10.1 HISTORY OF VIRUS CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE

Virologists are no different to other scientists in that they find it useful to classify the objects of their study into groups and subgroups. In the early days, when little was known about viruses, they were loosely grouped on the basis of criteria such as the type of host, the type of disease caused by infection, and whether the virus is transmitted by an arthropod vector.

As more was learned about the characteristics of virus particles some of these began to be used for the purposes of classification, for example:

- whether the nucleic acid is DNA or RNA;

- whether the nucleic acid is single-stranded or double-stranded;

- whether or not the genome is segmented;

- the size of the virion;

- whether the capsid has helical symmetry or icosahedral symmetry;

- whether the virion is naked or enveloped.

Various combinations of these criteria produced some useful virus groups, but there was no single approach to the naming of the groups, and names were derived in a variety of ways:

- small, icosahedral, single-stranded DNA viruses of animals were called parvoviruses (Latin parvus = small);

- nematode-transmitted polyhedral (icosahedral) viruses of plants were called nepoviruses;

- phages T2, T4, and T6 were called T even phages.

Serological relationships between viruses were investigated, and distinct strains (serotypes) could be distinguished in tests using antisera against purified virions. Serotypes reflect differences in virus proteins and have been found for many types of virus, including rotaviruses and foot and mouth disease virus.

10.1.1 International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

By 1966 it was decided that some order had to be brought to the business of naming viruses and classifying them into groups, and the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) was formed. The committee now has many working groups and is advised by virologists around the world.

The ICTV lays down the rules for the nomenclature and classification of viruses, and it considers proposals for new taxonomic groups and virus names. Those that are approved are published in book form (please see Sources of further information at the end of this chapter) and on the web; these sources should be consulted for definitive information. The web site for this book (www.wiley.com/go/carter) has links to relevant web sites.

10.2 MODERN VIRUS CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE

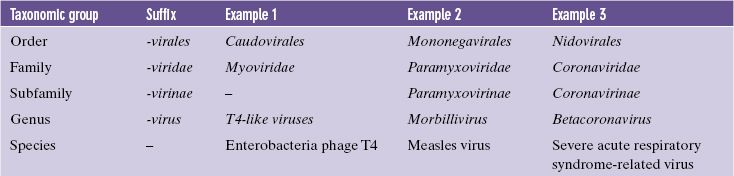

For a long time virologists were reluctant to use the taxonomic groups such as family, subfamily, genus, and species that have long been used to classify living organisms, but taxonomic groups of viruses have gradually been accepted and are now established (Table 10.1). Some virus families have been grouped into orders, but higher taxonomic groupings, such as class and phylum, are not used. Only some virus families are divided into subfamilies.

Table 10.1 Taxonomic groups of viruses

Each order, family, subfamily, and genus is defined by viral characteristics that are necessary for membership of that group, whereas members of a species have characteristics in common but no one characteristic is essential for membership of the species. Many species contain variants known as virus strains, serotypes (differences are detected by differences in antigens), or genotypes (differences are detected by differences in genome sequence).

Many of the early names of virus groups were used to form the names of families and genera, e.g. the picornaviruses became the family Picornaviridae. Each taxonomic group has its own suffix and the formal names are printed in italic with the first letter in upper case (Table 10.1), e.g. the genus Morbillivirus. When common names are used, however, they are not in italic and the first letter is in lower case (unless it is the first word of a sentence), e.g. the morbilliviruses.

10.2.1 Classification based on genome sequences

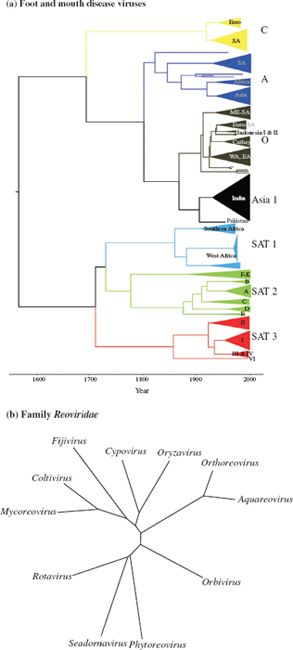

Now that technologies for sequencing virus genomes and for determining genome organization are readily available, the modern approach to virus classification is based on comparisons of genome sequences and organizations. The degree of similarity between virus genomes can be assessed using computer programs, and can be represented in diagrams known as phylogenetic trees because they show the likely phylogeny (evolutionary development) of the viruses. Phylogenetic trees may be of various types (Figure 10.1):

Figure 10.1 Phylogenetic trees. (a) Rooted tree showing relationships between foot and mouth disease virus serotypes based on VP1 sequences. The serotypes evolved in different regions of the world. (b) Unrooted tree showing relationships between genera in the family Reoviridae based on VP1 sequences.

Source: (a) Tully and Fares (2008) Virology, 382, 250. Reproduced by permission of Elsevier.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree