Chest Wall Resection and Reconstruction for Advanced/Recurrent Carcinoma of the Breast

Kirby I. Bland

R. Jobe Fix

Robert J. Cerfolio

The incidence of local–regional recurrence following breast conservation surgery or mastectomy varies between 5% and 40%. The probability of recurrence depends upon the presenting pathobiological characteristics of the primary neoplasm and/or the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) clinical tumor stage. Currently, no international standards for local recurrence have been fully defined, but, typically, the combination of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and/or targeted immunotherapy is directed for principal control. Following local–regional recurrence that defines a clinical and radiographically resectable tumor, protocol will typically embrace resection with pathologically negative margins followed by subsequent radiation therapy; many clinics will also utilize hormone-receptor markers (ER, PR, and HER2/neu status) to assist in therapeutic guidance.

For many clinics internationally, despite curability with isolated metastases, chest wall recurrences are left untreated. In contradistinction, while resection of chest wall metastases related to breast carcinoma or other primary neoplasms (e.g., melanoma and sarcoma) may be therapeutically achievable, such recurrences cannot be completed with curative intent. Previous surgical dogma suggesting that chest wall recurrences are the “harbinger of systemic disease” does not necessarily apply when the patient has been fully staged clinically and radiographically and only the isolated breast cancer recurrence is evident.

Preoperative Planning

We have previously published guidelines at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for resection of the chest wall in patients presenting with recurrence/advanced disease related to breast carcinoma.

The indications for operation, as discussed, pertain only to an isolated chest wall recurrence/advanced disease that can be surgically managed with curative intent.

Individuals who have locally confined disease, with requirement of palliation for pain and/or nonhealing/ulcerative lesions related to postirradiation injury with pathologically negative ulcerative sites are included in this group.

It is incumbent upon the oncologic surgeon involved in the care of the patient to establish that there is absence of systemic disease and to exclude multifocally recurrent sites that are being considered for resection.

Relative contraindications that one would consider include advancing age, short disease-free interval of recurrent disease, diminished pulmonary reserve, biopsy-proven extrathoracic disease, and existing systemic comorbidities (e.g., cardiac and endocrine).

Contemporary radiographic imaging is essential for all patients being considered for full-thickness chest wall resection and reconstruction. To properly evaluate chest wall anatomy and extent of tumor progression, we advocate dedicated chest wall magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography (CT) angiography as standard imaging modalities. Standard CT scanning with intravenous contrast also provides invaluable information. Many medical oncologists also consider positron emission tomography (PET) as a definitive test, but coexisting inflammatory sites, especially ulceration sites, with the associated false-positive and false-negative features of PET, do not allow use of this procedure as an exclusive screening modality. However, it is extremely useful in evaluating systemic disease. Evidence of extensive direct lung invasion and pleural effusion are absolute contraindications for consideration of chest wall resection.

The principal site of focally recurrent disease typically presents between the third and sixth rib interspaces; however, the recurrence location, as well as history of the patient’s operative procedure, is paramount.

Review of the surgical history is essential, especially if a transverse or vertical rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM) pedicle flap is being considered with prior abdominal operations, as the same will often affect the flap choice for defect coverage.

The most versatile and most commonly used flap is the latissimus dorsi pedicle flap. Ideally, flaps from previously irradiated fields should be avoided when possible.

Resection that extends beyond four ribs will routinely require rigid chest wall reconstruction. This maneuver constitutes the creation of mesh with polypropylene that may be used as a singular sheet or with creation of a mesh “sandwiched” together with methyl methacrylate. Myocutaneous flaps should be liberally used to cover these reconstructions. When defects are small and there is less probability for creation of the flail defect of the chest wall, mesh alone may be sufficient with this smaller area for coverage.

Preoperative planning between the surgical oncologist and reconstructive surgeons, following discussion with the medical oncologist, should define the indications, relative merits, and technical approaches essential for full oncologic resection (Table 1).

Surgery Positioning and Incisions

Following patient intubation with a double-lumen, endotracheal tube, the patient is positioned in the supine or lateral decubitus position depending upon the planned resection of the local recurrence and flap choice. An appropriately sized double-lumen, endotracheal tube should be selected. The area for harvest of the potential skin flap and graft-donor sites should also be prepped and draped into the operative field.

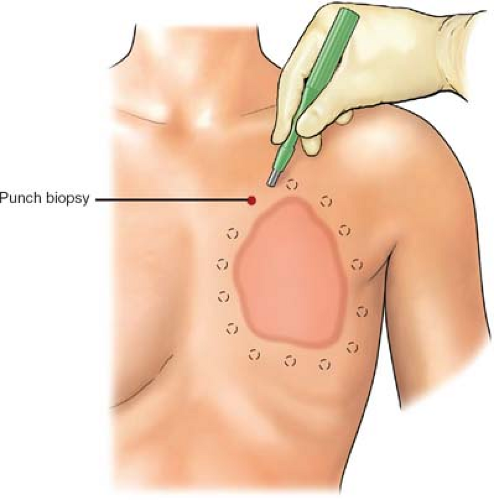

Preferentially, we prefer a minimal 2-cm margin developed 360 degrees around the periphery of the planned resection area (Fig. 1). It is critical that both the oncological surgeon and the plastic surgeon plan the operative incision prior to skin incision, estimating the maximum cephalad, caudad, medial, and lateral extent of the tumor, such that the estimate for margins of resection can be discussed with the patient and family prior to the planned resection. Such estimates are simultaneously planned with radiographic imaging, if necessary.

Margins should extend a minimal one intercostal space above and below the tumor mass inclusive of the cephalad–caudad aspect of the planned rib resections.

Circumferential full-thickness skin punch biopsies (6 mm) should be sent for frozen section analysis following skin prep and induction. These biopsies will validate a negative pathological margin prior to incision (Fig. 1). Once negative margins are confirmed with pathology, the extent of the incision through the skin overlying the pectoralis major muscle may be completed using cold blade and, thereafter, electrocautery for subcutaneous and muscular tissues.

Table 1 Preoperative Considerations | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Technique of Resection

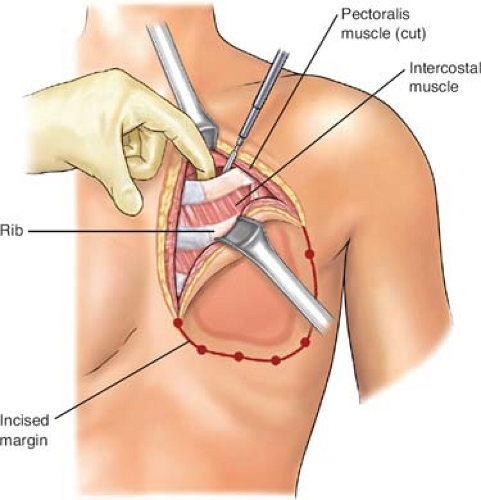

The pectoralis major and minor are incised outside the tumor-bearing area to the level of the chest wall; all ribs for planned resection are medially and laterally exposed. The incision will include all previous punch

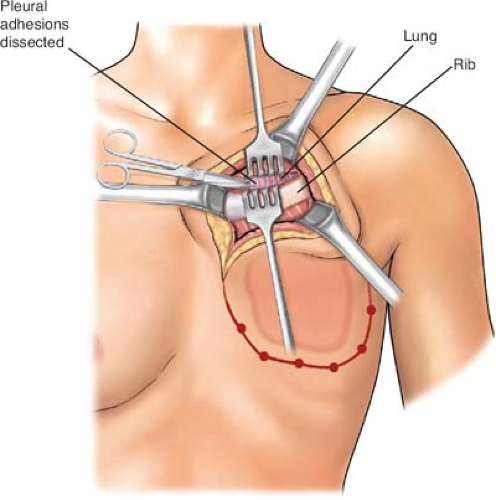

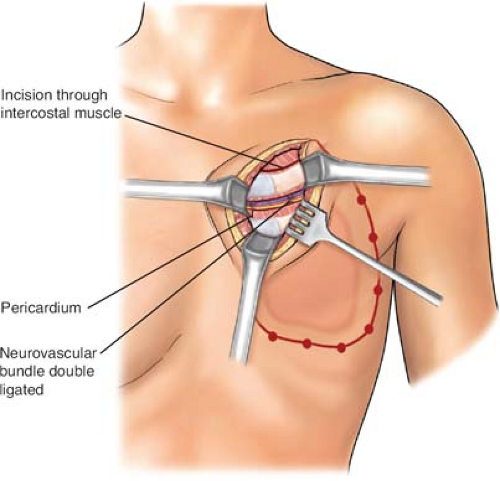

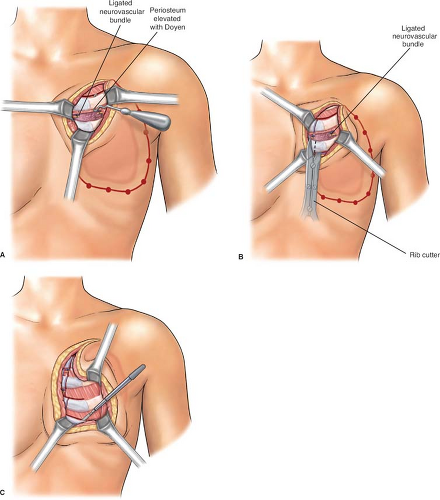

biopsied areas. In the cephalad-most extent of the planned rib resection, the rib is incised on its cephalad surface, and the ipsilateral lung is deflated by the anesthesiologist at the instruction of the surgeon. The thoracotomy should be initiated via the superior margin of the planned resection (Fig. 2). Upon entering the thorax, previous pleural adhesions created by prior radiation therapy and/or surgery should be sharply dissected and mobilized. Attention must be directed to avoidance of injury to the parietal pleura and inadvertent damage to the pulmonary parenchyma. When dissection is incomplete or inadequate, lysis of adhesions should be completed and performed with sharp dissection to avoid the formation of an alveolar–pleural fistula. With dense adhesions related to tumor invasion of the parietal pleura of the lung, complete pleurectomy with simultaneous segmental resection of the focally involved lung segment may be necessary. Repair of any parenchymal tears may be completed by stapling or suturing with a 3-0 absorbable polypropylene suture after adequate deflation of the lung without injury. The incision is thereafter extended around the peripheral margins of the tumor mass through the intercostal muscles (Figs. 3 to 6). The surgeon must be cognizant of ligation of the intercostal neurovascular bundles on the inferior margins of the rib with 2-0 silk suture ligatures (Fig. 5).

biopsied areas. In the cephalad-most extent of the planned rib resection, the rib is incised on its cephalad surface, and the ipsilateral lung is deflated by the anesthesiologist at the instruction of the surgeon. The thoracotomy should be initiated via the superior margin of the planned resection (Fig. 2). Upon entering the thorax, previous pleural adhesions created by prior radiation therapy and/or surgery should be sharply dissected and mobilized. Attention must be directed to avoidance of injury to the parietal pleura and inadvertent damage to the pulmonary parenchyma. When dissection is incomplete or inadequate, lysis of adhesions should be completed and performed with sharp dissection to avoid the formation of an alveolar–pleural fistula. With dense adhesions related to tumor invasion of the parietal pleura of the lung, complete pleurectomy with simultaneous segmental resection of the focally involved lung segment may be necessary. Repair of any parenchymal tears may be completed by stapling or suturing with a 3-0 absorbable polypropylene suture after adequate deflation of the lung without injury. The incision is thereafter extended around the peripheral margins of the tumor mass through the intercostal muscles (Figs. 3 to 6). The surgeon must be cognizant of ligation of the intercostal neurovascular bundles on the inferior margins of the rib with 2-0 silk suture ligatures (Fig. 5).

As the incision is extended around the margins of the resection, the periosteum of the rib should be elevated with a Doyen retractor followed by a periosteal elevator prior to initiating rib division with a rib cutter (Fig. 5A). Following completion of the entire incision, the surgeon should be cognizant about including all the punch biopsy sites to ensure negative surgical margin.

When the tumor margin extends medially to the sternum, it may be necessary to utilize a sternal saw or osteotome to create a partial sternotomy up to and inclusive of the biopsied skin that establishes a clear surgical margin. Moreover, the incision should be extended to the sternocostal margin where the internal mammary artery (IMA) can be palpated, ligated, and divided. The sternum thereafter may be partially resected, but diligence must be exercised to protect the pericardium, which may be centrally adherent to the investing parietal pleura of the sternum, secondary to irradiation.

In all circumstances, the specimen should be resected en bloc, thus exposing the chest wall defect with the exposed,

inflated, protuberant lung. Insufflation of the underlying lung following resection of tumor invasion requires visualization of alveolar–parenchymal leak; repair must be instituted for closure of such leaks. If in-vasive disease is detected grossly or with biopsy, the well-exposed lung can then be managed by a wedge resection of the involved lung with a stapler. Leaking defects should again be oversewn and tested for air leaks prior to tube placement and chest closure (Fig. 6).

inflated, protuberant lung. Insufflation of the underlying lung following resection of tumor invasion requires visualization of alveolar–parenchymal leak; repair must be instituted for closure of such leaks. If in-vasive disease is detected grossly or with biopsy, the well-exposed lung can then be managed by a wedge resection of the involved lung with a stapler. Leaking defects should again be oversewn and tested for air leaks prior to tube placement and chest closure (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. A: Isolation and ligation of both medial and lateral neurovascular bundles. B: Division of rib on its medial surface with rib cutter. C: Further extension of the medial cut with rib cutter to the third rib on its medial surface. (From Bland KI, Fix RJ, Cerfolio RJ. Chest wall resection and reconstruction for advanced/recurrent carcinoma of the breast. In: Bland KI, Klimberg VS, eds. Master techniques in general surgery: breast surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|