Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

Explain the basic principles of pharmacy billing and reimbursement.

Explain the basic principles of pharmacy billing and reimbursement.

Define common pricing benchmarks.

Define common pricing benchmarks.

List various payers of pharm Describe the differences in reimbursement processes dependent on aceuticals and pharmacy services.

List various payers of pharm Describe the differences in reimbursement processes dependent on aceuticals and pharmacy services.

payers and patient care settings.

payers and patient care settings.

Describe the categories of information that are needed to submit a thirdparty claim for a prescription or medication order.

Describe the categories of information that are needed to submit a thirdparty claim for a prescription or medication order.

Use knowledge of third-party insurance billing procedures to identify a reason for a rejected claim.

Use knowledge of third-party insurance billing procedures to identify a reason for a rejected claim.

Key Terms

| adjudication | Prescription claims adjudication refers to the determination of the insurer’s payment after the member’s insurance benefits are applied to a medical claim. |

| average manufacturer price (AMP) | The average price paid to manufacturers by wholesalers for drugs distributed through retail pharmacies. This includes discounts and other price concessions that are provided by manufacturers. |

| average sales price (ASP) | Price based on manufacturer-reported selling price data and includes volume discounts and price concessions that are offered to all classes of trade. |

| average wholesale price (AWP) | A commonly used benchmark for billing drugs that are reimbursed in the community pharmacy setting. The AWP for a drug is set by the manufacturer of the drug. |

| coinsurance | A percentage charge for a service, such as a prescription or doctor visit. |

| copayment | An amount that insured individuals must pay for a service, such as a prescription or doctor visit, each time they use the insurance benefit. |

| cost sharing | The amount of insurance costs shared by the employee or beneficiary. |

| coverage gap | Also referred to as the “donut hole.” This is a period of no coverage that typically occurs once the individual’s total prescription drug spending for the year reaches the initial coverage limit. During the coverage gap, the beneficiary must pay all costs for prescriptions until the total prescription spending for the year reaches the catastrophic coverage threshold. |

Payment for Drugs and Dispensing Services

Billing for Drugs and Dispensing Services

|

In addition to providing goods and services, all businesses share a common goal—to make a profit. Even nonprofit organizations need to generate enough revenue to cover their expenses in order to remain viable. Pharmacies are no exception. In many practice settings, pharmacy technicians serve as the patient’s first point of contact with the pharmacy billing system, so it is important for them to understand the basic concepts related to billing and reimbursement. This chapter provides a broad overview of the principles of pharmacy billing and reimbursement.

Pharmacy Accounting Basics

Most pharmacies are “hybrid businesses”; that is, they provide both goods and services. Although pharmacists provide many services that help ensure that patients use medications appropriately, the primary source of revenue generation for a pharmacy is the sale of products (i.e., drugs). In simple accounting terms, revenue represents the inflow of funds. Money is exchanged for goods and services that are provided. In a typical pharmacy setting, prescription and nonprescription drug sales account for the highest portion of revenue.

The outflow of cash is considered expenses. Before the revenue can be generated, the products (i.e., drugs) must be purchased by the pharmacy. The amount the pharmacy pays to a vendor to buy the drugs for stock is called the acquisition cost. In pharmacy terms, the margin is typically the difference between the selling price of a drug to the patient and the acquisition cost of the drug.

Margin = Amount paid by the patient – acquisition cost of drugs

Example: For a drug with an acquisition cost of $20 and for which the patient paid $50

Margin = $50 – $20 = $30

In addition to drug purchases, there are overhead costs associated with providing pharmaceutical products to patients. Overhead costs often include various expenses such as rent and utilities, personnel costs (i.e., salaries for pharmacists and technicians), equipment (computers, fax, printer), and supplies (labels, vials, etc.). These expenses represent cash outflow. The net profit is the amount of money that is left over after all of the expenses have been paid.

Net Profit = Total revenue – total expenses (i.e., cost of drugs and other expenses)

Example: for a business with total revenue of $10 million and total expenses of $9 million

Net Profit = $10 million – $9 million = $1 million

In order for a pharmacy or any business to make a profit, the total revenue must exceed total expenses. Within the past five years, there have been significant changes in reimbursement for drugs, which affects pharmacy profits. Pharmacy technicians who have knowledge of basic drug reimbursement principles can play a significant role in increasing pharmacy profit margins.

Pharmacy Reimbursement Basics

Reimbursement for pharmaceuticals is complex and widely variable. Fortunately, most pharmacy computer systems have reimbursement rates and formulas programmed into the software application. However, it is important for pharmacy technicians to understand how pharmacies are reimbursed for drugs. The exact methodology that is used to bill and reimburse for drugs varies based on several factors, including the following:

The practice setting in which the drug is dispensed.

The practice setting in which the drug is dispensed.

The type of drug that is being dispensed (e.g., single-source brand products vs. multisource generic products).

The type of drug that is being dispensed (e.g., single-source brand products vs. multisource generic products).

The party who is paying for the drugs.

The party who is paying for the drugs.

For example, in institutional settings such as hospitals and hospital-based outpatient clinics, payment for drugs may be prospective, which means that the amount to be paid for drugs is predetermined based on the condition that is being treated. Prospective payment typically includes all costs associated with treating a particular condition, including medications. With prospective payment systems, pharmacies are challenged to deliver drugs at or below the predetermined rate in order to ensure that drug costs are covered. More information on prospective payment methods is presented later in this chapter.

In community pharmacy practice, the most common type of payment method is retrospective, or fee for service. In the retrospective payment model, drugs are dispensed, and later reimbursed, according to a predetermined formula that is specified in a contract between the pharmacy and the third-party payer, such as the insurance company or pharmacy benefit manager. The reimbursement rate for third-party prescriptions is based on a formula consisting of various parts: ingredient cost, dispensing fee, and patient copayments. The ingredient cost is the amount paid to the pharmacy for the cost of the drug product, the dispensing fee is the amount paid for dispensing the prescription, and the copayment (also known as “copay”) is the cost-sharing amount paid by the patient or customer. In order for the pharmacy to make a profit, the total reimbursement rate should be greater than the costs to dispense the prescription.

Third-party reimbursement = (ingredient cost + dispensing fee) – copayment

The ingredient cost is based on a payment benchmark, or a standard against which pricing is based. Benchmark prices are often referenced by common acronyms, as described in the following text.1

Historically, the average wholesale price (AWP) has been the most commonly used benchmark for billing drugs that are reimbursed in the community pharmacy setting. AWP was created in the 1960s and was the first generally accepted standard pricing benchmark. The AWP for a drug is set by the manufacturer of the drug, and the AWP is readily available from several sources, including MediSpan and First Databank. AWP is known as the “sticker price” of a drug that the pharmacy sells to a customer or third-party payer. AWP is usually set at 20–25% above the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), another common benchmark for billing for drugs.2

Wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) is set by each manufacturer. It represents the “list price” at which the manufacturer sells the drug to the wholesaler. However, WAC does not include any discounts or price concessions (e.g., reduced prices for on-time payment) that may be offered to the drug wholesaler. If AWP is the basis for reimbursement, the formula is usually the AWP less some percentage (e.g., AWP – 15%). If WAC is the basis, the formula is usually WAC plus a small percentage (e.g., WAC + 3%).2

There is growing recognition that neither AWP nor WAC represents what is actually paid for drugs, and, in recent years, these benchmarks have become widely controversial.1–2 New benchmarks that are used for drug pricing within the past decade include average sales price (ASP) and average manufacturer price (AMP). ASP is based on manufacturer-reported selling price data and includes volume discounts and price concessions that are offered to all classes of trade. ASP is explained in further detail in the Medicare section of this chapter. Other third-party payers will likely begin to use ASP as the benchmark for drug pricing in the future.1

AMP is the average price paid to manufacturers by wholesalers for drugs distributed through retail pharmacies. AMP includes discounts and other price concessions that are provided by manufacturers. AMP was created by Congress in 1990 to facilitate calculating Medicaid rebates. The Budget Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA) requires that AMP be used to calculate the federal upper limit (FUL) for drugs that are paid through Medicaid. The FUL represents the maximum of federal matching funds that the federal government pays to state Medicaid programs for eligible generic and multisource drugs. With the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (health care reform) on March 23, 2010, the AMP was established as 175% of the ASP.

Typically, the reimbursement formula for a generic product is different than that for a brand product. Solesource or brand-name drugs are usually reimbursed based on AWP or WAC, whereas generic or multisource drugs are reimbursed based on a maximum allowable cost (MAC) schedule, which is usually based on the cost of the lowest available generic equivalent. Commercial insurance companies and Medicaid often use MAC lists for generic reimbursement; however, these lists can present a challenge to pharmacies because they may not be published and are widely variable from one insurance company to another.

Sample formulas include the following:

Sole-source drug reimbursement = AWP – 15% + $3.50 dispensing fee

Sole-source drug reimbursement = AWP – 15% + $3.50 dispensing fee

Multisource drug reimbursement = MAC + $3.50 dispensing fee

Multisource drug reimbursement = MAC + $3.50 dispensing fee

Here are some examples:

Sole source drug with an AWP of $100

Sole source reimbursement = $100 – $15 + $3.50 = $88.50

Multisource drug with a MAC of $50

Multisource reimbursement = $50 + $3.50 = $53.50

The dispensing fees are widely variable and typically range from $1.50 to $6.00 per prescription. This fee is somewhat unrelated to the actual cost of dispensing a prescription because the fee does not reflect the actual time spent by the pharmacist. The dispensing fee may differ for brand and generic prescriptions.

Some third-party payers may pay a higher dispensing fee for generic drugs or formulary products as an incentive to encourage utilization of preferred products.

Some third-party payers may pay a higher dispensing fee for generic drugs or formulary products as an incentive to encourage utilization of preferred products.

Payment for Drugs and Dispensing Services

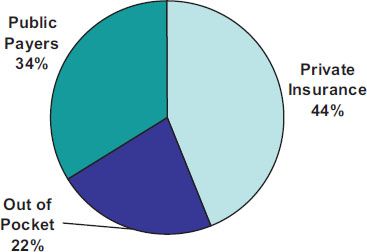

In 2008, $234 billion were spent on outpatient prescription drugs in the United States. Private insurance paid for 42% of this total, followed by public payers such as Medicare and Medicaid, which paid for 37%. Consumers paid the remaining 21% in the form of out-of-pocket payment for prescriptions or copayments (figure 20-1).3

Consumers (Self-Pay)

Although many patients have some form of prescription drug coverage, a significant number of Americans are uninsured or underinsured. Since the implementation of Medicare and Medicaid in the 1960s and the implementation of the Medicare Modernization Act in 2006, the percentage of patients who pay directly for prescription drugs has decreased. However, some patients who lack prescription drug coverage as a medical benefit may still pay directly. In these cases, reimbursement formulas are set by the pharmacy and are similar to those that have been described previously; however, the patient is fully responsible for the amount paid. The amount that is paid by a cash-paying customer is often referred to as the “usual and customary price” or the “cash price.” Many thirdparty contracts indicate that the amount to be paid for a prescription is based on a reimbursement formula (as previously explained) or the usual and customary price. The lower of the two prices is the amount usually paid.

Figure 20–1. Sources of payment for retail prescription drugs in 2008. Data from Kaiser Family Foundation.

Many drug companies offer certain free drugs through patient assistance programs (PAPs) to low-income patients who lack prescription drug coverage and meet certain criteria. The criteria for PAPs are widely variable and are determined by individual drug companies. In most cases, the products that are available free to the patient are proprietary drugs, and the patient is required to complete an application that determines eligibility. On approval, the drug company delivers a specified quantity of the drug (usually a 30to 90-day supply) to a licensed pharmacist or physician on the patient’s behalf.

Some companies also offer bulk replacement or institutional patient assistance programs (IPAPs). In the IPAP model, medications are provided to an institution (e.g., pharmacy or clinic) rather than to the individual patient. The institution has the obligation of verifying that each patient who receives medications meets the established criteria. In the IPAP model, pharmacies typically receive “replacement” product for medications that have already been dispensed.

RX for Success

Pharmacy technicians can play an important role in helping pharmacists identify and enroll eligible patients in Patient Assistance Programs.

Copay foundations or independent charity patient assistance programs are other resources that can be used to help patients who can’t afford to pay for prescriptions or copays. A list of resources for PAPs and various copay foundations is available at the end of this chapter.

The 340B drug pricing program is another option that can be utilized to assist patients who lack adequate prescription drug coverage. There are several types of facilities that qualify as “covered entities” for 340B pricing, including federal qualified health centers (FQHCs), disproportionate share hospitals (DSH), and state-owned AIDS drug assistance programs. Covered entities that are eligible to participate in the drug pricing program can offer drastically reduced drug prices to eligible patients.

The Office of Pharmacy Affairs, which is located within Health Resources and Services Administration, administers the 340B drug discount program.

Private Insurance

In 2008, 42% of prescription drugs were paid by private insurance.3 The most common purchasers of private insurance are employers, labor unions, trust funds, and professional associations. Additionally, individuals can purchase private insurance directly from an insurance company. Private insurance can be either managed care (based on a network of providers) or indemnity (nonnetwork-based coverage). Managed care is a type of private health insurance or health care organization that is based on networks of providers, such as pharmacies, doctors, and hospitals. The cost to the employee for managed care plans is typically lower than indemnity insurance, as long as the employee accesses providers within the contracted network. Indemnity insurance offers more choices of physicians and hospitals, but the employee’s out-of-pocket costs are higher than with managed care. With indemnity insurance, either the patient pays up front or the provider accepts payment after the services are rendered.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are organizations that administer pharmacy benefits for private or public third-party payers, also known as plan sponsors. These organizations may include managed care organizations, self-insured employers, insurance companies, labor unions, Medicaid and Medicare prescription drug plans, the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program, and other federal, state, and local government entities. Some of the major PBMs are CVS Caremark, Medco, Express Scripts, Walgreens Health Initiatives, and Wellpoint Pharmacy Management. About 95% of people who have prescription drug coverage receive their benefit from a PBM.5

Once a plan sponsor chooses a PBM to manage the pharmacy benefit, the sponsor pays the PBM a fee that is usually based on the number of beneficiaries (plan members and dependents) who are covered by the pharmacy benefit. The fee should cover the total cost of the pharmacy benefit (including all prescriptions) for the covered beneficiaries. In return for the fee paid by the plan sponsor, the PBM administers the pharmacy benefit under the direction of the sponsor. The PBM designs and manages the pharmacy benefit so that the cost of prescriptions dispensed does not exceed the amount of money paid to the PBM by the sponsor. For example, PBMs and their sponsors develop formularies, negotiate discounts or rebates with pharmaceutical companies, set copays, communicate with providers and beneficiaries, keep track of all prescriptions dispensed, and pay network pharmacies for prescriptions dispensed that are covered by the pharmacy benefit.

The formulary is the cornerstone of any PBM activities. It is a specific list of drugs that is included with a given pharmacy benefit. The formulary usually includes both brand and generic drugs in most therapeutic categories. Brand-name drugs can be either preferred (designated by the PBM as the first-choice drugs) or nonpreferred. The PBM may charge different copays for different types of formulary drugs. For example, a typical copay for a generic drug is $10, for a preferred brand-name drug is $26, and for a nonpreferred brandname drugs is $46. These levels of copays are known as copay tiers.

The PBM can utilize administrative tools within the context of the formulary in order to optimize the clinical and economic performance of the pharmacy benefit. Some of the more common administrative tools are prior authorization, step therapy, and quantity limits.6 Prior authorization requires the prescriber to receive preapproval from the PBM in order for the drug to be covered by the benefit. The prescription is not paid for by the PBM until prior authorization has been given. Prior authorization is often used for newer drugs, such as those that have only been on the market for six months or less, so that the PBM can ensure that the drugs are being prescribed according to guidelines of the FDA and evaluate the impact of these new drugs on the formulary.

Step therapy requires use of a recognized first-line drug before a more complex or expensive second-line drug is used. Beneficiaries must try and fail with the firstline drug before a second-line drug can be covered by the benefit. For example, the PBM might require use of a generic antibiotic before newer, more complex, broad spectrum antibiotics are prescribed.

Quantity limits set upper limits of the amount of a drug that is covered by the benefit, or the total days of therapy. For example, the benefit may limit the duration of therapy with proton-pump inhibitors for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease to eight weeks. In the best interest of the patient, the physician or pharmacist may request an override of any of the restrictions the PBM places on therapy. If the physician or pharmacist requests an override and it is approved, the desired therapy is covered by the pharmacy benefit for that patient. Or the physician can simply prescribe another equivalent medication for the patient that does not have utilization restrictions.

For PBMs, administering the pharmacy benefit is a constant balancing act of managing costs and providing quality service and value to their sponsors and beneficiaries. Many PBMs try to achieve this balance by offering mail service for prescriptions, whereby beneficiaries can get up to a 90-day supply of medication through the mail for a reduced copayment. Some pharmacy benefit plans require beneficiaries to use the PBM mail service for certain prescription refills. Another way that PBMs try to better serve their customers and manage costs is to offer specialty services for beneficiaries who require high-cost drugs, such as the newer biotechnology drugs that patients inject themselves (e.g., some medications for multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis). These specialty services may include special delivery of the medication to the beneficiary’s home at no charge, free nursing visits to help train the patient to inject the medication, a 24-hour hotline for the beneficiary to ask a pharmacist questions about the medication, and prior authorization assistance. Overall, PBMs provide a complex and valuable service for the health care system and assist plan sponsors in administering the pharmacy benefit to millions of beneficiaries.

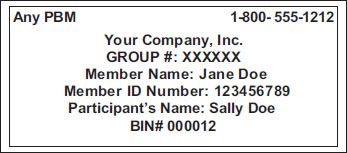

Processing Private Third-Party Prescriptions. Patients with a prescription drug benefit should have a prescription identification (ID) card. The information on the prescription ID card is necessary in order to submit a claim to the PBM. Figure 20-2 is an example of a typical prescription ID card.

The card identifies the PBM (Any PBM) or drug benefit provider. It shows a telephone number for the PBM customer service department. The employer may be identified (Your Company, Inc.), followed by the Member Name (Jane Doe) and Member ID Number (12345678). If the beneficiary is different from the plan member, such as a dependent child, the Participant’s Name may be listed. Finally, the BIN # (000012) is the bank identification number, which is also needed to submit the claim. It references the claims processor or PBM.

Figure 20–2. Example of a typical prescription ID card.

Once the technician enters information in the pharmacy computer from the prescription ID card and the prescription, the PBM either accepts or rejects the claim. If the claim is rejected, the PBM responds with a message, commonly known as a rejection code. Such codes are standard across all prescription benefit plans and may include “Missing or Invalid Patient ID,” “Prior authorization required,” “Pharmacy not contracted with plan on date of service,” “Refill too soon,” or “Missing or invalid quantity prescribed.”7 The technician must assess the meaning of the rejection code and respond accordingly. The resolution may be simple, such as checking the patient ID and making sure it was entered correctly. Or the pharmacist or physician may need to take further action (such as obtaining prior authorization) in order for the claim to be processed. If the issue can’t be resolved or if the rejection code is unclear, the technician may need to call the PBM customer service, which is usually listed on the prescription ID card.

Public Payers

In 2008, 37% of prescription drugs were paid for by public payers. Medicare is the largest public payer, accounting for 60% of prescription charges in 2008, followed by Medicaid at 22%, and other public payers, such as the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, and the Indian Health Service at 12%.8

Medicare. Medicare is the federal health program for the elderly, disabled, and people with end-stage renal disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), otherwise known as Lou Gehrig disease.9 Most people automatically qualify for Medicare once they turn 65 years of age and are eligible for Social Security payments, and if they or their spouse have made payroll tax contributions to Medicare for a total of 10 years or 40 quarters. There are four parts to Medicare:

Part A (hospital insurance)

Part A (hospital insurance)

Part B (medical insurance)

Part B (medical insurance)

Part C (Medicare Advantage plans)

Part C (Medicare Advantage plans)

Part D (prescription drug coverage)

Part D (prescription drug coverage)

Medicare Part A. Medicare Part A helps cover inpatient care (hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, hospice care, and some home health care). For most people, Part A coverage is pre-paid through payroll taxes. Individuals not entitled to premium-free Part A may purchase coverage by paying a monthly premium. Medicare Part A coverage involves a deductible and a benefit period of 60 days. A deductible is an out-of-pocket amount that must be paid before insurance coverage begins. Full Medicare coverage applies for the first 60 days; thereafter, the beneficiary is responsible for coinsurance, which is a fixed percentage charge for a service.10–12

Part A claims are processed by a fiscal intermediary, and the diagnosis-related group (DRG) is the basis for reimbursement. A fiscal intermediary acts as an agent for the federal government that processes and pays Medicare claims. A diagnosis-related group is a set rate paid for an inpatient procedure based on cost and intensity. It is important to understand that drugs provided during an inpatient stay are not separately reimbursed; they are included in the DRG payment.

Medicare Part B. Medicare Part B is optional medical insurance for outpatient physician and hospital services, clinical laboratory services, and durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics, and supplies (DMEPOS). Part B coverage involves paying a monthly premium, an annual deductible, and coinsurance. Because Part B coverage is optional, beneficiaries are required to enroll actively in order to receive benefits, and they may incur higher premiums if enrollment is delayed. Part B may cover medical services that Part A does not cover, such as some home health care and physical and/or occupational therapy services.

Medicare Part B pays for medically necessary services and supplies and covers some preventative services, such as pneumococcal vaccines and cancer screenings (cervical, breast, colorectal, and prostate). Medicare Part B benefit categories include specific drug products, such as immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., mycophenolate, cyclosporine) used for transplant patients, erythropoietin stimulating agents (e.g., epoetin, darbepoetin) for home dialysis patients, oral anticancer drugs, and oral antiemetic drugs (in place of intravenous antiemetics).

Medicare does not always pay 100% for Part B covered items. Each Medicare covered item is assigned to a payment category, which determines the amount Medicare pays. Most often, Medicare pays a percentage (e.g., 80%) of the approved amount after the patient’s deductible has been met, and the patient is responsible for paying the remaining portion (e.g., 20%), known as coinsurance. Individuals with Part B coverage are responsible for the premium, deductible, copayment, and coinsurance amounts.12

If the patient has a secondary insurance, the copayments or coinsurance may be submitted to the secondary insurer. Part B claims are processed by a local Medicare carrier, and DMEPOS items are processed by DME Medicare administrative contractors (DME MACs). If an assigned claim is not filed within one year, Medicare reduces the allowed amount by 10% for payable claims.12

Medicare Part C. Medicare Part C is the Medicare Advantage Plan, which combines Part A and B coverage. Under this plan, benefits are provided by Medicare-approved private insurance companies. These private fee-for-service and managed care plans often include prescription drug benefits, called Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug plans or MAPDs; as such, Part C beneficiaries should not enroll in a Part D prescription drug plan. There are five types of Part C plans: health maintenance organizations (HMOs), preferred provider organizations (PPOs), medical savings account plans, private fee-for-service plans, and Medicare special needs plans.

Medicare Part C beneficiaries are required to pay premiums, deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance for services. Medicare Advantage Plans charge one combined premium for Part A and B benefits and prescription drug coverage (if included in the plan).

Medicare Part D. Medicare Part D is a federal prescription drug program that is paid for by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and by individual premiums. It was enacted as part of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003. Medicare Part D offers a voluntary insurance benefit for outpatient prescription drugs.

Everyone who is eligible for Medicare Part A or Part B is also eligible for Medicare Part D. Individuals must enroll in Medicare Part D by joining a Medicare prescription drug plan or a Medicare Advantage plan that includes coverage for prescription drugs.

Everyone who is eligible for Medicare Part A or Part B is also eligible for Medicare Part D. Individuals must enroll in Medicare Part D by joining a Medicare prescription drug plan or a Medicare Advantage plan that includes coverage for prescription drugs.