Chapter Thirty-One. Bleeding in pregnancy

CHAPTER CONTENTS

Bleeding in early pregnancy

Bleeding from the genital tract during pregnancy is abnormal and a doctor should see all women who report bleeding, irrespective of the amount. Bleeding prior to the 24th week of pregnancy may be caused by implantation bleeding, abortion, ectopic pregnancy, trophoblastic disease and lesions of the cervix or vagina. Research by Weiss et al (2004) compared 16 506 women, some of whom did not bleed and others who had light or heavy bleeding. Women with light bleeding were more likely to develop pre-eclampsia, have a preterm birth or placental abruption. The women with heavy bleeding were more likely to lose their pregnancy before 24 weeks. The conclusions were that the severity of bleeding was a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcome.

Implantation bleeding

Normal implantation is thought to occur in three stages (Potdar & Konje 2005):

• Apposition: the blastocyst sits adjacent to the endometrium—an unstable situation.

• Stable adhesion: increased activation of the syncytiotrophoblast with the endometrium.

• Invasion.

As the syncytiotrophoblast cells erode the maternal endometrium during embedding, a small amount of bleeding may occur at about 6–7 days (Norwitz et al 2001). By 10 days the blastocyst is completely covered by the decidua; this is just before the next menstrual period is due. Women may think this is a normal but short menstruation. Implantation is a complex interaction between the blastocyst and the endometrium and ‘various adhesion molecules’ (Potdar & Konje 2005). At this early stage women often do not know they are pregnant. If the blastocyst does not implant, then menstruation begins, although a little late, and the conceptus is lost with menstrual debris.

Abortion

Spontaneous abortion is the complete loss of the products of conception prior to the 24th week of pregnancy; 10–15% of diagnosed pregnancies are lost before 20 weeks (Potgar & Konje 2005). However, most of them are lost before implantation and only a quarter of them are clinically recognized as abortions. The aetiology of abortion is shown in Table 31.1.

| Cause | Percentage of total |

|---|---|

| Genetic abnormalities: mainly chromosomal abnormalities arising during meiosis of ovum or sperm | 50–60 |

| Endocrine abnormalities: progesterone deficiency, thyroid deficiency, diabetes, increased androgens, elevated luteinising hormone as in polycystic ovary | 10–15 |

| Chorioamniotic separations: there may be bleeding beneath the chorion or between the amnion and chorion | 5–10 |

| Incompetent cervix: usually the result of cervical trauma | 8–15 |

| Infections: usually ascending, but occasionally due to systemic microbial infections such as rubella, listeria, toxoplasmosis, chlamydia | 3–5 |

| Abnormal placentation: failure of the trophoblastic invasion of the spiral arteries, linked to raised blood pressure | 5–15 |

| Immunological abnormalities: may be the cause of repeated spontaneous abortions and have recognisable serum antibodies | 3–5 |

| Uterine anatomic abnormalities: caused mainly by failure of the Müllerian ducts to unite in the embryonic stage resulting in septate uterus; a fibroid uterus may also cause abortion | 1–3 |

| Unknown reasons | <5 |

About 80% of all abortions will occur before 12 weeks gestation; the rest will occur between 13 and 24 weeks and are referred to as late abortions. The majority of early abortions are due to anembryonic pregnancies or blighted ova suggestive of genetic faults, while those with a formed fetus suggest the possibility of many causes and occur after 13 weeks. Fifty per cent of conceptions are lost before the next menstruation, 30% soon after the missed cycle and 65–90% of these losses are recognised as chromosomally abnormal (Lockwood 2000). This may be linked to older women and pregnancy loss. The incidence of loss is higher in IVF pregnancies probably due to the underlying causes of infertility in the first place (Mukhopadhaya & Arulkumaran 2007).

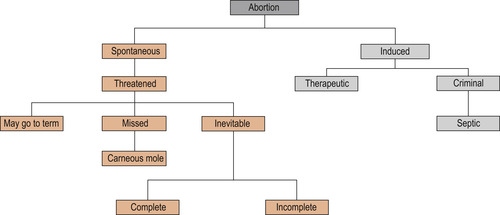

Classification of abortion (Fig. 31.1)

Threatened abortion

In threatened abortion, painful or painless bleeding occurs, the cervical os is closed and ultrasound will define a live fetus when conservative treatment such as bed rest is advised. The outcome may be resolution and continuance of the pregnancy or proceed to an inevitable abortion.

|

| Figure 31.1 The classification of abortion. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Inevitable abortion

A diagnosis of inevitable abortion is made on the fact that the cervical canal is open; ultrasound will define if the fetus is alive. Blood loss may be heavy and cause maternal collapse with increasing abdominal pain. The uterus may spontaneously evacuate its contents or surgical or medical removal with mifepristone (RU4B6) may be necessary to remove retained products. Expectant management is sometimes an alternative to operative measures for removing retained products of conception. Ultrasound measures endometrial thickness and the presence of a gestational sac. If left to nature, most women will lose the retained products naturally. This management requires regular follow-up as an outpatient and access to the clinic by phone (Cahill 2001, Luise et al 2002).

Missed abortion

This is now termed early fetal demise (Cahill 2001). A blood-stained or brown loss may be evident, the woman may or may not still feel pregnant and the signs of pregnancy may disappear. Low levels of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) may be found, in which case the conceptus has died or ultrasound confirms fetal death. A suction curette or oral mifepristone may be used. If the uterus is larger than 13 weeks, a combination of vaginal prostaglandins and intravenous Syntocinon (oxytocin) may be prescribed. Although the uterus would eventually expel the mole, there is a risk of disseminated intravascular coagulation because of the toxins produced by a dead fetus.

Recurrent miscarriage (abortion)

Recurrent abortion is the term used for three or more consecutive abortions. Only 0.4% of women suffer in this way but they have a 55% increased risk of having a fourth miscarriage (Eblen et al 2000). In some women the cause is unknown but there is a specific group of women who suffer from antiphospholipid antibodies (Hughes syndrome), some 10–16% who will continually abort. In other words, the mother produces antibodies against the fetus. These antibodies also affect clotting factors and the process of abortion is thought to involve the activation of clotting mechanisms on the endothelial decidual cell surface (Singh 2001).

Induced abortion (therapeutic)

Therapeutic abortions have been available in the UK since 1967 but there are other countries where the procedure is illegal. The lack of an abortion law leads to the risk of women seeking illegal abortions, often carried out in unfavourable conditions by unskilled practitioners. In the past this often resulted in a septic abortion, which occurred because of infection, and the woman suffered from septicaemia, endotoxic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Infection leads to the development of adhesions, and infertility. Fatalities were common. As for long-term health problems, there seems to be no connection between induced abortion and later early pregnancy loss or the incidence of ectopic pregnancy, but the risk of preterm birth and placenta praevia in subsequent pregnancies is increased (Thorp et al 2003).

It should be considered that, if a woman is pregnant and the pregnancy is unwanted, then she may choose the route to abort the baby. Other women abort because of fetal abnormality and this in itself is difficult for the woman and her partner. Some women are treated as outpatients using mifepristone or prostaglandins followed by a suction evacuation under a general anaesthetic if deemed necessary.

Gestational trophoblastic tumours

Chorionic tumours deriving from the placenta include hydatidiform mole (partial or complete), placental site tumours and choriocarcinoma with varying degrees of the diseased tissue spreading and causing malignancy. Placental site tumours are rare and generally treated with hysterectomy followed by chemotherapy (Hassadia et al 2005, Trommel et al 2005).

Hydatidiform mole

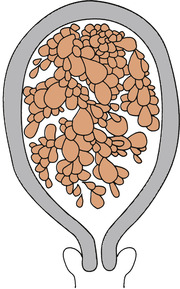

Hydatidiform mole is a benign neoplastic disease, an abnormal growth of the trophoblast where the chorionic villi proliferate, become avascular and are filled with fluid. The mole looks like a bunch of grapes, often filling the uterus, which clinically palpates large for dates (Fig. 31.2). Complete and partial moles have abnormal sets of chromosomes (Fig. 31.3); a complete mole will have a 46XX where all chromosomes are of paternal origin. The ovum has no nucleus but has been fertilised by one spermatozoon. A partial mole where a fetus may be present is usually triploid, either 69XXX or 69XXY where two spermatozoa have fertilized one ovum (Blackburn 2007, Trommel 2005).

|

| Figure 31.2 A hydatidiform mole. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

|

| Figure 31.3 Genetic origins of complete and partial hydatidiform moles. |

Aetiology

There are wide variations in incidence: 2:1000 in Japan; 1:1000 in Europe and North America; and 1:1945 in Ireland. It is suggested that diet and socioeconomic factors may play a role, particularly the lack of carotene and animal fats (Berkowitz & Goldstein 1996). Women over 35, and who have had a previous mole, have an increased risk of a complete mole.

Signs and symptoms

• Intermittent vaginal bleeding with increasing bleeding as the mole is aborted.

• Early onset of pre-eclampsia.

• The uterus is large for dates and no fetal parts will be palpated in a complete mole.

• There may be mild signs of thyrotoxicosis and hyperemesis gravidarum due to the action of hCG, which is similar to thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) (Misra et al 2002).

• Diagnosis is confirmed by ultrasound scan, which will show a snowstorm effect of multiple vesicles.

• Urinary or serum hCG is very high, exceeding that of a multiple pregnancy.

Management

Complete emptying of the uterus by suction and then curettage to eliminate all diseased tissue is essential. The molar tissue always expresses the RhD factor; therefore Rh-negative women require rhesus immunoglobulin following evacuation (Berkowitz & Goldstein 1996). Follow-up at one of the three centres in the UK for the measurement of hCG until hCG levels are normal (urine hCG 0–24 IU/L; serum hCG 0–4 IU/L) will be routine. Follow-up will continue for life with an incidence of recurrence of a molar pregnancy being 1:75 (http://www.Hmole-chorio.org.uk, accessed June 2008). Hormonal contraception should be avoided, as it increases the chance of developing malignant disease.

Choriocarcinoma and placental site tumours

The diagnosis of a choriocarcinoma is the presence of a persistently raised level of hCG (>2000 IU/L). A tumour consisting of placental tissue and haemorrhage debris and the spread to lung and brains is typical. Other symptoms such as haemorrhage and rising levels of hCG are also diagnostic. The tumour is very invasive and treatment must be commenced immediately following diagnosis. Placental site tumours can be difficult to diagnose, with hCG levels less elevated but not markedly as in choriocarcinoma; irregular bleeding may be a first sign.

Treatment

Choriocarcinoma in all its presentations responds very well to chemotherapy. To assist in the treatment process a scoring system is used: women scoring 0–8 are low risk and are administered methotrexate and folinic acid; those scoring above 8 receive etoposide, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide and vincristine (McNeish et al 2002). The problem of toxicity is as for every use of cytotoxic drugs with malaise, stomatitis, pharyngitis, diarrhoea, leucopenia and alopecia occurring. Follow-up treatment will continue for life with some women opting for hysterectomy.

Ectopic pregnancy

An ectopic pregnancy occurs when the fertilised ovum implants outside the uterine cavity, commonly diagnosed between 6 and 10 weeks (Murray et al 2005). In 95% of cases the site of implantation is the uterine tube. More rarely, the implantation site may be the ovary, the cervical canal or the abdominal cavity. Ectopic pregnancy is a serious condition and is a major cause of maternal death. Reasons for death have been stated as, in the main, missed diagnosis in primary care and accident and emergency. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG 2002) recommend the use of the urinary hCG dipstick test to ascertain pregnancy to prevent missed diagnosis. The use of vaginal ultrasound also aids diagnosis and may prevent the drastic operative measures of salpingectomy (Farquhar 2003, Levine 2007).

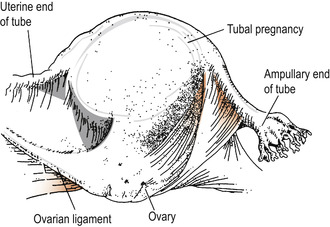

Tubal pregnancy

There is a rise in the incidence of tubal pregnancies due to the increase in sexually transmitted diseases, in particular by Chlamydia trachomatis (Tay et al 2000). Any condition that delays the transport of the zygote along the uterine tube may lead to a tubal pregnancy (Fig. 31.4). This may be due to malformation of the tubes but is more likely due to tubal scarring and the loss of cilia due to pelvic infection.

|

| Figure 31.4 Tubal pregnancy. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Risk factors

Risk factors for tubal pregnancy include (Tay et al 2000):

• An older woman.

• Women of low gravidity or parity.

• Previous tubal pregnancy.

• Tubal surgery.

• Salpingitis.

• Intrauterine contraceptive device.

• Hormonal stimulation of ovulation.

• In vitro fertilisation and embryo transplant.

• Tubal endometriosis.

• Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

• Pelvic or abdominal surgery.

• Progestogen-only pill (interferes with the action of the cilia).

Pathophysiology

Implantation may occur in various sites along the genital tract (Table 31.2).

| Position | Percentage occurrence |

|---|---|

| The fimbriated part of the tube | 17 |

| The ampulla | 55 |

| The isthmus | 25 |

| The ovary | 0.5 |

| The abdominal cavity | 0.1 |

The outcome varies depending on where in the tube implantation occurs, the ability of the tube to distend and the size of blood vessels eroded. If the pregnancy occurs in the fimbriated end or the ampulla, the conceptus may continue to grow until 10 weeks. The gestation sac may be expelled into the abdominal cavity as a tubal abortion (Fig. 31.5). Blood clot may be organised around the separated sac to form a tubal mole, which may remain in the uterine tube or be expelled from the fimbriated end as a tubal abortion. Tubal rupture (Fig. 31.6) may lead to devastating haemorrhage. The most severe haemorrhage occurs if the zygote implants at the level of the isthmus where the mucosa is thinner and the blood vessels larger. Tubal rupture is likely to occur between the 5th and 7th weeks of pregnancy.

|

| Figure 31.5 Tubal abortion. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

|

| Figure 31.6 Rupture of the uterine tube. (From Henderson C, Macdonald S 2004, with kind permission of Elsevier.) |

Diagnosis

The condition may be subacute or acute with signs of shock and collapse. The condition is serious and should always be suspected in women of childbearing age, especially if there is a history of amenorrhoea or previous salpingitis. The likely signs and presenting history of ectopic pregnancy are given in Table 31.3 (Tay et al 2000).

| Sign | Percentage occurrence |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 97 |

| Abdominal tenderness | 91 |

| Vaginal bleeding | 79 |

| Adnexal tenderness | 54 |

| History of infertility | 15 |

| Use of intrauterine device | 14 |

| Previous ectopic pregnancy | 11 |

Delay in diagnosis may be fatal as the clinical picture is similar to PID or threatened abortion:

• The woman will give a history of early pregnancy signs.

• The uterus will have enlarged but feel soft.

• Abdominal pain may occur as the tube distends and uterine bleeding may be present as the endometrium begins to degenerate.

• The abdomen is tender and may be distended.

• Shoulder tip pain may be due to referred pain.

• The woman may appear pale, complain of nausea and collapse.

• Severe pain may be felt during pelvic examination, especially if the cervix is moved.

• A mass may be felt in the adnexi on one or other side of the uterus.

• Hormonal assay will find progesterone levels to be low and hCG levels may be low or falling (Farquhar 2003).

• Ultrasound scanning may show fluid in the pelvic cavity, a mass in the pelvic cavity and absence of an intrauterine pregnancy (Levine 2007).