Patient Story

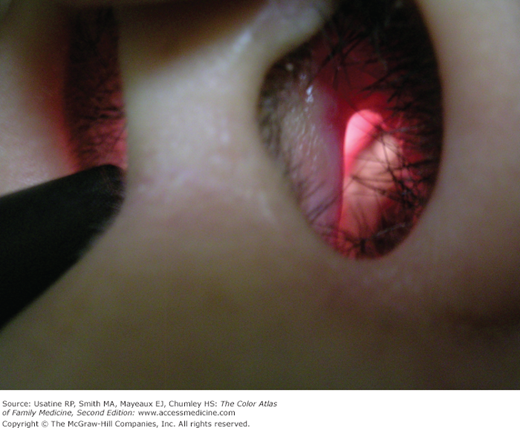

A 26-year-old man is brought into the emergency department in status epilepticus by his “friends,” who promptly flee the scene. His seizures spontaneously cease, and he is noted to have an altered mental status. IV access is obtained and he is stabilized. A urine toxicology screen is positive for cocaine and his creatinine phosphokinase is markedly elevated. He is admitted for cocaine-induced seizures and rhabdomyolysis. He survives the hospitalization and consents to a photograph of his eyes before discharge. Figure 239-1 shows the bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhages that occurred during his seizures. The patient states that he understands the gravity of the situation and will enter a drug rehabilitation program when he leaves the hospital.

Introduction

Cocaine use is common, and 5% to 6% of users develop dependence within the first year of use. Acutely intoxicated patients have increased heart rates, blood pressures, temperatures, and, initially, respiratory rates; mood changes, involuntary movements; and dilated pupils. Chronic addiction can be treated with a comprehensive program, although only one-third of patients will become and remain abstinent.

Epidemiology

- Based on the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) using interviews with a nationally representative sample of 9282 English-speaking respondents ages 18 years and older (conducted in 2001 to 2003), the cumulative incidence of cocaine use was 16%.1

- Similar numbers were reported from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in 2005:2

- Of Americans ages 12 years and older, 13.8% reported lifetime cocaine use in 2005.2

- A total of 33.7 million Americans ages 12 years and older reported lifetime use of cocaine, and 7.9 million reported using crack cocaine.2

- An estimated 2.4 million Americans reported current use of cocaine (682,000 of whom reported using crack).2

- Of the estimated 860,000 new users of cocaine in 2005, most were age 18 years or older, with the average age of first use being 20 years.2

- The percentage of youth ages 12 to 17 years reporting lifetime use of cocaine was 2.3%, and among young adults ages 18 to 25 years the rate was 15.1%.2

- Of Americans ages 12 years and older, 13.8% reported lifetime cocaine use in 2005.2

- For both male and female cocaine users, the estimated risk for developing cocaine dependence, based on data from the NCS-R, was 5% to 6% within the first year after first use.3 Thereafter, the estimated risk decreased from the peak value, with a somewhat faster decline for females in the next 3 years after first use.

- Females may be more susceptible to crack/cocaine dependence; in a study of 152 individuals (37% female) in a residential substance-use treatment program, females evidenced greater use of crack/cocaine (current and lifetime heaviest) and were significantly more likely to show crack/cocaine dependence than males.4

- In one study, siblings of cocaine-dependent individuals had an elevated risk of developing cocaine dependence (relative risk [RR] = 1.71).5

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Cocaine is a stimulant and local anesthetic that causes potent vasoconstriction.

- It produces its stimulant effects by causing increasing synaptic concentration of monoamine neurotransmitters (i.e., dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin).6

- Similar to other local anesthetics, cocaine blocks the generation and conduction of electrical impulses in excitable tissues (e.g., neurons and cardiac muscle) blocking the voltage-gated fast sodium channels in the cell membrane and abolishing the ability of the tissue to generate an action potential.7

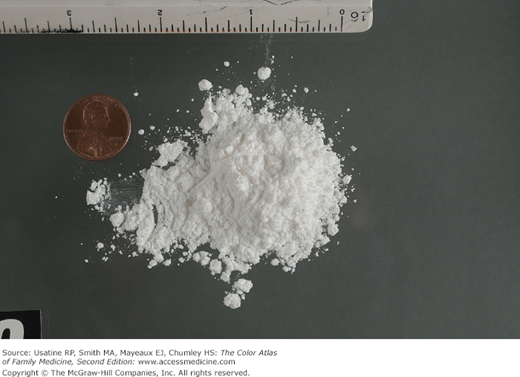

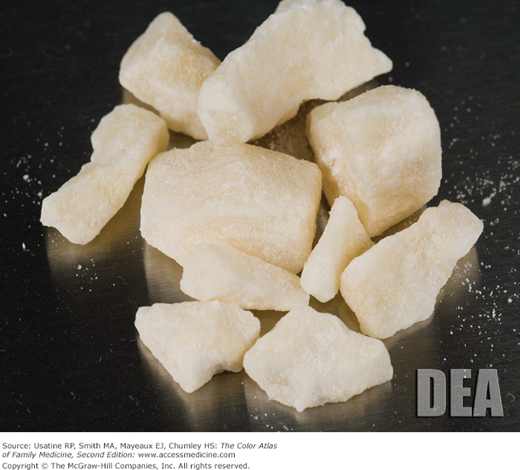

- Effects are seen following oral, intranasal (as a powder [Figure 239-2]), IV, and inhalation administration (as crack cocaine [Figure 239-3], coca paste, and free-base).

Risk Factors

- Family history/genetic predisposition

- In a study of inner-city incarcerated male adolescents (23% of whom had used cocaine or crack in the month before arrest and 32% of whom had used cocaine at least once), current cocaine/crack users were more likely to have the following characteristics:8

- Alcohol, marijuana, and intranasal heroin use.

- Multiple previous arrests.

- To be out of school.

- To be psychologically distressed.

- To have been sexually molested as a child.

- To have substance-abusing parents.

- To have frequent sex with girls, to be gay or bisexual, and to engage in anal intercourse.

- Alcohol, marijuana, and intranasal heroin use.

- Among those who died from an accidental drug overdose in New York City, those dying from cocaine-only versus opiates were more likely to be male, black or Hispanic, have alcohol detected at autopsy, and to be of older age.9

Diagnosis

- Acute effects occur within 3 to 5 minutes with intranasal administration (8 to 10 seconds with free base) and last approximately 1 hour, after which there is an abrupt disappearance of the effects.6 When used IV or smoked as crack cocaine, the onset of action is immediate and the peak effect occurs 3 to 5 minutes later, lasting for 20 to 30 minutes.7

- The acute effects include:6,7

- Elevated heart rate, increased blood pressure, and usually increased temperature.

- Increased respiratory rate and/or dyspnea followed by decreased respiratory rate.

- Mood changes including enhanced mood/euphoria, hyperactivity, irritability and anxiety, excessive talking, and long periods without eating or sleeping.

- Involuntary movements (e.g., tremors, chorea, and dystonic reactions).

- Elevated heart rate, increased blood pressure, and usually increased temperature.

- Additional findings on physical examination can include:

- Dilated pupils, nystagmus, and/or retinal hemorrhages.

- Nasal septum perforation (Figure 239-4), epistaxis, and/or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea.

- Wheezing, rales, and/or pneumothorax.

- Absent bowel sounds (mesenteric ischemia) and/or right upper quadrant tenderness (hepatic necrosis).

- Skin tracks from intravenous use (Figure 239-5).

- Multiple areas of atrophic skin scars are from skin popping—injecting cocaine directly into the skin without finding a vein for intravenous injections (Figure 239-6).

- Dilated pupils, nystagmus, and/or retinal hemorrhages.

- Acute effects may be altered by concomitant use of other drugs or alcohol.

- The acute effects include:6,7

- Adverse effects of cocaine use can include:6

- Respiratory depression that may result in death.

- Cardiac arrhythmias, chest pain, and myocardial infarction (MI).

- Neurologic symptoms, including headache, tonic-clonic seizures, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Myalgias and rhabdomyolysis.

- Severe pulmonary disease (e.g., alveolar hemorrhage and pulmonary edema) and hepatic necrosis caused by crack cocaine.

- Exacerbation of existing hypertension, cardiac, and cerebrovascular disease.

- Recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis.10

- Respiratory depression that may result in death.

- Cutaneous vasculitis secondary to levamisole-adulterated cocaine has been reported many times in the literature.11–15 This type of vasculitis presents with ear purpura (Figure 239-7), retiform (like a net) purpura (Figure 239-8) of the trunk or extremities, neutropenia, and positive tests for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (P-ANCA).11 A 2010 U.S. report found that more than 77% of seized cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.13 This cutaneous vasculitis may also present on the nose or face (Figure 239-9).

- Chronic cocaine use is associated with decreased libido and impaired reproductive function.1

- In men, cocaine can cause impotence and gynecomastia.

- In women, cocaine can cause galactorrhea, amenorrhea, and infertility.

- In pregnant women, crack cocaine is associated with an increase in placental abruption, miscarriage, and congenital malformation.

- In men, cocaine can cause impotence and gynecomastia.

- Protracted use can cause paranoid ideation and visual and auditory hallucinations. Severe depression can follow recovery from cocaine intoxication (called “crashing”).1

- Withdrawal from chronic cocaine use can cause depression, insomnia, and anorexia.