Cervical Glandular Neoplasia

Preinvasive Glandular Lesions

Terminology

In keeping with the terminology used for squamous cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), earlier investigators recognized three grades of cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia (CGIN),1 but this has proven unrealistic. Three grades (glandular atypia, glandular dysplasia, and atypical hyperplasia), with only subtle differences among them, are not reproducible, and far less so than for corresponding squamous lesions. Even squamous intraepithelial lesions, in the Bethesda System, for example, are grouped into two categories for this reason.2 A more practical approach is to divide the spectrum of glandular changes into two grades. These are variously referred to as low-grade CGIN and high-grade CGIN, or endocervical glandular dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS).3

The 2003 World Health Organization (WHO) classification included, among the precursors of invasive cervical adenocarcinoma, glandular dysplasia and AIS; however, their morphologic distinction remains unclear.4 Endocervical glandular dysplasia (atypical hyperplasia) refers to ‘glandular lesions characterized by significant nuclear abnormalities that are more striking than those in glandular atypia but fall short of the criteria for adenocarcinoma in situ.’4 In other words, glandular dysplasia closely resembles AIS but differs in that the nuclei are not cytologically malignant and mitoses are less numerous. However, because of its rarity, the lack of diagnostic reproducibility, and the uncommon coexistence with AIS, the clinical and biologic significance of glandular dysplasia has not been established.5 Among the biomarkers used to clarify the relationship between glandular dysplasia and AIS are p16INK4A, Ki-67/MIB1, and human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA determination, but results have been controversial.6–8 Besides, the relationship of HPV infection to glandular precursors differs from that of HPV and squamous precursor lesions. Whereas productive HPV infection is represented morphologically by low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL; mild dysplasia), a comparable lesion does not occur in glandular epithelium. Thus, it appears that productive HPV infection is closely associated with squamous but not glandular epithelium. Rather than using the term glandular dysplasia, it has been recommended to evaluate the atypical glandular lesions that fall short of AIS with p16INK4A and Ki-67/MIB1.6,7 Lesions negative for p16INK4A and showing a low Ki-67/MIB1 proliferation index should be diagnosed as reparative changes; on the other hand, lesions expressing a strong and diffuse p16INK4A immunoreaction and a high Ki-67/MIB1 labeling index should be classified as AIS.

Adenocarcinoma In Situ

Etiology

The evidence in favor of AIS being a precursor lesion for invasive adenocarcinoma includes the following: (1) patients with AIS are about 10–15 years younger than those with invasive adenocarcinoma, (2) AIS is commonly found in the vicinity of invasive adenocarcinoma, (3) similar HPV types are identified in both AIS and invasive adenocarcinoma,11 and (4) occasional cases of AIS have been documented to progress to adenocarcinoma.12

General Features

AIS represents 10–20% of cervical adenocarcinomas.13 Compared to high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs), AIS is much less common, with reported ratios varying from 1 : 26 to 1 : 237.14,15 In the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry, of 121,793 (82%) cervical lesions classified as in situ, 120,317 (99%) were squamous cell carcinoma in situ (CIS) and only 1476 (1%) were AIS.14 In contrast to squamous cervical lesions, the incidence of invasive glandular lesions is higher than that of noninvasive glandular lesions.16 The median age at diagnosis in a recent large series was 35 years compared with 41 years for women with invasive adenocarcinoma.17 Most AIS are asymptomatic and found in patients with abnormal cervical smears. AIS does not produce a grossly visible lesion, nor does it have a characteristic lesion like SIL by colposcopy. It involves both the surface and glands of the transformation zone in 65% of cases and is predominantly unifocal.13,18 It can extend for a distance of up to 3 cm into the endocervical canal.18 SIL or invasive squamous cell carcinoma coexists with AIS in 24–75% of cases and the exfoliated atypical cells lead to clinical investigation helping to identify AIS.19 Most AIS are associated with HPV DNA and HPV 16 and 18 are the most commonly encountered types.20

Pathology

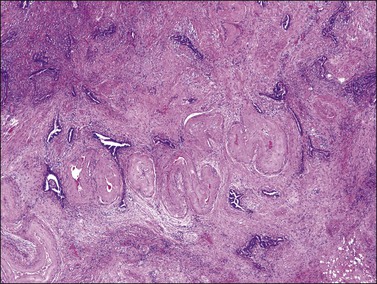

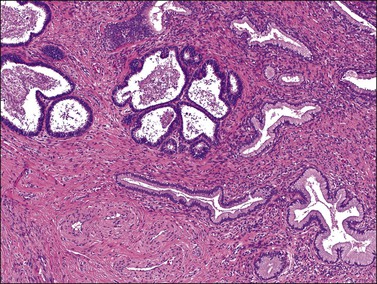

Microscopically, AIS spreads along the surface of the endocervix and does not extend below normal glands. There is neither stromal invasion nor desmoplasia. Part or all of the epithelium lining the glands shows nuclear stratification with elongated, cigar-shaped, hyperchromatic nuclei and increased mitotic activity. Based on cytoplasmic features, four subtypes of AIS have been described: (1) endocervical or mucinous type, (2) intestinal type, (3) endometrioid type, and (4) adenosquamous type. In addition, rare examples of clear cell21 and tubal type have been described. Although these histologic types do not have biologic significance, their distinction helps the pathologist to recognize AIS.

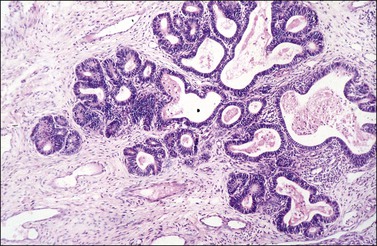

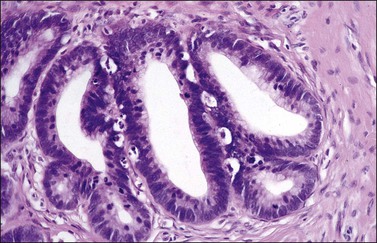

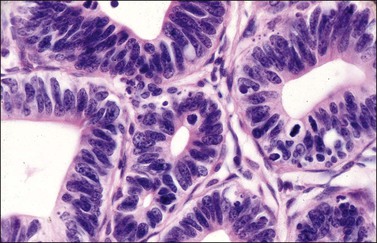

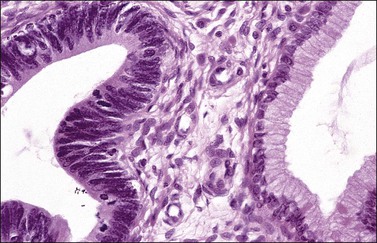

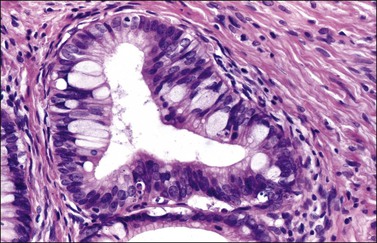

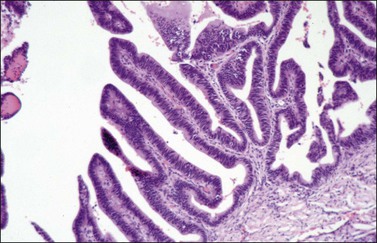

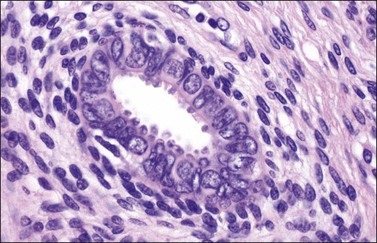

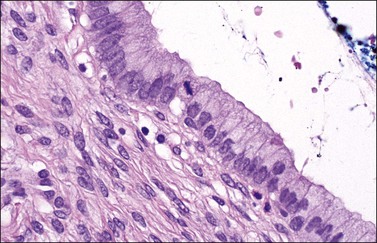

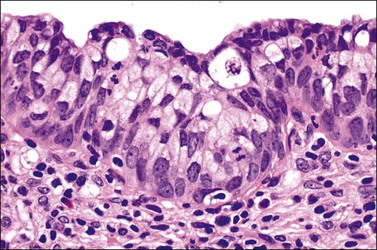

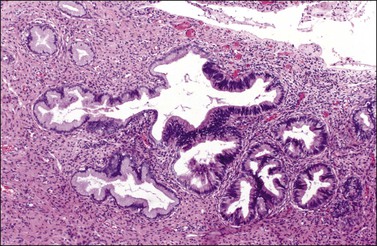

The most common form of AIS is the endocervical type,22 in which the cells resemble those of the endocervix, and glands show nuclear pseudostratification, nuclear atypia, small to moderate amounts of juxtaluminal cytoplasm containing mucin, scattered juxtaluminal mitoses (normal and/or abnormal), and apoptotic bodies (Figures 12.1–12.5).22, 23 Typically, there is a sharp demarcation of AIS from closely uninvolved glands and from the uninvolved epithelium of the same gland (Figure 12.6). The glands of AIS can show numerous outpouchings and complex papillary infoldings and may exhibit a cribriform pattern. Intestinal-type AIS, a form of intestinal metaplasia, is characterized by the presence of goblet cells (Figure 12.7). Occasionally, neuroendocrine cells, which are argentaffin positive, and even Paneth cells may also be present.22 Nuclear atypia is not as evident because the mucin globules compress the nuclei, reducing the degree of nuclear enlargement and pseudostratification. Endometrioid AIS is characterized by glands resembling proliferative or hyperplastic endometrium and exhibits marked nuclear pseudostratification and absent cytoplasmic mucin or mucin staining confined to the luminal border.22 In many ways, this distinction between endocervical and endometrioid AIS is artificial as the endometrioid features represent endocervical-type cells that have lost their intracytoplasmic mucin. Endometrioid AIS is most distinctive when it exhibits villoglandular architecture (Figure 12.8). The adenosquamous type is characterized by glands containing cells exhibiting both glandular and squamous features. It is important to distinguish adenosquamous CIS from AIS, which coexists but is separate from an adjacent HSIL. The tubal type of AIS is diagnostically challenging because of its similarity to tubal metaplasia, but the cells have pseudostratification, nuclear enlargement, coarse chromatin, apoptotic bodies, and mitotic figures.

Figure 12.1 AIS compared with normal glands. The glands involved by AIS show little mucin in comparison to normal endocervical glands.

Figure 12.6 AIS. Sharp demarcation from closely uninvolved glands and from the uninvolved epithelium of the same gland.

Immunohistochemistry

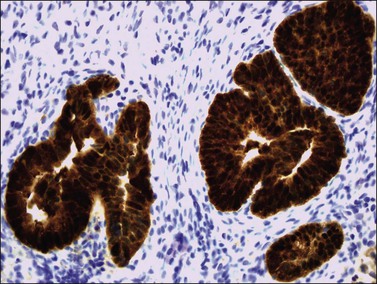

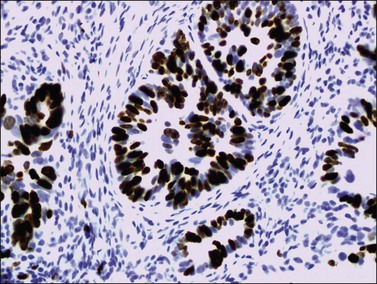

Most cases of AIS show diffuse nuclear and/or cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for p16INK4A (Figure 12.9) whereas normal endocervix demonstrates no reactivity.24 Overexpression of p16INK4A is induced when high-risk HPV DNA integrates into the cell genome. Another useful marker is Ki-67/MIB1. The majority of AIS cells exhibit nuclear reactivity for Ki-67 and the proliferation index is usually over 30% (Figure 12.10).25 In contrast, p53 is expressed only focally in 20% of cases.26 In fact, a strong p53 reaction should alert the possibility of serous carcinoma, either extending from the endometrium or as a primary endocervical tumor. Since AIS typically shows significant degrees of apoptosis, the anti-apoptotic marker bcl-2 is usually negative or only focally positive.25,26 Possibly, Ki-67/MIB1, p16INK4A, and bcl-2 may serve as a diagnostic panel.25 Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) immunoreactivity occurs in 63–78% of AIS cases,27,28 whereas the endocervical epithelium is either negative or shows only luminal reaction. Vimentin immunostaining is negative. As indicated earlier, accurate application of these markers may clarify whether an atypical glandular lesion is a reparative condition or a precursor to endocervical glandular malignancy. Moreover, while these ancillary tests are useful, the mainstay of diagnosis should be careful morphologic examination.25

Cytologic Findings

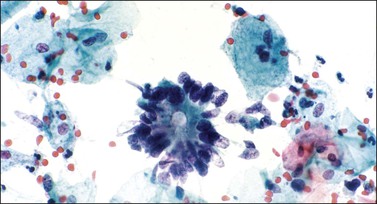

Cytologic ability to detect cervical glandular lesions is limited by both sampling and interpretation. The historical view that the Pap smear has low sensitivity for AIS is changing.29 While relevant studies are few, emerging evidence indicates that the sensitivity of the cervical smear for detecting AIS is in the range of 40–69%.29–32 This compares favorably with sensitivity for CIN 3, which has been reported as ranging between 43% and 75%.31 In the 2001 Bethesda System ‘AIS’ became a separate category.2 Cases showing some features suggestive but not diagnostic of AIS are ‘atypical endocervical cells, favor neoplastic.’ The lowest reporting category for abnormal endocervical cells is ‘atypical endocervical cells, NOS’ (not otherwise specified). Typical architectural features include crowded sheets of columnar cells with palisading and feathering of nuclei at group edges, pseudostratification, small strip-off sheets, and gland openings within the sheets (Figure 12.11). In addition, rosettes are also a characteristic feature (Figure 12.12). The nuclei are typically enlarged and oval shaped with coarse granular chromatin. Mitoses and apoptosis are helpful features if seen. With the use of liquid-based cytology (LBC), the cytologic appearances are different. Glandular groups with this methodology are more three-dimensional than with the usual cervical smear and show attenuation of several typical architectural features of AIS. Nuclear features are better preserved in samples collected in fluid medium.33,34 An advantage of this new methodology is the opportunity to perform immunohistochemical stains, such as p16INK4A on the original cytology samples.24,35

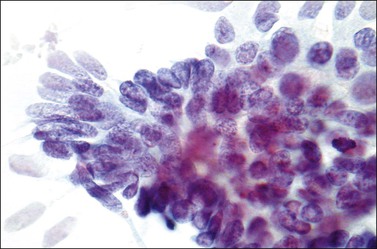

Figure 12.11 AIS, endocervical type (Pap smear). A crowded sheet with ragged edges. Hyperchromatic elongated nuclei show palisading and feathering at the edges of the sheet.

Differential Diagnosis

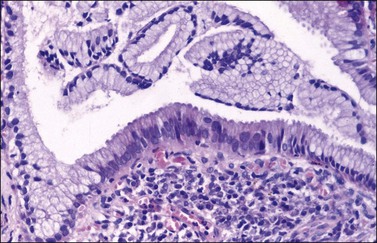

Several benign glandular lesions simulate AIS. The most common is tubal metaplasia, which displays in varying proportions a mixture of ciliated, secretory, and resting (intercalary or peg) cells, even within a single case (Figure 12.13). Glands exhibiting tubal metaplasia lack nuclear atypia and mitoses are seen only occasionally. Apoptotic bodies are inconspicuous. The glands may be associated with endometrioid-type stroma. Endometrioid metaplasia also shows bland nuclei that lack significant mitotic activity. CD10-positive endometrioid stroma may also be present. Immunohistochemically, tuboendometrioid metaplasia shows a low Ki-67/MIB1 immunoreactivity and strong widespread reaction for bcl-2.25,26 It also exhibits p16INK4A in 62% of cases, but, unlike AIS, the reactivity is only focal.25 Tuboendometrioid metaplasia may show reactivity for CEA in 39% of cases, but, unlike AIS, expresses vimentin.27 The presence of cilia usually implies a benign process, but, of note, ciliated AIS also occurs.36

Superficial cervical endometriosis (Figure 12.14) may be confused with AIS histologically, particularly in patients followed with cytologic smears after cone biopsy.37 The endometriotic foci are usually confined to the inner third of the cervical wall. The endometrioid glands are typically evenly spaced, show bland cytologic features, and are surrounded, at least focally, by endometrial-type stroma, which may show focal hemosiderin deposition. Inflammation and hemorrhage may obscure the stromal cells. Mitotic figures are seen in 37% of cases.37

Endocervical glands may show a variety of architectural and cytologic changes in response to inflammation. This may lead to a suspicion of AIS. In inflammatory/reparative changes, the nuclei become enlarged and show chromatin clearing and prominent nucleoli. Nuclear pleomorphism may occur, but the chromatin is often smudged (Figure 12.15). Pseudostratification and mitotic activity are minimal. Apoptotic bodies are generally absent. p16INK4A and Ki-67/MIB1 immunoreactions are usually negative. Endocervical glands in some patients may also show mild morphologic changes during the menstrual cycle. Occasionally, a normal-appearing mitosis can be found in normal endocervical glands and should not raise concern (Figure 12.16).

Radiation therapy results in widely spaced endocervical glands that are often dilated and lined by cells showing nuclear enlargement and pleomorphism, but the cytoplasm is finely vacuolated or granular (Figure 12.17). There is often loss of nuclear polarity and the nuclei show dispersed chromatin and one or two prominent eosinophilic nucleoli. Focal cytoplasmic CEA reactivity occurs and does not distinguish it from AIS.38

The Arias-Stella reaction involves the endocervical glands in 10% of gravid uteri (Figure 12.18). Superficial glands are more commonly involved than deep glands. The involved glands typically have a single layer of enlarged hyperchromatic pleomorphic nuclei that protrude into the lumen producing a ‘hobnail’ appearance. The glandular cells may also show intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions as well as optically clear nuclei. Mitoses are exceedingly rare or absent.39

Figure 12.18 Arias-Stella reaction. Hyperchromatic ‘hobnail’ nuclei protruding into the gland lumina.

In contrast to AIS, microglandular hyperplasia lacks significant nuclear atypia (Figure 12.19), lacks pseudostratification, has rare mitotic figures, and p16INK4A immunoreaction is negative. AIS, however, may occasionally involve areas of microglandular hyperplasia and, in such cases, the presence of residual microglandular hyperplasia uninvolved by AIS is the key to establishing the diagnosis. Similarly, AIS may also extend into other benign endocervical glandular lesions, such as tunnel clusters.

Figure 12.19 Microglandular hyperplasia. The small glands lack significant nuclear atypia, pseudostratification, and mitotic figures.

A stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion (SMILE) exhibits stratified epithelium resembling CIN in which there is conspicuous mucin production (Figure 12.20). Mucin is present throughout the epithelium, varying from indistinct cytoplasmic clearing to discrete vacuoles. The lesion shows a rounded or lobulated contour at the epithelial–stromal interface and a high Ki-67/MIB1 index. SMILE is an unusual cervical intraepithelial lesion best regarded as a variant of cervical columnar cell neoplasia based on phenotype. SMILE is frequently associated with CIN, AIS, or invasive carcinoma.40

Biologic Behavior and Treatment

AIS is treated either by conization or by hysterectomy. Because of the multicentric distribution of AIS, recurrence occurs more often after conization than after hysterectomy, particularly if the lesion involves the margins of the cone.41 Even though in young women who are desirous of preservation of fertility cone biopsy may be selected, currently the definitive therapy for AIS remains hysterectomy.42 In a meta-analysis, 27% of patients treated with conization where the margins were free of abnormality had residual AIS in the subsequent hysterectomy specimen.43 This figure reached 59% if the margins on cone biopsy were positive.44–48 Some authors believe that the disease-free endocervical margin in a cone biopsy must be at least 10 mm to consider the lesion completely excised.45 If a lesser procedure is performed, cold knife or laser cone biopsy is more effective than loop electrosurgical excision, especially for the endocervical margin.49,50 Furthermore, patients with AIS and positive margins on cone biopsy are at moderate risk of harboring an occult invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma that has already developed. The optimal management of the atypical glandular lesions that fall short of AIS is even more controversial, with treatment options including cytologic follow-up or management along the lines of AIS.

Adenocarcinoma

In developed countries, adenocarcinoma currently accounts for 15–20% of all carcinomas of the uterine cervix.51,52 Prior to 1970, it represented only 5% of cervical carcinomas. The relative frequency has increased due to a decrease in that of invasive squamous cell carcinoma, which is much more readily identified in its preinvasive stages by cytologic examination than adenocarcinoma. Nevertheless, there is evidence of an absolute increase in the incidence of adenocarcinoma in both the United States and Northern Europe, particularly in women under the age of 35 years.51–53

Almost 60% of cervical adenocarcinomas are associated with SIL or invasive squamous cell carcinoma.54,55 Also, several reports have suggested that HPV 16, 31, and, particularly, 18 may have a significant role in the causation of cervical adenocarcinomas. These HPV types have been identified in adenocarcinomas and adenosquamous carcinomas with a frequency of 80% or more.56–58 The HPV status, however, is not predictive of disease outcome. An association with prior use of oral contraceptive, particularly those with a strong progestogen component, has been described but it has not been totally proved. It is noteworthy that the introduction of oral contraceptive in the 1960s was followed a few years later by the recognition of microglandular hyperplasia, a proliferative cervical lesion that develops in women using oral contraceptive.59 Although the similar temporal association suggested the possibility of a causal relationship between oral contraceptive and cervical adenocarcinoma, the association was diminished when adjusted for HPV.17 On the other hand, use of hormone replacement therapy, especially unopposed estrogens, in older women may be associated with an increased risk of cervical adenocarcinoma.60 Yet other reports indicate that cervical adenocarcinomas share some epidemiologic associations with endometrial carcinoma, including a slight tendency toward patient obesity, hypertension, and nulligravidity.61

Patients with adenocarcinoma of the cervix, particularly those with minimal-deviation mucinous adenocarcinoma, tend to develop mucinous tumors of the ovary and some of them have the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.62

Adenocarcinoma of the cervix is almost always a tumor of adult life; it is rare in the first decade and uncommon in the second decade.51 The average age ranges from 47 to 53 years.52 The patients present with abnormal uterine bleeding in 80–90% of cases. Occasional patients complain of vaginal discharge or pain. The tumor is asymptomatic in up to 20% of cases and is usually discovered in such cases because of an abnormal Pap smear. The diagnostic ability of cytopathology for detecting cervical adenocarcinoma varies according to the expertise of the pathologist and the sampling techniques used. Most patients with adenocarcinoma of the cervix have cytologic abnormalities. At the time of diagnosis, 67.8% of tumors are FIGO stage I, 23.8% stage II, 7.4% stage III, and 1% stage IV. The older the age group, the higher the proportion of cases with a more advanced FIGO stage.63

Microinvasive (Early Invasive) Adenocarcinoma

Pathology

In contrast to microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma, the glandular counterpart has received little attention in the literature. The ideal definition of microinvasive adenocarcinoma should guarantee the safety of conservative therapy; it should describe an invasive adenocarcinoma small enough not to be associated with metastasis. The main diagnostic problems are, first, to distinguish microinvasive adenocarcinoma from AIS and, second, how to measure the depth of invasion.64

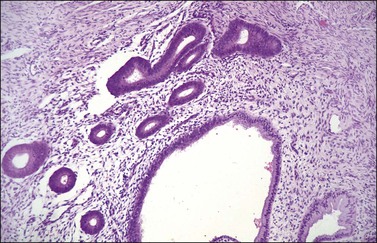

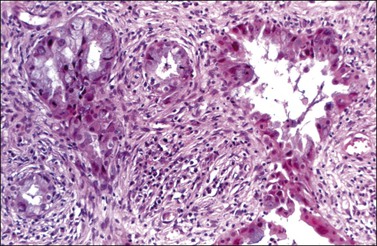

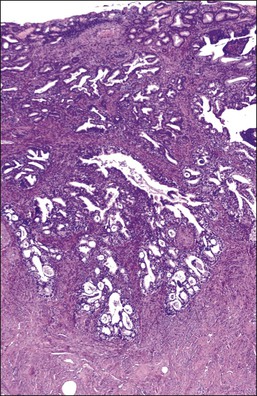

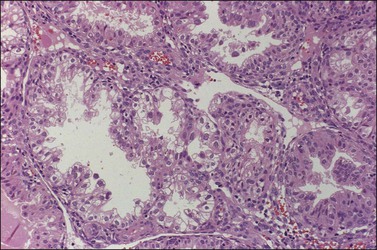

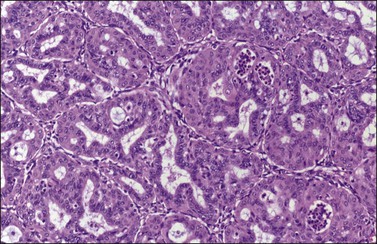

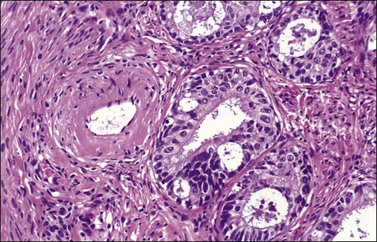

The criteria for microinvasion include: (1) obvious stromal invasion by epithelial finger-like processes arising from glands involved by AIS or detached cellular clusters with abundant pink cytoplasm lying free in the stroma; (2) obliteration of the normal endocervical crypts; (3) complex intraglandular cribriform or papillary growth patterns; (4) stromal edema, inflammation, and desmoplasia; and (5) extension below the deep margin of normal endocervical glands64 (Figures 12.21 and 12.22). If the distance between neoplastic glands and thick-walled blood vessels is less than the thickness of the vessel wall, invasion should be suspected65 (Figure 12.23). Not all of these features are present in every case and invasion is indicated by the gland pattern and haphazard distribution on low-power examination. The depth of invasion is usually measured from the surface epithelium (tumor thickness) rather than from the point of origin. This is due to the difficulty to determine where AIS ends and stromal invasion begins64 (Figure 12.24). Indeed, the identification of early invasion in cervical glandular lesions may not always be possible, and in approximately 10–15% of patients the pathologist may be uncertain.

Figure 12.21 Microinvasive adenocarcinoma. The irregular growth pattern and irregular outlines of the glands are indicative of early invasive carcinoma.

Figure 12.23 Microinvasive adenocarcinoma. A tumor gland appears adjacent to a thick-walled blood vessel.

Figure 12.24 Microinvasive adenocarcinoma. In some cases it may be difficult to distinguish AIS from invasive adenocarcinoma. The deeply invasive glands suggest this tumor is invasive.

Cytologic Correlation

Microinvasive adenocarcinoma can sometimes be predicted cytologically. Features include those of AIS, which are always present. Syncytia of glandular cells, small cells in supercrowded sheets, papillary groupings, and dissociated cells are suggestive of the diagnosis. Nuclear features include pleomorphism with irregular chromatin and nucleoli. Tumor diathesis may also be present. Collectively, these criteria help predict microinvasion in over two-fifths of cases.66,67 In practical terms, microinvasion can be accurately defined only histologically. The major role of cytology in this circumstance is identifying the existence of high-grade neoplasia of endocervical columnar cell origin.

Biologic Behavior and Treatment

It appears that microinvasive adenocarcinoma behaves in the same way as its squamous counterpart. What is uncertain is the maximum size at which less than radical treatment is safe. When microinvasive adenocarcinoma does not invade beyond 5 mm, the margins are free, and the conization specimen has been totally embedded, conservative treatment is acceptable.64 A review of the literature revealed that only five (2%) of 219 patients with microinvasive adenocarcinoma invading less than 5 mm were found to have metastasis after pelvic lymph node dissection.64 Of these patients, 3.4% developed recurrences and 1.4% died. No patient treated by radical hysterectomy had parametrial involvement.63 The relationship of capillary–lymphatic space involvement, lymph node metastasis, and recurrence remains uncertain. Conization is considered acceptable treatment only if the specimen has been adequately sampled and the margins free. Fifty percent of patients with positive margins had residual disease in the subsequent hysterectomy specimen.64

In a SEER database review of 301 cases of microinvasive adenocarcinoma of which 131 were FIGO stage IA1 and 170 were stage IA2, only one of 140 women who had lymphadenectomy had a single positive lymph node. This patient had stage IA2 disease. Moreover, of four women with tumor-related deaths, three were stage IA2. Overall, the prognosis for microinvasive adenocarcinoma is excellent and, in 96 cases, simple hysterectomy alone proved adequate.68 In a more recent study evaluating depth of invasion, none of 48 patients with tumor under 5 mm invasion had involved parametria or nodes; whereas eight of the 36 with invasion greater than 5 mm had nodal metastases. None of the former developed a recurrence whereas one-sixth of the latter had recurrent disease.69 These data argue that, for patients with tumor less than 5 mm invasion and negative margins, pelvic lymphadenectomy may be omitted.69 Similarly, in a study of 32 patients with FIGO stage IA1 and IA2 adenocarcinomas of the cervix where invasion was strictly defined, the method of measurement was standardized and villoglandular, serous, and clear cell carcinomas were excluded, no recurrences have been reported to date.70 Clearly, some young women with early invasive adenocarcinomas might best be served by treating the tumor in the same way as microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Invasive Adenocarcinoma

Although less common than squamous cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas generally cause greater diagnostic difficulty because of their relative rarity, their varied patterns, and the potential for confusing them with several non-neoplastic lesions. Some variants are associated with a distinctive biologic behavior. A classification of these tumors is presented in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1

Modified WHO Histologic Classification of Adenocarcinomas of the Uterine Cervix

| AIS | 8140/2 |

| Early invasive adenocarcinoma | 8140/3 |

| Adenocarcinoma, usual-type | 8140/3 |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 8480/3 |

| Intestinal-type | 8482/3 |

| Signet-ring cell type | 8144/3 |

| Gastric-type (minimal deviation adenocarcinoma) | 8490/3 |

| NOS | 8480/3 |

| Villoglandular | 8262/3 |

| Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 8380/3 |

| Clear cell adenocarcinoma | 8310/3 |

| Serous adenocarcinoma | 8441/3 |

| Mesonephric adenocarcinoma | 9110/3 |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 8560/3 |

| Glassy cell variant | 8015/3 |

The 2014 WHO classification divides these tumors into usual-type adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinomas (including intestinal-type, signet-ring cell type, gastric-type or minimal deviation adenocarcinoma, and NOS), villoglandular adenocarcinoma, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, serous adenocarcinoma, and mesonephric adenocarcinoma.4 A number of uncommon variants will also be covered in this chapter.

Adenocarcinoma, Usual-Type

Pathology

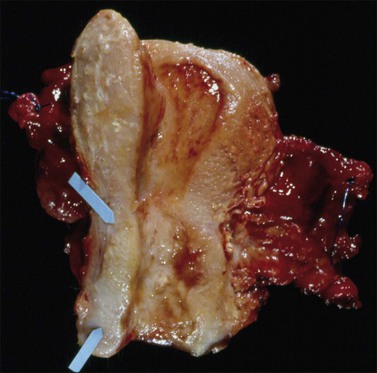

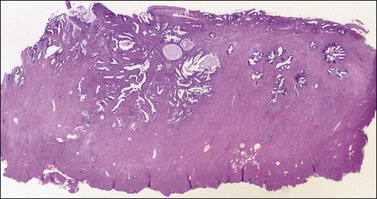

Grossly, half of cervical adenocarcinomas are exophytic, usually as a polypoid or papillary mass. Some may be nodular, with diffuse enlargement (Figure 12.25) or ulceration, and some tumors present as a barrel-shaped cervix. About one-sixth are small and not visible, usually because of their location within the endocervical canal. Even in the absence of visible signs or symptoms, the tumor may infiltrate deeply into the wall (Figure 12.26). Generally, the gross appearance is not helpful in predicting the histologic appearance.

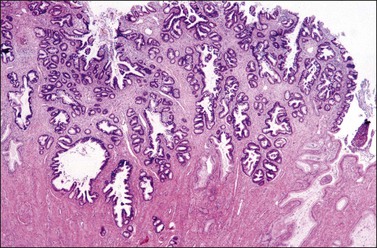

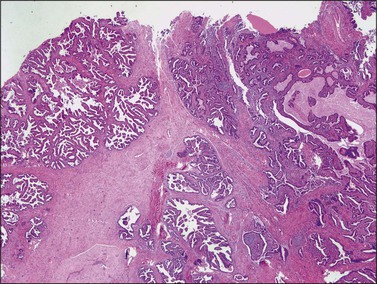

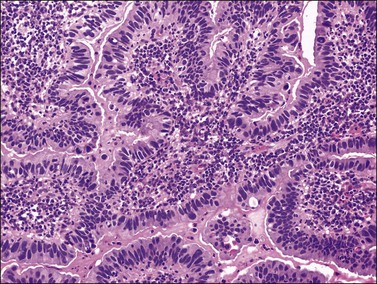

As indicated earlier, most tumors are moderately differentiated and show little intracytoplasmic mucin; thus, the tumor glands resemble those of endometrioid carcinoma or exhibit a mixed endocervical and endometrioid appearance. This has led to confusion, with these tumors regarded as endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Gland size may vary from small to cystic, and the glands may be widely spaced or closely packed, often with a cribriform pattern. Papillae may be present, but are rarely conspicuous (Figure 12.27). Mitoses are readily found and apoptotic bodies are commonly seen (Figure 12.28). The tumors are usually associated with a desmoplastic or a prominent fibromatous stroma. Some tumors show prominent numbers of acute inflammatory cells within both the stroma and the gland lumens.

Figure 12.27 Adenocarcinoma, usual-type. The glands are arranged in a complex pattern. Stroma is abundant.

Figure 12.28 Adenocarcinoma, usual-type. The papillae are lined by stratified epithelial cells showing numerous mitoses and apoptotic bodies. The stroma contains abundant chronic inflammatory cells.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree