Overview

Pathology, in the broadest terms, is the study of disease. Disease occurs for many reasons. Some diseases represent spontaneous alterations in the ability of a cell to proliferate and function normally, and in other cases, disease results when external stimuli produce changes in the cell’s environment that make it impossible for the cell to maintain homeostasis. In such situations, cells must adapt to the new environment. These adaptations include hyperplasia, hypertrophy, atrophy, and metaplasia, and can be physiologic or pathologic, depending upon whether the stimulus is normal or abnormal. A cell can adapt to a certain point, but if the stimulus continues beyond that point, failure of the cell, and hence the organ, can result. If cells cannot adapt to the pathologic stimulus, they can die. This chapter will discuss cellular adaptation, cell injury, cellular accumulations, and cellular aging.

Cellular Adaptation

Overview: The four basic types of cellular adaptation to be discussed in this section are hyperplasia, hypertrophy, atrophy, and metaplasia.

Basic description: Increase in the number of cells.

Types of hyperplasia

- Physiologic hyperplasia: Occurs due to a normal stressor. For example, increase in the size of the breasts during pregnancy, increase in thickness of endometrium during menstrual cycle, and liver growth after partial resection.

- Pathologic hyperplasia: Occurs due to an abnormal stressor. For example, growth of adrenal glands due to production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) by a pituitary adenoma, and proliferation of endometrium due to prolonged estrogen stimulus.

Important point regarding hyperplasia: Only cells that can divide will undergo hyperplasia; therefore, hyperplasia of the myocytes in the heart and neurons in the brain does not occur.

Basic description: Increase in the size of the cell.

Types of hypertrophy

- Physiologic hypertrophy: Occurs due to a normal stressor. For example, enlargement of skeletal muscle with exercise.

- Pathologic hypertrophy: Occurs due to an abnormal stressor. For example, increase in the size of the heart due to aortic stenosis. Aortic stenosis is due to a change in the aortic valve, which obstructs the orifice, resulting in the left ventricle working harder to pump blood into the aorta.

Morphology of hyperplasia and hypertrophy: Both hyperplasia and hypertrophy result in an increase in organ size; therefore, both cannot always be distinguished grossly, and microscopic examination is required to distinguish the two (Figure 1-1).

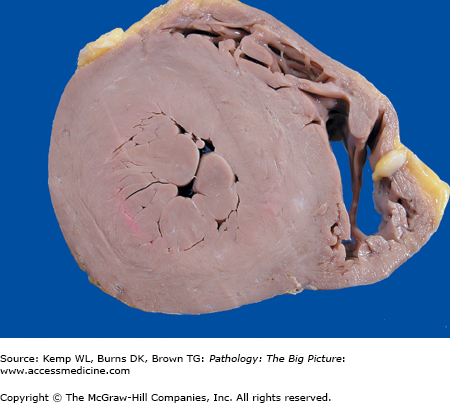

Figure 1-1.

Cross-section of the heart of a patient with systemic hypertension. The patient had high blood pressure, which increased the workload of the left ventricle and resulted in concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricular myocardium. In response to the increasing pressure load, the cardiac myocytes increased their content of contractile proteins, resulting in enlargement of individual myocytes.

mechanisms by which hyperplasia and hypertrophy can occur: Up regulation or down regulation of receptors and induction of new protein synthesis. The two processes can occur together. For example, up regulation of receptors results in the induction of new protein synthesis; or up and down regulation of receptors and induction of new protein synthesis can occur as independent processes. The types of new proteins induced include transcription factors (e.g., c-Jun, c-Fos), contractile proteins (e.g., myosin light chain), and embryonic proteins (e.g., β-myosin heavy chain).

Basic description: Decrease in the size of a cell that has at one time been of normal size.

Types of atrophy

- Physiologic atrophy: Occurs due to a normal stressor. For example, decrease in the size of the uterus after pregnancy.

- Pathologic atrophy: Occurs due to an abnormal stressor. In general, atrophy is due to the loss of stimulus to the organ. Specific types of loss of stimulus include loss of blood supply or innervation, loss of endocrine stimulus, disuse, mechanical compression, decreased workload, or aging.

Gross morphology of atrophy (Figure 1-2): The organ is smaller than usual. Atrophy occurs in a once normally developed organ. If the organ was never a normal size (i.e., because it did not develop normally), the condition is called hypoplasia.

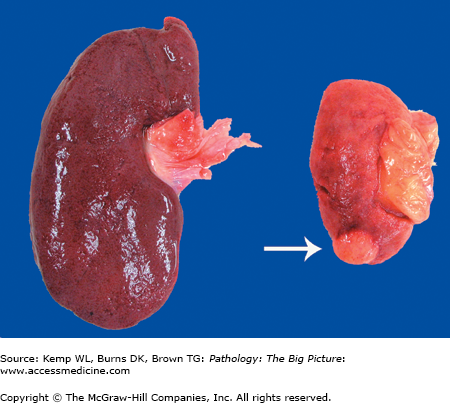

Figure 1-2.

Kidneys from two different patients. The kidney on the left is normal in size, whereas the kidney on the right is atrophic. The kidney on the right was from a patient who had severe atherosclerosis of the renal artery, which led to ischemia (i.e., decreased perfusion) of the organ. Due to an insufficient supply of oxygen and nutrients, the cells of the kidney decreased in size to adapt. An incidental renal cell carcinoma is visible near the pole of the atrophic kidney (arrow).

Basic description: Change of epithelium at a site, or location, from one type of epithelium to another type. In metaplasia, the epithelium is normal in appearance but in an abnormal location.

Mechanism of metaplasia: The epithelium normally present at a site cannot handle the new environment so it converts to a type of epithelium that can adapt.

Examples: Barrett esophagus is due to reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, which causes the epithelium type to convert from squamous to glandular (Figure 1-3 A and B). Squamous metaplasia in the lungs is due to exposure of respiratory epithelium to toxins in cigarette smoke.

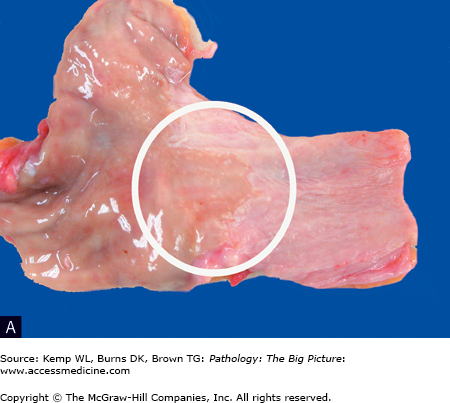

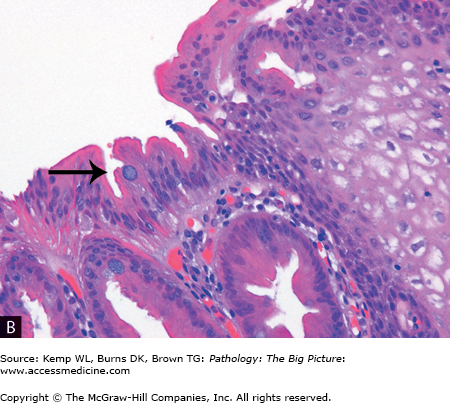

Figure 1-3.

Barrett esophagus (glandular metaplasia). A, This specimen is taken from the region of the gastroesophageal junction and includes a segment of proximal stomach (on the left side) in continuity with the distal esophagus (on the right side). A small patch of mucosa with an appearance similar to the gastric mucosa extends proximally (circle), above the gastroesophageal junction. In this area, the normal stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus has been replaced by glandular epithelium. Glandular metaplasia of the esophagus occurs in response to gastric acid reflux. B, The right side of the image shows stratified squamous epithelium, and the left side shows glandular epithelium, with goblet cells present (arrow). Transformation of one type of tissue to another type of tissue is termed metaplasia; in this case, stratified squamous epithelium was transformed to intestinal-type epithelium. Hematoxylin and eosin, 200×.

Cell Injury

Causes of cell injury: Hypoxia (decreased oxygen), ischemia (decreased blood flow), physical and chemical agents, trauma, infectious agents, radiation and toxins, metabolic abnormalities (genetic or acquired), immune dysfunction (hypersensitivity reactions and autoimmune disease), aging, and nutritional imbalances.

- Hypoxia and ischemia are two common sources of cellular injury. Of the two, ischemia is much more damaging because it involves hypoxia plus a lack of other nutrients and an accumulation of toxic cellular metabolites.

- When does injury occur? This varies from cell to cell. It depends upon the type, duration, and severity of injury, and the type, adaptability, and makeup of the affected cell.

- Cellular injury may or may not result in the death of the cell. Four cellular systems are especially vulnerable to cellular injury, and include:

DNA

Cell membranes

Protein generation

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production

- Although some of the causes of cellular injury have specific mechanisms, the mechanism of cellular injury due to many substances is not understood.

Hypoxia: In general, decreased oxygen results in decreased production of ATP. ATP is normally required by the Na/K+ pump and Ca2+ pump. When ATP levels decrease, these pumps fail and sodium (along with water, which follows sodium) enters the cell, causing swelling. Also, calcium enters the cell, which activates endonucleases, proteases, phospholipases, and DNAses, which damage the cell. Cells switch to anaerobic respiration to produce ATP, which results in accumulation of lactic acid. The accumulation of lactic acid decreases the cellular pH. Decreased pH causes disaggregation of ribosomes from endoplasmic reticulum.

Generation of oxygen-derived free radicals by a stressing agent

Basic description of free radical: A free radical is a molecule with an unpaired electron in the outer orbit. Another term for oxygen-derived free radicals is reactive oxygen species.

How free radicals are generated: Free radicals are generated by normal physiologic reduction-oxidation reactions, ultraviolet light, x-rays and ionizing radiation, and transitive metals. Also, metabolism of exogenous chemicals, such as carbon tetrachloride, induces formation of reactive oxygen species.

Damage by free radicals: Lipid peroxidation (damages cell membranes), DNA fragmentation, and protein cross-linking (e.g., sulfhydryl groups), which results in increased degradation and decreased activity.

Methods to prevent formation of reactive oxygen species

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree