An anal fissure is a linear ulcer in the squamous epithelium of the anal canal located just distal to the dentate line. The French surgeon, Joseph-Claude-Anthelme Recamier (1774–1852), has been widely credited for having first described this pathology in the 1820s and subsequently went on to describe the technique of anal dilatation for treating this condition [1].

Anal fissures occur in both sexes equally, commonly affecting young and otherwise healthy individuals. However, the true incidence is likely to be higher, due to the combination of many people not seeking medical attention and with many others achieving resolution without intervention, particularly in the case of superficial anal fissures. Nonetheless, the predominant symptom of pain is often distressing enough to compel patients to seek medical attention, making anal fissures one of the most common anorectal pathologies treated by the colorectal surgeon, accounting for between 6.2 and 15 % of visits to colorectal clinics [2–6].

Sir Alan Parks once wrote that ‘if a patient complains of anal pain, the chances are that he has a fissure’ [7]. The pain is typically excruciating and has been described as the ‘passing of broken glass’, only to be followed by a burning pain that can persist for many hours afterwards. Goligher in turn described this lesion as causing ‘an amount of suffering out of proportion to the size of the lesion’ [8]. Not surprisingly, it had been shown that the pain associated with an anal fissure can result in a significant deterioration in the quality of life of affected patients [9]. There are often other accompanying symptoms such as the passing of bright red blood as well as anal pruritus. The fissure should be visualised by parting the buttocks and anal verge only, as this is often impeded by anal pain. The fissure can almost always be seen and the diagnosis secured. Digital or proctoscopic examination, however, is often impossible due to extreme discomfort and should not be attempted in such situation anyway. There is no immediate reason to perform an examination under general anaesthesia to confirm the diagnosis under normal circumstances especially in a young and otherwise healthy person. Table 15.1 gives the common symptoms reported in studies on anal fissures.

Table 15.1

Common symptoms in patients with anal fissure

S/N | Study | Year | Symptoms | No of patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. | Jensen SL | 1986 (BMJ) | Post-defaecatory pain | 96 (100) |

Bleeding | 74 (77.1) | |||

Constipation | 65 (67.7) | |||

Pruritus | 36 (37.5) | |||

Soiling | 17 (17.7) | |||

Diarrhoea | 8 (8.3) | |||

2. | Maria G | 1998 (NEJM) | Post-defaecatory pain | 30 (100) |

Nocturnal pain | 4 (13.3) | |||

3. | Maria G | 1998 (Annals) | Post-defaecatory pain | 57 (100) |

Nocturnal pain | 16 (28.1) | |||

4. | Brisinda G | 1999 (NEJM) | Post-defaecatory pain | 50 (100) |

Nocturnal pain | 9 (18) | |||

Bleeding | 9 (18) | |||

5. | Kocher HM | 2002 (BJS) | Post-defaecatory pain | 60 (100) |

Bleeding | 46 (76.7) | |||

Pruritus | 44 (73.3) | |||

Discharge | 25 (41.7) | |||

6. | Arroyo A | 2004 (JACS) | Post-defaecatory pain | 74 (92.5) |

Bleeding | 66 (73.3) | |||

Constipation | 53 (66.3) | |||

Pruritus | 43 (53.8) | |||

7. | Arroyo A | 2005 (Am J Surg) | Post-defaecatory pain | 73 (91.3) |

Bleeding | 67 (83.8) | |||

Constipation | 55 (68.8) | |||

Pruritus | 43 (53.8) | |||

8. | Ho KS | 2005 (BJS) | Post-defaecatory pain | 94 (71.2) |

Bleeding | 69 (52.3) | |||

Pruritus | 33 (25) | |||

9. | Brisinda G | 2007 (BJS) | Post-defaecatory pain | 100 (100) |

Nocturnal pain | 16 (16) | |||

Bleeding | 23 (23) | |||

10. | Renzi A | 2008 (DCR) | Post-defaecatory pain | 49 (100) |

Bleeding | 49 (100) |

Classification of Fissures

Superficial vs Deep

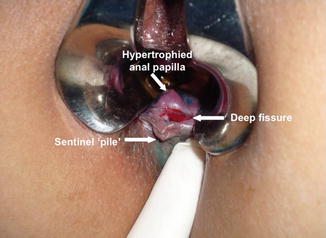

Anal fissures are classically and usually classified into acute or chronic fissures according to well-established morphological features. The length of time of symptoms ironically is usually irrelevant to whether a fissure is acute or chronic. These names are therefore inaccurate and misleading. We suggest a complete name change so as not to perpetuate this mistake. As such, we prefer to call ‘acute fissures’ superficial fissures and ‘chronic anal fissures’ deep anal fissures. Superficial fissures, as the name implies, involve only the superficial mucocutaneous layers of the anal canal. They may have symptoms of severe pain and bleeding, presenting as a superficial separation of the anoderm, usually linear or elliptical-shaped in appearance with sharply demarcated edges (Fig. 15.1). The vast majority of superficial fissures will heal spontaneously within days or at most up to 6 weeks of appropriate conservative treatment [10]. In contrast, deep fissures persist often and either tend not to heal without intervention or recur regularly.

Fig. 15.1

Superficial and deep anal fissure

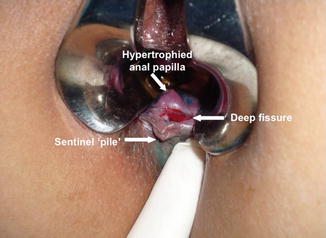

Deep anal fissures are recognised by most authors by the morphological features of a deep and wide pear-shaped ulcer often with visible fibres of the internal anal sphincter and minimal granulation tissue at its base. Other features of a deep anal fissure include the distinctive triad of indurated ulcer edges, a distal skin tag (sentinel pile) and a proximal hypertrophied anal papilla [4, 11] (Fig. 15.2). The latter however is not universal. A standardised definition should be established to facilitate the uniformity of future trials and to explain the widely differing healing rates of the various treatments in the literature. Lindsey et al. [11] have proposed a definition based on the combination of chronology and morphology by describing a deep anal fissure as ‘the presence of visible transverse internal anal sphincter fibres at the base of an anal fissure of duration not less than 6 weeks’. However, we have often observed such features presenting within a week or less of painful defaecation and/or bleeding, and therefore, we stress that duration is irrelevant and again urge a more appropriate name for these sorts of fissures to be deep anal fissures. In addition, deep fissures may be further defined by the presence or absence of the hypertrophied anal papilla. Our own observations lead us to postulate that a superficial fissure is a shallow separation of the anoderm that does not reach the internal sphincter muscle. This sort of fissure heals readily without too much fuss. Most of us would have one time or the other have had this sort of anal pain but the majority of these heal spontaneously. Deep anal fissures however may result from prolongation or repeat of the forces causing superficial anal fissures, or else, they may occur de novo as a result of a deep tearing right from the start and may therefore appear almost immediately. An example of such a fissure would be a deep fissure appearing at the site of a haemorrhoidectomy wound.

Fig. 15.2

Deep anal fissure with hypertrophied anal papilla and sentinel pile

Typical vs Atypical

Fissures can also be classified based on their location and aetiology. Typical fissures are usually single and situated in the posterior midline (6 o’clock position), with 2.5–13 % of fissures occurring in the anterior midline (12 o’clock position) in up to 10 % of women compared to 1 % of men [4, 8, 12]. Occasionally, patients can also present with fissures in both these locations concurrently. Multiple fissures occurring in unusual locations should raise suspicion of an atypical aetiology.

Atypical or secondary fissures are usually associated with some underlying diseases, most notably inflammatory bowel diseases, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, anal cancer, syphilis, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis and radiotherapy, or may even point to possible sexual abuse and anal-receptive intercourse. Such fissures tend to be accompanied by an unusual history or clinical features such as hypotonic anal sphincters, large size, irregularity as well as being multiple or sited at unusual lateral locations or both [4, 13, 14]. It is therefore essential to exclude more proximal bowel or systemic pathology in the presence of atypical features on clinical examination, which generally requires an examination under anaesthesia and even biopsy to establish a conclusive diagnosis. In addition, the persistence of fissures following surgical sphincterotomy should also raise one’s suspicion of a possible secondary aetiology.

The incidence of deep anal fissures in patients with Crohn’s disease has been reported to be approximately 26 % and is sometimes the only manifestation of the disease [15, 16]. They tend to occur in atypical locations, are often deeper and can potentially result in significant deformity. In addition, they are commonly associated with other anorectal pathology, especially fistula. Lewis et al. reported that 5 of 21 patients with persistent fissures after surgical sphincterotomy were found to have Crohn’s disease and the occurrence of fissures has been postulated to be due to microvascular ischaemia.

The anorectum is one of the sites commonly afflicted by HIV infection, which may manifest as several lesions including anal fissures [17–21]. The incidence of anal fissures in HIV patients is reported to vary between 7 and 32 %, with about 5 % of patients presenting without foreknowledge of the diagnosis of HIV infection [21, 22]. Anal fissures in such patients are usually located more proximally, often extending above the dentate line and located at atypical lateral sites [23–25]. These fissures are often associated with other anorectal lesions, such as ulcerations, perianal abscesses and fistulae, with concurrent infections variously attributed to Cryptococcus sp., cytomegalovirus (CMV), Chlamydia sp., herpes simplex virus (HSV), Treponema pallidum and Haemophilus ducreyi [20, 26–30]. It should be noted that anal fissures in HIV patients may be associated with hypotonicity of the anal sphincter, as a result of persistent diarrhoea and their anal-receptive sexual practices [21, 25]. As such, surgical intervention is not routinely recommended as they are commonly associated with impaired anal sphincter function.

Anorectal tuberculosis is exceedingly rare, occurring in approximately 0.7 % of patients infected with this granulomatous disease. Adding to the diagnostic challenge is the notoriously low yield of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) from the lesion [23, 29, 30]. The ulcerated form of anal TB typically presents as a superficial, non-indurated lesion, with a hemorrhagic necrotic base that is granular and covered with thick mucopurulent secretions. The lesion may be very painful or the patient may have few symptoms [31]. The tuberculin skin test remains a valuable guide because it is positive in 75 % of cases. Patients with a tuberculous fissure will usually have symptoms of the disease in other systems, especially in the chest and other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, either as an extension of the original lesion or due to its spread via the lymphatics [32]. In addition, tuberculosis can be a complicating infection of HIV-positive patients, with the incidence and severity of ano-perianal tuberculosis increasing due to the increasing incidence of HIV infection [33, 34]. The diagnosis may be suspected from the persistence of anal fissure despite conventional therapy, and confirmation is by tissue biopsy.

Other causes of secondary anal fissures include malignant lesions such as various forms of leukaemia, lymphoma as well as squamous and basal cell carcinomas, malignant melanoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma and adenocarcinoma of the anorectum, all of which may be diagnosed based on histology obtained from biopsies of the lesion [25, 30].

High Pressure vs Low Pressure

Since the seminal lecture by Brodie BC in 1835 regarding the existence of elevated anal tone in patients with anal fissures, anal hypertonicity had remained a leading hypothesis and had helped to shape much of the research and development of treatment for this disease entity [35]. Table 15.2 shows the distribution of anal canal resting pressures in studies of patients with anal fissures before and after treatment.

Table 15.2

Anal canal pressures in patients with deep anal fissures

Study | Year | No. of patients | Treatment | Mean anal resting pressure ± SD (mmHg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Before | After | ||||

Olsen J | 1987 (IJCD) | 10 | Lateral anal sphincterotomy vs anal dilatation | 80 ± 10 | 68 ± 5 |

10 | 84 ± 4 | 55 ± 13a | |||

Lund JN | 1997 (Lancet) | 38 | 0.2 % GTN ointment vs placebo | 85.2 ± 23.2 | 55.8 ± 22.1a |

39 | 86.8 ± 32.8 | 82 ± 23.5 | |||

Maria G | 1998 (NEJM) | 15 | 20U botulinum toxin vs 0.4 ml saline | 109 ± 8 | 81 ± 8a |

15 | 102 ± 6 | 97 ± 7 | |||

Maria G | 1998 (Annals) | 23 | 15U botulinum toxin vs 20U botulinum toxin | 94 ± 35 | 79 ± 33 |

34 | 110 ± 30 | 79 ± 27a | |||

Brisinda G | 1999 (NEJM) | 25 | GTN ointment vs 20U botulinum toxin | 83.4 ± 15.0 | 71.9 ± 17a |

25 | 89.8 ± 21.2 | 64.2 ± 14.9a | |||

Arroyo A | 2004 (JACS) | 40 | Open lateral sphincterotomy vs closed lateral sphincterotomy | 109 ± 29 | 75 ± 17a |

40 | 119 ± 21 | 78 ± 20a | |||

Parellada C | 2004 (DCR) | 27 | 0.2 % GTN ointment vs lateral sphincterotomy | 58.8 ± 14.3 | 41.2 ± 18a |

27 | 52.9 ± 10.2 | 35.3 ± 7.4a | |||

Arroyo A | 2005 (Am J Surg) | 40 | Open lateral sphincterotomy vs 25U botulinum toxin | 109 ± 29 | 72 ± 17a |

40 | 114 ± 26 | 92 ± 26a | |||

Ho KS | 2005 (BJS) | 48 | Lateral sphincterotomy vs tailored sphincterotomy vs oral nifedipine | 53.1 ± 4.0 | 43.4 ± 4.0a |

43 | 66.7 ± 7.6 | 47.7 ± 3.4a | |||

41 | 44.9 ± 4.5 | 42.7 ± 6.8 | |||

Brisinda G | 2007 (BJS) | 50 | 20U botulinum toxin vs 0.2 % GTN ointment | 90.2 ± 19.7 | 70.2 ± 18.9a |

50 | 89.2 ± 21.0 | 72.6 ± 16.0a | |||

Renzi A | 2008 (DCR) | 24 | Pneumatic dilatation vs lateral sphincterotomy | 94.4 ± 11.3 | 65.6 ± 6.6a |

25 | 96 ± 12.1 | 63 ± 5.7a | |||

Nevertheless, debate still ensues regarding the consistency of this association, as anal fissures associated with normal or hypotonic sphincters (low-pressure fissures) have been reported in the postpartum period, in the elderly as well as in secondary fissures associated with underlying disease [14, 36, 37]. Bove and colleagues, in a study assessing anal pressure profiles of patients with deep anal fissure, revealed that 52.1 % of patients had mean resting anal pressures within the normal range (35–50 mmHg), with up to 5 % of patients (significantly older of mean age 56.5 ± 11.1 years) having a hypotonic anal canal [38]. These findings highlight the fact that sphincter hypertonicity is not universally present in patients with anal fissures and that treatment should not just be directed at decreasing anal canal pressures.

Considered the gold standard against which all treatments are compared, lateral internal sphincterotomy has been shown to effectively decrease resting anal pressure by up to 50 %, helping to improve anodermal blood flow and thereby possibly promoting fissure healing in patients with elevated sphincter pressures [39, 40]. However, lateral anal sphincterotomy had been shown to be associated with anal incontinence postoperatively, possibly as a result of overzealous sphincter division or due to the presence of undiagnosed sphincter injuries, with incontinence rates ranging from 3.3 to 16 % [41–48]. Several authors have shown encouraging results in their efforts to reduce incontinence rates by using a tailored approach to sphincterotomy guided by preoperative manometric findings [49, 50] as well as by limiting the extent of division to the fissure apex [51]. Consequently, it is easy to appreciate the disastrous consequences of an unnecessary sphincterotomy performed on a patient with normal or low sphincter pressures. In the latter groups of patients, a sphincter-preserving approach using anal advancement flaps offers a safer alternative, with several studies reporting favourable healing rates of more than 80 %, without the morbidity of postoperative incontinence [52–55].

Pathophysiology

Despite having been described more than 180 years ago, the precise mechanisms surrounding the pathophysiology of anal fissures had yet to be fully unravelled. However, with improvement in the understanding of the physiology of the anal sphincter, significant progress has been made in recent years and this has provided the rationale for current treatment modalities. An understanding of anal sphincter physiology is therefore an essential prelude to any discussion regarding the current treatment options for anal fissures.

Internal Anal Sphincter Physiology

The human internal anal sphincter (IAS) exists in a state of tonic contraction and its function is modulated by three main components, namely, intrinsic myogenic tone and the enteric and autonomic nervous systems, reflecting the sphincter specialisation of this muscle [56]. Basal tone of the IAS is primarily myogenic, which is modulated by neurohormonal substances such as alpha- and beta-adrenoreceptor agonists, as well as inhibitory neurotransmitters including nitric oxide (NO), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and carbon monoxide (CO) [57, 58].

Firstly, intrinsic myogenic tone is a spontaneous phenomenon that results from the contraction of smooth muscle cells within the IAS, mediated by the influx of calcium through L-type calcium channels [59]. There are also two groups of alpha (α) adrenoreceptors within the IAS; stimulation of α1-adrenoreceptors causes IAS contraction [60], whilst activation of α2-adrenoreceptors inhibits non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic (NANC) relaxation. Conversely, the stimulation of beta-adrenoreceptors inhibits sympathetic stimulation of the IAS [57]. Consequently, the dominant α-adrenoreceptor population in the IAS results in the tonic state of contraction.

The enteric nervous system is located in the Auerbach’s and Meissner’s plexuses in the wall of the gut and is responsible for peristalsis as well as local reflexes such as the rectoanal inhibitory reflex. These nerves are known to be NANC because neither guanethidine nor atropine blocks their activity, although the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin blocks their activity [61]. Activation of α2-adrenoreceptors in the myenteric inhibitory neurons presynaptically inhibits NANC relaxation. Relaxation is mediated through directly decreasing intracellular calcium concentration as well as increasing cyclic guanosine monophosphate and cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Potassium influx hyperpolarises the cell membrane and decreases calcium entry. In addition, inhibitory neurotransmitters, such as nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide, mediate NANC relaxation.

Nitric oxide is the major neurotransmitter mediating NANC relaxation of the IAS [57, 58], an action that is blocked by N-nitro-L-arginine (a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor) and enhanced by L-arginine (a nitric oxide precursor) [62]. The presence of nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-positive neurons in the rectal myenteric plexus and anal canal has been confirmed by immuno-histochemical studies, demonstrating that these neurons ramify throughout the IAS and lay in close proximity to smooth muscle cells [63]. In Hirschsprung’s disease, a condition in which the rectoanal inhibitory reflex is absent, nerves containing NOS are absent from the non-relaxing segment but present in the normal segment of gut [64].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree