Patient Story

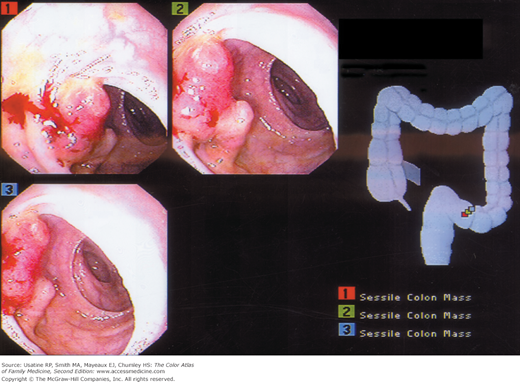

A 72-year-old man reports rectal bleeding with bowel movements over the past several months and the stool seems narrower with occasional diarrhea. He has a history of hemorrhoids but at this time is not experiencing rectal irritation or itching, as with previous episodes. His medical history is significant for controlled hypertension and a remote history of smoking. On digital rectal examination, his stool sample tests positive for blood but anoscopy fails to identify the source of bleeding. On colonoscopy, a mass is seen at 30 cm (Figure 64-1). A biopsy was obtained and pathology confirmed adenocarcinoma.

Introduction

Colon cancer is a malignant neoplasm of the colon, most commonly adenocarcinoma. With the establishment of screening programs and treatment improvements, there has been a slow decline in both the incidence and mortality from colon cancer, although it is still a leading cause of cancer death.1

Epidemiology

- Colon cancer is the third most common cancer in both men and women in the United States, second only to lung cancer as a cause of death.1

- The incidence and mortality have been slowly but steadily declining in the United States for the past decade.2 The American Cancer Society estimated there were 142,570 new cases of colorectal cancer (102,900 colon cancer cases) and 51,370 deaths in 2010.3

- Onset is after age 50 years and peaks at around age 65 years.

- Proximal colon carcinoma rates in blacks are higher than in whites.4

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Colon cancer appears to be a multipathway disease with tumors usually arising from adenomatous polyps or serrated adenomas; mutational events occur within the polyp including activation of oncogenes and loss of tumor-suppressor genes.1,5

- The probability of a polyp undergoing malignant transformation increases for the following cases:1

- The polyp is sessile, especially if villous histology or flat.

- Larger size—Malignant transformation is rare if smaller than 1.5 cm, 2% to 10% if 1.5 to 2.5 cm, and 10% if larger than 2.5 cm.

- The polyp is sessile, especially if villous histology or flat.

- Important genes involved in colon carcinogenesis include adenomatous polyposis gene mutations, KRAS oncogene, chromosome 18 loss of heterozygosity leading to inactivation of SMAD4, and DCC tumor-suppression genes (deleted in colon cancer). Other mutations in genes, such as MSH2, MLH1, and PMS2, result in what is known as high-frequency microsatellite instability (H-MSI), which is found in cases of hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer and in approximately 20% of sporadic colon cancers.4

Risk Factors

- Ingestion of red and processed meat.

- Hereditary syndromes—Polyposis coli and nonpolyposis syndromes (40% lifetime risk).4

- Inflammatory bowel disease.

- Bacteremia with Streptococcus bovis—Increased incidence of occult tumors.

- Following ureterosigmoidostomy procedures (5% to 10% incidence over 30 years).

- Smoking.

- Alcohol consumption.

- Family history of colon cancer in a first-degree relative.

- Obesity.

Diagnosis

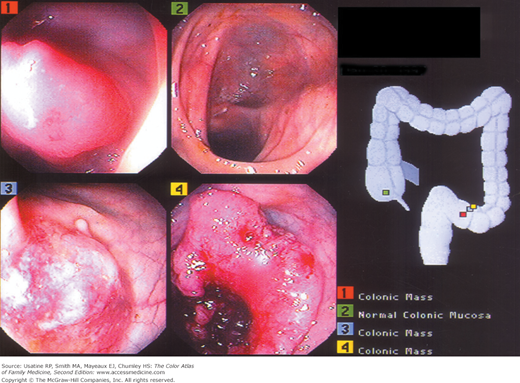

The diagnosis of colon cancer is sometimes made following a positive screening test [i.e., digital rectal examination, fecal occult blood test (FOBT), sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, or barium enema]. For patients who have symptoms and signs suggestive of colon cancer, the confirmative diagnostic test most commonly performed is colonoscopy with biopsy. Colonoscopy allows direct visualization of the lesion, examination of the entire large bowel for synchronous and metachronous lesions, and an ability to obtain tissue for histologic diagnosis.

Symptoms vary, primarily based on anatomic location, as follows:1

- Right-sided colon tumors more commonly ulcerate, occasionally causing anemia without change in stool or bowel habits.

- Tumors in the transverse and descending colon often impede stool passage causing abdominal cramping, occasional obstruction, and rarely perforation (Figure 64-5).

- Tumors in the rectosigmoid region are associated more often with hematochezia, tenesmus (i.e., urgency with a feeling of incomplete evacuation), narrow caliber stool, and uncommonly, anemia.

Physical signs often appear later in the course of the disease and can include:4

- Weight loss and cachexia.

- Abdominal distention, discomfort, or tenderness.

- Abdominal or rectal mass.

- Ascites.

- Rectal bleeding or occult blood on rectal examination.

- Colonoscopy of the entire colon is recommended to identify additional neoplasms or polyps (Figures 64-1 and 64-2).

- Evaluation for metastatic disease includes:8

- Local metastasis: Abdominal/pelvic CT scans.

- Lung metastasis: Chest x-ray or chest CT.

- Liver metastasis: MRI (pelvis), CT (abdomen and pelvis) or positron emission tomography (PET) CT scan (whole body).

- The American College of Radiology also recommends transrectal rectum ultrasound for pretreatment staging for patients with rectal cancer and the addition of MRI of the abdomen for patients with large rectal tumors.9

- Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)—An elevated CEA level can be used to monitor for recurrence. Pretreatment CEA (C-stage) is an independent predictor of overall mortality (60% increased risk) in patients with colon cancer.10 CEA may be elevated for reasons other than colon cancer, such as pancreatic or hepatobiliary disease; elevation does not always reflect cancer or disease recurrence.

- At surgery, surgeons perform an examination of the liver, pelvis, hemidiaphragm, and full length of the colon for evidence of tumor spread.1

- Local metastasis: Abdominal/pelvic CT scans.

Differential Diagnosis

- Inflammatory bowel disease, which includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease (see Chapter 65, Ulcerative Colitis); symptoms include bloody diarrhea, tenesmus, passage of mucus, and cramping abdominal pain. Extraintestinal manifestations, more common in Crohn disease, include skin involvement (e.g., erythema nodosum), rheumatologic symptoms (e.g., peripheral arthritis, symmetric sacroiliitis), and ocular problems (e.g., uveitis, iritis). Diagnosis may be made on the basis of endoscopy.

- Diverticulitis—Patients present with fever, anorexia, lower left-sided abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Abdominal distention and peritonitis may be found on physical examination. Diagnosis is clinical or made on the basis of abdominal CT scan.

- Appendicitis—Initial symptoms include periumbilical or epigastric abdominal pain that over time becomes more severe and localized to the right lower quadrant. Additional symptoms include fever, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia.

Other causes of rectal bleeding:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree