Chapter 1 Clinical decision making and multiple problem spaces

In the second edition of this book we drew on our initial view of clinical reasoning as a process incorporating the elements of cognition, knowledge and metacognition, expanding this to place a greater emphasis on patient-centred care as the context for clinical reasoning. Practitioners were presented as interactional professionals (Higgs & Hunt 1999) whose effectiveness required interaction with their immediate and larger work environment, with the key players in that context, and with the situational elements pertinent to the patient and case under consideration. Health care was presented via a social ecology model as occurring within the wider sphere of social responsibility of professionals which requires practitioners to be proactive as well as responsive to changes in healthcare contexts (Higgs et al 1999).

In this opening chapter of the third edition we extend our previous examination of the nature of clinical reasoning and its context, drawing on our own research and that of colleagues and co-authors. We expand our interpretation of clinical reasoning from a process view, to explore clinical reasoning as a contextualized phenomenon (see also Chapters 2, 8). We extend consideration of the decision-making context from a focus on the immediate task environment of case management acting in the wider healthcare context to explore the multiple levels of the clinical decision-making space, or rather the multiple decision-making spaces, within which interactive reasoning and decision making occur (see Higgs 2006a, b).

In relation to clinical reasoning expertise, we extend the notion of an expert to encompasscapability, professional artistry and patient-centredness; expertise is a journey rather than a point of arrival (see also Chapters 11 and 16). In examining and making explicit these aspects of clinical reasoning our goal is to make clinical reasoning more accessible for novices to learn, for experienced practitioners to portray, for educators to teach, for clinicians to practise and for researchers to explore.

UNDERSTANDING CLINICAL REASONING

In the 10 years since we produced the first edition of this book, we have retained our view that clinical reasoning is both simple and complex. Simply, clinical reasoning is the sum of the thinking and decision-making processes associated with clinical practice; it is a critical skill in the health professions, central to the practice of professional autonomy, and it enables practitioners to take ‘wise’ action, meaning taking the best judged action in a specific context (Cervero 1988, Harris 1993). Despite being straightforward and ‘simple’ this view is very broad; clinical reasoning is seen as permeating throughout clinical practice and as being the core of practice. The importance of understanding the complex nature of clinical reasoning is emphasized in the goal of developing tolerance of ambiguity and a reflexive understanding of practice artistry during health sciences education, as suggested by Bleakley et al (2003).

The complex view of clinical reasoning is embedded in its simplicity and breadth (Higgs 2006b). By encompassing so much of what it means to be a professional (autonomy, responsibility, accountability and decision making in conditions of uncertainty), clinical reasoning gains an inherent mystique. This complexity lies in the very nature of the task or challenge, faced by novice and expert alike, which is to process multiple variables, contemplate the various priorities of competing healthcare needs, negotiate the interests of different participants in the decision-making process, inform all decisions and actions with advanced practice knowledge, and make all decisions and actions in the context of professional ethics and community expectations. The mystique is most evident in the skill of the expert diagnostician who makes difficult decisions with seeming effortlessness, and in the professional artistry of the experienced practitioner who produces an individually tailored health management plan that addresses complicated health needs with humanity and finesse. To address and achieve these professional attributes clinical reasoning is much more a lived phenomenon, an experience, a way of being and a chosen model of practising than it is simply a process. To this end we adopt the following definition of this complex phenomenon:

Clinical reasoning (or practice decision making) is a context-dependent way of thinking and decision making in professional practice to guide practice actions. It involves the construction of narratives to make sense of the multiple factors and interests pertaining to the current reasoning task. It occurs within a set of problem spaces informed by the practitioner’s unique frames of reference, workplace context and practice models, as well as by the patient’s or client’s contexts. It utilises core dimensions of practice knowledge, reasoning and metacognition and draws on these capacities in others. Decision making within clinical reasoning occurs at micro, macro and meta levels and may be individually or collaboratively conducted. It involves metaskills of critical conversations, knowledge generation, practice model authenticity and reflexivity. (Higgs 2006b)

CLINICAL REASONING AND METASKILLS

Our previous model of clinical reasoning (Higgs & Jones 2000) was presented as an upward and outward spiral, a cyclical and a developing process. Each loop of the spiral incorporated data input, data interpretation (or reinterpretation) and problem formulation (or reformulation) to achieve a progressively broader and deeper understanding of the clinical problem. Based on this deepeningunderstanding, decisions are made concerning intervention, and actions are taken. The process was described as including:

To these dimensions we now add four meta-skills:

It is preferable to view clinical reasoning as a contextualized interactive phenomenon rather than a specific process. The practitioner responsible for making the decisions interacts both with the task and informational elements of decision making and with the human elements and interests of other participants in the decision making. Such interactions can be called critical creative conversations that involve interactions based on critical appraisal of circumstances and, where possible, critical interests in promoting emancipatory practice, and the creation and implementation of particularized, person-centred healthcare programmes (Higgs 2006a).

THE ADEQUACY OF DIFFERENT INTERPRETATIONS

THE NATURE OF CLINICAL REASONING AS A PHENOMENON

Consider the real world of clinical decision making. Orasanu & Connolly (1993) have described the characteristics of decision making in dynamic settings as follows:

To work within this practice world we need an approach to clinical reasoning that accommodates these complexities. Higgs and colleagues (2006, p. l) described a number of key characteristics of clinical reasoning as follows:

DIFFERENT INTERPRETATIONS OF CLINICAL REASONING

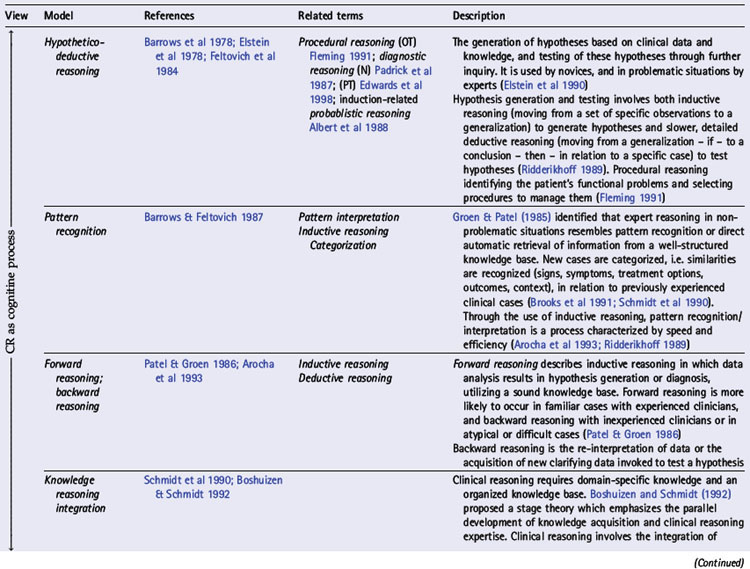

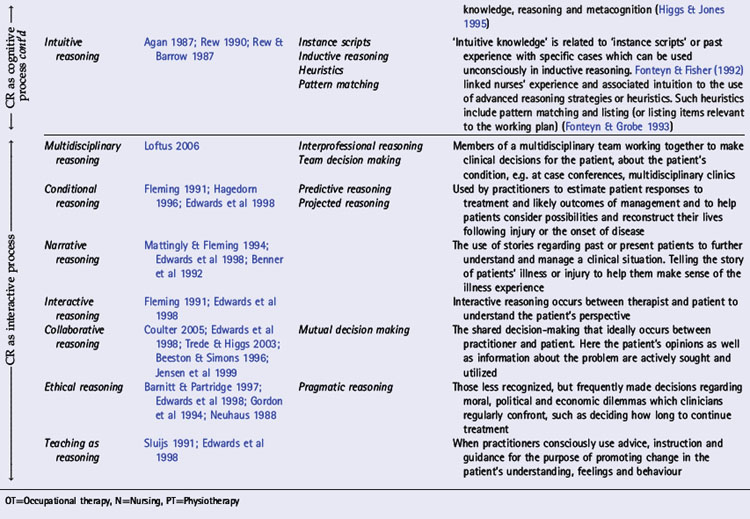

In various chapters of this book a number of interpretations of clinical reasoning are discussed from the perspective of different disciplines, the history of clinical reasoning research, and models of practice within which clinical reasoning occurs. In Table 1.1 we present an overview of key models,strategies and interpretations of clinical reasoning. These have been divided into two groups: cognitive and interactive models. This division reflects three trends: changes in the focus of research and theoretical understandings of clinical reasoning (see Chapters 18, 19); changes in society and expectations of health care (see Chapter 2); and a major shift in emphasis (as outlined above) from the second to the third edition of this book.

Expertise and clinical reasoning

In a review of clinical reasoning literature in medicine, Norman (2005) suggested that there may not be a single representation of clinical reasoning expertise or a single correct way to solve a problem. He noted that ‘the more one studies the clinical expert, the more one marvels at the complex and multidimensional components of knowledge and skill that she or he brings to bear on the problem, and the amazing adaptability she must possess to achieve the goal of effective care’ (p. 426).

Clinical reasoning and clinical practice expertise is a journey, an aspiration and a commitment to achieving the best practice that one can provide. Rather than being a point of arrival, complacency and lack of questioning by self or others, expertise requires both the capacity to recognize one’s limitations and practice capabilities and the ability to pursue professional development in a spirit of self-critique. And it is – or at least we should expect it to be – not only a self-referenced level of capability or mode of practice, but also a search for understanding of and realization of the standards and expectations set by the community being served and the profession and service organization being represented. Box 1.1 presents these characteristics and expectations of experts.