INTRODUCTION

CASE 16-1

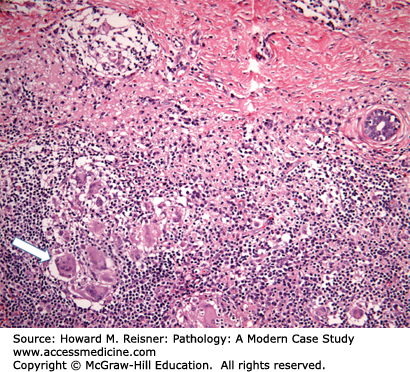

A 32-year-old G4P4 woman presents with complaints of a new lump in her left breast. Her past medical history is negative for a family history of breast carcinoma. Physical examination reveals a 3 cm firm, ill-defined mass that is tender to palpation. Ultrasound studies demonstrate a 4 cm solid-appearing mass with ill-defined borders. Due to the solid-appearing nature of the lesion and ill-defined borders, the lesion is categorized as suspicious and biopsy is recommended. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is performed yielding the histology demonstrated in Figure 16-1.

Pathologic diagnosis: Granulomatous mastitis.

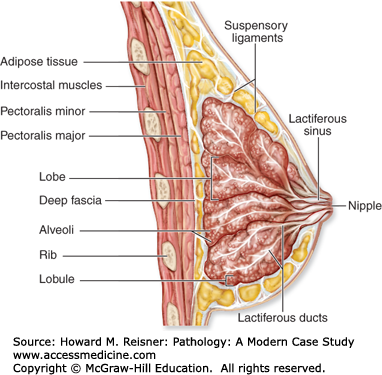

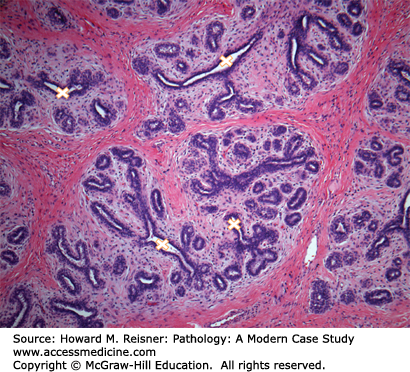

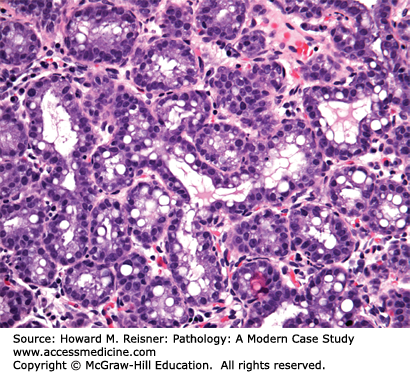

The breast lies anterior to the chest wall over the pectoralis major muscle and typically extends from the second to the sixth rib in the vertical axis and from the sternal edge to the midaxillary line in the horizontal axis. Bundles of dense fibrous connective tissue, the suspensory ligaments of Cooper, extend from the skin to the pectoral fascia and provide support for the breast. At puberty, estradiol and progesterone levels increase to initiate breast development. The adult female breast consists of a series of branching ducts that terminate in lobules. The arrangement of these structures resembles a branching tree with 5–10 primary milk ducts in the nipple, 20–40 segmental ducts, and 10–100 subsegmental ducts that end in glandular units called terminal-duct lobular units (TDLU) (Figure 16-2). The TDLU represents the functional unit of the breast (Figure 16-3). During lactation, there is a dramatic increase in the number of lobules, and the epithelial cells in the TDLU undergo secretory changes consisting of cytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 16-4). The accumulated secretions are then transported via the ductal system to the nipple. When lactation ceases, the lobules involute and return to their normal resting appearance. The mammary ducts and lobules are embedded within a stroma composed of varying amounts of fibrous and adipose tissue. The stromal component comprises the major portion of the nonlactating adult breast, consisting of lobular stroma and interlobular stroma. The proportions of fibrous and adipose tissue vary with age and among individuals and may affect the sensitivity and specificity of mammographic studies. During menopause, as a result of reduction in estrogen and progesterone, there is involution and atrophy of the TDLUs associated with loss of the specialized intralobular stroma. The postmenopausal breast is characterized by marked reduction in the glandular and fibrous stroma components, typically with concomitant increase in stromal adipose tissue.

FIGURE 16-2

Anatomy of the breast (diagrammatic sagittal section). The ductal system extends from the nipple to multiple lobes of terminal-duct lobular units (TDLUs) branching in a treelike fashion. The TDLU is the site of origin for most breast carcinomas. The ducts and lobular acini are lined by two layers of cells: the inner luminal cells and outer myoepithelial cells. (Reproduced with permission from McKinley M, O’Loughlin VD. Human Anatomy, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.)

The cells lining the ductal-lobular system are bilayered. The inner luminal cell layer is cuboidal to columnar in shape and typically shows relatively uniform round nuclei. Most pathologic epithelial lesions of the breast, including carcinoma, arise from the luminal cell layer. The outer myoepithelial (basal) cell layer is typically comprised of flattened-appearing cells with compressed nuclei and scant cytoplasm. It is critical to understand this concept as preservation or loss of this bilayered arrangement is used to distinguish benign from malignant epithelial lesions of the breast (Figure 16-5).

FIGURE 16-5

Myoepithelial cells. Myoepithelial cells surround all of the ducts and lobules of the breast and are preserved in cases of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (A) as highlighted here by an immunohistochemical stain for p63. The myoepithelial cell nuclei stain brown. In contrast, invasive carcinomas show infiltration into the breast stroma with loss of the myoepithelial cell layer (B). A small focus of normal breast tissue with surrounding myoepithelial cells highlighted by smooth muscle actin immunostain is present in the center of the image.

The various presenting clinical symptoms of breast disease are summarized in Table 16-1. These symptoms include breast mass/lump, breast pain, nipple-related problems, and skin changes. Breast mass/lump is the most common presenting symptom. Each symptom should bring to mind a differential diagnosis depending on the clinical context. Benign conditions predominate in younger patients and breast cancer becomes increasingly more prevalent with advancing age. Breast cancer does not have specific signs and symptoms that allow reliable distinction from the various benign breast conditions. Breast abnormalities often require thorough clinical examination, imaging studies, and tissue sampling (biopsy) for definitive classification of disease. In asymptomatic women, abnormal findings on screening breast imaging are a common cause of referral to breast clinic and tissue biopsy for diagnosis.

| Symptom or Finding | Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Discrete lump | |

| Age <30 | Fibroadenoma Cyst (fibrocystic change) Intramammary lymph node Inflammatory lesions Fat necrosis Inflammatory lesions Hereditary breast carcinoma (rare) |

| Age 30–50 | Cyst (fibrocystic change) Fibroadenoma Carcinoma Inflammatory lesions Fat necrosis |

| Age >50 | Carcinoma Cyst (fibrocystic change) Fat necrosis Fibroadenoma |

| Other rare | Phyllodes tumor Fibrous mastopathy Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia |

| Diffuse lumpiness | Fibrocystic change |

| Indiscrete lump | Fibrocystic change (fibrosis) Normal breast tissue Inflammatory lesions Carcinoma (especially lobular) |

| Breast pain | |

| Cyclic | Hormone related |

| Noncyclic | Inflammatory conditions Fat necrosis related to trauma Cyst (fibrocystic change) Carcinoma |

| Nipple discharge | |

| Galactorrhea | Hyperprolactinemia, hypothyroidism, drugs |

| Single duct (bloody) | Intraductal papilloma Carcinoma |

| Single duct (nonbloody) | Fibrocystic change Duct ectasia |

| Nipple changes | |

| Erythema/scaling | Dermatitis Paget disease |

| Skin changes | |

| Erythema | Inflammatory dermatologic condition Inflammatory breast carcinoma |

| Induration/dimpling | Inflammatory conditions Carcinoma Fat necrosis |

WHAT WE DO Clinical Evaluation of Breast Disease

Breast abnormalities are usually evaluated with “triple assessment” including physical examination, imaging studies, and tissue sampling for suspicious or indeterminate breast lesions. Key aspects of physical examination include palpation of the four quadrants of the breast, palpation of axilla for enlarged lymph nodes, examination of breast skin/areola/nipple, and evaluation of nipple discharge. Most mass lesions in women >35 years of age are evaluated with mammography, often in conjunction with ultrasound studies. The advantage of mammography as an imaging modality is that it is quick to perform and interpret its images essentially the whole breast and has a reasonably high sensitivity to detect invasive carcinoma (identified as density, architecture distortion or asymmetry) and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (calcifications). It is important to understand that not all cancers are seen using mammography and that palpable masses not identified on imagines studies still require further investigation. Approximately 10% of breast cancers are mammographically occult. Ultrasound may assist in the identification of palpable masses and densities detected by mammography. Ultrasound is particularly useful in determining whether a lesion is solid or cystic. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful in certain clinical situations in the detection of breast cancer. These include patients at high risk of the development of breast cancer and dense breast tissue, local staging of breast cancer prior to breast conserving therapy, and identification of occult breast cancers in patients presenting with metastatic carcinoma within axillary lymph nodes. While MRI demonstrates high sensitivity, a drawback of MRI is lower specificity. Several benign lesions may have a worrisome appearance by MRI evaluation. The optimal utilization of MRI studies is a source of controversy and ongoing research.

Breast lesions that are indeterminate or suspicious by imaging studies typically undergo biopsy evaluation in which a small piece of the lesion is removed and evaluated in surgical pathology for definitive classification of the lesion. A list of the various types of breast biopsies is provided in Table 16-2. Solid lesions are usually biopsied under ultrasound guidance using a large cutting needle with a spring-loaded, automated biopsy instrument to obtain tissue specimens for histologic evaluation. Biopsies taken in this manner are called core biopsies. Ultrasound cores are typically 1–2 cm in length and 1–2 mm in thickness depending on the gauge of needle used. Biopsy of calcifications requires the use of stereotactic guidance to ensure sampling of the calcifications in the core biopsy tissue. Most of the stereotactic biopsies are performed with vacuum-assisted systems using a 14, 11, or 8 gauge needle, allowing multiple core samples to be taken to help ensure thorough sampling of the breast tissue in the region of concern. The core biopsy tissues are then evaluated in the pathology lab using light microscopy and a report is generated listing the pathologic diagnoses. Lastly, fine-needle aspiration technique using a 22–25 gauge needle may also be used in certain clinical situations, such as cyst evaluation. Fine-needle aspirations remove individual cells that are then smeared on a slide to be evaluated by a pathologist. Cyst aspirations yielding bloody fluid are one example in which pathologic evaluation of the fluid is recommended to exclude malignancy.

| Specimen Type | Indications |

|---|---|

| Core biopsy | Standard biopsy used to evaluate most breast abnormalities |

| Ultrasound core | Solid masses/nodules/densities |

| Stereotactic core | Calcifications, tiny nodules, architecture distortion |

| Fine-needle aspiration | Cysts Some inflammatory lesions |

| Excisional biopsy | Complete excision of lesion/region of concern Used in breast conserving therapy (BCT) Discordance between imaging and core biopsy results |

| Lumpectomy | Complete excision of a mass lesion Used in breast conserving therapy (BCT) |

| Mastectomy | Failure to achieve negative margins with BCT Large/multicentric malignancy not amendable to BCT Hereditary breast cancer Patient preference |

It is essential that all pathologic diagnoses are correlated with the imaging findings to ensure adequate sampling of the lesion of concern. In some cases, such as a particularly small or poorly defined nodule, the core biopsy may miss the target resulting in a false negative study. Pathologic–radiographic correlation helps identify these rare cases such that repeat tissue sampling can be performed.

BENIGN BREAST DISEASE

Most cases of granulomatous mastitis represent an idiopathic granulomatous inflammatory process, typically occurring in parous women between the ages of 20 and 40 (Case 16-1). The idiopathic form has been designated granulomatous lobular mastitis. Systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis and Wegener granulomatosis and atypical infections from fungi and mycobacteria may also rarely cause granulomatous mastitis and should be clinically excluded. Women with granulomatous lobular mastitis may present with a breast mass that is suspicious for malignancy by imaging studies. The characteristic non-necrotizing granulomas are typically centered on the lobules and associated with few background neutrophils and lymphocytes.

Acute mastitis is an inflammatory condition characterized by a neutrophilic response to bacteria, often Staphylococcus aureus or streptococci. Most cases are associated with breastfeeding secondary to the development of cracks and fissures in the nipple allowing bacteria to enter the breast tissue. Patients typically present with breast pain and erythema. Most cases of acute mastitis are successfully treated with antibiotics, only rarely requiring surgical incision and drainage.

Unlike acute mastitis, this inflammatory condition that may become chronic is not associated with lactation, but strongly associated with tobacco smoking. Nipple piercing complications may also result in subareolar abscess formation. This condition is characterized by squamous metaplasia of the major lactiferous ducts of the nipple resulting in duct obstruction from keratinous debris, duct rupture, and an intense inflammatory response to the ruptured ducts contents. Patients often present with an inverted nipple and a painful subareolar mass. A fistula tract develops in recurrent cases necessitating surgical excision of the involved ducts and fistula tract.

This condition is often identified in patients with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus or autoimmune disease, suggesting an underlying autoimmune etiology Case 16-2. The lesions, which may be multiple, are characterized by dense collagenous stroma associated with mild periductal and perivascular chronic inflammation. Patients present with a firm breast mass or masses. Imaging studies often reveal an indeterminate mass requiring biopsy evaluation.

CASE 16-2

A 45-year-old woman presents with complaints of a firm breast lump present over the last 4 months. Her past medical history is significant for type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Physical examination reveals a fairly discrete, very firm mass in the right breast. The mass is not tender on palpation. Mammographic and ultrasound studies reveal a dense solid mass with focally ill-defined borders. The lesion is categorized as suspicious and biopsy is recommended. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is performed yielding the histology demonstrated in Figure 16-6.

Pathologic diagnosis: Dense stromal fibrosis with periductal and perivascular chronic inflammation, consistent with fibrous mastopathy.

CASE 16-3

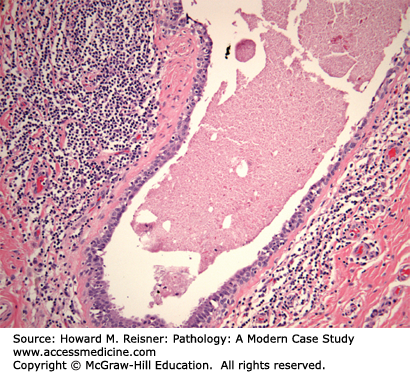

A 48-year-old woman presents with a 1 cm ill-defined breast lump located in the subareolar region of the left breast. The patient also reports a history of thick proteinaceous nipple secretions without blood from the left breast. Her past medical history is unremarkable. Ultrasound evaluation reveals a cystically dilated duct with thick walls favoring a benign process. The patient desires to have the lesion excised and an excisional biopsy of the lesion is performed yielding the histology demonstrated in Figure 16-7.

Pathologic diagnosis: Duct ectasia.

CASE 16-4

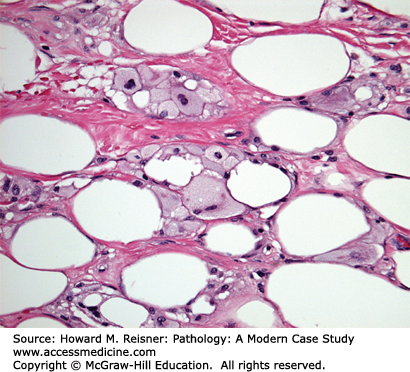

A 64-year-old woman presents with complaints of a new 5 cm firm breast mass. The patient’s past medical history is remarkable only for hypertension with no family history of breast cancer. Physical examination reveals a large firm mass measuring at least 5 cm. Mammographic and ultrasound imaging reveals a solid density with irregular margins categorized as highly suspicious for malignancy. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy is performed yielding the histology demonstrated in Figure 16-8. After obtaining the diagnosis, further questioning reveals that the patient was in a motor vehicle accident 3 months earlier resulting in trauma to her chest region.

Pathologic diagnosis: Fat necrosis.

Duct ectasia Case 16-3 is characterized by dilated ducts filled with thick proteinaceous material and numerous lipid-laden macrophages. The periductal stromal often contains a mild infiltrate of lymphocytes surrounding the involved ducts. The ducts may rupture in some cases eliciting a more intense inflammatory response and associated fibrosis. Patients typically present with an ill-defined breast mass.

HUNTING FOR ZEBRAS

Fat necrosis Case 16-4 is important to consider in women who have had breast trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accident) or prior breast surgery and present with a breast mass. History of breast trauma should be elicited during the evaluation of a new breast mass. These lesions may closely mimic a breast carcinoma, both on physical examination and on imaging studies. Microscopically, acute lesions are often paucicellular consisting of necrotic adipose tissue. As these lesions begin to organize, inflammatory cells, lipid-laden macrophages, and fibrosis become apparent. Dystrophic calcifications may form in older lesions.

CASE 16-5

A 28-year-old woman presents with complaints of a new lump in her left breast that has been present for several months. The patient became concerned when she developed breast pain associated with the mass. She is concerned that the mass could be breast cancer. The patient’s past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. There is no family history of breast cancer. Physical examination reveals diffusely dense firm breasts with vague nodularity and a discrete, circumscribed, tender 1 cm nodule in the left breast. Ultrasound evaluation reveals a cystic lesion in the palpable area of concern. Needle aspiration of the cyst is performed yielding clear serous fluid. Following aspiration, the mass is no longer palpable. The patient is reassured that the lesion is a benign cyst and in this clinical context, the findings are consistent with fibrocystic change. Needle-localized excisional biopsy of the remaining calcifications was subsequently performed revealing similar findings. No carcinoma was identified.

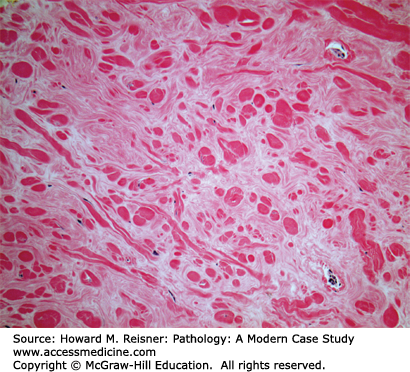

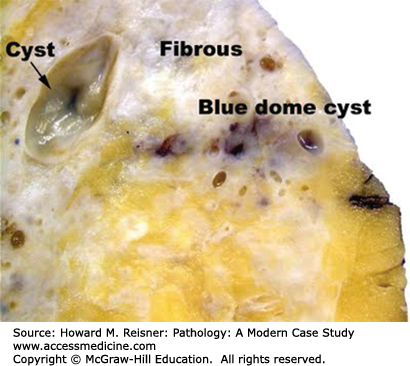

Fibrocystic change Case 16-5 is extremely common, with more than one-third of females between the ages of 20 and 45 years of age showing some evidence of this condition on physical examination. Fibrocystic change of the breast includes a wide variety of changes of the breast ducts and stroma resulting in “lumpy” change of the breasts on physical examination. Gross examination of breast tissue involved by fibrocystic change reveals dense white stromal tissue admixed with variably sized cysts that may have a brown or blue (blue-dome cyst) discoloration (Figure 16-9). Microscopically these changes entail fibrosis of the breast stroma, cystic dilation of ducts, apocrine metaplasia, adenosis, and variable degrees of usual-type ductal epithelial hyperplasia (Figure 16-10). These changes are further classified as nonproliferative and proliferative fibrocystic change depending on the degree of ductal hyperplasia present. Nonproliferative fibrocystic change is not associated with increased risk of breast cancer, while proliferative fibrocystic change is associated with slight increased risk of breast cancer (1.5–2.0× increased relative risk). Cases of proliferative fibrocystic change typically show an intraductal proliferation of luminal and myoepithelial cells that may fill and distend the duct lumen. The cysts and nodular areas of dense stromal sclerosis presenting as breast masses in patients may require further evaluation to exclude breast cancer. Microcalcifications are often associated with fibrocystic change, observed in association with apocrine metaplasia, adenosis, and cysts. These microcalcifications may require sampling if their appearance on mammogram is suspicious.