Care of Stomas

Laurie Maidl

Jill Ohland

This chapter provides an overview on the management of ostomies. An intestinal stoma can be a life-altering event for many individuals. The location of the stoma on the abdomen, stoma construction, and appropriate appliance management are all key factors in the adjustment of the person with an ostomy.

Role of the Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurse

Ostomy surgery significantly alters bowel function, necessitating physiologic and psychosocial adaptation. A wound, ostomy, and continence (WOC) nurse is a specialist who assists the patient and family with ostomy care during their adjustment to life with an ostomy. In the preoperative setting, the WOC nurse discusses the surgical procedure and lifestyle issues with the patient and his or her family, demonstrates various types of ostomy appliances, and marks the stoma site on the patient’s abdomen.

Postoperatively, in the hospital, the WOC nurse assists the patient to learn management of the stoma using an appropriate ostomy appliance. Dietary advice, peristomal skin care, and resuming activities of daily living are discussed. Rehabilitation, focusing on body image, sexuality, and return to normal life activities such as work or school is also discussed.

After hospital discharge, it is important for the patient to have regular contact with a WOC nurse to assist in management changes that may occur. These changes may include a decrease in stoma size, changes in body contour, stabilization of weight after surgery, and increasing activity with return to normal lifestyle. The adjustment to a fecal diversion occurs over time. In the years following ostomy surgery, the WOC nurse is available to assist with problem solving of peristomal skin complications, ostomy appliance management difficulties, and psychosocial concerns. In addition, this allows the patient to remain current with ostomy appliances that are available.

Stoma Construction

A stoma may be constructed as an end, loop, or double-barrel stoma. An end stoma is created by dividing the bowel completely. The proximal end of the bowel is brought up to the abdominal wall at the premarked stoma site, everted, and sutured to the skin. The distal portion of the bowel may be removed or may be closed and left in the abdomen. If the bowel is left in the abdomen, the option of reanastomosis could be addressed at a future date. If any portion of the bowel is left distal to the stoma, the patient will occasionally expel a mucous drainage from the anus. The mucous drainage is normal and will continue for as long as the patient is diverted.

A loop stoma is created by bringing a loop of bowel, either small or large intestine, to the skin level. The bowel is partially divided and both openings are sutured to the abdominal wall. The proximal bowel may be everted and the distal bowel sutured below the proximal stoma. The distal bowel opening would represent a mucous fistula. Mucous discharge would come from the distal stoma opening as well as from the anus during the time the bowel is diverted. Management of the stoma may be more difficult with the flush distal loop as mucus is secreted and can undermine the appliance edge, resulting in skin irritation and appliance leakage. The appliance opening would need to be fit to allow both stomas to empty into the pouch.

A double-barrel stoma is similar to a loop stoma, except that the bowel is completely divided and both ends of the bowel are brought to the abdominal wall and matured. The proximal stoma is the functioning stoma and the distal stoma secretes mucus. The stomas may be placed close together and pouched in one appliance opening, or they may be placed at different sites on the abdomen. If they are placed at different sites, there should be at least 4 in. distance between the two stomas to allow for an adequate pouching surface. The proximal stoma would always be managed with an appliance. The distal stoma may be managed with a pouch initially, and if the amount of mucus decreases significantly, it may be possible to manage this stoma with a gauze dressing. It is important for the patient to know that there will always be some type of discharge from the distal stoma, even though the bowel is diverted.

When a stoma is constructed, it is important that it protrudes at least 2 cm above the skin level. This would be true even with a descending or sigmoid colostomy. The stoma is edematous for 6 to 8 weeks after surgery and decreases in diameter as well as length during this time. As the stoma decreases in size, one that is adequately budded at the time of surgery should still have adequate protrusion when the edema resolves. Ideally the lumen of the stoma would be central, which would allow the effluent to empty into the pouch. If a stoma is flush with the skin or if the lumen empties near the skin level, the effluent can undermine the appliance seal, causing appliance leakage and skin irritation.

Types of Stomas

Stomas typically managed with a pouching system are jejunostomy, ileostomy, colostomy, and urostomy. The anatomic location of the stoma provides information about the amount, consistency, and frequency of the output. This information will be used when choosing an appliance to manage the stoma.

A jejunostomy is an opening into the jejunum, which is the midportion of the small intestine. Crohn disease, trauma, or extensive bowel resections may result in a jejunostomy. There is a large amount of intestinal secretions from the jejunum, which aid in digestion. Therefore, the effluent from a jejunostomy is watery, clear, and dark green in color and usually begins within 48 hours after surgery. The volume of output can be over 2 L/day, so it is necessary to monitor the fluid and electrolyte balance for these patients. In addition, the absorption of nutrients, fluids, and electrolytes may be radically reduced in the patient with a jejunostomy. Absorptive capacity of the jejunum depends on the length and function of the proximal bowel. Therefore, nutritional management with hyperalimentation is not uncommon in jejunostomy patients.

An ileostomy is created from the ileum, or the distal portion of the small intestine. The most common reasons for an ileostomy are ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, and familial polyposis. The initial effluent from an ileostomy usually begins within 48 to 72 hours after surgery and is liquid, but may thicken to a mushy consistency once the diet is advanced. In the first few weeks after surgery, the ileostomy output may exceed 1 L/day, resulting in the need to closely monitor fluid and electrolyte balance. Over time, the small bowel adapts and will absorb more fluid,

reducing the volume of output to 500 to 1,000 mL and resulting in thicker stool. The consistency of the output will vary from day to day, depending on the amount of water in the stool.

reducing the volume of output to 500 to 1,000 mL and resulting in thicker stool. The consistency of the output will vary from day to day, depending on the amount of water in the stool.

A colostomy is an opening into a portion of the colon. A colostomy may result from cancer, diverticular disease, volvulus, incontinence, congenital anomalies, or trauma. A stoma may be created in any section of the colon, although cecal and ascending colostomies are rare. The output from the colostomy varies, depending on the stoma location. The more distal the location of the stoma in the colon, the thicker and less frequent the output from the colostomy is. Stoma function also is dependent on the extent of previous bowel resections, residual disease, medications, diet, and concurrent therapies such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

A urostomy is an opening into the urinary tract. Cancer is the most common diagnosis resulting in a urostomy, but incontinence, interstitial cystitis, and congenital anomalies are also the reasons a urostomy may be created. An ileal conduit, colon conduit, and ureterostomy are three types of incontinent urostomies and would require an ostomy appliance to contain the urine. The normal output of urine per day is dependent on fluid intake, but is about 1,000 to 1,500 mL/day.

Health care and the recovery from colon and rectal surgery have dramatically changed in the past years. Hospital stays are decreased, early discharge with follow-up care in the home is on the rise, and insurance coverage and payment restraints affect a person’s ability to control and tailor health care to meet specific needs. All of these factors underline the need to have the patient receive preoperative education. Bass et al. conducted a study that concluded that patients who had preoperative education and stoma site marking by a WOC nurse had fewer stoma complications compared to a group that did not have education.

Preoperative education may include discussion of the proposed surgical option, demonstration of appliances, and description of the type of stoma and how it will be managed. It is helpful to describe the stoma appearance, the usual consistency and quantity of drainage, gas and odor control, diet, fluid and electrolytes, clothing, sexuality, recreation, and return to work.

Stoma Site Marking

There are two factors that are critical to patient satisfaction postoperatively with ostomy care: (a) stoma location and (b) surgeon skill in creating a budded stoma. A poorly sited stoma can increase the chance for appliance leakage and peristomal skin complications, which will further compromise the patient’s adjustment and return to self-care. A well-sited stoma that allows for a secure appliance placement and that does not interfere with the activities of daily living will allow the patient to rapidly gain confidence and adjust to the life with a stoma.

A stoma site should be determined preoperatively for both temporary and permanent ostomies. Although the stoma may be in place only for a few months, difficult appliance management due to poor stoma siting can lead to undue psychologic distress.

There are three factors critical to determining the ostomy site. The location of the site must be (a) within the rectus muscle, (b) outside of abdominal creases and scars, and (c) within the patient’s line of vision. Siting the stoma within the rectus muscle will reduce the risk of hernia formation. Assessment of the abdomen in the supine, sitting, and standing positions is important for detection of changes in body contour. It is also important to have the patient bend at the waist when sitting and standing to evaluate for creases at the site. Bony structures are most evident when the patient is supine. Creases and skin folds are most prominent when the patient is sitting. Visualization of the stoma is very important in being able to return to self-care.

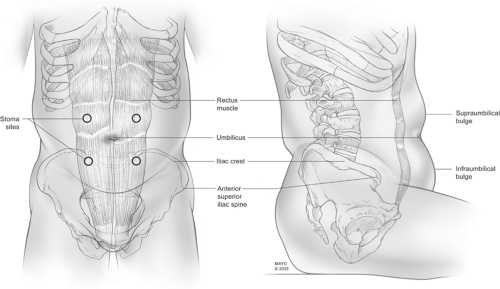

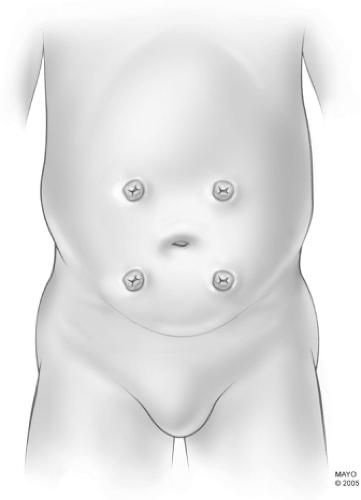

The most commonly accepted practice is to site the stoma on the apex of the infraumbilical bulge using the above three critical factors. Stoma sites in all the abdominal quadrants are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. If a midline incision is used, it is best if the stoma can be located at least two to three fingerbreadths (about 2.5 in.) away from the incision, as this will allow for an adequate barrier to be placed around the stoma postoperatively. In the same manner, it is best to stay at least two to three fingerbreadths away from the iliac crest to avoid interference with appliance adherence. There has been much written in the literature about the controversial issue of marking the stoma site below the belt line. While

most patients report that an ostomy site located below the belt line is easier to conceal within the clothing, the challenge is to find an adequate site in many patients, especially males, who wear their clothing well below the natural waistline of the body. Sites marked too close to the groin crease, too close to the iliac crest, or outside of the patient’s line of vision are fraught with multiple appliance-fit issues. Often a site within the upper quadrant is preferable to the lower quadrant site if the patient can visualize this site and there is an adequate flat surface to adhere the appliance. Sites located within the natural waistline have a strong tendency to crease toward the umbilicus and are not suitable sites for stoma location. To assess for possible creasing of a stoma at a selected site, gently push in and up on the stoma site to visualize the natural tendency of the body to pull back on the bowel. Once the stoma site is located, it should be marked in a manner that will be visible after the surgical scrub. Often the site is marked with an indelible marker and later “scratched” with a sterile needle.

most patients report that an ostomy site located below the belt line is easier to conceal within the clothing, the challenge is to find an adequate site in many patients, especially males, who wear their clothing well below the natural waistline of the body. Sites marked too close to the groin crease, too close to the iliac crest, or outside of the patient’s line of vision are fraught with multiple appliance-fit issues. Often a site within the upper quadrant is preferable to the lower quadrant site if the patient can visualize this site and there is an adequate flat surface to adhere the appliance. Sites located within the natural waistline have a strong tendency to crease toward the umbilicus and are not suitable sites for stoma location. To assess for possible creasing of a stoma at a selected site, gently push in and up on the stoma site to visualize the natural tendency of the body to pull back on the bowel. Once the stoma site is located, it should be marked in a manner that will be visible after the surgical scrub. Often the site is marked with an indelible marker and later “scratched” with a sterile needle.

The ileostomy and ileal conduit are usually sited on the right side, whereas the colostomy is usually sited on the left side. Prosthetic devices, such as braces or belts, must also be assessed and the stoma site is placed for continued use of these devices. When two stomas, such as a colostomy and ileal conduit, are needed, it is best if the stomas can be located on the opposite sides of the abdomen, with sufficient room between them for normal appliance barrier placement. If the rectus muscle needs to be removed for reconstruction reasons, both stomas can be located on the same side, usually one stoma in the lower quadrant and one in the upper quadrant. Adequate peristomal skin margins need to be left around each stoma for placement of the ostomy appliance.

Ideally, postoperative teaching should be a continuation of the teaching already started preoperatively. Postoperative pain and surgical complications can impair the patient’s ability to learn in the hospital setting. Short education sessions are usually better received than one long education session. Shorter hospital stays are prompting more of the ostomy education to be completed in the outpatient setting. Follow-up visits with a WOC nurse or home care nurse should be scheduled before the patient leaves the inpatient setting.

Educational goals should be set with the patient’s input. Although it is ideal for each patient to learn ostomy care to become self-sufficient, many patients cope by having a spouse or family member initially learn the ostomy care. The patient then learns ostomy care at a later date.

Assessment of the patient/family learning styles and barriers is helpful in setting up an educational plan of care. Priority ostomy education focuses on the patient or family member learning how to empty the appliance and to do an appliance change. Upon discharge, the patient or family member should be able to demonstrate an appliance change and how to empty the ostomy appliance. Preoperative teaching, such as diet modification, fluid needs, and activity restrictions, also needs to be discussed.

Many changes occur in the stoma and abdomen within the first 2 to 3 months after surgery. These changes can affect the fit of the ostomy appliance on the abdomen. Also, though the person with an ostomy has had some time to become familiar with the management of the ostomy, s/he may have questions or concerns about how to live a normal life with an ostomy. Teaching can be reinforced, as well as adjustment of the appliance fit and support and encouragement to the person with an ostomy.

Ostomy Appliances

The purpose of an ostomy appliance is twofold: (a) to protect the skin around the stoma from breakdown and (b) to contain the effluent in an odor-proof receptacle. There are numerous products in the market that have been developed to use in ostomy care. Ostomy appliances have three main components that need to be assessed when determining which appliance would work the best: (a) type of skin barrier, (b) type of pouch, and (c) type of pouch closure. The WOC Nurse Standards of Care series states that the average wear time for an ostomy appliance is 3 to 7 days. Generally, patients will change the ostomy appliance one to two times per week.

The skin barrier is the part of the appliance that protects the skin around the stoma. Skin barriers are available in standard wear and extended wear. The difference between these two barriers is in the amount of absorption of the product. The barrier with a delayed absorption provides a longer wear time and is considered an extended wear. A stoma that has a high output or liquid output may get a better seal and skin protection with an extended-wear barrier. As a general rule, colostomies use a standard-wear barrier, whereas ileostomies and urostomies use an extended-wear barrier.

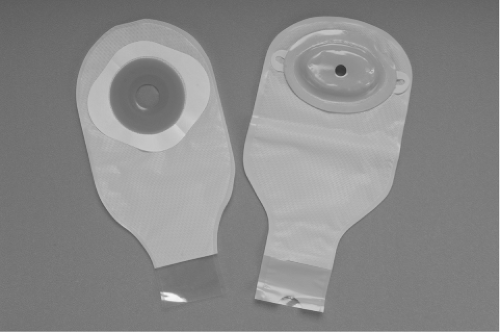

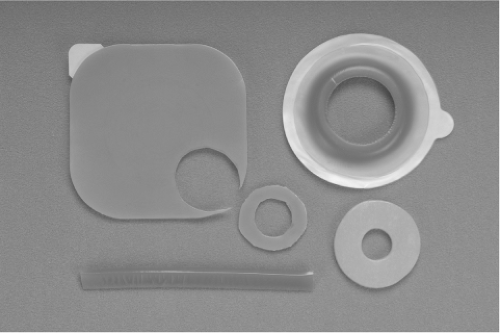

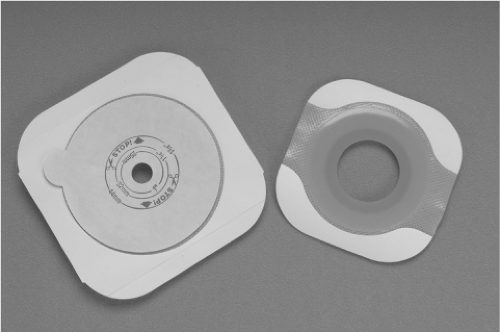

A skin barrier may also be flat or convex (Fig. 3). The peristomal skin plane will determine which type of barrier to use. The shape of the skin barrier should mirror the peristomal skin plane. Therefore, if there is retraction of the skin around the stoma, a convex skin barrier may be used. There are many additional skin barrier products that can be used on a skin barrier to provide all types of convexity (Fig. 4).

The skin barrier is available in cut-to-fit and precut options (Fig. 5). If the stoma is not completely round or is changing size in the immediate postoperative period, a cut-to-fit option may be the best. For the patient with limited dexterity, the precut option may be used.

Skin barriers also come in paste and liquid forms. Paste is used as a caulk on the back of a solid skin barrier to fill in irregular areas. It should be noted that some pastes contain alcohol, which may cause temporary burning of denuded skin and will usually dissolve in 1 to 2 days due to contact with the effluent. For this reason, paste is not often used. Liquid and powder skin barriers may be used under a solid skin barrier to provide skin care to the denuded skin (Fig. 6).

The pouch or “bag” is the part of the appliance that holds the effluent. Pouches are usually made from an odor-proof plastic. They are available in many shapes and sizes, and are either transparent or opaque. A pouch needs to be emptied when it becomes one-third to one-half full of gas or effluent.

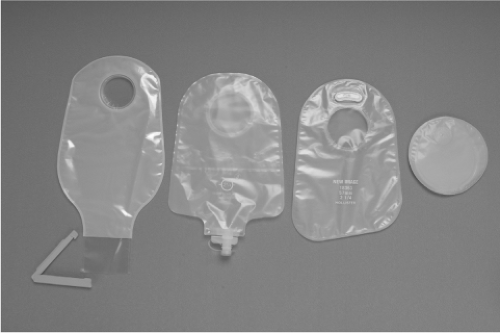

The pouches come in three main styles: (a) drainable, (b) urinary, and (c) closed end (Fig. 7). The drainable pouch is used for fecal effluent. The effluent is drained out of the bottom of the pouch without having to remove the appliance from the body. The opening at the bottom is secured with a clamp or closure. The urinary pouch is used for urine and has a tap that can be easily opened to drain the urine from the bottom of the pouch without having to remove the appliance from the body. A closed-end pouch has no opening and must be removed either from the body or from the skin barrier to be emptied. This type of pouch is often used with a descending or sigmoid colostomy, when the stool is most often formed. Additional features on pouches may be gas filters, cloth covers, or belts that help secure the appliance to the body.

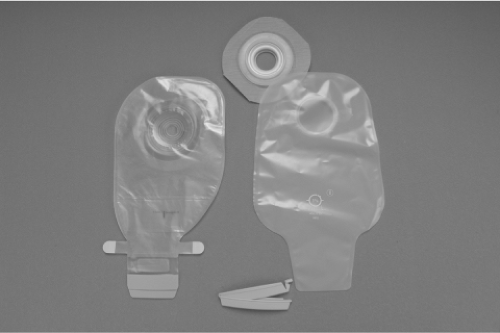

An ostomy appliance can be categorized as either one piece or two piece (Fig. 8). A one-piece appliance has both the skin barrier and the pouch in one unit. This appliance may be more flexible and has a lower profile on the body. A two-piece appliance

has a skin barrier or wafer that is separate from the pouch. The two-piece appliance has the advantage that the stoma can be viewed more clearly when placing the wafer. Also, different types of pouches can be used without changing the wafer (i.e., closed-end pouch, opaque pouch, etc.).

has a skin barrier or wafer that is separate from the pouch. The two-piece appliance has the advantage that the stoma can be viewed more clearly when placing the wafer. Also, different types of pouches can be used without changing the wafer (i.e., closed-end pouch, opaque pouch, etc.).

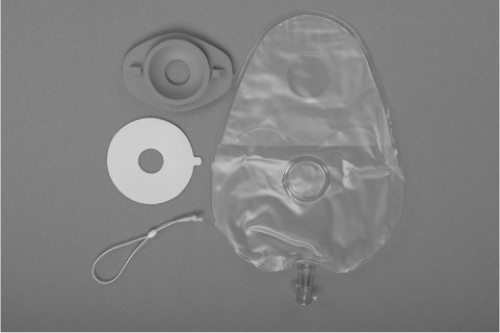

A disposable appliance is constructed of a lightweight, odor-proof material and is made to be thrown away after normal use (3 to 7 days). The majority of patients with an ostomy use this type of an appliance. A reusable appliance (Fig. 9) is made from a more durable material (rubber or heavy plastic) and tends to be much heavier, often requiring the extra support of a belt to hold it in place. This appliance often needs additional adhesives to properly seal it to the body. The reusable appliance still needs to be changed every 3 to 7 days, and requires additional maintenance as it needs to be cleaned between each use. A reusable appliance can be more cost-effective for the long-term use.

Peristomal Skin Care

The skin around an ostomy should look the same after surgery as it did before surgery. Basic principles in the management of peristomal skin are to thoroughly wash and dry the skin before applying a properly fitted appliance. The fewer products used on the skin, the lesser is the chance for skin problems.

The appliance should be removed carefully from the peristomal skin. When lifting the edge of the skin barrier, it is best to push down on the skin of the abdomen, to pull it away from the skin barrier. Warm water or an adhesive remover may also be used. It is important to wash the skin well with warm water to remove any adhesive remover residue, which may cause skin irritation or prevent the appliance from adhering to the skin.

When cleaning peristomal skin, it is best to use only warm water and a soft cloth or paper towel and dry well. If soap or skin cleanser is used, it is important to wash the skin well with clean water before applying the appliance in order to remove any residue on the skin. Products containing alcohol should be avoided due to the dehydrating effect on the skin, which may result in flaking, itching, and breakdown of the epithelial layer of the skin. Conversely, products with an oil or petroleum base will leave an oily residue on the skin, which may affect appliance adherence. It is not unusual to notice a small amount of blood on the cloth when washing around the stoma. The bowel mucosa contains small blood vessels and may bleed when the area is cleaned.

Fig. 9. Reusable appliance: Rubber faceplate, double-sided adhesive (secures faceplate to the skin), bead O-ring (which secures the pouch to the rubber faceplate), and urinary pouch. |

Excessive peristomal hair should be removed from the peristomal skin to promote a better appliance seal. Some people shave with an electric razor or with a safety razor, using an ostomy skin barrier powder for a dry shave or mild soap and water for a wet shave. When shaving with a razor, use care not to damage the stoma or skin. Hair also may be clipped close to the skin using a scissors.

The practice of using antacids to treat skin irritation is no longer recommended. Antacids alter the pH level of the skin, which may potentiate further skin breakdown.

The best form of skin protection is an appropriately fitted appliance. If skin problems are present, it is important to determine the cause. This is necessary to appropriately treat the skin. The most common cause of peristomal skin irritation is stool in contact with the skin. The appliance opening should be no more than one-eighth inch larger than the stoma.

Skin irritation is treated with a skin barrier powder, which is sprinkled sparingly on the peristomal skin. Any excess powder is brushed off the skin. A non-alcohol-based skin sealant can be applied over the powder to help ensure a good appliance seal. The skin sealants are available in sprays, wipes, or gels. After the skin sealant is dry on the skin, the appropriate size and style of appliance can be applied.

At the first sign of leakage, which may be indicated by itching, burning, or pain at the ostomy site, the entire appliance must be changed. Treatment of peristomal skin breakdown will be further discussed under peristomal skin complications.

Flatus and Odor

A major concern of ostomy patients is the passage of flatus through the stoma. The passage of flatus through the stoma may make noise similar to the passage of flatus through the anal opening. Layers of clothing will help “muffle” the sound. Causes of intestinal flatus are smoking, chewing gum, use of straws, skipping meals, emotional upset, and gas-forming foods (Table 1). Simethicone can be used to reduce the amount of flatus. A filter on the pouch may reduce the profile of the pouch by filtering the gas while eliminating the odor.

Table 1 Properties of Various Foods | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Most of the fecal ostomy pouches are odor-proof for up to 7 days. Odor that is apparent from the appliance would be an indicator of leakage under the skin barrier. If the end of a drainable pouch is not properly cleansed, then also odor can result. Some foods also increase the odor of the effluent (Table 1). Oral preparations containing chlorophyll (200 to 400 mg) and bismuth

subgallate (400 mg) may be used to decrease the odor of the stool in the intestine. In-pouch deodorants are also available to eliminate the odor of the stool in the pouch. The appliance should be changed immediately when odor is detected.

subgallate (400 mg) may be used to decrease the odor of the stool in the intestine. In-pouch deodorants are also available to eliminate the odor of the stool in the pouch. The appliance should be changed immediately when odor is detected.

Diet and Fluids

There are no dietary restrictions for a person with an ostomy. Postoperatively, there may be short-term restrictions for 2 to 6 weeks on fibrous foods due to intestinal edema. Colon surgery usually results in 2 weeks of diet restriction, whereas with small intestine surgery the restrictions are increased to 6 weeks. Certain foods have been shown to affect the bowel in various ways (Tables 1 and 2). Manipulation of the diet can assist in “thickening” or “thinning” the stool output, or decreasing gas and odor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree