Breast and Sentinel Node

Rebecca J. Wolsky

Jerome B. Taxy

Introduction: Breast Frozen Section

The historical importance of the breast frozen section in the evolution of surgical pathology practice is the basis for including this topic. The paradigm for clinically relevant immediate decision making in surgical pathology as well as the practical history of intraoperative diagnosis can both be illustrated by the implementation of frozen section related to breast cancer. In the current era, a decline in the number of frozen section diagnoses in the management of breast cancer is a reflection of the significant changes in the clinical detection and therapy of this disease over the last approximately 40 years.

In the premammography era, breast tumors were discovered by palpation, usually by the patient herself or her spouse, partner, or physician. The definitive diagnosis was made by open biopsy, incisional or excisional. While the patient was still anesthetized, a fresh tissue sample, even if grossly benign, was sent to the surgical pathology laboratory for immediate analysis by frozen section. If the frozen section showed carcinoma in any form, in situ or invasive, a mastectomy was immediately done. Since mastectomy was the only therapeutic option, the objective of this sequence was to provide definitive therapy without a second anesthesia. In the later years in which this practice was common, fresh samples of invasive tumors, 0.5 to 1 g, were submitted for estrogen receptor determination, which was done by competitive binding assay. Because tumors were relatively large and biopsy samples were of generous size, there was typically ample tumor to spare.

The advent of screening mammography in the 1970s and subsequent generations of refined imaging techniques have been major factors in changing both the histologic evaluation and therapeutic approach to breast cancer by detecting tumors of small size. The size of the tumors is perhaps best summarized by a premammography era tabulation of 1,355 cases seen at the Memorial Hospital in New York from 1935 to 1942, where more than half the tumors were between 2 and 4 cm and almost 20% were larger than 5 cm (1). In the current era, most tumors are smaller than 2 cm and many are not palpable at all. Diminished tumor size is encountered in both community hospitals as well as referral settings. Table 8.1 illustrates the comparable sizes of invasive breast cancers as encountered at the time of

diagnosis over several recent years at the Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, a large community hospital in the Chicago suburbs, and the University of Chicago (data supplied by the Cancer Registries in the respective institutions). The decrease in size of the tumors is largely due to screening mammography, which has concomitantly solidified the concept of breast-conservation surgery. The combination of the accepted efficacy of conservation procedures coincident with the radiographic discovery of smaller tumors and the emergence of varied systemic therapies has changed the treatment algorithm for this disease.

diagnosis over several recent years at the Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, a large community hospital in the Chicago suburbs, and the University of Chicago (data supplied by the Cancer Registries in the respective institutions). The decrease in size of the tumors is largely due to screening mammography, which has concomitantly solidified the concept of breast-conservation surgery. The combination of the accepted efficacy of conservation procedures coincident with the radiographic discovery of smaller tumors and the emergence of varied systemic therapies has changed the treatment algorithm for this disease.

Table 8.1 Size of Invasive Breast Cancer in Community and University Setting | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Small size is a major disadvantage for frozen section diagnosis for several reasons: (1) the risk of having to freeze the whole tumor which could represent the entirety of the patient’s disease, (2) the introduction of both frozen and paraffin-embedded artifacts, (3) receptor status must be established on formalin fixed paraffin-embedded tissue, (4) there is no emergent therapeutic decision to be made. Therefore, the diagnosis of breast carcinoma is now rarely established by frozen section, but instead by core needle biopsy or aspiration cytology. Immediate definitive surgery is unusual as the patient herself is sure to be consulted about the therapeutic options after the diagnosis. Consequently, the number of breast frozen sections has markedly diminished (2). At the University of Chicago, in 2011, only seven breast tissue specimens were sent for intraoperative diagnosis. Yet, the need to recognize breast cancer by frozen section remains current, primarily as applied to metastatic sites (see below).

The Breast Frozen Section: Major Intraoperative Questions

Current published studies on breast frozen sections are uncommon (3,4,5,6). It is perhaps of some relief to pathologists that legal actions related to breast cancer are relatively few for frozen section (7), with the legal burden,

in general, having been shifted to the radiologists (8). While the prior habit of freezing all breast specimens is no longer advocated (9), in the context of individualizing therapy there is an occasional request for a frozen section of a breast mass. Though the circumstances are exceptional, the major question has not changed, that is, to definitively and immediately identify a malignant tumor. The price that has been paid for decreased frequency is that the pathologist is less experienced and perhaps not as confident as in the past. In an attempt to minimize error therefore, interpreting a breast frozen section may negatively influence the therapeutic goal by resulting in a deferred diagnosis or a descriptive nondiagnostic response.

in general, having been shifted to the radiologists (8). While the prior habit of freezing all breast specimens is no longer advocated (9), in the context of individualizing therapy there is an occasional request for a frozen section of a breast mass. Though the circumstances are exceptional, the major question has not changed, that is, to definitively and immediately identify a malignant tumor. The price that has been paid for decreased frequency is that the pathologist is less experienced and perhaps not as confident as in the past. In an attempt to minimize error therefore, interpreting a breast frozen section may negatively influence the therapeutic goal by resulting in a deferred diagnosis or a descriptive nondiagnostic response.

Occasionally, a request may be received for intraoperative assessment of margins on a definitive lumpectomy specimen. The immediate consequence of such evaluations would be a margin re-excision, with possible conversion to a complete mastectomy. Although immediate margin assessment is not a common practice among surgeons and pathologists, and is not performed at the University of Chicago, it is a subject of active discussion. Given the high fat content of such specimens, a frozen section is difficult to execute and interpret, especially related to atypical proliferations at the margins perhaps additionally altered by cautery artifact. Techniques such as freezing with liquid nitrogen have been attempted in this regard (10).

Beyond the technical difficulties, though, are important conceptual considerations (11). First, borderline cytologic and architectural atypia in any part of the sample may be difficult to evaluate even with well-prepared paraffin sections. Trying to do this on a frozen section may be ill advised. Second, no majority consensus currently exists as to what constitutes a clean margin. The range may vary from 1 to 5 mm for invasive carcinoma. Given the lack of rigidity of the tissue and its propensity to shrink, such precise measurements are even more difficult to make on a frozen section evaluation. Last, in this era of improved systemic therapy, the very emphasis on complete surgical removal of microscopic residual tumor is being called into question. For now, the optimal evaluation for breast-conservation specimens under intraoperative conditions requires a good gross assessment; actual frozen sections should be used judiciously (3,4). Definitive microscopic examination should be done on inked, well-fixed, and processed tissue. The decision for margin re-excision can then take into account other information including imaging, lymph node status, and plans for adjuvant therapy.

The Breast Frozen Section and its Interpretation

The most important parameter in the analysis of a breast frozen section is the gross examination. The specimen should be inked according to departmental practice and all sectioned surfaces should be inspected to minimize sampling error (Fig. 8.1, e-Fig. 8.1). To minimize potential artifacts, the freezing of fatty areas should be avoided; the need for sharp blades and cryostats for which the temperature is properly monitored and maintained, cannot be overstated. The histologic examination of the actual

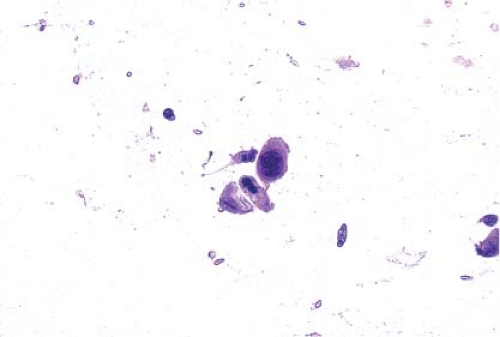

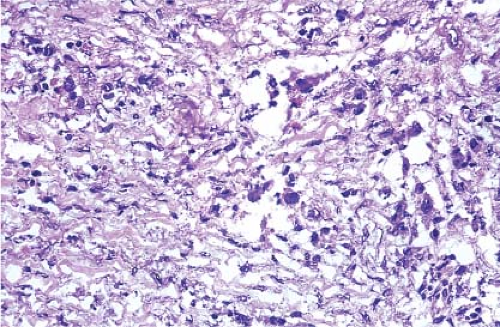

frozen section requires no special skill or secret maneuver other than attention to traditional morphologic detail: recognition of the standard alterations in growth pattern, under low-power observation, just as would be appreciated on routine paraffin-embedded sections (Fig. 8.2). Employing imprint preparations along with the actual frozen section facilitates the appreciation of cytologic detail (Fig. 8.3, e-Figs. 8.2–8.4). The ability to discriminate infiltrating cancer from a radial scar lesion, inflammatory

infiltrates, fat necrosis, sclerosing adenosis, and involutional changes in a papilloma relies on adequate sampling and basic morphology. It is not good practice, not to mention potentially dangerous, for the pathologist to ignore these fundamental morphologic and technical principles.

frozen section requires no special skill or secret maneuver other than attention to traditional morphologic detail: recognition of the standard alterations in growth pattern, under low-power observation, just as would be appreciated on routine paraffin-embedded sections (Fig. 8.2). Employing imprint preparations along with the actual frozen section facilitates the appreciation of cytologic detail (Fig. 8.3, e-Figs. 8.2–8.4). The ability to discriminate infiltrating cancer from a radial scar lesion, inflammatory

infiltrates, fat necrosis, sclerosing adenosis, and involutional changes in a papilloma relies on adequate sampling and basic morphology. It is not good practice, not to mention potentially dangerous, for the pathologist to ignore these fundamental morphologic and technical principles.

Figure 8.2 Infiltrating ductal carcinoma. Dense fibrous tissue investing poorly oriented cords of large, pleomorphic malignant cells. No normal breast tissue is present. |

In part because of early diagnosis and effective treatment, breast cancer has now become a chronic disease. Occasionally, after definitive therapy, an unsuspected metastasis or recurrence may be encountered during a breast reconstruction procedure (Fig. 8.4A,B). Patients may present years after their primary diagnosis with metastatic lesions. The diagnostic context depends heavily on the history and a consideration of breast cancer by the pathologist (Figs. 8.5–8.8). The most important point to remember is that if the frozen section is not absolutely diagnostic of cancer, defer the diagnosis (Figs. 8.9 and 8.10, e-Figs. 8.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree