Chapter 22 Clinical reasoning in physiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

This chapter has undergone significant revision since the last edition of this book. We have retained the overview of clinical reasoning in physiotherapy being hypothesis-oriented and collaborative, along with discussion of key factors within the therapist influencing clinical reasoning. To this we have added discussion of the biopsychosocially oriented World Health Organization (WHO) framework of health and disability (WHO 2001) that depicts the scope of knowledge, skills and clinical reasoning focus physiotherapists must have. We present a biopsychosocial, collaborative hypothesis-oriented model of clinical reasoning in practice along with the notion of dialectical reasoning strategies, and a framework of different hypothesis categories that can operate within that model. We contend that these reasoning tools can assist therapists’ application of biopsychosocial theory to practise in the spirit of the WHO framework and provide quality patient-centred physiotherapy services.

SITUATING PHYSIOTHERAPISTS’ CLINICAL REASONING WITHIN A BROADER FRAMEWORK OF HEALTH AND DISABILITY

Whether working with patients having musculoskeletal/sports, neurological, oncological or cardiorespiratory problems from infants through to old age, or working in health promotion/injury prevention, physiotherapists must consider all factors potentially contributing to a person’s health. Although physiotherapists are often perceived as having a focus on the ‘physical’, contemporary biopsychosocial understanding of health and disability (Borrell-Carrió et al 2004) requires that any attention to a patient’s physical health include full consideration of environmental and psychosocial factors that may influence physical health, within the scope and limits of the therapists’ education. This requires a holistic philosophy of health and disability, assessment and management knowledge (including referral pathways) and skills for all potential contributing factors. In addition, clinical reasoning proficiency is required to recognize whether these potential contributing factors are relevant to the individual patient, in order to make appropriate clinical judgements that will contribute to the patient’s optimal health care.

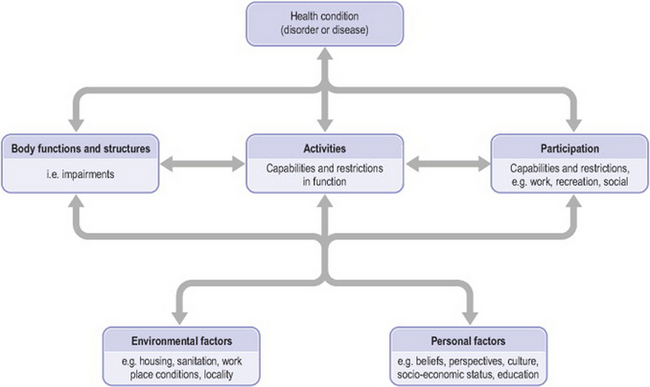

The WHO has published a ‘family’ of international classifications to guide health services, such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO 2001). The ICF provides a standardized language and framework to facilitate communication about health and health care across professional disciplines and sciences. The ICF is based on a WHO framework of health and disability (Figure 22.1) that portrays a person’s functioning and disability as outcomes of interactions between health conditions and contextual factors (both environmental and personal). ‘Functioning’ refers to all body functions, activities (a person’s executions of tasks) and participation (a person’s involvement in life situations such as work, family, leisure). ‘Disability’ is another umbrella term, referring to impairments in body function and structure, activity limitations and participation restrictions.

Figure 22.1 Framework of health and disability (adapted from ‘Interactions between the components of ICF’, World Health Organization 2001, p 18, with permission)

Thus patients’ health conditions can be seen to both influence and be influenced by their body functions and structures (or physical status), their capacity and performance of functional activities of life, and their subsequent ability to participate in their family, work and leisure roles. People’s physical status, activities, participation and health condition can be positively or negatively influenced by a variety of factors, including environmental factors (e.g. social attitudes, architectural characteristics, legal and social structures, climate, terrain) and personal factors (e.g. gender, age, psychological features such as thoughts/beliefs, feelings and coping styles, health and illness behaviours, social circumstances, education, past and current experiences). This framework provides an excellent contextualization for physiotherapy practice.

THE CLINICAL REASONING PROCESS IN PHYSIOTHERAPY: HYPOTHESIS-ORIENTED AND COLLABORATIVE

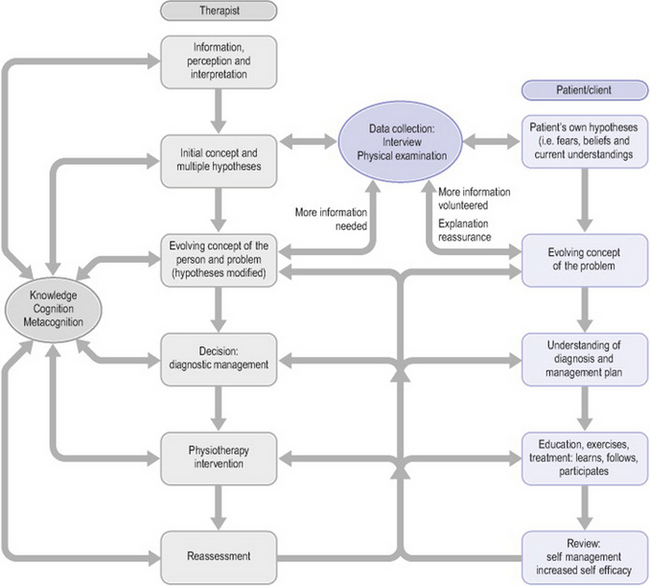

Understanding the clinical reasoning underlying a physiotherapist’s assessment and management of a patient requires consideration of the thinking process of the therapist, the patient and the shared decision making between the two. Figure 22.2 presents a biopsychosocial model of clinical reasoning as a collaborative process between physiotherapists and patients (Edwards & Jones 1995). In all physiotherapy settings, the physiotherapist’s reasoning begins with the initial data/cues obtained (e.g. referral, observation of the patient). This preliminary information will evoke a range of impressions or working interpretations. While typically not thought of as such, they can be considered hypotheses in the sense that these initial interpretations are not fixed, final decisions. Instead, they are considered against subsequent information (data) obtained that may support or not support the initial impressions. Although this is similar to a process of hypothesis testing, depending on their education, not all therapists will be cognisant of this process, or indeed of their reasoning in general. Hypothesis generation involves a combination of specific data interpretations or inductions and the synthesis of multiple clues or deductions. In most settings the initial hypotheses are quite broad, for example in an outpatient setting: ‘looks like a back or hip problem’. Initial hypotheses may be physical, psychological or socially related, with or without a ‘diagnostic’ implication.

Figure 22.2 Biopsychosocial model of clinical reasoning as a collaborative process between physiotherapists and patients (adapted from Edwards & Jones 1995, with permission)

Equally important to the therapist’s thinking are patients’ thoughts about their problems, as reflected in the boxes on the right side of Figure 22.2. That is, patients begin their encounter with a physiotherapist with their own ideas of the nature of their problem, as shaped by personal experience and advice from medical practitioners, family and friends. Patients’ understanding of their clinical problem has been shown to impact on their levels of pain tolerance, disability and eventual outcome (Flor & Turk 2006, Jones & Edwards 2006). Patients’ beliefs and feelings which are counterproductive to their management and recovery can contribute to lack of involvement in the management process, poor self-efficacy and, ultimately, to a poor outcome. Conversely, patients who have been given an opportunity to share in the decision making have been shown to take greater responsibility for their own management and to have a greater likelihood of achieving better outcomes (Edwards et al 2004b). Patients’ self-efficacy and the responsibility they take for their management can be maximized through a collaborative reasoning process with their therapists.

Through a process of evaluating patients’ understanding of and feelings about their problems, through explanation, reassurance and shared decision making, patient and therapist jointly develop an evolving understanding of the problem and its management. Responsibility is shared between patient and therapist, with the patient taking an active role in the management.

KEY FACTORS INFLUENCING CLINICAL REASONING

Clinical reasoning is influenced by factors relating to the specific task, the setting, the patient or client and the decision maker. For purposes of this discussion, we highlight certain critical aspects of those factors pertaining to the decision maker. The box to the left in Figure 22.2 highlights the strong relationship of the clinician’s knowledge, cognition and metacognition within the process of clinical reasoning. Double-headed arrows are used to convey that these factors influence all aspects of the clinical reasoning process and in turn are strengthened by clinical reasoning experience, particularly when clinicians think or reflect about what they do during and after a clinical encounter.

KNOWLEDGE

Clinical reasoning requires rich organization of a wide range of knowledge including scientific and professional theory, procedural know-how and personal philosophy of practice, values and ethics. The importance of knowledge to physiotherapists’ clinical reasoning is highlighted in Jensen’s expertise research, in which expert physiotherapists were seen to possess a broad, multidimensional knowledge base acquired through professional education and reflective practice where both patients and colleagues were valued as sources of learning (Jensen et al 2000). Physiotherapists utilize various forms of knowledge in their clinical reasoning including propositional (‘knowing that’) and non-propositional (‘knowing how’) knowledge (see Higgs & Titchen 2000, and Chapter 11). Identifying the use of these different types of knowledge in clinical practice reflects the tension between clinical reasoning that is focused on the clinical aspect of patient care and that kind of decision making that is identified in the current imperative for practitioners to serve as moral agents in assisting patients to negotiate the demands of increasingly complex healthcare systems (Nelson 2005).

COGNITIVE AND METACOGNITIVE SKILLS

Therapists’ analysis of patients’ presentations occurs at varying levels of complexity. Single bits of information that are perceived as potentially relevant (e.g. patients’ description of symptoms, activity or participation restrictions, or understanding and expectations) must be understood in their own right, often requiring further clarification and ‘validation’ with the patient. Then, at a higher level of complexity, separate bits of information must be synthesized into a larger analysis of their meaning. In this way the addition of new information often alters a previous working interpretation. For example, on its own, tenderness to palpation and pain with physical testing may implicate specific somatic tissues. However, when these findings are considered alongside a long history of impairments and disability with what appear to be significant influences from psychosocial factors, the same physical signs may warrant an alternative interpretation such as central sensitization-induced mechanical hyperalgesia (Meyer et al 2006).

This synthesis of patient information is a form of pattern recognition. In both everyday life and in physiotherapy practice, knowledge is stored in our memory in chunks or patterns that facilitate more efficient communication and thinking (Anderson 1990, Rumelhart & Ortony 1977, Schön 1983). These patterns are prototypes in memory of frequently experienced situations that individuals use to recognize and interpret other situations. In physiotherapy, patterns exist not only in classic diagnostic syndromes and associated management strategies, but also in the pathobiological mechanisms associated with those syndromes and the multitude of environmental, physical, psychological, social and cultural factors that contribute to the development and maintenance of patients’ problems. Physiotherapists must be able to recognize patterns of biomedical factors that contraindicate physiotherapy as clinical ‘red flags’ suggesting the presence of potentially serious organic pathology (Roberts 2000) and a range of psychosocial factors (conceptualized by the notion of yellow, blue and black flags (Kendall et al 1997, Main & Burton 2000, Main et al 2000)) that may predispose to chronic pain, prolonged loss of work and serve as potential obstacles to recovery.

Pattern recognition is required to generate hypotheses, and hypothesis testing provides the means by which those patterns are refined, proved reliable and new patterns are learned (Barrows & Feltovich 1987). Although expert therapists are able to function largely via pattern recognition, novices who lack sufficient knowledge and experience to recognize clinical patterns will rely on the slower hypothesis-testing approach to work through a problem. However, when confronted with a complex, unfamiliar problem, experts, like novices, will rely more on the hypothesis-oriented method of clinical reasoning (Barrows & Feltovich 1987, Patel & Groen 1991).

Physiotherapists are constantly faced with alternative choices of assessment, interpretation, and management action, the decisions about which may relate to their ability to synthesize the multitude of information obtained about a patient’s presentation and the weighting they have given (consciously or unconsciously) to the various findings. Since therapists’ cognition (perceptions, interpretations, synthesis and weighting of information) is directly related to their knowledge, faulty knowledge or personal biases and habits of practice can lead to errors in reasoning. Similarly, despite pattern recognition being a mode of thinking used by experts in all professions of life (Schön 1983), it also represents perhaps the greatest source of errors in our thinking (see Chapter 1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree