- Not all patients with cancer will require specialist palliative care.

- Care can be shared between an oncologist and a palliative medicine physician.

- Patients may need intermittent palliative medicine input from diagnosis.

- Much can be done by those trained in the principles of general palliative care.

Introduction

The growth of palliative medicine and palliative care services (PCS) has been rapid in the last 10 years. The expansion of these services has led to increased specialization of palliative care. Not all patients with cancer will require specialist palliative care as their symptoms and problems can be dealt with by staff, such as oncology ward nurses, who are able to give general supportive care. Hospices and palliative care units are increasingly used as tertiary centers prioritizing those patients with complex physical or psychological problems. Oncology patients may need interventions from palliative medicine at any time during their illness, and in the United Kingdom they may be under the care of both the oncologist and palliative medicine physician simultaneously.

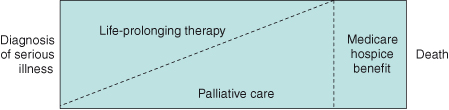

In the United States, there is an artificial boundary driven by the reimbursement system of Medicare and Medicare hospice benefit. This results in patients being transferred to the hospice system only when life-prolonging treatments are ineffective and death is imminent. This is beginning to change with the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice guidelines from the United States stating that “the effort to integrate palliative care into all health care for persons with debilitating and life-threatening illnesses should help to ensure that pain and symptom control, psychological distress, spiritual issues and practical needs are addressed with patient and family throughout the continuum of care.”

Key Concepts

The model shown in Fig. 19.1 illustrates the continuum of palliative care, which should be accessed in acute hospitals, hospices, or the community, and differentiates between palliative care and what is called “terminal care” in the United Kingdom and “hospice care” in the United States.

Communication with the Cancer Patient

Excellent care is difficult to achieve without good communication. By finding out what your patients are thinking, and tailoring information to what they want to know, communication can be markedly improved. Current training emphasizes key tasks in communication:

- Elicit the patient’s main problems, the patient’s perceptions of these, and the physical, emotional, and social impact of these problems on the patient and family;

- tailor information to what the patient wants to know, checking his or her understanding;

- determine how much the patient wants to participate in decision making (when treatment options are available);

- discuss treatment options so that the patient understands the implications;

- maximize the chance that the patient will follow agreed decisions about treatment and advice about changes in lifestyle.

In order to be able to do all these. Tasks, oncologists need to be able to communicate clearly and effectively.

It is now widely acknowledged that many doctors struggle with effective communication. They feel pressure of time and worry that if they explore distress during a consultation, they will be faced with a situation that they cannot handle. Consequently, many doctors use “blocking strategies” to prevent further disclosure.

Blocking Strategies

- Offering “premature advice or reassurance”

Patient: “I am so worried… ” (unsaid: “about my wife”)

Doctor: (assuming she knows what the patient is worried about) “The chemotherapy will work well and you’ll be feeling better before you know it.”

- Explaining distress as normal

Patient: “I’m so frightened.”

Doctor: “Everybody I see feels frightened at first but that soon goes.”

- Attending to physical aspects only

Patient: “I’m very worried.. .”

Doctor: “I see. How are your bowels?”

- Jollying patients along

Patient: “Oh I am upset about my cancer.”

Doctor: “But we should be able to cure it.”

- Switching topic

Patient: “My wife is so upset at the moment.”

Doctor: “Now have you got your blood test forms for the next cycle of chemo?”

Doctors use strategies like these in the mistaken belief that they help, both the patient, by preventing them from getting upset, and themselves by minimizing the distress that they are exposed to. In fact the opposite is true: they prevent patients from disclosing their anxieties and problems and lead to increased distress for the patient and the doctor. Exploring these concerns can lead to better joint management of problems. It can also aid compliance with drugs and treatment programs.

When Is Palliative Care Appropriate for Cancer Patients?

Many oncologists will look after patients until their death. The increasing use of palliative chemotherapy has prolonged the palliative phase in many patients. However, this has also raised new problems, including when to stop palliative chemotherapy and how to ensure the patient’s agreement with the decision.

Palliative care may be required at any time during the patient’s treatment. Referral to the palliative care team (PCT) should also be considered as chemotherapy treatment is discontinued.

Palliative Care Assessment

The assessment of patients needs to be specific, be detailed, and encompass psychological, social, and existential issues as well as physical problems. Only by paying close attention to detail will the physician be able to identify the cause of problems and treat them effectively. For instance, a patient’s pain may seem unresponsive to opioids not because the morphine is ineffective but because the patient is fearful of addiction and has not been taking the tablets.

Symptom Control

A retrospective case study of 400 patients referred to PCTs showed that 64% had pain, 34% anorexia, 32% constipation, 32% weakness, and 31% dyspnea. The most common symptoms are covered in this chapter. For other problems, the reader may consult the reference list at the end of the chapter.

Pain

This may result from the tumor itself, indirectly from tissues related to the cancer, or from other unrelated causes. In a retrospective study in 1995, 2074 carers were asked about the patient’s experiences in the last year of life. They reported that 88% of patients were in pain at some time, 47% of patients’ pain was either only partially controlled or not controlled at all by general practioners (GPs), and 35% had pain partially or not at all controlled by hospital doctors.

A study of 200 cancer patients referred to a pain clinic showed that 158 had pain caused by tumor growth; visceral involvement was the cause in 74 cases, bone secondaries in 68 cases, soft tissue invasion in 56 cases, and nerve compression or infiltration in 39 cases. Many patients had more than one type of pain.

Principles of Pain Control

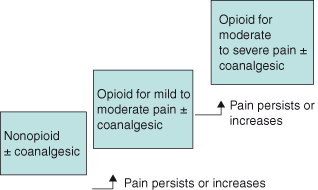

The analgesic ladder (Fig. 19.2) is a simple scheme which emphasizes the stepwise approach to pain due to cancer and the need to take regular analgesics.

Move up the ladder if the current step is ineffective. All the medication has to be given regularly and orally unless unable to do so.

Some patients will go directly from Step 1 to Step 3. Regular nonsteroidals or regular paracetamol can be used as opiate-sparing drugs.

Opioids

There are a variety of long-and short-acting opioids available that can be used for patients requiring step 3 analgesics; however, not all opioids are available in all countries (Table 19.1). Morphine remains the most frequently used opioid. Others can be used either for a different route of administration or in case of side effects.

Table 19.1 Commonly used opioids

| Morphine | 4-, 12, and 24-hour preparations (can be used parenterally) |

| Oxycodone | 4- or 12-hour preparation (parenteral preparation available) |

| Hydromorphone | 4- or 12-hour preparation |

| Methadone | Useful for patients with neuropathic pain and partially opiate-sensitive pain |

| Fentanyl | Transdermal patch. Change every 3 days. Reservoir of drugs for 12–24 hours after patch removed. Only use in stable pain. Oral transmucosal preparations are also available for buccal use. Intravenous analogs are becoming available. |

| Buprenorphine | Low-dose transdermal patch and sublingual preparation |

| Diamorphine | High solubility; can be given subcutaneously either as a stat dose or via a syringe driver (not available worldwide) |

| Levorphanol | Orally or parenterally |

| Oxymorphone | Suppository or parenteral preparation |

Common side effects of opioids are drowsiness, nausea, constipation, xerostomia, vivid dreams, and itching. Opiate toxicity is characterized by pinpoint pupils, visual hallucinations, twitching, agitation and confusion, and respiratory depression. If patients are experiencing side effects from one formulation, it is worth trying another drug.

Patients’ needs for opioids will vary markedly. It is therefore logical to ascertain a patient’s needs before commencing long-acting preparations. The usual method is to start a patient on a regular 4-hourly dose of short-acting opioid judging the dose on age, renal function, and previous drug requirement. They are also allowed “breakthrough doses” for pain. After 48 hours, it should be possible to calculate their 24-hour opiate requirement and convert to a long-acting preparation. Whatever be the long-acting preparation, there should be a short-acting opiate given for breakthrough pain.

Cancer Pain Syndromes

Bone Pain

This is a very common cause of cancer pain. Many patients will achieve good pain control with radiotherapy and bisphosphonates. NSAIDs may be effective or analgesics as per the analgesic ladder may be required.

Incident Pain

This is most commonly seen in patients with spinal bone metastases and may be one of the most difficult pain syndromes to treat effectively. The patient will generally be pain- free at rest but experience severe and sometimes incapacitating pain when bearing weight. If the pain is treated with sufficient analgesia to cover the periods of activity, the patient will be sedated and overdosed at rest, and if the dose is only sufficient for rest pain, the patient will stay immobile.

Management includes optimum treatment for the cause, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and bisphosphonates. Opiates should be used as previously described; the use of short-acting oral fentanyl preparations may be helpful, with the addition of coanalgesics for bone pain and neuropathic pain. It may be necessary to change to methadone or add corticosteroids. Epidural or intrathecal analgesia may be required. Physiotherapists and occupational therapists may be useful in moderating either activity or the environment in order to reduce episodes of pain.

Liver Capsule Pain

This is due to the distention of the capsule and may be associated with diaphragmatic irritation. The pain may respond to NSAIDs or steroids; otherwise opiates may be required.

Bowel Pain

Intra-abdominal cancer may present with poorly localized pain due to peritoneal inflammation, vascular or lymphatic blockage, or bowel spasm secondary severe to serosal or intraluminal disease. Constipation may be an additional problem due to drugs, bowel dysfunction, or a combination of both.

Nerve Compression or Plexopathy

Patients with pelvic tumors, pancreatic cancer, spinal secondaries, apical lung tumors, and head and neck tumors may have severe neuropathic pain (Table 19.2). Patients will typically describe their pain as “burning” or “stabbing” and may have associated loss of sensation or reflexes. The pain may be opiate-sensitive in approximately one third of patients; others will need the addition of drugs specifically for neuropathic pain such as gabapentin.

Table 19.2 Descriptors in neuropathic pain

| Allodynia | Increased sensitivity such that stimuli that are normally innocuous produce pain |

| Hyperalgesia | Increased sensitivity to a painful stimulus |

| Hyperpathia | Prolonged response to a stimulus even after its removal |

Patients with difficult pain should be referred to the palliative care or pain team.

Coanalgesics

These are drugs that are used, often in combination with opioids, for a variety of pains, often neuropathic in origin. They include antidepressants and antiepileptic agents such as gabapentin, though the mechanism of benefit is not fully understood (Table 19.3).

Table 19.3 Commonly used coanalgesics

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Bone pain or other pain, particularly if inflammatory component potentiates opiates |

| Tricyclic antidepressant (e.g. amitriptyline) | Neuropathic pain. Initial drowsiness may subside as analgesic effect becomes effective after 5 days. |

| Antiepileptics (e.g. gabapentin, pregabalin, and carbamazepine) | Neuropathic pain. Newer drugs have less interactions and side effects. |

| Steroids | Useful for short periods for pain due to nerve compression |

| Ketamine | Effective for neuropathic pain. Suppress hallucinations with haloperidol or diazepam. |

| Benzodiazepines | For muscle spasm and myofascial pain |

| Paracetamol/acetaminophen | Used as a coanalgesic to potentiate the effects of opiates |

It may be necessary to give patients a combination of these drugs.

Anesthetic Techniques in Pain Control

These techniques are used to either block the pain pathway or deliver analgesia through another route (e.g. spinally).

Nerve Blocks

They are usually carried out in patients who have pain localized to a nerve distribution and do not respond to analgesia. They are usually carried out with local anesthetic in the first instance to assess response before the nerve is ablated with phenol, cryotherapy, or radio frequency.

Epidural and Intrathecal Catheters

They may be used to place opiates, local anesthetic, and steroids spinally for patients with back or pelvic pain.

Respiratory Symptoms

Breathlessness is a common symptom and occurs in many cancers. It is thought that toward the end of life respiratory muscle weakness plays a large part, but earlier on in the illness there are many treatable causes. Thus, breathlessness may result from the cancer itself (pleural effusion, lung metastases, or massive ascites), but also from preexisting conditions or anticancer treatment (anemia).

There is evidence in lung cancer that nondrug treatments can be of help. Examples of such treatments include teaching breathing exercises and energy conservation techniques and explaining the cause of the breathlessness. Additional drug treatments, including β2 agonists, should be used if required.

A recent systematic review has shown benefit of opiates orally or subcutaneously for the treatment of cancer-related breathlessness. Benzodiazepines may improve panic associated with breathlessness. Some patients who are hypoxic may benefit from supplemental oxygen.

Terminal Breathlessness

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree