LEARNING OBJECTIVES

To describe the challenges that physicians face in maintaining excellence over the life of their professional career.

To identify best practices that physicians should follow to successfully engage in lifelong learning.

To communicate the role of physicians in leading and working within teams to achieve excellent patient outcomes.

To explain the roles that different organizations and accrediting bodies take to help ensure that physicians are achieving excellence in their practice.

INTRODUCTION

Dr. Amineh finished a busy day in her primary care office. Although most of her patients had routine concerns, several patients raised questions that she needed to look up in the literature. There was a dermatologic problem she couldn’t identify. One of her patients had been started on a new insulin regimen by her endocrinologist; Dr. Amineh had been to a continuing medical education (CME) program that mentioned this approach but couldn’t remember the details of how to adjust it or potential drug interactions. She hoped to get a few minutes at the end of the day after completing her chart notes to address these questions.

Despite widespread access to medical information on the Internet, people who fear that they are ill still turn to their trusted physicians for knowledge and wisdom as well as compassion. The trust they place in us is based on an assumption that all physicians live up to their professional commitment to excellence: a commitment to maintain the up-to-date knowledge and skills needed to treat their patients. The public believes that the highly selective and rigorous educational journey that physicians undertake to earn their MD degree has imbued them with the ability and the drive to maintain excellence over the life of their career. Every physician aspires to live up to this commitment. No one wants to be a good enough physician—we all want to be the best physician possible for our patients.

A commitment to strive for excellence is a key component of professionalism. As discussed in Chapter 3, A Brief History of Medicine’s Modern-Day Professionalism Movement, expertise in a body of knowledge is the core of a profession, and the social contract between the public and the profession requires that physicians maintain this competency. Fulfilling this obligation begins in medical school with the mastery of foundational social, biomedical, and behavioral science principles. It continues in practice with a commitment to continuously seek out, analyze, and apply the best available science and evidence to make patient care decisions, to continuously update procedural and clinical skills, and to acknowledge personal limitations. It is important to note that excellence today means demonstrating accountability by willingly participating in formal competency assessments as well as measurement of patient care process and outcome measurements throughout, not just at the start of, your career as a physician (Cassel & Holmboe, 2006; Weiss, 2010).

A commitment to excellence also means working with others to pursue improvements in safety, quality, patient satisfaction, and value in care delivery within your local care environment and within the larger institutions in which you practice (i.e., hospitals and integrated care systems). In appropriate settings, excellent physicians support research and education because they recognize that the biomedical advances that expand our capacity to reduce the burden of suffering and disease are the result of decades of carefully conducted scientific studies and the educational programs that have disseminated those results. Finally, excellence means understanding and working with the spectrum of organizations charged with ensuring the quality of physicians and healthcare institutions.

We know that excellence is an aspirational goal—the knowledge base of medicine is so large that we can only do our best to keep up to date with information in our field of practice. But striving to do so represents professionalism in action.

EXCELLENCE AND THE INDIVIDUAL PHYSICIAN

Physicians who enter practice today can expect to practice for three, four, or even five decades. Maintaining excellence for such an extended period is a tremendous challenge in today’s dynamic scientific environment. Scientific advances can dramatically change preventive, diagnostic, therapeutic, and procedural standards of care, requiring physicians to continuously update their practice. For example, in the 1980s, peptic ulcer disease was considered a mechanical problem and treated with antacids and surgery; in 2000 it was recognized as an infection treated with antibiotics. Table 6-1 outlines examples of dramatic changes in standards of care over the last 40 years.

| Condition | 1973 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Gold and high dose aspirin | Biologic response modifiers |

| Peptic ulcer disease | Antacids and surgery | Antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors |

| Advanced heart failure | Digoxin and diuretics | Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) Ultrafiltration Left ventricle assist devices Transplantation |

| Acute cholecystitis | Open cholecystectomy after several weeks of “cooling off” | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy within days |

| Suspected appendicitis | Exploratory laparotomy | Diagnostic ultrasound |

| Early stage breast cancer | Modified radical mastectomy | Lumpectomy and radiation therapy with adjuvant chemotherapy |

| Diabetes in hospitalized patients | Sliding scale insulin | Basal control with pre-meal supplementation |

| Red blood cell transfusion | Liberal | Conservative |

| HIV | Not recognized | Highly active antiretroviral therapy |

In addition to advances in scientific understanding of disease and therapies, our understanding of how physicians develop and maintain expertise over the life of their careers has changed. In the past, physicians believed lifelong learning involved simply setting time aside each day to scan the latest journals. Given the pace of clinical advances, we now know that this alone will not lead to continued mastery. For example, remaining current in the field of internal medicine is estimated to require reading 33 publications a day (Sackett, 2002). The belief that expertise develops as function of time in practice appears to be an outdated notion as well. Recent literature has demonstrated that, in fact, the longer a physician is in practice, the less likely they are to incorporate new evidence-based guidelines in the care of their patients (Choudhry, Fletcher, & Soumerai, 2005). New literature even challenges the paradigm of self-directed learning (Davis et al, 2006; Eva & Regehr, 2005). Like many other people, physicians are notoriously poor at identifying gaps in their understanding or competence. We tend to focus on studying those aspects of medicine that we find most interesting, often subjects that we have already mastered. We are hard wired to avoid content that is difficult or uninteresting to us (Eva & Regehr, 2008).

Experts in continuing medical education have outlined a several-step process, described below, for designing and implementing comprehensive programs to help physicians update their medical knowledge (Hager et al, 2008). Physicians can use this framework to structure their own learning experiences. These steps include recognizing an opportunity or need for learning; searching for resources for learning; engaging in learning; trying out what was learned; and incorporating what was learned into routine practice.

LEARNING EXERCISE 6-1

Reflect on your approach to maintaining professional excellence in the domains of knowledge and clinical problem solving.

What journals do you routinely read? Why? Have they changed over the life of your career? Do you discuss articles with colleagues in a formal way (such as in a journal club)?

How do you decide which articles to read? If you read an article that outlines a different approach to a problem that you see in your practice, how do you decide whether to change your practice based on that study? If you do think that a change in your approach is needed, how would you find the patients in your practice who might benefit from this new approach?

When you are seeing patients during your workday, how often do you look up information while the patient is in the office? What resources do you use when you need to look up something? How do you know that these are trusted resources? What do you do when there are conflicting reports about a given approach?

How often do you read articles that detail new understandings in basic science, such as genomics or systems biology?

Opportunities for learning present themselves when physicians scan journal articles or attend a formal CME course and recognize that new information is available on a clinical topic relevant to their practice. Physicians frequently recognize opportunities for learning in the course of patient care, such as when:

a patient asks a question that the physician cannot answer or brings information from the Internet that the physician has not seen previously;

a patient on usual treatment fails to improve;

a consultant recommends a strategy previously unknown to them;

a patient is doing poorly possibly because of an incorrect initial diagnosis.

An opportunity for learning may also present itself when a performance audit done by the physician on his or her own practice or by an external entity (e.g., a health plan or hospital) demonstrates outcomes that are less than optimal.

Dr. Kevan couldn’t believe what he was seeing. He had passed his surgical boards with flying colors just 5 years ago and now was settled into a wonderful small group practice in a suburb of a large city. He worked hard to stay abreast of the medical literature and practiced diligently in the simulation center of a local medical school to perfect the latest surgical techniques. Despite his personal commitment to excellence, the most recent report on surgical site infections and 30-day readmission rates for his service at the hospital were terrible. His initial reaction was to disregard the results. After all, as one of the youngest surgeons, he took care of more emergency cases and his patients were sicker than everyone else’s. There was really nothing he could do, was there?

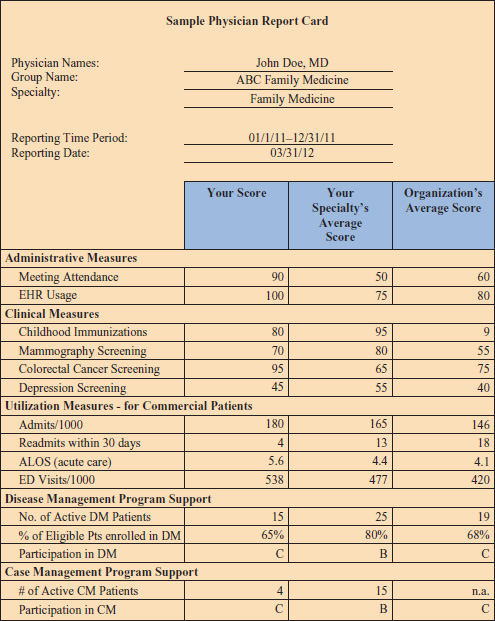

Physician level performance data exist on outcome measures such as patient satisfaction, process measures such as frequency of performing diabetic foot exams, safety measures such as completion of surgical checklists, and complication measures such as wound infections and readmissions. In the preceding example, the surgeon could participate in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) (http://site.acsnsqip.org/). Individual physicians and physician groups are receiving feedback on their performance regularly. For example, a report card for an individual doctor is presented in Figure 6-1. The goal of these report cards is to motivate physicians to work to improve quality.

Although data suggesting that our performance is not as good as we had hoped should be viewed as an opportunity to learn and improve, the reality is many physicians respond defensively at first. Like Dr. Kevan, they may criticize the collection of the data (“They must be including patients seen by residents—my records don’t reflect this level of performance”), or the choice of benchmarks (“It didn’t adjust appropriately for case mix, my patients are sicker”), or the appropriateness of the standards (“I don’t agree with those guidelines”) (Ofri, 2010). Still others warn that measuring and publicizing quality may have unintended consequences, such as encouraging physicians to avoid caring for the sickest patients in an effort to improve their report cards (Ofri, 2010; Werner & Asch, 2005). Although these are important considerations, physicians striving for excellence realize the value of periodic measurement of their performance to help them prioritize and focus on their greatest opportunity for learning.

It is clear that on a given day, there may be dozens of opportunities for physicians to update their knowledge in response to these learning cues. To avoid overlooking a learning opportunity, many now advocate that physicians track these learning cues in a portfolio and periodically check to ensure that they have followed up to learn, at least about some of the questions (D’Alessandro, 2011; Van Tartwijk & Driessen, 2009).

LEARNING EXERCISE 6-2

Have you received any data about your performance as a physician, other than the results of your latest licensing or certifying examination? (If you have not received any performance data, what data would you like to receive? Who should provide it? Can you seek out this information?)

If so, what aspects of your performance were measured? Compliance with administrative policies (such as billing)? Patient volume? Patient satisfaction? Patient access? Compliance with evidence-based guidelines for prevention? Rates of infection?

When you received these data, what surprised you most?

Did you know how to respond if your data were not as good as you hoped they would be?

The widespread availability of web-based resources has made it easier to find resources for learning but more challenging to separate high quality from low quality information. Physicians need to develop a way to recognize the best available evidence for the patient in front of them. Sackett (2002) describes different ways that physicians can carry out this responsibility. Some may choose to identify and personally appraise the quality of the primary literature by conducting a literature review and applying evidence-based medicine quality criteria to the publication. Others may choose to seek out evidence that has been critically evaluated by others with more expertise in critical appraisal by searching for information in reliable evidence-based medicine journals or collections such as The Cochrane Collaboration (http://www.cochrane.org/), BMJ Evidence Centre (), ACP Clinical Practice Guidelines (http://www.acponline.org/clinical_information/guidelines/guidelines/), or UpToDate (http://www.uptodate.com/), or replicate the practice of experts by locating and applying clinical practice guidelines.

Dr. Sarah Parelly was skeptical about clinical practice guidelines until she joined a committee of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) charged with creating a guideline for ablation therapy for atrial fibrillation. She had always thought of guidelines as cookbook medicine or crutches for weak physicians who just didn’t keep up with the literature. But the process the committee engaged in was amazing. They scoured the literature, debated which studies were sufficiently robust to include, and anticipated clinical situations for which the guidelines weren’t appropriate. The process also made her reflect on which aspects of her practice were based on solid evidence and which were based on expert opinion without strong evidence. She thought it might be feasible to build some of the guidelines into her practice’s newly implemented electronic medical record.

In choosing to use literature that has been appraised by others as their strategy for identifying the best evidence, physicians must be sure that the experts upon whom they are relying are truly expert, as free from conflicts of interest as possible, and that the evidence they are recommending is relevant to the patient in front of them. Over the last decade, the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education has worked to ensure that presentations for which CME credit is granted are free from commercial influence (Steinman, Landefeld, & Baron, 2012).

Sometimes the available evidence may not be appropriate for or effective in a given patient. This is when the physician must use his or her understanding of the foundational science to develop a reasoned approach to management. Knowledge of science and evidence also enables the physician to identify and assess or construct different options for care when patients are reluctant or unable to pursue standard treatment. When no conclusive evidence exists to guide the treatment for a particular patient’s condition, physicians should encourage the patient to seek opinions from national experts and to consider participation in reputable clinical trials (Institute of Medicine, 2011).

Engaging in learning is a key element of the continuing education paradigm. Research has consistently shown that interactive learning experiences are much more likely to result in behavior change than are passive experiences like the standard grand rounds lecture (Hager et al, 2008). There are many ways that individual physicians can make their learning interactive. A physician who translates his or her clinical uncertainty about a patient into an answerable evidence-based medicine question and then seeks the answer is creating an interactive learning experience. Other methods including reading material followed by doing multiple choice questions to assess learning, or participating in a webinar and an asynchronous chat group to discuss the application of the presented content. Another alternative is reading and discussing articles and how to apply them to practice with a group of colleagues. All of these methods require interactive learning.

Dr. Robiak has been a practicing gynecologist for 20 years. Over the past year, she has been reading about the advantages of robotic surgery in gynecology and urology. Two months ago, she saw a demonstration at one of the national meetings she regularly attends. The hospital that she admits to has recently purchased a robot for gynecologic procedures. Yesterday, she called her local medical school and found that they would be offering a simulation course in robotic surgery next month. It would require a full week out of the office, but Dr. Robiak feels that she should really practice in a low risk setting to begin to acquire these skills. She knows that one of her community colleagues had a serious complication when he first started using the equipment; she hopes the simulation teaching can help her prevent this.

Excellence is not only relevant to a physician’s knowledge. Physicians must also continuously update their skills as new instruments and techniques replace the clinical and procedural skills they learned as residents. Here, too, advances in education have changed the way we view procedural competency. Rather than relying on the old strategy of “see one, do one, teach one,” we now seek opportunities for physicians to practice and refine new techniques in simulated environments before attempting them on patients. Simulation centers offer active learning opportunities in invasive procedural skills with task trainers and virtual reality programs, and clinical reasoning with sophisticated, physiologically realistic computer mannequins. Specialized centers can offer procedural training using unembalmed cadavers and carefully managed animals. Emerging literature has shown that physicians trained with use of simulation perform better with fewer complications than those trained in the traditional method of practice on patients (Barsuk et al, 2012; Buchs et al, 2013; McGaghie et al, 2011; Wayne et al, 2008). Simulation also offers the opportunity for assessing physician competence when they apply for credentials at a new hospital or for a new procedure. Standardized patients could also be used to help practicing physicians master new patient-centered communication techniques such as shared decision making; however, this is an underutilized strategy in continuing medical education.

Medicine is an applied science. It is not sufficient for a physician to declare that they have learned a new concept—they must apply that new concept in their practice for the benefit of their patients. The first attempts by a physician or group of physicians to implement new information into practice are often challenging, since old habits must be changed. It can be helpful to use decision-support tools such as guidelines embedded into electronic medical records (Ebell, 2010) or cognitive tools such as checklists (Spector et al, 2012; Weiser et al, 2010) to remind physicians of the desired changes. Over time, the frequency of reminders can decrease, as the “new” information becomes the standard operating procedure. Many have found utility in continuing to use these strategies to reinforce critical information, even after the initial period of learning has been completed.

Dr. Smith-Barnes is a hospitalist who recently attended a CME program on basal-bolus management of insulin. When he returned to the hospital, he worked with a local endocrinologist to develop a training program for his colleagues, including the internists and family physicians, to update their knowledge on insulin strategy (many are still using sliding scale insulin). In addition to giving everyone pocket cards to remind them of what they learned, he has worked with the electronic medical records experts in his hospital to replace the old insulin sliding scale orders with a new basal-bolus insulin dose calculator for adult patients.

Dr. Nakano hesitated. One of his long-term patients, Mrs. Johansen had just told him that her son, Jan, had recently been diagnosed with advanced HIV and was coming home to live with her. She asked Dr. Nakano if he would be Jan’s doctor when he moved back. Dr. Nakano had last cared for a patient with HIV infection a decade ago and he hadn’t kept up with the latest antiretroviral agents. He told Mrs. Johansen that he would be willing to continue to provide coordination of care but that it would be important for her son to have the expertise of an HIV specialist to assist. He also said that he would try to update his own knowledge in changes in HIV management so he could support the HIV specialist in implementing appropriate treatments.

Excellence sometimes means admitting that you are not the right physician for a specific patient, even if you have worked hard to remain current in your field. You might be asked to care for a patient with a condition that you do not know how to manage. The patient may need a procedure that, while you could do, you know is done more effectively by one of your colleagues. Alternatively, the patient may need care after you have been up for 24 hours and, although you know the patient, someone who is more rested may make better decisions. It can be difficult to admit your limitation to your patients and let them know that you must refer them to someone with different expertise. Patients may even try to reassure you that you are “good enough” for them and dismiss your concerns that your knowledge and skills may not be ideal for this circumstance. In this situation, living the values of excellence, altruism, and prudence means staying involved with your patient’s care but arranging for someone else to take the lead on directing the optimal care plan, as Dr. Nakano demonstrates in this case.

Striving for excellence also requires the ability to tolerate uncertainty. Rarely will patients present with textbook findings, where everything fits perfectly together. Far more common are situations in which information is incomplete or conflicting, yet one has to make treatment plans and communicate clearly nonetheless. For example, practicing physicians know well the uncertainties that surround prognosis (Smith, White, & Arnold 2013). Even when good data exists (e.g., a given malignancy might have a documented survival rate of 75% at 1 year), there is so much variation that it is often impossible to know if your patient will be in the 75% that lives or the 25% that does not. Even more often, prognostication is difficult as many patients have multiple diseases and conditions, each with their own effects on survival. This degree of uncertainty is very difficult for both patients and physicians to deal with.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree