Physical Examination

- Elevated pulse and respiratory rate are nonspecific but suggest organic disease.

- Posture (leaning forward with the arms tripoding), accessory muscle use, and pursed-lip breathing suggest COPD.

- Examine for nasal polyps and purulent nasal discharge.

- Signs of current or past ear or nasal cartilage inflammation may suggest tracheal involvement from relapsing polychondritis or GPA.

Diagnostic Testing

Imaging

- Plain chest radiography:

- Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs (CXRs) should be one of the initial diagnostic evaluations.

- Attention should be paid to the presence of cardiomegaly, effusions, edema, and lung volume size.

- Location of lung involvement is also helpful for diagnosis:

- Lower lobe involvement is characteristic of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, rheumatologic disease, and asbestosis.

- Mid- and upper-lung zone development is associated with granulomatous diseases and silicosis.

- Lower lobe involvement is characteristic of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, rheumatologic disease, and asbestosis.

- Computed tomography (CT):

- Detects approximately 10% of cases of interstitial lung disease not visible on CXR.

- High-resolution CT (HRCT) may provide additional diagnostic clues and detect disease before it is clinically apparent.

- When performed with contrast, it may reveal thromboembolic disease.

- Echocardiography can reveal evidence of left ventricular dysfunction, valvular disease, and pericardial disease and can screen for pulmonary hypertension.

TREATMENT

- When possible, therapy should be directed by diagnosis.

- In general, supplemental oxygen should be adjusted to keep SpO2 ≥89% both at rest and with exertion.

- For those with chronic dyspnea and exercise intolerance, pulmonary rehabilitation may reduce symptoms and optimize functional status.4

Cough

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Cough is the sudden exhalation of lung gas mixture; chronic cough is one that lasts for at least 8 weeks.

- The first response to the initiation of a cough reflex is deep inhalation followed by glottic closure and then maximum forceful expiratory maneuver with glottic opening. This may or may not be associated with the expectoration of phlegm, sputum (mucoid or purulent), or blood.

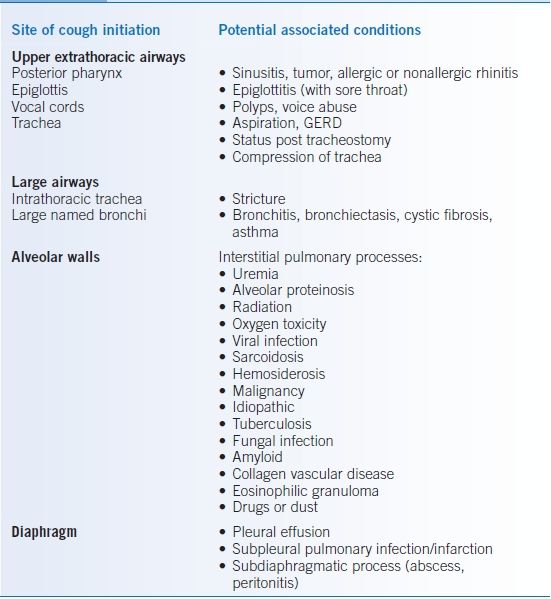

- Cough may be initiated by afferent stimulation of the upper airways structures such as the posterior pharynx, response to an inhaled irritant by larger airways, activation of stretch receptors of the alveolar wall, or stimulation of the diaphragm from either above or below.

- Identifying the etiology of cough is often a significant challenge.

- When the etiology is not immediately obvious, causes to consider include cough variant asthma, sinusitis or rhinitis with upper airway irritation, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), nonbacterial (fungal) endobronchial infection, and interstitial pulmonary processes.5–9

- A differential diagnosis is presented in Table 15-2.

TABLE 15-2 Causes of Cough

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- Recognition of the type and amount of expectoration often leads to a specific diagnosis.

- Nonproductive cough implies either a chronic irritating factor or an interstitial process potentially as simple as a viral pneumonitis or as complex as inflammation and/or scarring of the alveolar walls.

- When mucus production is reported, an inflammatory process (acute or chronic) is likely present and may be associated with infection.

- Mucus production may not always be reported because of the social stigmata related to spitting.

Physical Examination

- Examine the ears for otitis, which is a rare cause of cough.

- Examine the nose for evidence of mucopurulent secretions, sinus tenderness, boggy turbinates, or polyps, all of which suggest upper airway irritation and perhaps a predisposition to asthma.

- Postnasal drip may also cause a cobblestone appearance of the tonsillar pillars/posterior pharynx.

- The throat should also be examined for signs of bulbar neurologic dysfunction.

Diagnostic Testing

- A CXR is a reasonable initial evaluation if the history and physical do not provide an adequate diagnosis. If it is abnormal, focus on directed evaluation of the abnormality. If it is normal, obtaining sputum cytology, microbiologic stains, and cultures is neither warranted nor cost-effective.

- Imaging of the paranasal sinuses by CT scan is superior to conventional imaging. Sensitivity is probably very good, but specificity is uncertain.

- Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) should be obtained if the prior workup is otherwise negative and symptoms do not resolve.

TREATMENT

- When possible, therapy should be directed by diagnosis.

- Antitussive medications including menthol, benzonatate, dextromethorphan, and codeine for refractory cases can be trialed for symptomatic relief.10–12

- In extreme cases, nebulized lidocaine may be employed.

Upper Airway Cough Syndrome (Postnasal Drip)

- Intranasal glucocorticoids are the most effective therapy for allergic rhinitis and are also effective for several types of nonallergic rhinitis including vasomotor rhinitis.

- Other therapies for rhinitis include oral antihistamines (first generation are preferred because of their anticholinergic effects), intranasal azelastine, and intranasal ipratropium bromide.13

- If therapy is unsuccessful in relieving symptoms in 2 weeks, consider obtaining a sinus CT scan.

Postviral Bronchial Hyperreactivity

- Tends to be resistant to therapy but fortunately is self-limited.

- Ipratropium bromide is more effective than placebo in reducing cough in this entity.14

- Evidence for efficacy of inhaled steroids and oral steroids is weaker, but they can be given if cough persists despite ipratropium use.

- Resistant cough should be treated with antitussives and reassurance.

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors mediate cough via accumulation of bradykinin.15

- Discontinuing ACE inhibitors often results in relief of symptoms in less than a week, and virtually all patients are better in 4 weeks.

- Changing the ACE inhibitor is unlikely to be effective as this is a class effect; however, alternatives such as angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) can often be used.

Hemoptysis

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Defined as coughing up blood from a pulmonary source.

- On occasion, hemoptysis is confused with hematemesis or the expectoration of blood from a nasal or pharyngeal source.

- Blood originates from the bronchial circulation in most cases but has a pulmonary arterial source in pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, Rasmussen aneurysms in tuberculous cavities, and the diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndromes of autoimmune origin.

- Hemoptysis is an infrequent complaint for those who seek primary care but is of great concern to the patient. When present in small amounts, the greatest concern is usually lung cancer. When there is a large amount, the event itself is frightening to the patient and the physician.

- Certain conditions are typically associated with hemoptysis: pneumonia, carcinoma of the lung, necrotizing pneumonitis, tuberculosis, acute and chronic bronchitis, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome), bronchiectasis, and cystic fibrosis.

- Of note, hemoptysis associated with anticoagulation therapy or hypocoagulable disease states usually develops only when there is an underlying pulmonary pathology.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- Obtain an estimate of the volume of hemoptysis. If the history suggests acute hemoptysis of ≥60 mL, refer the patient immediately to a hospital emergency department.

- Although differentiating massive versus nonmassive hemoptysis is controversial, 200 mL/day or 100 mL/hour can be used.16 Others define massive hemoptysis as that resulting in hemodynamic instability or gas exchange abnormalities.17

- Inquire about the appearance of the sputum.

- Frothy pink sputum suggests heart failure or mitral stenosis.

- Purulent sputum with fevers and chills suggests pneumonia.

- Chronic production of sputum with streaks of blood suggests bronchitis.

- Chronic large-volume purulent sputum punctated by episodes of frank blood suggests bronchiectasis.

- Frothy pink sputum suggests heart failure or mitral stenosis.

- Chest pain may accompany pulmonary embolism, lung cancer involving the parietal pleura, and pneumonia.

- Determine the smoking history, and obtain an occupational history, specifically addressing asbestos exposure as a risk factor for lung cancer.

Physical Examination

- Fever suggests an infectious cause.

- Examine the nasopharynx carefully to rule out an upper airway source of bleeding.

- Halitosis may accompany a lung abscess.

- Lymphadenopathy can be found in either malignancy or infection.

- Auscultate the chest for signs of consolidation (pneumonia), a pleural rub (pulmonary infarction, pneumonia), or a localized wheeze (bronchial obstruction by a neoplasm).

- Synovitis and rash may suggest vasculitis.

- Telangiectasia on face, lips, tongue, and fingers may indicate hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia with coexistent pulmonary involvement.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

- Obtain a complete blood cell count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time.

- Examine the urine for microscopic hematuria and red cell casts that may suggest a vasculitic pulmonary-renal syndrome, and obtain a serum creatinine.

- Evaluate sputum with a gram stain, acid-fast stain, culture, and cytologic examination.

- In cases in which pulmonary vasculitis is a consideration, obtain antinuclear antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

Imaging

- The CXR can localize an infiltrate or mass. Volume loss or atelectasis suggests bronchial obstruction. Pulmonary cavitation may occur with a lung abscess, tuberculosis, or necrosing cancer.

- High-resolution CT without contrast is the best method for a diagnosis of bronchiectasis. It is also excellent for the diagnosis of aspergilloma and may detect a broncholith. High-resolution chest CT with contrast is the test of choice for evaluating potential arteriovenous malformations.18

Diagnostic Procedures

- Fiberoptic bronchoscopy should be strongly considered in all patients with an abnormal CXR and hemoptysis. The diagnostic sensitivity varies from study to study depending on the population evaluated, but is at best localizing or diagnostic in approximately half of cases.19

- Identification of the bleeding site is three times more likely if bronchoscopy is done within 48 hours.20

- In the setting of massive hemoptysis, bronchoscopy is primarily performed to ensure airway patency, to maintain ventilation, and to perform endobronchial blockade to spare the opposite lung.

TREATMENT

- The treatment of small-volume hemoptysis is directed at the underlying disease process.

- Hemoptysis that is associated with chronic bronchitis and bronchiectasis should be treated with antibiotics and antitussives.

- Massive hemoptysis can be lethal and generally demands aggressive evaluation and treatment.21,22

Noncardiac Chest Pain

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Noncardiac chest pain is pain due to causes other than heart disease. Often referred to as atypical chest pain, it is generally used to include all chest pain that is not caused by coronary artery disease.

- Noncardiac chest discomfort is quite common in ambulatory practice. Its greatest importance lies in the concern it causes to patients and physicians alike that significant heart disease underlies the symptom.

- This discussion assumes that the presence of coronary disease has been evaluated and ruled out. The remaining common causes involve the chest wall, pleura, and esophagus. Diseases of the gallbladder, pancreas, large and small bowel, and psychiatric disorders account for much of the remainder.23

- Chest wall disorders:

- Musculoskeletal pain is more common than neurogenic pain.

- Costochondral and chondrosternal pain is frequently the result of exercise, injury, or inflammation.

- Rib fracture may occur from direct trauma.

- Intercostal or pectoral muscle strain may result from exercise.

- Nerve pain may be a result of preeruption herpes zoster or postviral or idiopathic neuritis.

- Musculoskeletal pain is more common than neurogenic pain.

- Pleural disorders:

- Viral pleuritis may follow coxsackie B infection.

- Pneumonia is often accompanied by pleural inflammation and sometimes pain.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus is often complicated by pleural involvement producing pain.

- Pulmonary infarction occurs in a minority of cases of pulmonary embolism but is often accompanied by pain.

- Gastrointestinal causes of pleural effusions, with or without pain, include pancreatitis and esophageal rupture.

- Viral pleuritis may follow coxsackie B infection.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- If one is notified of acute severe pain by phone, refer the patient to an emergency department for initial evaluation of coronary artery disease, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism, any of which may be rapidly fatal; office evaluation is not appropriate.

- Musculoskeletal pain is of widely varying duration, from a few seconds to days. The patient may notice that it hurts to touch or is worse with movements involving the trunk and arms.

- Neurologic pain is less likely to be increased by thoracic movement, but neck, arm, and shoulder movement may worsen nerve root irritation or thoracic outlet compression.

- Pleuritic pain is typically sharp and aggravated by inspiration and cough, but less so by movement. An exception is the pleural pain component that may accompany pericarditis.

- Esophageal pain is classically improved or relieved with antacids or H2 blockers, and the duration is typically longer than that caused by angina. However, it may be dull or heavy rather than burning with radiation to the neck or arm.

- Gallbladder pain is usually of acute onset, associated with nausea and vomiting, and felt in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium with radiation to the right shoulder.

- Pancreatitis usually presents with severe epigastric pain with radiation to the back, nausea, and vomiting.

Physical Examination

- Many ambulatory patients with noncardiac chest pain look well.

- Tachycardia may accompany any of the acute illnesses and is characteristic of pulmonary embolism and infarction.

- Palpate the chest wall for tenderness. Although characteristic of musculoskeletal pain, it may also be present in empyema, pleurodynia, and rarely pulmonary infarction.

- Percuss and auscultate for dullness or hyperresonance; the former may herald pleural effusion or consolidation, the latter pneumothorax.

- Palpate the abdomen for right upper quadrant tenderness and a Murphy sign.

- Inspect the skin for the characteristic vesicular eruption of herpes zoster.

- Examine the cervical and thoracic spine for any signs of tenderness, and determine if pain is worsened by cervical spine motion or vertical compression.

Diagnostic Testing

- Although patients may need no further evaluation given their presentation, obtaining a normal ECG may be worth its cost in providing the patient and physician with reassurance.

- If chest wall tenderness follows trauma or is accompanied by systemic symptoms, plain radiography of the ribs may show evidence of fracture or malignancy.

- Pain that is radicular and unremitting may warrant magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical or thoracic spine.

- If the symptoms suggest pleuropulmonary infection, obtain a CXR.

- Nonpleuritic pain without an obvious cause should prompt evaluation for a gastrointestinal source.

TREATMENT

Treatment is directed at the specific diagnosis that is responsible for the chest pain. Musculoskeletal pain is frequently controlled with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, which may also be helpful for nonspecific neuritis.

Pulmonary Function Tests

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

- Further evaluation of the above symptoms and signs is aided by objective assessment of pulmonary function.

- A detailed description of pulmonary function testing is beyond the scope of this chapter.

- PFTs neither provide a specific diagnosis nor determine disability. They simply quantify the degree of impairment of ventilation and gas exchange.

- In general, these measurements are performed at rest but can also be performed under the stress of exercise often uncovering more subtle impairment.

- In the pulmonary function laboratory, one can also assess ventilatory muscle function and determine the potential therapeutic effect of aerosolized bronchodilator medication and supplemental oxygen.

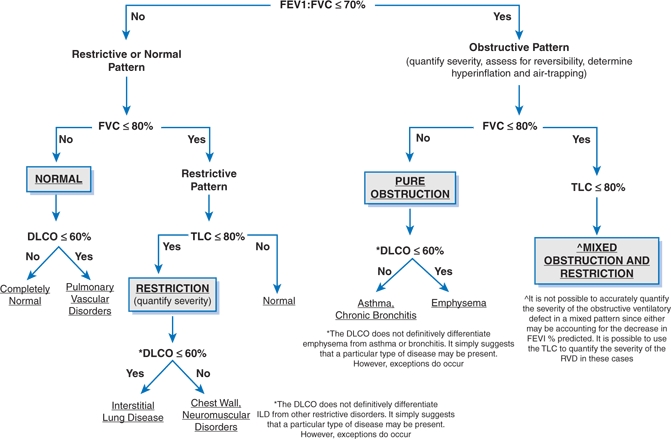

- The various PFTs available may be categorized as follows24:

- Spirometry: forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), the ratio of FEV1 to FVC, and peak expiratory flow (PEF)

- Lung volumes: total lung capacity (TLC), residual volume (RV), functional residual capacity (FRC), and expiratory reserve volume (ERV)

- Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO)

- Arterial blood gas analysis (ABG)

- Six-minute walk/oxygen assessment

- Cardiopulmonary exercise study

- Bronchoprovocative testing (methacholine challenge)25

- Spirometry: forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), the ratio of FEV1 to FVC, and peak expiratory flow (PEF)

INTERPRETATION

- Many pulmonary function studies are effort dependent; therefore, the first step of PFT interpretation is to assess the validity of the measured values.26–28

- Specifically, one asks, did the technician/patient interaction result in maximum patient effort? The general definition of validity is that the two best attempts are within 5%.

- When this is not the case, all may not be lost because the best test still represents a minimum level of the patient’s function, albeit less than the true maximum value.

- Figure 15-1 and Table 15-3 discuss the interpretation of PFTs.27,28

Figure 15-1 Initial evaluation of pulmonary function tests. DLCO, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ILD, interstitial lung disease; RVD, restrictive ventilatory defect; TLC, total lung capacity. Data from: Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretive strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005;26:948–968 and Al-Ashkar F, Mehta R, Mazzone PJ. Interpreting pulmonary function tests: recognize the pattern and the diagnosis will follow. Cleve Clin J Med 2003;70:886–881.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree