Patient Story

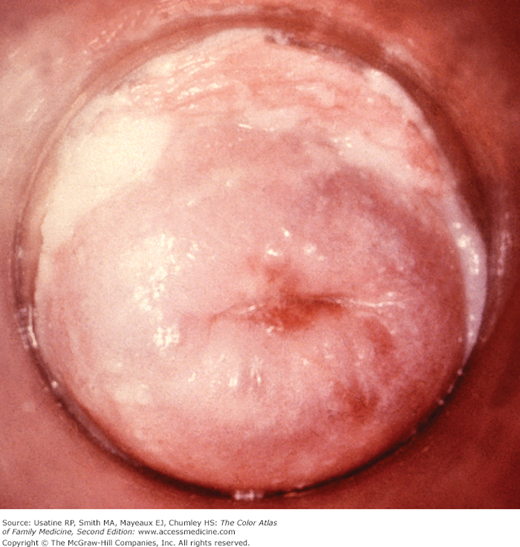

A 35-year-old woman presents with severe vaginal and vulvar itching. She also complains of a thick white discharge. Figure 83-1 demonstrates the appearance of her vagina and vulva while Figure 83-2 shows her cervix. Figure 83-3 shows her wet prep. Treatment with a nonprescription intravaginal antifungal preparation was successful.

Introduction

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is a common fungal infection in women of childbearing age. Pruritus is accompanied by a thick, odorless, white vaginal discharge. VVC is not a sexually transmitted disease. On the basis of clinical presentation, microbiology, host factors, and response to therapy, VVC can be classified as either uncomplicated or complicated.1 Uncomplicated VVC is characterized by sporadic or infrequent symptoms, mild-to-moderate symptoms, and the patient is nonimmunocompromised. Complicated VVC is characterized by recurrent (four or more episodes in 1 year) or severe VVC, non-albicans candidiasis, or the patient has uncontrolled diabetes, debilitation, or immunosuppression.1

Epidemiology

- VVC accounts for approximately one third of vaginitis cases.1

- Candida species are part of the lower genital tract flora in 20% to 50% of healthy asymptomatic women.2

- Seventy-five percent of all women in the United States will experience at least one episode of VVC. Of these, 40% to 45% will have two or more episodes within their lifetime.3 Approximately 10% to 20% of women will have complicated VVC that necessitates diagnostic and therapeutic considerations.

- It is a frequent iatrogenic complication of antibiotic treatment, secondary to altered vaginal flora.

- Nearly half of all women experience multiple episodes, and up to 5% experience recurrent disease.1

- Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) is defined as four or more episodes of symptomatic VVC in 1 year. It affects a small percentage of women (<5%).4 Recurrent yeast vaginitis is usually caused by relapse, and less often by reinfection. Recurrent infection may be caused by Candida recolonization of the vagina from the rectum.5

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Most vulvovaginal Candidiasis is caused by Candida albicans (Figure 83-3).1,6 Candida glabrata now causes a significant percentage of all Candida vulvovaginal infections. This organism is resistant to the nonprescription imidazole creams. It can mutate out of the activity of treatment drugs much faster than albicans species.7

- The disease is suggested by pruritus in the vulvar area, together with erythema of the vagina and vulva (Figures 83-1 and 83-2). The familiar reddening of the vulvar tissues is caused by an ethanol by-product of the Candida infection. This ethanol compound also produces pruritic symptoms. A scalloped edge with satellite lesions is characteristic of the erythema on the vulva.

- VVC can occur concomitantly with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

- The pathogenesis of recurrent VVC is poorly understood, and most women with these recurrences have no apparent predisposing or underlying conditions.1

Risk Factors

- Diabetes mellitus.8,9

- Recent antibiotic use.

- Increased estrogen levels.

- Immunosuppression.

- Contraceptive devices (vaginal sponges, diaphragms, and intrauterine devices).

- Genetic susceptibility.

- Behavioral factors—VVC may be linked to orogenital and, less commonly, anogenital sex.

- Wearing diapers.

- Spermicides are not associated with Candida infection.

- There is no high-quality evidence showing a link between VVC and hygienic habits or wearing tight or synthetic clothing.

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis is usually suspected by characteristic findings (Figures 83-1 and 83-2). Typical symptoms include pruritus, vaginal soreness, dyspareunia, and external dysuria. Typical signs include vulvar edema, fissures, excoriations, or thick, curdy vaginal discharge.1

- Vaginitis solely caused by Candida generally has a normal vaginal pH of less than 4.5.

- The wet prep, KOH smear, or Gram stain may demonstrate yeast and/or pseudohyphae (Figures 83-3 and 83-4). Wet preps may also demonstrate white blood cells, trichomonads, candidal hyphae, or clue cells.

- The KOH prep is made by adding a drop of KOH solution to a drop of saline suspension of the discharge. The KOH lyses epithelial cells in 5 to 15 minutes (faster if the slide is warmed) and allows easier visualization of candidal hyphae or yeast.1 Swartz-Lamkins stain (potassium hydroxide, a surfactant, and blue dye) may facilitate diagnosis by staining the yeast organisms a light blue.10

- Rapid antigen testing is also available for Candida. The detection of vaginal yeast by rapid antigen testing is feasible for office practice and more sensitive than wet mount. A negative test result, however, was not found to be sensitive enough to rule out yeast and avoid a culture.6 SOR A

- Fungal culture with Sabouraud agar, Nickerson medium, or Microstix-Candida medium should be considered in patients with symptoms and a negative KOH because C. glabrata

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree