2 Chemistry of essential oils

Introduction

For the optimum practice of aromatherapy it is desirable to have at least a basic understanding of the chemistry of the essential oils so as to select their use in a safer, more effective way – not randomly or indiscriminately. Such understanding reveals that while isolated chemicals have certain effects, there is no simple relationship between the effects of isolated components and the effects of the synergistic totality of the complete oil. These complex relationships are little understood because hundreds, even thousands, of different chemical compounds are involved, and many of them are unidentified. Until such time as more is discovered about the interaction of the plant chemicals within the human body, suffice it to say that knowledge of the basic composition of each oil contributes to the overall knowledge of aromatherapists, thereby promoting confidence and aiding selection of the oils to be used. Adams and Taylor (2010) write that ‘based on the wealth of existing chemical and biological data on the constituents of essential oils and similar data on essential oils themselves, it is possible to validate a constituent based safety evaluation of an essential oil. Fundamentally it is the interaction between one or more molecules in the natural product and macromolecules (proteins, enzymes, etc.) that yield the biological response’. In order to reap the benefits of essential oils it is not essential to know chemistry, but some understanding of their composition will enable more effective use, and often a little knowledge of chemistry will enable aromatherapists to respond to health professionals with a technical background who will inevitably pose questions.

Terpene compounds

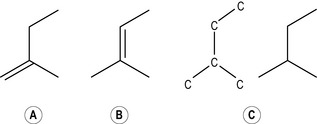

All terpenes are hydrocarbons that consist only of carbon and hydrogen atoms, and they are almost always easily recognizable from their name: all end in -ene. Terpenes, so named by Kekulé because of their occurrence in turpentine oil (Kubecka 2010), are hydrocarbons arranged in a chain, which can be either straight, perhaps with branches, or cyclic. Within the plant, the starting point for the terpenes is acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl coA) from which is formed six-carbon mevalonic acid. This is then modified to the five-carbon unit commonly known as the isoprene unit (Fig. 2.1), which occurs in two unsaturated forms: IPP (isopentenyl pyrophosphate) (Fig. 2.1a) and DMAPP (dimethylallyl pyrophosphate) (Fig. 2.1b). This isoprene unit comprised of five carbon atoms does not exist on its own but is the basic building block for terpenes and is shown diagrammatically as a saturated chain (Fig. 2.1c) for the sake of simplicity, as used later in the book, but it must be borne in mind that it is in fact unsaturated.

Monoterpenes

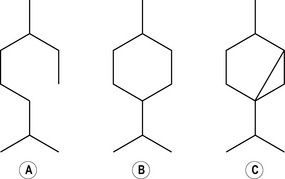

Two isoprene units joined together head to tail form the basis of all monoterpenes (therefore monoterpene hydrocarbons have 10 carbon atoms arranged in a chain) (Fig. 2.2a). Sometimes a chain can, as it were, loop round on itself (Fig. 2.2b) and give the appearance of a ring, although it is still a 10-carbon chain. When this looping occurs, the terpene is said to be monocyclic, because one circle has been created, and therefore the complete description is monocyclic monoterpene. More than one circle can arise in a chain, so that it is possible to have bicyclic and tricyclic monoterpenes. If they do not form a circle at all (i.e. if they form a straight chain) they are said to be acyclic (as in Fig. 2.2a). Not enough is yet understood about the pharmacological effects of these compounds in essential oils in order to know how these variations in structure may modify the effect. Further complexity arises when double bonds are added (by oxidation) or subtracted (by reduction).

Effects of monoterpenes

They are all slightly antiseptic, bactericidal, and may also be analgesic, expectorant and stimulating (Franchomme & Pénoël 2001 pp. 239-244, Roulier 1990 p. 51), and they may also play an important part in the quenching effect mentioned earlier, thus making fragrance quality oils which have had the terpenes partially or totally removed (deterpenated oils) unsuitable for aromatherapeutic purposes.

The limonene found in citrus oils quenches the skin-irritant properties of the citrals, as can readily be seen by the fact that deterpenized lemon oil is four or five times as irritant to the skin as whole lemon oil; others are recently thought to be possible antitumour agents, some stimulate the circulation, etc., and it is undeniable that pine oils, with their rich content of terpenes, are good as air antiseptics, etc.; moreover pine oils appear to have a hormone-like effect on the suprarenal glands. The aromatic monoterpene p-cymene occurs in numerous essential oils and is known to be analgesic on the skin. The essential oil of Cupressus sempervirens, which may be up to 70% monoterpenes, is an anti-inflammatory agent by immunomodulating action (Franchomme & Pénoël 2001 p. 243).

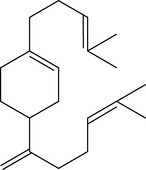

Sesquiterpenes

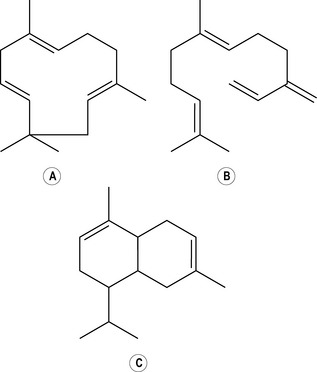

Three isoprene units provide the basic structure for the larger molecules known as sesquiterpenes (sesquiterpene hydrocarbons have 15 carbon atoms) (Fig. 2.3).

Diterpenes

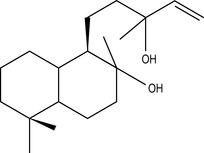

Four isoprene units joined together are called diterpenes (diterpenic hydrocarbons have 20 carbon atoms) (Fig. 2.4), and are not often met with in steam-distilled oils because they are almost too heavy to come over in the distillation process – only a very few manage it.

Figure 2.4 • Diterpenes: four isoprene units join to form a diterpene. This figure shows a monocyclic diterpene (α-camphorene).

Therapeutic effects

In the chemical ‘families’ discussed below, some of the general therapeutic properties attributed to each of the families are based on a theory (set out in detail in Franchomme & Pénoël 2001 pp. 107–131) which associates certain properties with the esters, alcohols, etc., taking into account the electronegative/-positive nature of the molecules coupled with their polar/apolar properties. Although this information is a useful general guide to the probable properties of the chemical families discussed, the information given does not hold true for each and every compound (e.g. alcohols are given the familial characteristic of being stimulating, but the alcohol linalool shows as a sedative – see Table 4.9 – when tested on mice, although the results obtained in animal testing do not necessarily extrapolate directly to humans). In any case, aromatherapists do not use isolated compounds but whole essential oils, and although it is both important and interesting to study the effects of single compounds, it is worth repeating the statement made above that there is not necessarily any simple direct relationship between the therapeutic effect of any one constituent and that of the whole essential oil.

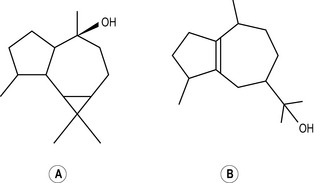

Alcohols

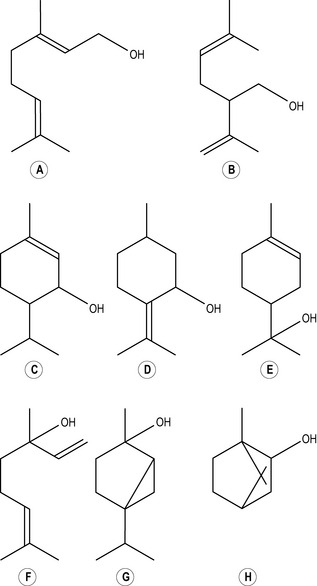

When a hydroxyl group (or hydroxyl radical as it is sometimes called) consisting of one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom ( OH) joins on to one of the carbons in a chain by displacing one of the hydrogen molecules, an alcohol (Figs 2.5, 2.6, 2.7) is formed: a monoterpenic alcohol, sesquiterpenic alcohol or diterpenic alcohol, depending on whether the chain to which it attaches itself has two, three or four isoprene units. The name of the alcohol so formed always ends in -ol, e.g. geraniol. There are alternative names which are in current use for these alcohols: monoterpenic alcohol is also called monoterpenol, sesquiterpenic alcohol is known also as sesquiterpenol and diterpenic alcohol as diterpenol and also diol.

OH) joins on to one of the carbons in a chain by displacing one of the hydrogen molecules, an alcohol (Figs 2.5, 2.6, 2.7) is formed: a monoterpenic alcohol, sesquiterpenic alcohol or diterpenic alcohol, depending on whether the chain to which it attaches itself has two, three or four isoprene units. The name of the alcohol so formed always ends in -ol, e.g. geraniol. There are alternative names which are in current use for these alcohols: monoterpenic alcohol is also called monoterpenol, sesquiterpenic alcohol is known also as sesquiterpenol and diterpenic alcohol as diterpenol and also diol.

Effects of alcohols

Alcohols as a group are anti-infectious, strongly bactericidal, and antiviral as well as being stimulating to the immune system; they are generally non-toxic in use and do not cause skin irritation (Roulier 1990 p. 53). The thujanol-4 molecule is a liver stimulant, as is menthol. Some of the heavier alcohols appear to have a balancing effect on the hormonal system, e.g. the diterpenic alcohol sclareol in Salvia sclarea [clary], as does the sesquiterpenic alcohol viridiflorol in Melaleuca viridiflora [niaouli]: borneol is given as a cholagogue and analgesic, cedrol is phlebotonic and spathulenol is fungicidal – as is sclareol (Beckstrom-Sternberg & Duke 1996 pp. 384, 416, Franchomme & Pénoël 2001 pp. 133, 135).