by the nursing staff while they are doing vitals and preparing the patient room for the office visit. You may then enter the room to complete your visit with information already entered into the electronic note. Alternatively, you, a resident, or your advanced practice clerkship student could be responsible for performing vitals, point-of-care testing, and the interview. The work flow and thus the note would be different. The key is to create your template around the structure and flow of your patient visit. No matter which work flow and template is incorporated, your note should always contain the following elements:

- time of arrival and departure

- chief complaint

- history of present illness

- past medical history

- allergies

- social history

- family history

- appropriate referrals

- labs

- medication reconciliation

- assessment and plan

(Example Documentation Elements for EMR/PMR) ![]()

CASE