Patient Story

A 65-year-old hypertensive black man presented to the emergency department with onset of right face, arm, and hand paralysis, and difficulty communicating. Rapid diagnostic testing using MRI revealed an ischemic infarct in the left middle cerebral artery (Figure 230-1). He was evaluated by a stroke response team and was found to be a candidate for tissue plasminogen activator (TPA). After the stroke, he was treated with aspirin, antihypertensives, and cholesterol-lowering medication. He recovered 80% of his neurologic deficit over the next 3 months. Figure 230-2 is a noncontrast CT image of this patient 2 weeks later.

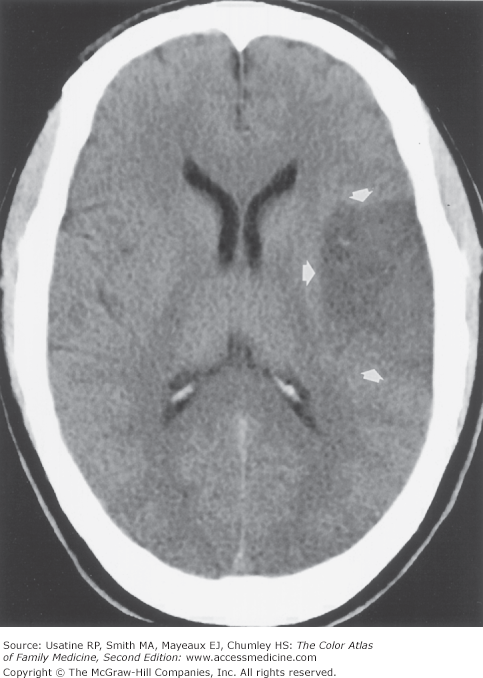

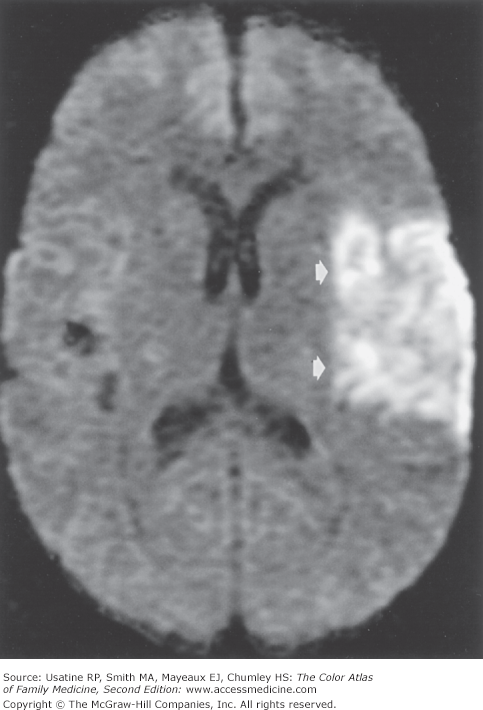

Figure 230-1

Acute left middle cerebral artery infarct on MRI of a 65-year-old hypertensive man. The MRI demonstrates increased signal intensity (arrows). Abnormalities in MRI occur before those seen on CT during ischemic strokes. (Courtesy of Chen MYM, Pope TL, Ott DJ. Basic Radiology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004:338.)

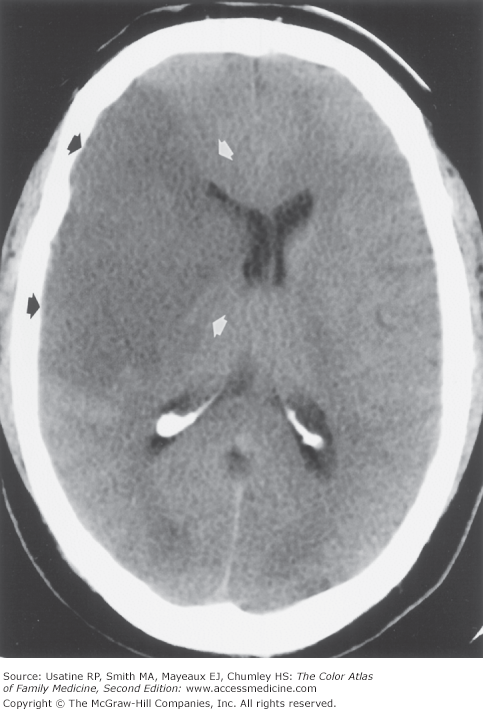

Figure 230-2

Noncontrast CT image of a subacute left middle cerebral artery infarct (arrows). This was done 2 weeks after the stroke in the same patient as previous figure. CT findings occur later than MRI findings in ischemic strokes. (Courtesy of Chen MYM, Pope TL, Ott DJ. Basic Radiology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004:338.)

Introduction

Epidemiology

- Cerebral vascular accidents (CVAs) affect approximately 700,000 people per year in the United States, most being older than age 65 years.1

- Ischemic (66%) and hemorrhagic (10%) strokes account for most strokes.1

- Prevalence of stroke and mortality are higher in blacks than in whites. Prevalence is 753 versus 424 per 100,000 and mortality is 95.8 versus 73.7 per 100,000 for black and white men, respectively.1

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- CVAs are typically classified into cardioembolic (15% to 22%), large vessel (10% to 12%), small vessel (15% to 18%), other known cause (2% to 4%), and undetermined cause (46% to 51%).2

- Ischemic CVAs occur when atherosclerosis progresses to a plaque, which ruptures acutely. Each step of this process is mediated by inflammation.3

- Hemorrhagic CVAs occur when vessels bleed into the brain, usually as the result of elevated blood pressure.

- Other known causes of CVAs include inflammatory disorders (giant cell arteritis, systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatous angiitis, syphilis, and AIDS), fibromuscular dysplasia, drugs (cocaine, amphetamines, and heroin), hematologic disorders (thrombocytopenia, polycythemia, and sickle cell), and hypercoagulable states.

Risk Factors

- Hypertension (HTN)—The predominant risk factor for more than 50% of all strokes. Prehypertension (blood pressure in the range of 130 to 139/85 to 89) carries a hazard ratio of 2.5 for women and 1.6 for men.4

- Cigarette smoking carries a hazard ratio of 1.62 for ischemic stroke and 2.56 for hemorrhagic stroke.5

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) increases the risk of having a stroke six-fold.4

- Black patients at ages 45 and 65 are 2.9 and 1.66 times more likely to have a stroke compared to white patients.6

- Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of stroke. The CHADS2 (congestive heart failure [CHF], HTN, age >75, DM, stroke) scoring system (see below) separates patients into low risk (stroke rate 1% to 1.5% per year), moderate risk (2.5%), high risk (4%), and very high risk (7%).4

- Body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 carries a hazard ratio of 1.45 for ischemic stroke but does not increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke.5

Diagnosis

- History of risk factors, including older age, HTN, cigarette smoking, type 2 DM, or previous transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke.

- Acute onset of neurologic signs and symptoms based on the site of the CVA (see “Typical Distribution” below).

TIA or stroke can occur in any area of the brain; common areas with typical symptoms include the following:

- Middle cerebral artery is the most common ischemic site (Figure 230-3):

- Superior branch occlusion causes contralateral hemiparesis and sensory deficit in face, hand, and arm, and an expressive aphasia if the lesion is in the dominant hemisphere.

- Inferior branch occlusion causes a homonymous hemianopia, impairment of contralateral graphesthesia and stereognosis, anosognosia and neglect of the contralateral side, and a receptive aphasia if the lesion is in the dominant hemisphere.

- Superior branch occlusion causes contralateral hemiparesis and sensory deficit in face, hand, and arm, and an expressive aphasia if the lesion is in the dominant hemisphere.

- Internal carotid artery (approximately 20% of ischemic strokes) occlusion causes contralateral hemiplegia, hemisensory deficit, and homonymous hemianopia; aphasia is also present with dominant hemisphere involvement.

- Posterior cerebral artery occlusion causes a homonymous hemianopia affecting the contralateral visual field.

These tests may be helpful in the context of an acute stroke, particularly when the cause of the stroke is not immediately evident:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree