Fig. 24.1 The forehead of the animal was divided into two symmetric halves. The left side was injected with botulinum neurotoxin , the other with saline. Subsequently, standardized excisions were performed and closed in a standardized fashion by a blinded facial plastic surgeon. Immobilization of the experimental wounds was observed 1 week after the treatment, while the wounds on the experimental side continued to be distorted by the activity of the underlying frontalis muscle (top frames).

Human use of chemo-immobilization

Initial case reports of human use included traumatic wounds of the forehead and subsequently of the perioral region. They were followed by use for surgical wounds of the rest of the face and of the neck. No adverse effects or complications were reported. Of note, many patients opted for aggressive immobilization even of functionally important areas such as the lip, in the hopes of maximizing the therapeutic effect. For example, temporary paralysis of the lip was discussed as an example of the treatment effect and not of being an untoward effect or a complication. With further positive experiences, the indications were broadened and included pediatric applications.

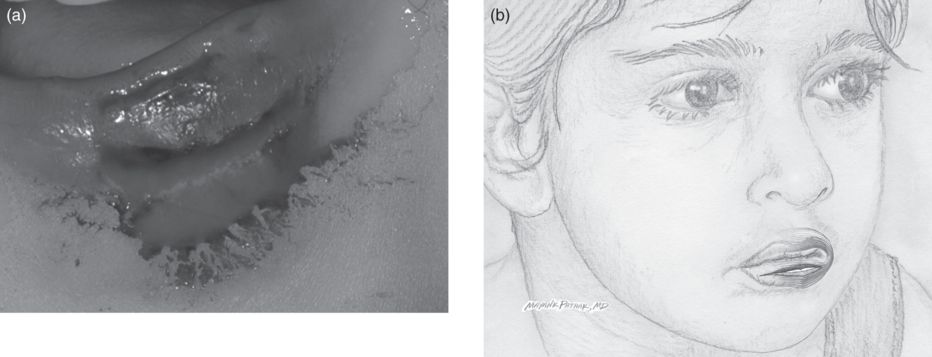

Figure 24.2 shows a lower lip wound in a 1-year-old infant. The lower wound is a complete through-and-through defect; the upper wound is about a 50% depth defect. Figure 24.3 shows anatomical closure of the wound in a layered fashion. After appropriate informed consent of the off-label use of the therapy and also of the somewhat limited experience in infants, the wound was aggressively immobilized by intramuscular injection of BoNT. The infant was observed to have decreased mobility of the lower lip for about 8 to 10 weeks after the treatment. Food intake and articulation was not compromised. Figure 24.4 shows the intramuscular treatment of the wound with BoNT during surgery. The wound healed uneventfully and the cosmetic result seemed very favorable. Figure 24.5 shows the wound with 5 years of follow-up.

Fig. 24.2 Through-and-through defect of the lower lip in a 1-year old infant.

Fig. 24.3 Anatomical repair is performed in a layered fashion utilizing resorbable suture material.

Fig. 24.4 The underlying orbicularis oris muscle is injected with botulinum neurotoxin A.

Fig. 24.5 Five-year follow-up photograph of the resulting scar.

Clinical trial

The first clinical trial of chemo-immobilization was performed at the Mayo Clinic (Gassner and Sherris, 2000). Surgical and traumatic wounds of the forehead were included in the study. According to a randomized protocol, patients were injected with normal saline or with BoNT. Dosages of 15 U/2 cm wound length were applied. This dosage is large compared with the cosmetic use of BoNT; it has been the author’s long-term observation that chemo-immobilization for healing wounds requires a higher dosage and more aggressive treatment than the immobilization used for forehead wrinkles. This may be because a relatively broad area around the scar requires treatment for adequate immobilization of the wound edges. After completion of the study, close-up photographs taken at the 6-month follow-up were presented to a blinded panel of evaluators, who then graded the cosmetic appearance of the resulting wound taking into account the original wound and trauma. The experimentally immobilized wounds were rated as cosmetically more favorable compared with the control wounds, which led to the conclusion that aggressive immobilization of wounds located on the forehead has a favorable effect on the eventual scarring.

Gassner and Sherris (2000) noted that the effect of BoNT on immobilization varied greatly depending on the anatomical area. Figures 24.6 to 24.9 illustrate this observation. This 21-year-old woman sustained soft tissue cuts to the forehead and the cheek. Both wounds were deep; the forehead wound reached the periosteum and was more complex than the somewhat shallower cut on the cheek. Both wounds were meticulously closed in a layered fashion and subsequently aggressively immobilized with a total dose of 60 U BoNT serotype A (Fig. 24.6). At 6 months, both scars were in the maturation phase. The cheek scar showed more pronounced erythema and widening compared with the forehead scar (Figs. 24.7–24.9). The forehead and the perioral area seem to be particularly well suited for BoNT-induced immobilization, the suitability of the cheek and neck appearing more limited. Consequently, caution should be employed in extrapolating from these results to other parts of the body.

Fig. 24.6 Immobilized soft tissue wounds of the forehead and cheek in a 21-year-old female. The frontalis, zygomaticus and buccinator muscles were injected with a total dosage of 60 U botulinum neurotoxin A.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree