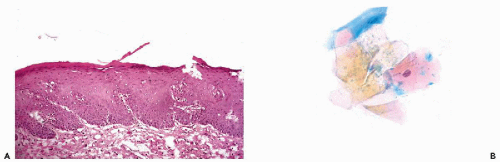

normally above the enlarged basal zone; hence, basal hyperplasia of squamous epithelium cannot be detected in smears unless there is a total loss of superficial cell layers or if the sample is obtained by energetic brushing. The etiology of the process is unknown but there is no evidence that it is related to cancer.

cells that are difficult to classify and may be the subject of a dispute as to their exact significance.

or may be very extensive and involve the surface epithelium and the glands. Squamous metaplasia is a normal, physiological event during maturation of the female genital tract, notably in the epithelium of the transformation zone, as discussed in Chapter 8.

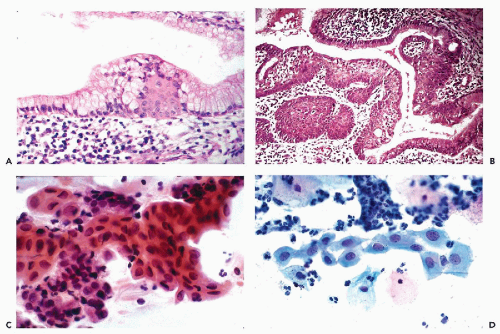

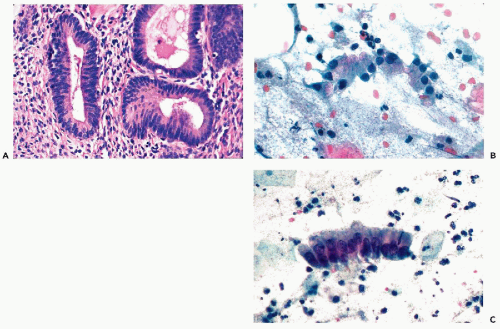

Figure 10-3 Basal cell hyperplasia of endocervix. A cluster of relatively small polygonal cells attached to well-differentiated endocervical cells. |

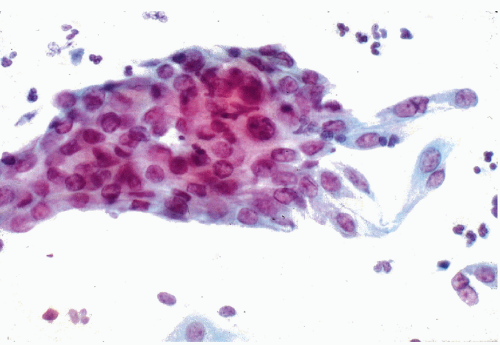

epithelium that may be either mature, resembling the squamous epithelium of the vagina, or immature, composed of smaller squamous cells of intermediate or parabasal type (Fig. 10-4B). The term immature, as used here, should not be confused with a malignant process. Various stages of transition between normal endocervical epithelium and mature metaplastic squamous epithelium may be observed. By special stains, mucus may nearly always be demonstrated in the cytoplasm of the metaplastic cells, indicating close relationship to the endocervical epithelium. Squamous metaplasia may replace the endocervical mucosa lining the endocervical canal or endocervical glands. Squamous metaplasia of endocervical glands may be discrete and focal, or diffuse. In extreme cases, one or several glands may be filled with squamous epithelium. If the metaplastic squamous epithelium is immature, the finding may mimic a neoplastic process, as discussed below under atypical metaplasia.

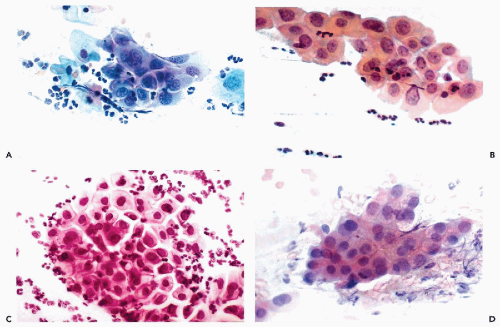

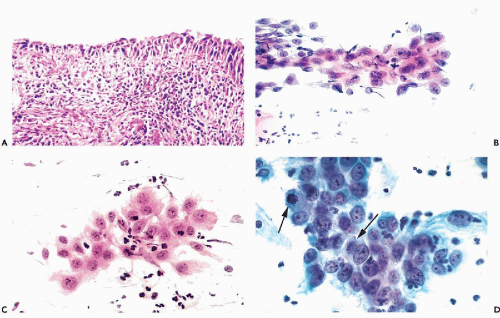

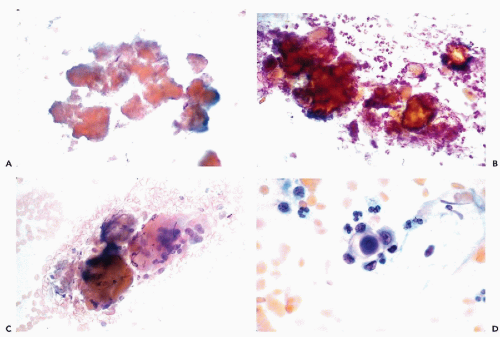

are subsequently shown to harbor precancerous lesions or even cancer of either squamous or endocervical type. Therefore, patients with marked nuclear changes (Fig. 10-5B-D) should have the benefit of a close, careful follow-up, including colposcopy and biopsies of cervix, particularly if, in addition to cell clusters, single abnormal cells are present in the smear. The role of testing for human papillomavirus in such cases is discussed in Chapter 11.

cases of endocervical carcinoma in situ of tubal type and stressed that the mere presence of ciliated epithelium does not guarantee that the lesion is benign.

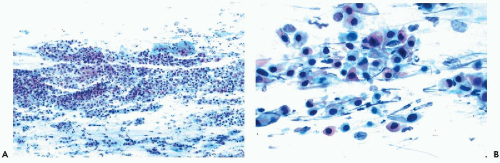

abnormalities consisted of nuclear hyperchromasia, large cohesive cell clusters, and the presence of mitotic activity and of necrotic cells, described as “apoptosis.” Similar observations were reported by Hanau et al (1997). The histologic findings in these cases disclosed various degrees of atypia in the glands which, in two cases, was “severe.” Although Mulvany and Surtees did not classify the abnormalities as malignant, it is well known that endometrioid carcinomas may originate in the endometriotic glands (Koss, 1963; Brooks and Wheeler, 1977; Mostoufizadeh and Scully, 1980). These abnormalities must be considered in the differential diagnosis of endocervical adenocarcinoma.

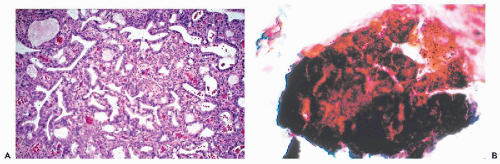

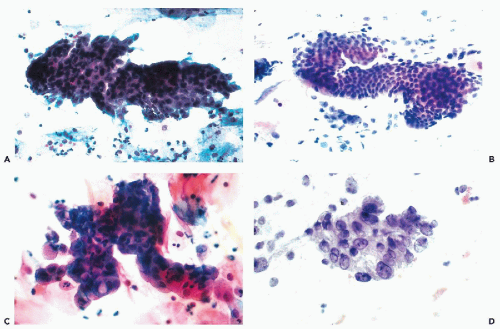

(Fig. 10-7B). In order to secure such clusters, a very energetic brushing of the endocervix is required. In our experience, there are no specific cytologic abnormalities that would allow a reproducible recognition of microglandular hyperplasia. Some of the findings described are most likely artifacts caused by endocervical brushings (see below). However, some observers reported marked cytologic abnormalities associated with microglandular hyperplasia (Valente et al, 1994; Selvaggi and Haefner, 1997; Selvaggi, 2000). It is our judgment that, in such cases, the microglandular hyperplasia is an incidental biopsy finding. There is excellent evidence that the presence of microglandular hyperplasia does not rule out the presence of precancerous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix, as first pointed out by Nichols and Fidler (1971), or, for that matter, one of the rare cervical or endometrial adenocarcinomas mimicking microglandular hyperplasia (Young and Scully, 1992). Thus, the presence of atypical cells in smears calls for a careful investigation of the uterine cervix by methods discussed in Chapters 11 and 12, regardless whether or not microglandular hyperplasia is present.

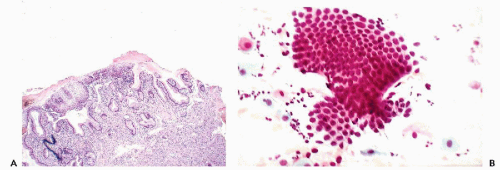

of the ectropion. Direct cervical smears contain only fragments of benign endocervical tissue and single columnar endocervical cells (Fig. 10-8B). Because the delicate epithelium lining the area is readily damaged during the process of obtaining smears, fresh blood is often present in the cytologic specimen. If a portion or all of the everted endocervical mucosa has undergone squamous metaplasia, squamous cells of varying degrees of maturity will appear in smears. The cytologic picture is vastly different from inflammatory or neoplastic lesions that may also occur in this part of the cervix, as described below and in Chapter 11. The eversion requires no treatment because, with the passage of time, it will undergo squamous metaplasia.

or florid squamous metaplasia of the endocervical epithelium.

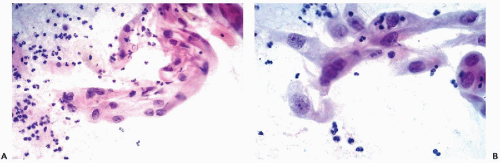

Figure 10-10 Repair reaction caused by an endocervical polyp. A,B. Marked abnormalities of metaplastic squamous cells with very large nuclei and bizarre cell shapes. |

the screening and evaluation of smears from patients wearing IUDs must be thorough and careful, and any abnormalities that cannot be clearly attributed to the device itself should be further evaluated and investigated.

lesion to occur in the form of tightly knit clusters of endocervical cells, without some ancillary evidence of disease, as discussed in the appropriate chapters.

Bacterial agents | |||

Cocci and coccoid bacteria | |||

Gram-positive cocci: species of Streptococcus and Staphylococcus | |||

Gram-negative cocci: Gonococcus | |||

Gardnerella vaginalis (Haemophilus vaginale or vaginalis) | |||

Diphtheroids | |||

Calymmatobacterium granulomatis Donovan (granuloma inguinale) | |||

Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma | |||

Chlamydia trachomatis | |||

Acid-fast organisms: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium | |||

Actinomyces | |||

Spirochaeta pallida (syphilis) | |||

Organisms that are normally saprophytic but may be associated with infections: | |||

Lactobacillus (Döderlein bacillus) and Leptothrix | |||

Other uncommon bacterial agents | |||

Fungal agents | |||

Candida species: C. albicans (monilia), C. glabrata (Torulopsis glabrata) | |||

Aspergillus species | |||

Coccidioidomycosis | |||

Paracoccidioidomycosis | |||

Cryptococcus species | |||

Blastomyces | |||

Viral agents | |||

Herpesvirus types I, II, VIII | |||

Cytomegalovirus | |||

Human polyomavirus | |||

Measles | |||

Adenovirus | |||

Molluscum contagiosum (vulva) | |||

Human papillomavirus, various types (see Chap. 11) | |||

Other rare viruses | |||

Parasitic infections and infestations | |||

Protozoa | |||

Trichomonas vaginalis | |||

Entamoeba histolytica | |||

Entamoeba gingivalis | |||

Balantidium coli | |||

Helminths (worms) | |||

Schistosoma haematobium, S. mansoni, S. japonicum | |||

Filariae | |||

Intestinal worms | |||

Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) | |||

Trichuris trichiura (whipworm) | |||

Teniae (flat worms) | |||

T. solium (intermediate host: swine) | |||

T. saginata (intermediate host: cattle) | |||

T. echinococcus (intermediate host: dog) | |||

Other uncommon parasites | |||

Trypanosomiasis | |||

Direct invasion of the genital tract by pathogens, often sexually transmitted

Spread of an infectious process from an adjacent organ

Blood-borne infections

which enter the area of injury. The macrophages are activated to phagocytize the debris and eliminate the damages. In some parasitic infestations, eosinophilic leukocytes may play a key role.

The injurious agent is eliminated, the inflammatory process is contained and healing commences, heralded by activation of stromal fibroblasts. The fibroblasts will provide the collagen necessary to replace the necrotic, injured tissue, resulting in the formation of a scar.

The acute inflammatory process continues with resulting increased necrosis and formation of purulent exudate or pus. Pus is a semiliquid mixture of blood serum, necrotic neutrophiles, macrophages and debris derived from the injured tissue. Accumulation of pus within a limited area of tissue results in an abscess that may be contained within a connective tissue capsule

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree