19 Chronic Disease Prevention

I Overview of Chronic Disease

Not directly transmissible person to person

Not directly transmissible person to person

Routinely span years and often decades

Routinely span years and often decades

Degenerative in some way, relating to aberrant or declining function of some body part or system

Degenerative in some way, relating to aberrant or declining function of some body part or system

Often propagated by fundamental physiologic imbalances or disturbances, such as inflammation

Often propagated by fundamental physiologic imbalances or disturbances, such as inflammation

A The Human Toll

A short list of chronic diseases—heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and chronic lung disease—constitute the leading force of worldwide mortality. More than 60% of all deaths in the world each year are attributable to this short list of conditions.1

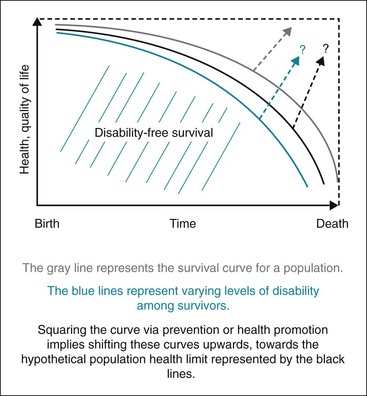

In some ways, the mortality toll of chronic diseases can exaggerate their harms. Chronic degeneration of vitality and function is, to one degree or another, the human fate until such time as the “rectangularization” of the mortality curve can be converted from an aspiration to prevailing reality2 (Fig. 19-1). As life expectancy rises, so does the opportunity for time-dependent degeneration of organ systems. Chronic, degenerative disease is simply a point along this spectrum and thus inescapable under prevailing conditions if persons live long enough; we must eventually die of something. To the extent chronic disease merely represents this inevitable “something,” the attributed death toll can make the situation seem worse than the reality. Not succumbing to infectious or traumatic causes of death early in life partly makes us vulnerable to chronic diseases later. The importance of causes of death earlier in life is best captured not by the number of deaths but by the number of years of potential life lost (see Chapter 24).

Figure 19-1 The concept of rectangularizing, or squaring, the survival curve.

(From Society, the individual, and medicine, Ottawa, Canada, 2010, University of Ottawa. www.med.uottawa.ca/sim/data/Rectangularization_of_mortality_e.htm)

In another important way, however, the mortality toll of chronic diseases greatly underestimates the human cost. Long before taking years from life by causing premature death, chronic diseases take life from years by reducing ability, function, vitality, and quality. This is an ever more salient concern because chronic diseases, driven largely by a short list of lifestyle factors and particularly their relationship to obesity,3 occur at ever younger ages. What was called only a generation ago “adult-onset diabetes” is now called type 2 diabetes and routinely diagnosed in children. The proliferation of cardiac risk factors in ever younger children is well documented.4 Further, the occasional lifestyle-related cancer is diagnosed in surprisingly younger persons. A marked increase in the rate of stroke among children age 5 to 14 years also has been reported.5

Collectively, these trends indicate the importance of factoring the chronicity of chronic disease into any assessment of the human cost. As serious and potentially disabling disease begins at ever-younger ages, mortality becomes an increasingly less useful measure of the total impact of these conditions. A measure of attenuated quality of life, adjusted for the life span affected, is most suitable6 (See Chapters 14 and 24 for quality-adjusted life years [QALY] and disability-adjusted life years [DALY]). By such a metric, the human cost of chronic disease is enormous, and it continues to rise.

B The Financial Toll

There are glib expressions in the halls of medicine about the relative financial costs of life and death. Death is, in financial terms, inexpensive as expenditures related to treatment and preservation of life cease. Life, burdened by chronic disease, can be enormously expensive. As we grow ever more adept at forestalling death through the application of pharmacotherapy, procedures, and medical technology, the costs of living with chronic disease are rising. In the United States, more than 75% of Medicare expenditure (hundreds of billions of dollars annually) is for chronic disease.7

Other messages related to the financial costs of chronic disease are decidedly less positive. As addressed later, chronic diseases are substantially preventable by means already available. The reliance on high-cost treatment is to some degree testimony to the failure to make better use of lower-cost prevention. There is also widespread failure to treat risk factors such as high blood pressure and dyslipidemia to target levels.8,9

Also, the direct financial costs of chronic disease care do not fully capture the economic toll. Reduced productivity, absenteeism, presenteeism (attending work while sick), and related effects, known in economic terms as externalities or indirect costs (or benefits; externalities can be positive as well as negative), are high and may even exceed the direct costs.10

Projections about the financial costs of chronic disease are genuinely alarming and constitute nothing less than a crisis, questioning the fundamental solvency and economic viability of the U.S. health care system beyond the middle of the 21st century should current trends persist. As a result, there is increasing awareness about the importance of chronic disease prevention and the strategies that will convert what is known in this area into what is done, as well as increased attention to better management of chronic disease with patient-centered medical homes11 and the chronic care model.12 Professionals directly involved in public health and preventive medicine have a clear opportunity to advance the mission of prevention in responding to the dangers of the chronic disease crisis.

C Common Elements in Pathogenesis

There is increasing appreciation for a unifying constellation of processes that underlie most if not all chronic degenerative diseases.13,14 These pathways and their details will spawn discussion and debate for years. A case may be made, however, for a short list of common pathways, as shown in Box 19-1.

Box 19-1 Four Pathophysiologic Pathways in Chronic Disease*

Of particular relevance in the context of epidemiology is that a common constellation of factors underlying most or all chronic diseases suggests the presence of common pathways to prevention as well. This indeed appears to be the case; the same short list of lifestyle factors appears to influence the likelihood of all major chronic diseases across the life span, other factors being equal (see Box 19-2). The notion of common pathways to diverse morbidities has been embraced by leading health agencies15 and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).16

Box 19-2 Ten Controllable Factors in Prevention of Chronic Disease

| Tobacco | Toxic agents |

| Diet | Firearms |

| Activity patterns | Sexual behavior |

| Alcohol | Motor vehicles |

| Microbial agents | Drug use |

Modified from McGinnis JM, Foege WH: JAMA 270:2207–2212, 1993.

II Preventability of Chronic Disease

Literature spanning at least the past two decades makes a compelling case that the leading causes of premature death—and thus the leading causes of chronic morbidity, because they are the same—are overwhelmingly preventable by means already available. A seminal 1993 paper first highlighted that chronic diseases leading to premature death were not meaningfully “causes” of death but rather “effects.”17 These effects—the chronic diseases—were the result of 10 factors, mostly behaviors that individuals can control (Box 19-2). Using the epidemiology of 1990, this analysis found that about 80% of all premature deaths were attributable to the first three entries: tobacco, diet, and activity patterns (physical activity). Alliteratively, the leading causes of chronic disease and premature death in 1990 were “how we used our feet, our forks, and our fingers.”

In 2004 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated and supported the same fundamental conclusions.18 The same is true of subsequent related studies.19–21 In addition, recent and accumulating evidence indicates that lifestyle interventions can modify gene expression and thus alter the risk for chronic disease development and progression at the genetic level.22,23 In the aggregate, this literature belies the importance of the nature/nurture debate by highlighting the hegemony of “epigenetics” and the apparent human potential to “nurture nature.”

The available data from diverse sources suggest that about 80% of all chronic disease could be prevented. With regard to specific conditions, 80% or more of cardiovascular disease; 90% or more of diabetes; and as much as 60% of cancer are thought to be preventable with the use of resources already available. Were this knowledge to be translated into the power of routine action, it would increase life expectancy and add much more to health expectancy, or the “health span.”24 In blunt terms, if and when we find the means to turn what we know about the prevention of chronic disease into what we routinely do, it would constitute one of the most stunning advances in the history of public health (see Chapter 28).

III Condition-Specific Prevention

A Obesity

Of perhaps more direct practical importance is that the identification of obesity as a disease facilitates its inclusion among conditions with medical insurance coverage. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) coding system used for billing third-party payers assigns a “diagnostic code” to any given condition. Obesity must be recognized among candidate conditions for such coverage to be processed. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services initially designated obesity as a disease with this in mind, and relevant progress has followed. In 2011 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) authorized reimbursement for obesity counseling to physicians treating patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or greater25 (Table 19-1).

Table 19-1 Classification of Weight Status Based on Body Mass Index (BMI)

| BMI* | Classification |

|---|---|

| <18 | Underweight |

| 18-25 | Normal weight |

| 25-29.9 | Overweight |

| 30-34.9 | Stage I obesity |

| 35-39.9 | Stage II obesity |

| >40 | Stage III (severe) obesity |

*Expressed as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (weight [kg]/height2 [m]).

Throughout most of human history, calories have been relatively scarce and often difficult to obtain, and physical activity has been an unavoidable requirement for survival. Modern society has devised an environment in which physical activity is scarce and often difficult to maintain, and calories are unavoidable. Homo sapiens are endowed with no native defenses against caloric excess and the tendency toward “sedentariness.” The result is the modern obesity trends. In essence, the population is confronting an environment for which it is poorly suited and is succumbing to its toxic effects. We are drowning in calories. This perspective might promote an emphasis on environmentally based approaches (policies and programs that facilitate healthful eating and routine physical activity) to obesity prevention and control, even while establishing the medical legitimacy of obesity as a condition deserving treatment (Box 19-3).