Fig. 20.1 Extraocular muscle injection.

This book illustrates that strabismus has been joined by a wide range of disorders for which BoNT has emerged as an important or even first-line treatment, in addition to cosmetic indications. Around the eye/orbit, a number of diseases can be treated with BoNT: predominantly essential blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm (Chapters 8 and 13; for both BoNT is the first choice treatment) but also to lengthen retracted lids and to overcome double vision in Graves’ disease, to reduce oscillopsia and improve vision in nystagmus, to produce protective ptosis in lagophthalmos or corneal diseases, to reduce tearing through injections into the lacrimal gland, and to treat special cases of spastic entropion.

Treatment of strabismus with botulinum neurotoxin

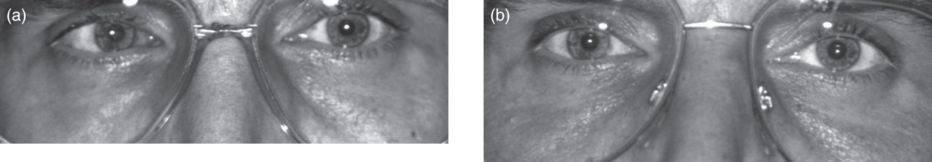

Physical realignment of the eyes is often needed in strabismus treatment to remove diplopia and to align the eyes to allow development of binocular function, and also for cosmesis. Use of BoNT was developed as an alternative to surgery to treat small angles (Fig. 20.2), to treat infantile esotropia, to reduce antagonist contracture in acquired paralytic strabismus and for patients who decline surgery. In the eye muscle system, an interval of 3–4 months of reduced abnormal activity is not the goal as it is in blepharospasm and many other disorders. Instead, the induced paralysis acts to alter eye position and hence alters eye muscle lengths for a period of 2–3 months. The muscles respond to this change by sarcomeric adaptation, actual lengthening of the injected muscle and shortening of the antagonist, just as do skeletal muscles (Scott, 1994). In general, about 40% of patients are corrected to within 10 prism diopters at 1 year with one injection and about 65% corrected with an average of 1.6 injections.

Fig. 20.2 Small angle esotropia. (a) Before treatment; (b) 3 months after botulinum neurotoxin injection of the medial rectus muscle.

Indications

Injections of BoNT in extraocular muscles are useful for both normal and restrictive strabismus.

Sixth nerve paralysis is a frequent indication: the medial rectus is injected to reduce contracture. There is often a good effect on double vision. In patients who have a good prognosis (e.g. a diabetic or hypertensive origin of the paresis), BoNT can provide earlier rehabilitation. In patients with more severe paresis where a long recovery time is anticipated, the contracture of the medial rectus and the increase of esotropia can be prevented. Functional as well as cosmetic results are available compared with those who do not receive BoNT injections. An operation such as a transposition procedure is necessary in patients with permanent paralysis, but BoNT can improve contracture of the medial rectus and thereby avoid surgical recession and its concomitant reduction of range of motion. In addition, the anterior ciliary artery supply is left intact, reducing or eliminating the problem of anterior segment ischemia.

Certain patients with third and fourth nerve paresis are also helped by BoNT injection (Mc Neer et al., 1999).

A number of strabismus specialists are treating children with infantile esotropia, acquired esotropia, intermittent exotropia and strabismus in cerebral palsy. Results approach those of surgery and the need for only brief general anesthesia is an added advantage.

In adult strabismus, BoNT injection is particularly valuable in patients who have had frequent surgery and who fear further operation without adequate long-term success. There are often rewarding results for strabismus after retinal detachment or cataract, particularly with smaller strabismic angle and normal binocular vision. Injection of BoNT is also useful as a postoperative adjustment for those patients with squint when the intended goal of surgery has not been achieved or for whom further surgical procedure may threaten the vascularity of the anterior segment. Diplopia from strabismus in chronic myasthenia and in progressive external ophthalmoplegia is an additional indication. For a discussion of the place of BoNT in these specific strabismus cases, see McNeer et al. (1999).

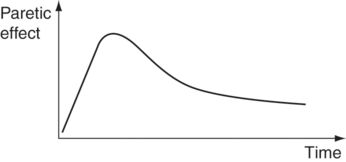

In addition to the well-documented indications mentioned above, the authors use BoNT injection in adults who desire strabismus correction but who respond with diplopia to preoperative prism adaptation or forced duction tests. The eye position to be achieved by an operation can be temporarily tested with respect to double vision during the period of overcorrection, around 1 week after BoNT injection (Fig. 20.3). It has been shown that there is adaptation of suppression or habitation to double vision in 80% of patients (Nuessgens and Roggenkamper, 1993).

Fig. 20.3 Paretic effect of extraocular muscle injection over time. The maximum effect occurs 10–14 days after injection.

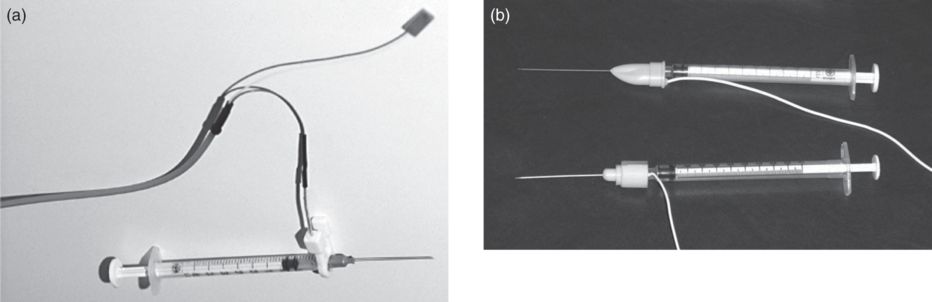

Electromyography guidance for injection

Teflon-insulated injection needles that record only from the tip localize the site of injection in active muscle. These and an electromyography (EMG) amplifier are important tools for use in eye muscle injection. Practiced injectors do well without EMG for previously unoperated medial rectus, but EMG guidance is very helpful for vertical muscles, for unusual muscle involvement (e.g. in Graves’ disease) and for those who have had previous surgery. The sharp sound of individual motor units indicates correct penetration of the muscle; this is easily appreciated and differentiated from the general hum of nearby muscle. Injection under direct vision after a small conjunctival opening is also good practice. Occasionally, EMG is of use to locate muscles that have been displaced and to determine if a weak muscle is partly or wholly denervated (Figs. 20.4–20.6).

Fig. 20.4 Electromyography. (a) Bipolar wire for recording. One pole is connected to the special injection needle. (b) There are also fixed connections between the electric wire and needle that are commercially available.

Fig. 20.5 Before injection, functioning of the equipment is tested by recording the electric activity of the orbicularis muscle.

Fig. 20.6 Injection of the right lateral rectus muscle.

Dosage

For comitant strabismus of 15–30 prism diopters, the initial dose is 2.5 U onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox); for larger deviations 5.0 U onabotulinumtoxinA is used. (Other BoNT formulations could also be used, but we have less experience with them; all subsequent dosing in this chapter will also refer to onabotulinumtoxinA.) Based on the experience with other indications, a 1:1:3 relationship for onabotulinumtoxinA:incobotulinumtoxinA:abobotulinumtoxinA could be estimated but physicians should base the dose to use on personal experience. While most muscles respond well to this dosage scheme, occasionally individuals will require much more BoNT for treatment to be effective. We increase the dose by about 50% if an initial dose was inadequate as measured by the degree of induced paralysis and the resulting correction. For medial rectus injection in partial lateral rectus paresis, a dose of 1.0–1.5 U is appropriate.

The intended volume with some extra should be loaded into a 1.0 ml tuberculin syringe; the electrode needle is firmly attached and the excess fluid is ejected to assure patency of the needle and absence of leak at the needle/hub. For multiple muscles, multiple syringes are good, as it is often impossible to view the gradations on the syringe for partial volume injection. The EMG amplitude diminishes as the bolus of fluid pushes the muscle fibers away from the injection site, a sign of a good insertion. The needle is left in place 30–60 seconds after injection to allow the injection bolus to dissipate in the muscle – otherwise it can run back out the needle tract, as shown with dyed solution in animals.

Anesthesia

Proparacaine 1% drops are followed 30 seconds later by an alpha-agonist such as brimonidine tartrate ophthalmic solution (Alphagan) or epinephrine 0.1%. Three additional proparacaine drops are placed at intervals of 1 minute. Where there is scar tissue from prior muscle surgery, injection of 100–200 μl lidocaine 2% beneath the conjunctiva is helpful.

Targeted muscles

Medial rectus

The patient gazes at a target slightly into abduction with the fellow eye. The electrode tip is inserted 8–10 mm from the limbus, avoiding blood vessels, and advanced straight back to a position behind the equator of the eye. Gaze is then slowly brought to moderate adduction to activate the muscle. The needle and syringe is rotated to keep the electrode tip in position relative to the muscle. Some muscle activity is usually heard at this point, but the needle should be advanced until a sharp motor unit sound is produced. Botulinum neurotoxin diffuses about 15 mm from the point of injection and so does not need to be placed far back in the muscle.

Lateral rectus

This is treated similarly to medial rectus, recognizing that the needle must be first directed backward behind the equator of the eye, then angled medially 40 degrees or so.

Inferior rectus

This is injected very much as for horizontal muscles. Keeping on the orbital side of the muscle to avoid penetrating the globe, the needle will often penetrate the inferior oblique. The path should be continued on through the inferior oblique, slanting medially about 23 degrees along the line of the inferior rectus. There is a step up in the orbital floor 15 mm from the orbital apex and the electrode will often hit against that – angling superiorly will put it directly in the inferior rectus. Injection through the lower lid is easier in thyroid eye disease. The electrode is inserted at the midpoint of the lid, about 8 mm from the lid margin. Penetration through the inferior oblique is usual.

Inferior oblique

The inferior oblique is injected through the conjunctiva, aiming for a point slightly temporal to the lateral border of the inferior rectus at about the equator of the eye. With the eye in far up-gaze, the inferior oblique is highly innervated and its insertion is moved forward, making the muscle accessible.

Superior rectus and superior oblique

These are seldom injected as prolonged and severe ptosis always results from diffusion of BoNT from the target muscle.

Complications and adverse outcomes

Overflow from diffusion of BoNT causes transient vertical deviation and ptosis, particularly after medial rectus injection in 5–10% of patients; in 1–2% these persist over 6 months. Undercorrection is the most frequent adverse outcome. If an earlier injection was not fully paralytic, reinjection at a higher dose can be considered. Progressive correction of large deviations is possible by multiple injections.

Bupivacaine and botulinum neurotoxin

The ability of bupivacaine to enlarge and strengthen eye muscles, used either alone or in conjunction with BoNT, with effects lasting years rather than a few months characteristic of BoNT treatment alone, has further enlarged the role of injection as a valuable treatment approach for strabismus (Scott et al., 2009)

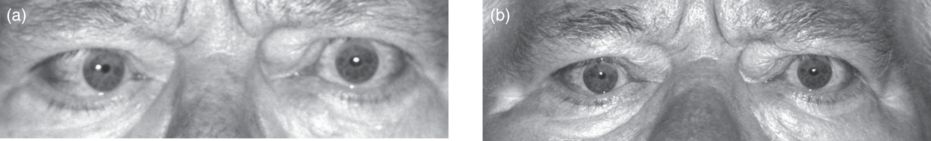

Endocrine disorders: endocrine myopathy

Although only 15% of the authors’ patients achieved a permanent result, BoNT injection into the involved (thickened) eye muscles is very useful to diminish double vision and anomalous head position in patients where the angle of squint is yet not stable. After injection, the passive motility restriction becomes better and patients feel less tension around the eye. This disease is suitable for the beginner in eye muscle injection techniques because the eye muscles are thickened and easier to hit. In a number of patients, it has not been possible to get appropriate EMG signals, but even without these the injections were effective. Injection of the inferior rectus can also easily be performed transcutaneously, as mentioned above (Figs. 20.7 and 20.8).

Fig. 20.7 Endocrine myopathy of the right medial rectus muscle. (a) Before treatment; (b) 3 weeks after botulinum neurotoxin injection into the affected muscle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree